Ritual As the Way to Speak in Dancing at Lughnasa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read Aeschylus The Persians (472 BC) McCullers A Member of the Wedding The Orestia (458 BC) (1946) Prometheus Bound (456 BC) Miller Death of a Salesman (1949) Sophocles Antigone (442 BC) The Crucible (1953) Oedipus Rex (426 BC) A View From the Bridge (1955) Oedipus at Colonus (406 BC) The Price (1968) Euripdes Medea (431 BC) Ionesco The Bald Soprano (1950) Electra (417 BC) Rhinoceros (1960) The Trojan Women (415 BC) Inge Picnic (1953) The Bacchae (408 BC) Bus Stop (1955) Aristophanes The Birds (414 BC) Beckett Waiting for Godot (1953) Lysistrata (412 BC) Endgame (1957) The Frogs (405 BC) Osborne Look Back in Anger (1956) Plautus The Twin Menaechmi (195 BC) Frings Look Homeward Angel (1957) Terence The Brothers (160 BC) Pinter The Birthday Party (1958) Anonymous The Wakefield Creation The Homecoming (1965) (1350-1450) Hansberry A Raisin in the Sun (1959) Anonymous The Second Shepherd’s Play Weiss Marat/Sade (1959) (1350- 1450) Albee Zoo Story (1960 ) Anonymous Everyman (1500) Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf Machiavelli The Mandrake (1520) (1962) Udall Ralph Roister Doister Three Tall Women (1994) (1550-1553) Bolt A Man for All Seasons (1960) Stevenson Gammer Gurton’s Needle Orton What the Butler Saw (1969) (1552-1563) Marcus The Killing of Sister George Kyd The Spanish Tragedy (1586) (1965) Shakespeare Entire Collection of Plays Simon The Odd Couple (1965) Marlowe Dr. Faustus (1588) Brighton Beach Memoirs (1984 Jonson Volpone (1606) Biloxi Blues (1985) The Alchemist (1610) Broadway Bound (1986) -

Undergraduate Play Reading List

UND E R G R A DU A T E PL A Y R E A DIN G L ISTS ± MSU D EPT. O F T H E A T R E (Approved 2/2010) List I ± plays with which theatre major M E DI E V A L students should be familiar when they Everyman enter MSU Second 6KHSKHUGV¶ Play Hansberry, Lorraine A Raisin in the Sun R E N A ISSA N C E Ibsen, Henrik Calderón, Pedro $'ROO¶V+RXVH Life is a Dream Miller, Arthur de Vega, Lope Death of a Salesman Fuenteovejuna Shakespeare Goldoni, Carlo Macbeth The Servant of Two Masters Romeo & Juliet Marlowe, Christopher A Midsummer Night's Dream Dr. Faustus (1604) Hamlet Shakespeare Sophocles Julius Caesar Oedipus Rex The Merchant of Venice Wilder, Thorton Othello Our Town Williams, Tennessee R EST O R A T I O N & N E O-C L ASSI C A L The Glass Menagerie T H E A T R E Behn, Aphra The Rover List II ± Plays with which Theatre Major Congreve, Richard Students should be Familiar by The Way of the World G raduation Goldsmith, Oliver She Stoops to Conquer Moliere C L ASSI C A L T H E A T R E Tartuffe Aeschylus The Misanthrope Agamemnon Sheridan, Richard Aristophanes The Rivals Lysistrata Euripides NIN E T E E N T H C E N T UR Y Medea Ibsen, Henrik Seneca Hedda Gabler Thyestes Jarry, Alfred Sophocles Ubu Roi Antigone Strindberg, August Miss Julie NIN E T E E N T H C E N T UR Y (C O N T.) Sartre, Jean Shaw, George Bernard No Exit Pygmalion Major Barbara 20T H C E N T UR Y ± M ID C E N T UR Y 0UV:DUUHQ¶V3rofession Albee, Edward Stone, John Augustus The Zoo Story Metamora :KR¶V$IUDLGRI9LUJLQLD:RROI" Beckett, Samuel E A R L Y 20T H C E N T UR Y Waiting for Godot Glaspell, Susan Endgame The Verge Genet Jean The Verge Treadwell, Sophie The Maids Machinal Ionesco, Eugene Chekhov, Anton The Bald Soprano The Cherry Orchard Miller, Arthur Coward, Noel The Crucible Blithe Spirit All My Sons Feydeau, Georges Williams, Tennessee A Flea in her Ear A Streetcar Named Desire Synge, J.M. -

Dancing at Lughnasa

1 Dancing at Lughnasa ACT ONE When the play opens MICHAEL is standing downstage left in a pool of light. The rest of the stage is in darkness. Immediately MICHAEL begins speaking slowly bring up the lights on the rest of the stage. Around the stage and at a distance from MICHAEL the other characters stand motionless in formal tableau. MAGGIE is at the kitchen window (right). CHRIS is at the front door. KATE at extreme stage right. ROSE and GERRY sit on the garden seat. JACK stands beside ROSE. AGNES is upstage left. They hold these positions while MICHAEL talks to the audience. MICHAEL. When I cast my mind back to that summer of 1936 different kinds of memories offer themselves to me. We got our first wireless set that summer – well, a sort of set; and it obsessed us. And because it arrived as August was about too begin, my Aunt Maggie – She was the joker of the family – she suggested we give it a name. She wanted to call it Lugh* after the old Celtic God of the Harvest. Because in the old days August the First was La Lughnasa, the feast day of the pagan god, Lugh; and the days and weeks of harvesting that followed were called the Festival of Lughnasa. But Aunt Kate – she was a national schoolteacher and a very proper woman --she said it would be sinful to christen an inanimate object with any kind of name, not to talk of a pagan god. So we just called it Marconi because that was the name emblazoned on the set. -

Pathlight Magazine and Comma Press

PATHLIGHT SPRING / 2015 Spring 2015 ISBN 978-7-119-09418-2 © Foreign Languages Press Co. Ltd, Beijing, China, 2015 Published by Foreign Languages Press Co. Ltd. 24 Baiwanzhuang Road, Beijing 100037, China http://www.flp.com.cn E-mail: [email protected] Distributed by China International Book Trading Corporation 35 Chegongzhuang Xilu, Beijing 100044, China P.O. Box 399, Beijing, China Printed in the People’s Republic of China CONTENTS Hai Zi Autumn 4 On the Great Plain a Great Snow Seals off the Mountains Swan Words West of the Vineyard Wu Ming-yi Death is a Tiger Butterfly 8 Deng Yiguang Wolves Walk Atwain 18 Gerelchimig Blackcrane The Nightjar at Dusk 28 Sun Yisheng Apery 38 Cai Shiping Wasted Towns and Broken Rooms 48 Thicketing of Shadows Toothache Red The Mountain Spirit A Bird Sings on a Flowered Branch Liu Liangcheng A Village of One 56 Shu Jinyu Liu Liangcheng: Literature Only Begins Where the Story Ends 66 Luo Yihe snowing and snowing 74 the moon white tiger the great river Rong Guangqi After the Rain 80 Full Moon Metal Squirrel Wei An Going into the White Birch Forest 84 Thoreau and I 86 Xia Jia Heat Island 92 Ye Zhou Nature’s Perfume 104 Nine Horse Prairie Qinghai Skies Zhou Xiaofeng The Great Whale Sings 110 Qiu Lei Illusory Constructions 122 Shao Bing Clear Water Castle 132 Wang Zu Snowfall 136 Shu Jinyu Ouyang Jianghe: Resistance and the Long Poem 144 Li Shaojun The Legend of the Sea 150 Mount Jingting Idle Musings in Spring Liu Qingbang Pigeon 154 Zhang Wei Rain and Snow 164 Ye Mi The Hot Springs on Moon Mountain 174 Recommended Books 186 Translators 188 海子 Hai Zi Born in Anhui in 1964, Hai Zi (the penname of Zha Haisheng, literally meaning “son of the sea”) was accepted into Peking University at the age of 15, and later taught philosophy and art theory at China University of Political Science and Law. -

Dancing at Lughnasa School of Theatre and Dance Illinois State University

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData School of Theatre and Dance Programs Theatre and Dance Fall 2013 Dancing At Lughnasa School of Theatre and Dance Illinois State University Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/sotdp Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation School of Theatre and Dance, "Dancing At Lughnasa" (2013). School of Theatre and Dance Programs. 46. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/sotdp/46 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Theatre and Dance at ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Theatre and Dance Programs by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. steve-o from MTV's Jackass October 5th Donnie Baker & Chick McGee from The Bob & Tom Show October 11th - 12th ,-----._-=,--::::a----, Ryan Stout from Chelsea Lately October 18th - 19th AI Jackson from Comedy Central October 24th - 26th Adam Ray from the hit movie "The Heat" November 14th - 16th • • f - I Drew lastings \ ~ ,, from The Bob and Tom Show ':. i ' November 22nd - 23rd • - ~ Jamie Kennedy from Malibu's Most Wanted December 5th - 7th 108 E Market Street Bloomington, IL I Phone: 309-287-7698 www.laughbloomington.com ONE E SCHOOL OF illlfi~~ ~ . Jllu,ouSrnrc u,,n••rnty AN if?\\Q\111~~ Center for the Performing Arts - Illinois State University November 1-2 & 5-9, 7:30 p.m. Matinee: November 3, 2:00 p.m. Dancing At Lughnasa by Brian Friel Director .............................................................................................................. -

Telling Me Lies Written by Linda Thompson,Linda Ronstadt,Betsy Cook, Dolly Parton B They Say a Woman's a Fool for Weeping A

Free Music resources from www.traditionalmusic.co.uk for personal education purposes only Telling Me Lies written by Linda Thompson,Linda Ronstadt,Betsy Cook, Dolly Parton B They say a woman's a fool for weeping A fool to break her own heart F# But I can't hold the secret I'm keeping E B I'm breaking apart B Can't seem to mind my own business Whatever I try turns out wrong F# I seem like my own false witness E B And I can't go on D Bm I cover my ears, I close my eyes B Bsus B Still hear your voice and it's telling me lies Telling me lies B You told me you needed my company And I believed in your flattering ways F# You told me you needed me forever E B Nearly gave you the rest of my days B Should've seen you for what you are Should never have come back for more F# Should've locked up all my silver E B Brought the key back to your door D Bm I cover my ears, I close my eyes B Bsus B Still hear your voice and it's telling me lies Telling me lies B You don't know what a chance is Until you have to seize one F# You don't know what a man is E B Until you have to please one B Don't put your life in the hands of a man B With a face for every season F# Don't waste your time in the arms of a man E B Who's no stranger to treason D Bm I cover my ears, I close my eyes Free Music resources from www.traditionalmusic.co.uk for personal education purposes only Free Music resources from www.traditionalmusic.co.uk for personal education purposes only B Bsus B Still hear your voice and it's telling me lies Telling me lies B I cover my ears, I close my eyes Still hear your voice and it's telling me lies Telling me lies From Parton*Ronstadt*Harris "Trio" Warner Brothers Records 1987 Copyright 1985 by Linda Thompson/Firesign Music Ltd. -

Past Productions

Past Productions 2017-18 2012-2013 2008-2009 A Doll’s House Born Yesterday The History Boys Robert Frost: This Verse Sleuth Deathtrap Business Peter Pan Les Misérables Disney’s The Little The Importance of Being The Year of Magical Mermaid Earnest Thinking Only Yesterday Race Laughter on the 23rd Disgraced No Sex Please, We're Floor Noises Off British The Glass Menagerie Nunsense Take Two 2016-17 Macbeth 2011-2012 2007-2008 A Christmas Carol Romeo and Juliet How the Other Half Trick or Treat Boeing-Boeing Loves Red Hot Lovers Annie Doubt Grounded Les Liaisons Beauty & the Beast Mamma Mia! Dangereuses The Price M. Butterfly Driving Miss Daisy 2015-16 Red The Elephant Man Our Town Chicago The Full Monty Mary Poppins Mad Love 2010-2011 2006-2007 Hound of the Amadeus Moon Over Buffalo Baskervilles The 39 Steps I Am My Own Wife The Mountaintop The Wizard of Oz Cats Living Together The Search for Signs of Dancing At Lughnasa Intelligent Life in the The Crucible 2014-15 Universe A Chorus Line A Christmas Carol The Real Thing Mid-Life! The Crisis Blithe Spirit The Rainmaker Musical Clybourne Park Evita Into the Woods 2005-2006 Orwell In America 2009-2010 Lend Me A Tenor Songs for a New World Hamlet A Number Parallel Lives Guys And Dolls 2013-14 The 25th Annual I Love You, You're Twelve Angry Men Putnam County Perfect, Now Change God of Carnage Spelling Bee The Lion in Winter White Christmas I Hate Hamlet Of Mice and Men Fox on the Fairway Damascus Cabaret Good People A Walk in the Woods Spitfire Grill Greater Tuna Past Productions 2004-2005 2000-2001 -

Karaoke Book

10 YEARS 3 DOORS DOWN 3OH!3 Beautiful Be Like That Follow Me Down (Duet w. Neon Hitch) Wasteland Behind Those Eyes My First Kiss (Solo w. Ke$ha) 10,000 MANIACS Better Life StarStrukk (Solo & Duet w. Katy Perry) Because The Night Citizen Soldier 3RD STRIKE Candy Everybody Wants Dangerous Game No Light These Are Days Duck & Run Redemption Trouble Me Every Time You Go 3RD TYME OUT 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL Going Down In Flames Raining In LA Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 3T 10CC Here Without You Anything Donna It's Not My Time Tease Me Dreadlock Holiday Kryptonite Why (w. Michael Jackson) I'm Mandy Fly Me Landing In London (w. Bob Seger) 4 NON BLONDES I'm Not In Love Let Me Be Myself What's Up Rubber Bullets Let Me Go What's Up (Acoustative) Things We Do For Love Life Of My Own 4 PM Wall Street Shuffle Live For Today Sukiyaki 110 DEGREES IN THE SHADE Loser 4 RUNNER Is It Really Me Road I'm On Cain's Blood 112 Smack Ripples Come See Me So I Need You That Was Him Cupid Ticket To Heaven 42ND STREET Dance With Me Train 42nd Street 4HIM It's Over Now When I'm Gone Basics Of Life Only You (w. Puff Daddy, Ma$e, Notorious When You're Young B.I.G.) 3 OF HEARTS For Future Generations Peaches & Cream Arizona Rain Measure Of A Man U Already Know Love Is Enough Sacred Hideaway 12 GAUGE 30 SECONDS TO MARS Where There Is Faith Dunkie Butt Closer To The Edge Who You Are 12 STONES Kill 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER Crash Rescue Me Amnesia Far Away 311 Don't Stop Way I Feel All Mixed Up Easier 1910 FRUITGUM CO. -

ISPCS 2011 201 Songs, 12.3 Hours, 1.45 GB

Page 1 of 6 ISPCS 2011 201 songs, 12.3 hours, 1.45 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 Boulevard Of Broken Dreams 2:56 Amy Winehouse's Jukebox Tony Bennett 2 Fly Me To The Moon 4:01 The Good Life Tony Bennett 3 The Good Life 2:18 The Good Life Tony Bennett 4 Thankful 4:49 Noël Josh Groban 5 Believe 4:18 The Polar Express (Soundtrack from th… Josh Groban 6 In The Middle Of An Island 2:11 The Good Life Tony Bennett 7 You Raise Me Up 4:52 Closer Josh Groban 8 The Reason 5:01 Let's Talk About Love Céline Dion 9 God Bless America 3:46 God Bless America Céline Dion 10 Paganini: Violin Concerto #1 In D, Op.… 7:04 Paganini: Violin Concerto #1; Tchaikov… Midori; Leonard Slatkin: London Symp… 11 I'm Alive 3:30 A New Day Has Come Céline Dion 12 The Prayer 4:29 Sogno (Non EU Version) Andrea Bocelli & Céline Dion 13 Vivaldi: Violin Concerto In E Flat, Op. 8… 3:41 Vivaldi: The Four Seasons, Etc. Gottfried Von Der Goltz; Andrew Lawr… 14 (I Want to Take You) Higher 4:44 I'm Back! Family & Friends Sly Stone & Jeff Beck 15 Vivaldi: Violin Concerto In G Minor, O… 6:24 Vivaldi: The Four Seasons, Etc. Gottfried Von Der Goltz; Andrew Lawr… 16 Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin) 4:56 I'm Back! Family & Friends Sly Stone & Johnny Winter 17 I Found Someone 3:44 Cher Cher 18 Strong Enough 3:41 Believe Cher 19 Trio in a, Op. -

Title "Stand by Your Man/There Ain't No Future In

TITLE "STAND BY YOUR MAN/THERE AIN'T NO FUTURE IN THIS" THREE DECADES OF ROMANCE IN COUNTRY MUSIC by S. DIANE WILLIAMS Presented to the American Culture Faculty at the University of Michigan-Flint in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Liberal Studies in American Culture Date 98 8AUGUST 15 988AUGUST Firs t Reader Second Reader "STAND BY YOUR MAN/THERE AIN'T NO FUTURE IN THIS" THREE DECADES OF ROMANCE IN COUNTRY MUSIC S. DIANE WILLIAMS AUGUST 15, 19SB TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface Introduction - "You Never Called Me By My Name" Page 1 Chapter 1 — "Would Jesus Wear A Rolen" Page 13 Chapter 2 - "You Ain’t Woman Enough To Take My Man./ Stand By Your Man"; Lorrtta Lynn and Tammy Wynette Page 38 Chapter 3 - "Think About Love/Happy Birthday Dear Heartache"; Dolly Parton and Barbara Mandrell Page 53 Chapter 4 - "Do Me With Love/Love Will Find Its Way To You"; Janie Frickie and Reba McEntire F'aqe 70 Chapter 5 - "Hello, Dari in"; Conpempory Male Vocalists Page 90 Conclusion - "If 017 Hank Could Only See Us Now" Page 117 Appendix A - Comparison Of Billboard Chart F'osi t i ons Appendix B - Country Music Industry Awards Appendix C - Index of Songs Works Consulted PREFACE I grew up just outside of Flint, Michigan, not a place generally considered the huh of country music activity. One of the many misconception about country music is that its audience is strictly southern and rural; my northern urban working class family listened exclusively to country music. As a teenager I was was more interested in Motown than Nashville, but by the time I reached my early thirties I had became a serious country music fan. -

KINGDOMS Family Guide

KINGDOMS Family Guide Welcome to IMMERSE The Bible Reading Experience Leading a family is arguably one of the most challenging tasks a person can undertake. And since families are the core unit in the church, their growth and development directly impacts the health of the communi- ties where they serve. The Immerse: Kingdoms Family Reading Guide is a resource designed to assist parents, guardians, and other family lead- ers to guide their families in the transformative Immerse experience. Planning Your Family Experience This family guide is essentially an abridged version of Immerse: King- doms. So it’s an excellent way for young readers in your family to par- ticipate in the Immerse experience without becoming overwhelmed. The readings are shorter than the readings in Immerse: Kingdoms and are always drawn from within a single day’s reading. This helps every- one in the family to stay together, whether reading from the family guide or the complete Kingdoms volume. Each daily Bible reading in the family guide is introduced by a short paragraph to orient young readers to what they are about to read. This paragraph will also help to connect the individual daily Scripture pas- sages to the big story revealed in the whole Bible. (This is an excellent tool for helping you guide your family discussions.) The family guide readings end with a feature called Thinking To- gether, created especially for young readers. These provide reflective statements and questions to help them think more deeply about the Scriptures they have read. (Thinking Together is also useful for guiding your family discussions.) The readings in the family guide are intended primarily for children i ii IMMERSE • KINGDOMS in grades 4 to 8. -

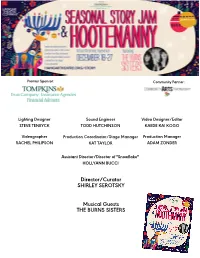

Hootenanny Insert

Premier Sponsor: Community Partner: Lighting Designer Sound Engineer Video Designer/Editor STEVE TENEYCK TODD HUTCHINSON KAEDE KAI KOGO Videographer Production Coordinator/Stage Manager Production Manager RACHEL PHILIPSON KAT TAYLOR ADAM ZONDER Assistant Director/Director of "Snowflake" HOLLYANN BUCCI Director/Curator SHIRLEY SEROTSKY Musical Guests THE BURNS SISTERS Start, pause, & rewind anytime! ORDER OF APPEARANCE 1. "Songs We Love” performed by The Burns Sisters. 2. “A Christmas Story" by Carrie Jane Thomas. Performed by Adara Alston. 3. "A Letter from Santa Claus" by Samuel Clemens (aka Mark Twain). Performed by Craig MacDonald with Katharyn Howd Machan, Jahmar Ortiz, and Sylvie Yntema. 4. “Golden Cradle” performed by The Burns Sisters 5. “Emmanuel” performed by The Burns Sisters. 6. "The Sermon in the Cradle" by W.E.B. DuBois. Performed by Robert Denzel Edwards. 7. "How to Spell the Name of God" by Ellen Orleans. Performed by Jennifer Herzog. 8. "Black Branches, White Moon" written and performed by Katharyn Howd Machan. 9. “Surrender” performed by The Burns Sisters. 10. "What are you Waiting For?" by Rebecca Barry. Performed by Marissa Accordino, K. Foula Dimopoulos, Kayla M. Lyon, and Gregg Miller. 11. "Food Shopping in Quarantine" by Sarah Jefferis. Performed by Sylvie Yntema. 12. "El Coquí Siempre Canta" written and performed by Sally Ramírez. 13.“Verde Luz” performed by Sally Ramirez with Special Appearance by Doug Robinson. 14. “Winter Wonderland” performed by The Burns Sisters. 15. “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” performed by The Burns Sisters. 16. “Tu Scendi Dalle Stelle” performed by The Burns Sisters. 17. "On Track" by Suzanne Snedeker. Performed by Susannah Berryman.