Active Labour Market Policies and Labour Market Transitions in Denmark: an Analysis of Event History Data

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Referral of Paediatric Patients Follows Geographic Borders of Administrative Units

Dan Med Bul ϧϪ/Ϩ June ϤϢϣϣ DANISH MEDICAL BULLETIN ϣ Referral of paediatric patients follows geographic borders of administrative units Poul-Erik Kofoed1, Erik Riiskjær2 & Jette Ammentorp3 ABSTRACT e ffect of economic incentives rooted in local govern- ORIGINAL ARTICLE INTRODUCTION: This observational study examines changes ment’s interest in maximizing the number of patients 1) Department in paediatric hospital-seeking behaviour at Kolding Hospital from their own county/region who are treated at the of Paediatrics, in The Region of Southern Denmark (RSD) following a major county/region’s hospitals in order not to have to pay the Kolding Hospital, change in administrative units in Denmark on 1 January higher price at hospitals in other regions or in the pri- 2) School of 2007. vate sector. Treatment at another administrative unit is Economics and MATERIAL AND METHODS: Data on the paediatric admis- Management, usually settled with 100% of the diagnosis-related group University of sions from 2004 to 2009 reported by department of paedi- (DRG) value, which is not the case for treatment per - Aarhus, and atrics and municipalities were drawn from the Danish formed at hospitals within the same administrative unit. 3) Health Services National Hospital Registration. Patient hospital-seeking On 1 January 2007, the 13 Danish counties were Research Unit, behaviour was related to changes in the political/admini s- merged into five regions. The public hospitals hereby Kolding Hospital/ trative units. Changes in number of admissions were com- Institute of Regional became organized in bigger administrative units, each pared with distances to the corresponding departments. Health Services with more hospitals than in the previous counties [7]. -

NOSOCOMIAL OUTBREAK of SCABIES in VIBORG COUNTY No

EPI-NEWS NATIONAL SURVEILLANCE OF COMMUNICABLE DISEASES Editor: Tove Rønne Statens Serum Institut - 5 Artillerivej - 2300 Copenhagen S - Denmark Tel.: +45 3268 3268 - Fax: +45 3268 3868 www.ssi.dk - [email protected] - ISSN: 1396-4798 NOSOCOMIAL OUTBREAK OF SCABIES IN VIBORG COUNTY No. 7, 2001 Fig. 1. Nosocomial outbreak of scabies in Viborg County, June 2000-January 2001 Index case Fellow patients Relatives / other Hospital / nursing home staff Home care staff Hospital, Mors Nursing home Nursing Hospital, Kjellerup Hospital, Home care, Mors Home Mors care, Hospital, Viborg Index case In the second week of October 2000 index case, who never left his single having scabies as part of an unbro- a sizeable nosocomial outbreak of room. Several of these patients ken chain of infection: the index scabies was noted at Nykøbing Mors passed the infestation on, Fig. 1. case, 24 fellow patients, 19 relatives, Hospital. The spread was presuma- Seven employees were infected. 13 hospital employees, eight nur- bly from a patient (the index case) Nearly all the patients who were in- sing-home employees, 11 home care admitted to a medical ward in mid- fected at the hospital during July- assistants and one other. The index July. This patient died 10 days later August were getting home nursing case and two fellow patients had sca- from a malignancy, and scabies was or lived in a nursing home. A total of bies norvegica, in which the number not suspected during the admission. 11 employees in six home-care dis- of scabies mites in the skin is many In mid-June the patient had spent tricts were infected. -

A Meta Analysis of County, Gender, and Year Specific Effects of Active Labour Market Programmes

A Meta Analysis of County, Gender, and Year Speci…c E¤ects of Active Labour Market Programmes Agne Lauzadyte Department of Economics, University of Aarhus E-Mail: [email protected] and Michael Rosholm Department of Economics, Aarhus School of Business E-Mail: [email protected] 1 1. Introduction Unemployment was high in Denmark during the 1980s and 90s, reaching a record level of 12.3% in 1994. Consequently, there was a perceived need for new actions and policies in the combat of unemployment, and a law Active Labour Market Policies (ALMPs) was enacted in 1994. The instated policy marked a dramatic regime change in the intensity of active labour market policies. After the reform, unemployment has decreased signi…cantly –in 1998 the unemploy- ment rate was 6.6% and in 2002 it was 5.2%. TABLE 1. UNEMPLOYMENT IN DANISH COUNTIES (EXCL. BORNHOLM) IN 1990 - 2004, % 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 Country 9,7 11,3 12,3 8,9 6,6 5,4 5,2 6,4 Copenhagen and Frederiksberg 12,3 14,9 16 12,8 8,8 5,7 5,8 6,9 Copenhagen county 6,9 9,2 10,6 7,9 5,6 4,2 4,1 5,3 Frederiksborg county 6,6 8,4 9,7 6,9 4,8 3,7 3,7 4,5 Roskilde county 7 8,8 9,7 7,2 4,9 3,8 3,8 4,6 Western Zelland county 10,9 12 13 9,3 6,8 5,6 5,2 6,7 Storstrøms county 11,5 12,8 14,3 10,6 8,3 6,6 6,2 6,6 Funen county 11,1 12,7 14,1 8,9 6,7 6,5 6 7,3 Southern Jutland county 9,6 10,6 10,8 7,2 5,4 5,2 5,3 6,4 Ribe county 9 9,9 9,9 7 5,2 4,6 4,5 5,2 Vejle county 9,2 10,7 11,3 7,6 6 4,8 4,9 6,1 Ringkøbing county 7,7 8,4 8,8 6,4 4,8 4,1 4,1 5,3 Århus county 10,5 12 12,8 9,3 7,2 6,2 6 7,1 Viborg county 8,6 9,5 9,6 7,2 5,1 4,6 4,3 4,9 Northern Jutland county 12,9 14,5 15,1 10,7 8,1 7,2 6,8 8,7 Source: www.statistikbanken.dk However, the unemployment rates and their evolution over time di¤er be- tween Danish counties, see Table 1. -

The Danish Design Industry Annual Mapping 2005

The Danish Design Industry Annual Mapping 2005 Copenhagen Business School May 2005 Please refer to this report as: ʺA Mapping of the Danish Design Industryʺ published by IMAGINE.. Creative Industries Research at Copenhagen Business School. CBS, May 2005 A Mapping of the Danish Design Industry Copenhagen Business School · May 2005 Preface The present report is part of a series of mappings of Danish creative industries. It has been conducted by staff of the international research network, the Danish Research Unit for Industrial Dynamics, (www.druid.dk), as part of the activities of IMAGINE.. Creative Industries Research at the Copenhagen Business School (www.cbs.dk/imagine). In order to assess the future potential as well as problems of the industries, a series of workshops was held in November 2004 with key representatives from the creative industries covered. We wish to thank all those who gave generously of their time when preparing this report. Special thanks go to Nicolai Sebastian Richter‐Friis, Architect, Lundgaard & Tranberg; Lise Vejse Klint, Chairman of the Board, Danish Designers; Steinar Amland, Director, Danish Designers; Jan Chul Hansen, Designer, Samsøe & Samsøe; and Tom Rossau, Director and Designer, Ichinen. Numerous issues were discussed including, among others, market opportunities, new technologies, and significant current barriers to growth. Special emphasis was placed on identifying bottlenecks related to finance and capital markets, education and skill endowments, labour market dynamics, organizational arrangements and inter‐firm interactions. The first version of the report was drafted by Tina Brandt Husman and Mark Lorenzen, the Danish Research Unit for Industrial Dynamics (DRUID) and Department of Industrial Economics and Strategy, Copenhagen Business School, during the autumn of 2004 and finalized for publication by Julie Vig Albertsen, who has done sterling work as project leader for the entire mapping project. -

Member Directory

Member Directory The Delegation of Denmark to the OSCE PA Mr. Peter Juel Jensen Head of Delegation Folketinget Christiansborg 1240 Copenhagen K DENMARK Telephone: +45 61624628 Fax: Political Party Affiliation: The Liberal Party Home District Bornholm Constituency Member of Parliament since 2007 Positions held in Parliament: Vice-chairman of the Environment and Regional Planning Committee from 2007. Member of the Labour Market Committee and the Naturalisation Committee from 2007. Current positions in Parliament: Spokesman for Defense Educational background: Basic vocational education (EFG) and Higher Commercial Examination (HH), Bornholm Vocational School, Rønne 1984- 1987. Other information: Peter Juel Jensen, born May 18th 1966 in Rønne, son of former business manager Jens Juel Jensen and former mayoress Birthe Juel Jensen. Married to Lena Buus Larsen. They have four children Jeppe, born in 2002, Rasmus, born in 2004, Asta-Maria, born in 2006 and Kasper, born in 1991. Profession Teacher, Hjørring College of Education 1996-2000. Officer of the line, Frederiksberg Castle 1991-1993. Chairman for OSCE PA and NATO PA Delegations, Chairman of Countryside Committee Affiliations Chairman of HOC, Principal Organisation of Officers at Frederiksberg Castle, 1992 - 1993. Chairman of the Student Council at Hjørring College of Education, 1996 - 2000. Member of Bornholm County Council, 2001, member of the cultural affairs and social services committee. Member of Aakirkeby Municipal Council, 2001 - 2006, technology and environment committee and the finance committee. Chairman of Bornholm Academy, 2001 - 2007. Chairman of the education council at Åvang School in Rønne, 2002 - 2004. Member of Bornholm Region Council, 2002 - 2007, technology and environment committee, and trade and industry and labour market committee and member of the employment committee, 2005 - 2007, resigned in connection with the 2007 general election. -

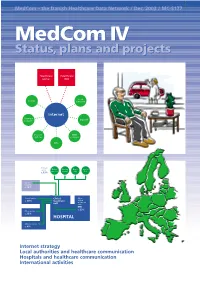

Medcom IV Status, Plans and Projects

MedCom – the Danish Healthcare Data Network / Dec. 2003 / MC-S177 MedComMedCom IV IV Status,Status, plans plans andand projectsprojects Healthcare Healthcare portal DIX Local County authority Internet Pharmacy Dan Net network Doctors’ KMD systems network KPLL Primary sector Medical Nursing Home Specia- practice homes care lists c. 13% Other hospitals c. 10% Clinical service Clinical Other c. 40% treatment clinical treatment unit units EPR c. 23% Other service c. 13% HOSPITAL Administration c. 4% ● Internet strategy ● Local authorities and healthcare communication ● Hospitals and healthcare communication ● International activities 2 MedCom IV – status, plans and projects Contents Aims of MedCom 2 The local authorities and healthcare communication 20 Introduction 3 The Hospital-Local Authority XML project 20 Healthcare on the move 3 The Hospital-Local Authority project and Common Language 22 History 4 Commentary: The Minister of Social Affairs, Henriette Kjær 22 The MedCom steering group 6 The LÆ form project 23 Commentary: The Minister of the Interior and Commentary: The Chairman of the National Health, Lars Løkke Rasmussen 7 Association of Local Authorities, Perspective: MedCom certifies communication 8 Ejgil W. Rasmussen 24 Perspective: The IT Lighthouse’s local authority- The Internet strategy 9 medical practice communication 24 The infrastructure project 9 The hospitals and Commentary: The Chairman of the Association of healthcare communication 25 County Councils, Kristian Ebbensgaard 12 Perspective: The Internet strategy and the From -

The Cimbri of Denmark, the Norse and Danish Vikings, and Y-DNA Haplogroup R-S28/U152 - (Hypothesis A)

The Cimbri of Denmark, the Norse and Danish Vikings, and Y-DNA Haplogroup R-S28/U152 - (Hypothesis A) David K. Faux The goal of the present work is to assemble widely scattered facts to accurately record the story of one of Europe’s most enigmatic people of the early historic era – the Cimbri. To meet this goal, the present study will trace the antecedents and descendants of the Cimbri, who reside or resided in the northern part of the Jutland Peninsula, in what is today known as the County of Himmerland, Denmark. It is likely that the name Cimbri came to represent the peoples of the Cimbric Peninsula and nearby islands, now called Jutland, Fyn and so on. Very early (3rd Century BC) Greek sources also make note of the Teutones, a tribe closely associated with the Cimbri, however their specific place of residence is not precisely located. It is not until the 1st Century AD that Roman commentators describe other tribes residing within this geographical area. At some point before 500 AD, there is no further mention of the Cimbri or Teutones in any source, and the Cimbric Cheronese (Peninsula) is then called Jutland. As we shall see, problems in accomplishing this task are somewhat daunting. For example, there are inconsistencies in datasources, and highly conflicting viewpoints expressed by those interpreting the data. These difficulties can be addressed by a careful sifting of diverse material that has come to light largely due to the storehouse of primary source information accessed by the power of the Internet. Historical, archaeological and genetic data will be integrated to lift the veil that has to date obscured the story of the Cimbri, or Cimbrian, peoples. -

Medcom 2 in Print (Pdf)

MedCom MC-S117 / December 1999 -the Danish Health Care Data Network MedCom2MedCom2 inin print print Ministry of Health Ministry of Social Affairs The National Board of Health Association of County Councils in Denmark The National Association of Local Authorities in Denmark Copenhagen Hospital Corporation Copenhagen and Frederiksberg Local Authorities Danish Pharmaceutical Association Danish Dental Association Association of Danish Doctors Kommunedata Tele Danmark Dan Net The MedCom project A nation-wide network and EPR implementation, which takes place in the hospitals. MedCom is a project involving co- operation between authorities, The parties behind the permanent healthcare organisations and priv- MedCom are the Ministry of ate companies linked to the health- Health, the Association of County care sector. The purpose behind Councils in Denmark, the National this co-operation is to establish and Board of Health, Copenhagen MedCom 1 (1994 - 96) continue the development of a Hospital Corporation, Copenhagen had the purpose of coherent Danish healthcare data and Frederiksberg Local Authori- G developing communication stan- network. ties, the Danish Pharmaceutical dards for the most common com- Association, the Association of munication flows between medical MedCom is to contribute towards Danish Doctors and Dan Net. practices, hospitals and pharmacies. implementing the Danish Govern- ment’s IT policy action plan for the MedCom 1, 2 and 3 MedCom 2 (1997 - 99) healthcare sector, including conti- MedCom activities are carried out had the purpose of nuing the dissemination and quali- as projects for defined periods of G developing communication stan- ty assurance of electronic commu- time, and each project period con- dards for the most common com- nication. -

The Significance of the Shoulder Season of Hotel Nights - Evidence from Denmark in a Nordic Perspective

50 th Congress of the European Regional Science Association The Significance of the Shoulder Season of Hotel Nights - Evidence from Denmark in a Nordic Perspective Nils Karl Sørensen 1, University of Southern Denmark e-mail: [email protected] Abstract During the past decades, the role of the shoulder season has gained increasing attention. It is obvious that an expansion of the length of the high season with the shoulder season will have a positive effect on labor demand and income in a given region. The purpose of this paper is to address the issue of the shoulder season in a time series framework. Departing from a discussion of the nature of types of seasonal variation, a test is set up in order to examine the impact of the shoulder season. The test examines the impact on the mean share of hotel nights in the shoulder season months in two different periods. The method is applied on a monthly data set on hotel nights ranging for 37 years by regions of Denmark. A much-diversified picture is revealed. In general, the shoulder season of October has increased significance. For rural counties such as Storstroem, Ribe and North Jutland positive effects are observed for other months as well. However, we find for many other rural areas no significant effect. In order to examine the validity of this approach, a discussion is provided with evidence for Norway and Finland. Here different pictures are revealed highlighting the significance of winter tourism relative to Denmark. The different implications on the economy are discussed, and issues are given on development. -

National Forest Stewardship Standard of Denmark

The FSC National Forest Steward- ship Standard of Denmark FSC International Center GmbH · ic.fsc.org · FSC® F000100 Adenauerallee 134 · 53113 Bonn · Germany T +49 (0) 228 367 66 0 · F +49 (0) 228 367 66 30 Geschäftsführer | Director: Dr. Hans-Joachim Droste Handelsregister | Commercial Register: Bonn HRB12589 Forest Stewardship Council® Title The FSC National Forest Stewardship Standard of Denmark Document reference code: FSC-STD-DNK-02-2018 All forest types and sizes Status: Approved Geographical Scope: National Forest Scope All forest types and sizes Approval body Policy and Standards Committee Submission date 27. November 2017 Approval date: 9. February 2018 Effective date: 24. September 2018 Validity Period: Five (5) years starting from the effective date. FSC Denmark Website: www.fsc.dk Country Contact: Sofie Tind Nielsen, Standard facilitator and technical advisor Ferdinand Sallings Stræde 13, 3. Sal, 8000 Aarhus C Ph.: +45 8870 9518, mail: [email protected] / [email protected] FSC International Center - Performance and Standards Unit - FSC Performance and Standards Adenauerallee 134, 53113 Bonn, Germany Unit Contact +49-(0)228-36766-0 +49-(0)228-36766-30 [email protected] A.C. All rights reserved. No part of this work covered by the publisher’s copyright may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means (graphic, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, recording taping, or information retrieval systems) without the written permission of the publisher. The Forest Stewardship Council® (FSC) is an independent, not for profit, non-government organization es- tablished to support environmentally appropriate, socially beneficial, and economically viable management of the world's forests. -

Irritable Bowel Symptoms and the Development of Common Mental

Irritable bowel symptoms and the development of common mental disorders and functional somatic syndromes identified in secondary care a long-term, population-based study Poulsen, Chalotte Heinsvig; Eplov, Lene Falgaard; Hjorthøj, Carsten; Eliasen, Marie; Skovbjerg, Sine; Dantoft, Thomas Meinertz; Schröder, Andreas; Jørgensen, Torben Published in: Clinical Epidemiology DOI: 10.2147/CLEP.S141344 Publication date: 2017 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Document license: CC BY-NC Citation for published version (APA): Poulsen, C. H., Eplov, L. F., Hjorthøj, C., Eliasen, M., Skovbjerg, S., Dantoft, T. M., Schröder, A., & Jørgensen, T. (2017). Irritable bowel symptoms and the development of common mental disorders and functional somatic syndromes identified in secondary care: a long-term, population-based study. Clinical Epidemiology, 9, 393-402. https://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S141344 Download date: 23. Sep. 2021 Journal name: Clinical Epidemiology Article Designation: ORIGINAL RESEARCH Year: 2017 Volume: 9 Clinical Epidemiology Dovepress Running head verso: Poulsen et al Running head recto: Prognosis of the irritable bowel syndrome open access to scientific and medical research DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S141344 Open Access Full Text Article ORIGINAL RESEARCH Irritable bowel symptoms and the development of common mental disorders and functional somatic syndromes identified in secondary care – a long-term, population-based study Chalotte Heinsvig Objective: Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is associated with mental vulnerability, and half of Poulsen1,2 patients report comorbid somatic and mental symptoms. We aimed to investigate the relation- Lene Falgaard Eplov2 ship between an IBS symptom continuum and the subsequent development of common mental Carsten Hjorthøj2 disorders (CMDs) and functional somatic syndromes (FSSs). -

Regional Trends in Breast Cancer Incidence and Mortality in Denmark Prior to Mammographic Screening

Br. J. Cancer (1994), 76, 133-137 C) Macmi-Ban Press Ltd., 1994 Br. J. Cancer (1994), 76, 133-137 C Mwnlllan Press Ltd., 1994~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Regional trends in breast cancer incidence and mortality in Denmark prior to mammographic screening A.H. Andreasen', K.W. Andersen2, M. Madsen3, H. Mouridsen2, K.P. Olesen4 & E. Lyngel 'Danish Cancer Society, Strandbouevarden 49, DK-2100N Copehagen 0; 2Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group, Rigshospitalet, Tagensvej 20, DK-2200 Copnhgen N; 3Danish Institutefor Clinical Epidemiology, Swanmllewej 25, DK-2100 Copenhagen 0; 'The Mammograpi Clinic, Birpebjerg Hospital, Bispebjerg Bakke 23, DK-24(X Copenhagen NV, Denmark. Sm_y To provide a basis for the evaluation of screning programmes in Dnmark, a study was undertaken of the regioal dierces i breast car i e and mortality. AJI 16 regions wer followed for the 20 year period, 1970-89, before the start of the first population-based p b e programme m the Copenhagen ty in 1991. Multiplicative Poisson models wer used for the analysis. In general, the icideK icrsed during this period from 55 to 70 [pr 100,000 standardised world andard pulation (WSP)l and the analysis shows this to be most pronounced among won below age 60. The mortaity was more stabl, changing only from 24 to 28 (per 100,000 standardised WSP), but a signifiant icse ed in the late 198(6k lhe study showd regional diffes in both i and mortality of brast cancer in Dnmark Both the inidence and the mortaity aried between the regions, with maximum differe:ees of 22%. The analyss showed no variaton m the tim trends in the different regios, and thus te that the use of a regional comprison group would be a valid basas for evaluation of the protgamm.