Carotenoid Content of U.S. Foods: an Update of the Database

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Association Between Serum Concentration of Carotenoid and Visceral Fat

nutrients Article Association between Serum Concentration of Carotenoid and Visceral Fat Mai Matsumoto 1,*, Hiroyuki Suganuma 1 , Naoki Ozato 2,3 , Sunao Shimizu 1,4,5 , Mitsuhiro Katashima 2,3, Yoshihisa Katsuragi 2,3, Tatsuya Mikami 5, Ken Itoh 4,6 and Shigeyuki Nakaji 5,7 1 Innovation Division, KAGOME CO. LTD., 17 Nishitomiyama, Nasushiobara, Tochigi 329-2762, Japan; [email protected] (H.S.); [email protected] (S.S.) 2 Department of Active Life Promotion Sciences, Graduate School of Medicine, Hirosaki University, 5 Zaifu-cho, Hirosaki, Aomori 036-8562, Japan; [email protected] (N.O.); [email protected] (M.K.); [email protected] (Y.K.) 3 Health & Wellness Products Research Laboratories, Kao Corporation, Tokyo 131-8501, Japan 4 Department of Vegetable Life Science, Graduate School of Medicine, Hirosaki University, 5 Zaifu-cho, Hirosaki, Aomori 036-8562, Japan; [email protected] 5 Innovation Center for Health Promotion, Graduate School of Medicine, Hirosaki University, 5 Zaifu-cho, Hirosaki, Aomori 036-8562, Japan; [email protected] (T.M.); [email protected] (S.N.) 6 Department of Stress Response Science, Center for Advanced Medical Research, Graduate School of Medicine, Hirosaki University, 5 Zaifu-cho, Hirosaki, Aomori 036-8562, Japan 7 Department of Social Medicine, Graduate School of Medicine, Hirosaki University, 5 Zaifu-cho, Hirosaki, Aomori 036-8562, Japan * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +81-80-1581-1874 Abstract: Consumption of fruits and vegetables rich in carotenoids has been widely reported to prevent cardiovascular diseases. However, the relationship between serum carotenoid concentrations Citation: Matsumoto, M.; Suganuma, and visceral fat area (VFA), which is considered a better predictor of cardiovascular diseases than H.; Ozato, N.; Shimizu, S.; Katashima, the body-mass index (BMI) and waist circumference, remains unclear. -

Genetics and Molecular Biology of Carotenoid Pigment Biosynthesis

SERIAL REVIEW CAROTENOIDS 2 Genetics and molecular biology of carotenoid pigment biosynthesis GREGORY A. ARMSTRONG,’1 AND JOHN E. HEARSTt 5frtitute for Plant Sciences, Plant Genetics, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, CH-8092 Zurich, Switzerland; and tDePai.tment of Chemistry, University of California, and Structural Biology Division, Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory, Berkeley, California 94720, USA The two major functions of carotenoids in photosyn- carotenoid biosynthesis from a molecular genetic thetic microorganisms and plants are the absorption of standpoint.-Armstrong, G. A., Hearst, J. E. Genet- energy for use in photosynthesis and the protection of ics and molecular biology of carotenoid pigment chlorophyll from photodamage. The synthesis of vari- biosynthesis. F14SEBJ. 10, 228-237 (1996) ous carotenoids, therefore, is a crucial metabolic proc- ess underlying these functions. In this second review, Key Words: phytoene lycopene cyclization cyclic xanthophylLs the nature of these biosynthetic pathways is discussed xanlhophyll glycosides’ 3-carotene provitamin A in detail. In their elucidation, molecular biological techniques as well as conventional enzymology have CAROTENOIDS REPRESENT ONE OF THE most fascinating, played key roles. The reasons for some of the ci.s-t Tans abundant, and widely distributed classes of natural pig- isomerizations in the pathway are obscure, however, ments. Photosynthetic organisms from anoxygenic photo- and much still needs to be learned about the regula- synthetic bacteria through cyanobacteria, algae, and tion of carotenoid biosynthesis. Recent important find- higher plants, as well as numerous nonphotosynthetic ings, as summarized in this review, have laid the bacteria and fungi, produce carotenoids (1). Among groundwork for such studies. higher plants, these pigments advertise themselves in flowers, fruits, and storage roots exemplified by the yel- -James Olson, Coordinating Editor low, orange, and red pigments of daffodils, carrots and to- matoes, respectively. -

Meet Lycopene Prostate Cancer Is One of the Leading Causes of Cancer Death Among Men in the United States

UCLA Nutrition Noteworthy Title Lycopene and Mr. Prostate: Best Friends Forever Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5ks510rw Journal Nutrition Noteworthy, 5(1) Author Simzar, Soheil Publication Date 2002 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Meet Lycopene Prostate cancer is one of the leading causes of cancer death among men in the United States. Dietary factors are considered an important risk factor for the development of prostate cancer in addition to age, genetic predisposition, environmental factors, and other lifestyle factors such as smoking. Recent studies have indicated that there is a direct correlation between the occurrence of prostate cancer and the consumption of tomatoes and tomato-based products. Lycopene, one of over 600 carotenoids, is one of the main carotenoids found in human plasma and it is responsible for the red pigment found in tomatoes and other foods such as watermelons and red grapefruits. It has been shown to be a very potent antioxidant, with oxygen-quenching ability greater than any other carotenoid. Recent research has indicated that its antioxidant effects help lower the risk of heart disease, atherosclerosis, and different types of cancer-especially prostate cancer. Lycopene's Characteristics Lycopene is on of approximately 600 known carotenoids. Carotenoids are red, yellow, and orange pigments which are widely distributed in nature and are especially abundant in yellow- orange fruits and vegetables and dark green, leafy vegetables. They absorb light in the 400- 500nm region which gives them a red/yellow color. Only green plants and certain microorganisms such as fungi and algae can synthesize these pigments. -

Dietary Factors That Affect Carotenoid Bioavailability' Van Karin H

Dietaryfactor stha taffec t carotenoid bioavailability KarinH .va n hetHo f Promotoren: Dr. J.G.A.J. Hautvast Hoogleraar ind e leer van devoedin g en gezondheid, Landbouwuniversiteit Wageningen Dr. C.E. West Universitair hoofddocent aan de afdeling Humane Voeding en Epidemiologie, Departement Levensmiddelentechnologiee n Voedingswetenschappen, Landbouwuniversiteit Wageningen Visiting Professor of International Nutrition, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta GA, USA Co-promotor: Dr. Ir.J.A . Weststrate Unilever Research Vlaardingen /J r'. Stellingen behorend bij het proefschrift 'Dietary factors that affect carotenoid bioavailability' van Karin H. van het Hof. Wageningen,4 jun i 1999. 1. "Natuurlijk" wordt vaak ten onrechte verward met gezond; wat betreft de biobeschikbaarheid van carotenoTden zijn juist de "onnatuurlijke" en technologisch bewerkte bronnen beter (ditproefschrift). 2. Optimalisatie van de biobeschikbaarheid van carotenoTden is geen geldig excuus voor eenvetrijk e maaltijd (ditproefschrift). 3. Homogenisatie verbetert de biobeschikbaarheid van carotenoTden uit groenten. De Hollandse stamppot isdaaro mz o slecht nog niet (ditproefschrift). 4. Een beperking in de aanwezigheid van gevalideerde biomarkers en gevoelige analysemethoden is een limiterende factor voor de vooruitgang in de voedingswetenschap. 5. Het gebruik van functional foods noopt tot een verdergaande individualisering van het eetgedrag. 6. Zolang een meerderheid van de vrouwen valt op mannen die ouder en minstens even intelligent zijn alszijzelf , vindt emancipatie aan deto p van organisaties geendoorgang . 7. Voor sommige mensen veroorzaakt de stiptheid van de Nederlandse Spoorwegen meerstres s danzij nvertragingen . OM'V ?0' , Dietaryfactor stha t affect carotenoid bioavailability Katharina Henrietteva n hetHo f Proefschrift ter verkrijging van degraa dva n doctor op gezag van de rector magnificus, vand e Landbouwuniversiteit Wageningen, dr. -

Enhanced Lycopene Production in Escherichia Coli by Expression of Two MEP Pathway Enzymes from Vibrio Sp

catalysts Article Enhanced Lycopene Production in Escherichia coli by Expression of Two MEP Pathway Enzymes from Vibrio sp. Dhg 1, 1, 1 1, Min Jae Kim y, Myung Hyun Noh y , Sunghwa Woo , Hyun Gyu Lim * and Gyoo Yeol Jung 1,2,* 1 Department of Chemical Engineering, Pohang University of Science and Technology, 77 Cheongam-Ro, Nam-Gu, Pohang, Gyeongbuk 37673, Korea; [email protected] (M.J.K.); [email protected] (M.H.N.); [email protected] (S.W.) 2 School of Interdisciplinary Bioscience and Bioengineering, Pohang University of Science and Technology, 77 Cheongam-Ro, Nam-Gu, Pohang, Gyeongbuk 37673, Korea * Correspondence: [email protected] (H.G.L.); [email protected] (G.Y.J.); Tel.: +82-54-279-2391 (G.Y.J.) These authors contributed equally to this work. y Received: 28 October 2019; Accepted: 26 November 2019; Published: 29 November 2019 Abstract: Microbial production is a promising method that can overcome major limitations in conventional methods of lycopene production, such as low yields and variations in product quality. Significant efforts have been made to improve lycopene production by engineering either the 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol 4-phosphate (MEP) pathway or mevalonate (MVA) pathway in microorganisms. To further improve lycopene production, it is critical to utilize metabolic enzymes with high specific activities. Two enzymes, 1-deoxy-d-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase (Dxs) and farnesyl diphosphate synthase (IspA), are required in lycopene production using MEP pathway. Here, we evaluated the activities of Dxs and IspA of Vibrio sp. dhg, a newly isolated and fast-growing microorganism. -

Vitamins a and E and Carotenoids

Fat-Soluble Vitamins & Micronutrients: Vitamins A and E and Carotenoids Vitamins A (retinol) and E (tocopherol) and the carotenoids are fat-soluble micronutrients that are found in many foods, including some vegetables, fruits, meats, and animal products. Fish-liver oils, liver, egg yolks, butter, and cream are known for their higher content of vitamin A. Nuts and seeds are particularly rich sources of vitamin E (Thomas 2006). At least 700 carotenoids—fat-soluble red and yellow pigments—are found in nature (Britton 2004). Americans consume 40–50 of these carotenoids, primarily in fruits and vegetables (Khachik 1992), and smaller amounts in poultry products, including egg yolks, and in seafoods (Boylston 2007). Six major carotenoids are found in human serum: alpha-carotene, beta-carotene, beta-cryptoxanthin, lutein, trans-lycopene, and zeaxanthin. Major carotene sources are orange-colored fruits and vegetables such as carrots, pumpkins, and mangos. Lutein and zeaxanthin are also found in dark green leafy vegetables, where any orange coloring is overshadowed by chlorophyll. Trans-Lycopene is obtained primarily from tomato and tomato products. For information on the carotenoid content of U.S. foods, see the 1998 carotenoid database created by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Nutrition Coordinating Center at the University of Minnesota (http://www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/foodcomp/Data/car98/car98.html). Vitamin A, found in foods that come from animal sources, is called preformed vitamin A. Some carotenoids found in colorful fruits and vegetables are called provitamin A; they are metabolized in the body to vitamin A. Among the carotenoids, beta-carotene, a retinol dimer, has the most significant provitamin A activity. -

Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine Page 0

77:222 Spring 2005 Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine Page 0 This student paper was written as an assignment in the graduate course Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine (77:222, Spring 2005) offered by the Free Radical and Radiation Biology Program B-180 Med Labs The University of Iowa Iowa City, IA 52242-1181 Spring 2005 Term Instructors: GARRY R. BUETTNER, Ph.D. LARRY W. OBERLEY, Ph.D. with guest lectures from: Drs. Freya Q . Schafer, Douglas R. Spitz, and Frederick E. Domann The Fine Print: Because this is a paper written by a beginning student as an assignment, there are no guarantees that everything is absolutely correct and accurate. In view of the possibility of human error or changes in our knowledge due to continued research, neither the author nor The University of Iowa nor any other party who has been involved in the preparation or publication of this work warrants that the information contained herein is in every respect accurate or complete, and they are not responsible for any errors or omissions or for the results obtained from the use of such information. Readers are encouraged to confirm the information contained herein with other sources. All material contained in this paper is copyright of the author, or the owner of the source that the material was taken from. This work is not intended as a threat to the ownership of said copyrights. S. Jetawattana Lycopene, a powerful antioxidant 1 Lycopene, a powerful antioxidant by Suwimol Jetawattana Department of Radiation Oncology Free Radical and Radiation Biology The University -

Β-Carotene Content of Some Commonly Consumed Vegetables

ition & F tr oo u d N f S o c Pritwani and Mathur, J Nutr Food Sci 2017, 7:5 l i e a n n r c DOI: 10.4172/2155-9600.1000625 e u s o J Journal of Nutrition & Food Sciences ISSN: 2155-9600 Research Article Open Access β-carotene Content of Some Commonly Consumed Vegetables and Fruits Available in Delhi, India Richa Pritwani* and Pulkit Mathur Department of Food and Nutrition, Lady Irwin College, University of Delhi, New Delhi, 110001, India Abstract Most of the vitamin A in the diet comes from plant food sources in developing countries. This study was designed with an objective of determining β-carotene content of a total of 26 types of green leafy vegetables, tubers, other vegetables and fruits obtained from four wholesale markets in Delhi, India using HPLC. There was a wide variation in β-carotene content of green leafy vegetables, with means ranging from 2199 µg/100 g in Basella rubra to 7753 µg/100 g in Amaranthus gangeticus. A large variation was observed in β-carotene content of fruits and the mango varieties tested, ranging from undetectable levels in strawberry and 808.60 µg/100 g in totapuri mango up to 11789 µg/100 g in alphonso mango. Approximately 65 g and 100 g of a green leafy vegetable would meet daily requirement of a preschooler and older child/adult respectively. Mango has considerable amount of β-carotene, and consuming a medium-sized bowl by preschool children would meet 99% of Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDA). The information generated is useful in identifying types of fruits and vegetables with higher concentration of the provitamin A in low income economies where fruits and vegetables are expensive. -

Lycopene and Beta-Carotene Induce Cell-Cycle Arrest and Apoptosis in Human Breast Cancer Cell Lines

ANTICANCER RESEARCH 34: 1377-1386 (2014) Lycopene and Beta-carotene Induce Cell-Cycle Arrest and Apoptosis in Human Breast Cancer Cell Lines NATHALIE FONSECA GLORIA1, NATHALIA SOARES2, CAMILA BRAND2, FELIPE LEITE OLIVEIRA2, RADOVAN BOROJEVIC3 and ANDERSON JUNGER TEODORO1 1Laboratory of Nutritional Biochemistry, Program of Food and Nutrition, UNIRIO, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; 2Laboratory of Cell Proliferation and Differentiation, Institute of Biomedical Sciences, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; 3Excellion Biomedical Services, Petrópolis, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Abstract. Lycopene and beta-carotene are carotenoids Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed type of widely distributed in fruits and vegetables, with potential cancer globally (1), and is a complex disease caused by anticancer activity. Epidemiological trials rarely provide progressive genetic mutations, associated with other factors. evidence for the mechanisms of action of these compounds, The increased incidence of breast cancer follows the and their biological effects at different times of treatment are behavioral changes of urbanization, such as a sedentary still unclear. The aim of the present study was to determine lifestyle, excess of processed food in the diet, overweight the effect of carotenoids on the cell cycle and cell viability and obesity (2, 3). in human breast cancer cell lines. Human breast cell lines Diets enriched in fruits and vegetables are associated with were treated with carotenoids (0.5-10 μM) for 48 and 96 h. reduced rates of cancer and coronary heart disease. Bioactive Cell viability was monitored using the MTT method (3-[4,5- compounds present in the diet have been reported as dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5- diphenyltetrazolium bromide; substances responsible for these effects. -

Conversion of Dietary Carotenoids and Vitamin a Into Bioactive Retinoids

24 CONVERSION OF DIETARY CAROTENOIDS AND VITAMIN A INTO BIOACTIVE RETINOIDS Conversion of Dietary Carotenoids and Vitamin A into Bioactive Retinoids: Exploring trails blazed by Jim Olson James Allen Olson Memorial Lecture Earl H Harrison fects millions of children and women in the developing world. Ohio State University, Columbus, USA The widespread morbidity and mortality associated with the deficiency reflects the fact that the active forms of vitamin A (retinoids) are critical signaling molecules necessary in higher vertebrates for embryonic development, the regulation of gene transcription, visual transduction, immune function, and the control of metabolic processes. In spite of their importance in vertebrate development and physiology, the capability for the biosynthesis of molecules with retinoid activities is restricted to plants and microorganisms. Thus, animals, including humans, must obtain the essential vitamin A from the diet. Vitamin A ac- tivity in the diet comes from two sources: preformed vitamin A as retinyl esters in foods of animal origin, and provitamin A ca- rotenoids, such as β-carotene, α-carotene, and β-cryptoxanthin, found in plant-derived foods. Indeed, in areas of the world with vitamin A deficiency, the major source of vitamin A is dietary carotenoids. While the chemical and nutritional relationships of provita- min A carotenoids and vitamin A were appreciated by the 1930s it was in the last half of the 20th century that great advances in our understanding of metabolism, function, and public health significance of carotenoids and vitamin A led us to our current state of knowledge in these fields. While these advances were James Allen Olson the results of the efforts of many basic scientists, clinicians, and public health experts, James Allen Olson stands out as one of the giants in the fields of vitamin A and carotenoids. -

Beta-Carotene: How Safe and Effective?

BETA-CAROTENE: HOW SAFE AND EFFECTIVE? Beta-carotene, a plant compound that can be converted by the body into vitamin A, has interested nutrition researchers over the last several years. It, along with vitamin C and vitamin E, are believed to be strong antioxidants and thereby protect people against certain cancers, including lung cancer, coronary heart disease, certain eye disorders and other chronic ailments. The beta-carotene findings were quickly noted by vitamin manufacturers, health food store proprietors, and alternative medicine practitioners and they seized upon the opportunity to promote antioxidant vitamins including beta-carotene. On the basis of these and other studies, some of the leading nutritionists in the country have also suggested that taking beta-carotene supplements might be a good thing. To test it, some major research trials were started using approved scientific procedures. Two of these studies have not been reported and the news is not good. One, known as the Physician's Health study of 22,071 male physicians, used high beta-carotene supplements of 50 milligrams every other day. After 12 years there was no evidence that the supplement had provided any benefit and some people developed yellow skin and minor gastrointestinal symptoms. In the CARET study, both vitamin A and beta-carotene were given daily for an average of four years to 18,314 current or former smokers or to those who had been asbestos workers. The trial was cut short because preliminary evaluation showed that the subjects given high levels of beta carotene and vitamin A had more lung cancer and more deaths, from lung cancer and from cardiovascular disease than those without any treatment. -

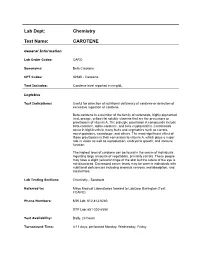

Lab Dept: Chemistry Test Name: CAROTENE

Lab Dept: Chemistry Test Name: CAROTENE General Information Lab Order Codes: CARO Synonyms: Beta Carotene CPT Codes: 82380 - Carotene Test Includes: Carotene level reported in mcg/dL. Logistics Test Indications: Useful for detection of nutritional deficiency of carotene or detection of excessive ingestion of carotene. Beta-carotene is a member of the family of cartenoids, highly pigmented (red, orange, yellow) fat soluble vitamins that are the precursors or provitamins of vitamin A. The principle provitamin A compounds include beta-carotene, alpha-carotene, and beta-cryptoxanthin. Carotenoids occur in high levels in many fruits and vegetables such as carrots, sweet potatoes, cantaloupe, and others. The most significant effect of these provitamins is their conversion to vitamin A, which plays a major role in vision as well as reproduction, embryonic growth, and immune function. The highest level of carotene can be found in the serum of individuals ingesting large amounts of vegetables, primarily carrots. These people may have a slight yellowish tinge of the skin but the sclera of the eye is not discolored. Decreased serum levels may be seen in individuals with nutritional deficiencies including anorexia nervosa, malabsorption, and steatorrhea. Lab Testing Sections: Chemistry - Sendouts Referred to: Mayo Medical Laboratories forward to LabCorp Burlington (Test: FCARO) Phone Numbers: MIN Lab: 612-813-6280 STP Lab: 651-220-6550 Test Availability: Daily, 24 hours Turnaround Time: 4-11 days, performed Monday, Wednesday, Friday Special Instructions: See Patient Preparation Specimen Specimen Type: Blood Container: SST (Gold, marble or red) tube Draw Volume: 3 mL (Minimum: 1.5 mL) blood Processed Volume: 1 mL (Minimum: 0.5 mL) serum Collection: Routine venipuncture Special Processing: Lab Staff: Centrifuge specimen, remove serum aliquot into an amber MML tube (Supply T192) to protect from light.