Brycheiniog Vol 43:44036 Brycheiniog 2005 27/4/16 12:23 Page 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Welsh Mountain Sheep Breeders' Association

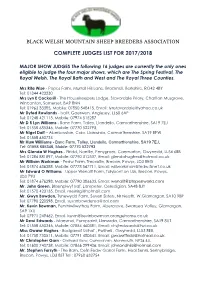

BLACK WELSH MOUNTAIN SHEEP BREEDERS ASSOCIATION COMPLETE JUDGES LIST FOR 2017/2018 MAJOR SHOW JUDGES The following 16 judges are currently the only ones eligible to judge the four major shows, which are The Spring Festival, The Royal Welsh, The Royal Bath and West and The Royal Three Counties. Mrs Rita Wise - Popes Farm, Murrell Hill Lane, Bracknell, Berkshire, RG42 4BY Tel: 01344 423230 Mrs Lyn E Cockerill - The Housekeepers Lodge, Stavordale Priory, Charlton Musgrove, Wincanton, Somerset, BA9 8NN Tel: 01963 33385, Mobile: 07850 548415, Email: [email protected] Mr Dyfed Rowlands - Isallt, Gaerwen, Anglesey, LL60 6AP Tel: 01248 421115, Mobile: 07974 515287 Mr D R Lyn Williams - Banc Farm, Talley, Llandeilo, Carmarthenshire, SA19 7EJ Tel: 01558 685346, Mobile: 07770 522793, Mr Nigel Daff – Aberbowlan, Caio, Llanwrda, Carmarthenshire, SA19 8PW Tel: 01558 650734 Mr Huw Williams - Banc Farm, Talley, Llandeilo, Carmarthenshire, SA19 7EJ, Tel: 01558 685346, Mobile: 07770 522793 Mrs Glenda W Hughes - Ffridd, Nantlle, Penygroes, Caernarfon, Gwynedd, LL54 6BB Tel: 01286 881897, Mobile: 07790 312537, Email: [email protected] Mr William Workman - Fedw Farm, Trecastle, Brecon, Powys, LD3 8RG Tel: 01874 636388, Mobile: 07778 567711, Email: [email protected] Mr Edward O Williams - Upper Wenallt Farm, Talybont on Usk, Brecon, Powys, LD3 7YU Tel: 01874 676298, Mobile: 07790 386633, Email: [email protected] Mr. John Green, Blaenplwyf Isaf, Lampeter, Ceredigion, SA48 8JY Tel: 01570 423135, Email. [email protected] Mr. Gwyn Bowden, Tynewydd Farm, Seven Sisters, Nr Neath, W.Glamorgan, SA10 9BP Tel: 07790 220598, Email. [email protected] Mr. Kevin Bowman, Penrhiwllwythau Farm, Abercrave, Swansea Valley, Glamorgan, SA9 1XU Tel: 07971 249462, Email. -

Residential Allocations Settlement Site Code Site Name Brecon B15

Residential Allocations Settlement Site Code Site Name Brecon B15 Cwmfalldau Fields (Under construction) CS28 Cwmfalldau fields extension CS93 Slwch House Field CS132 UDP allocation B17 opposite High School, North of Hospital (Mixed Use site of which 4.55ha is allocated for housing) DBR-BR-A Site located to the North of Camden Crescent and to the East of the Breconshire War Memorial Hospital DBR-BR-B Site located to the north of Cradoc Close and west of Maen-du Well Crickhowell DBR-CR-A Land above Televillage Hay-on-Wye DBR-HOW-A Land opposite The Meadows DBR-HOW-C Land adjacent to Fire Station DBR-HOW-K Land adjacent to Caemawr Cottages CS136 UDP allocation H6 Former Health Centre Sennybridge & Defynnog SALT 002/092 Land at Castle Farm CS138 Glannau Senni Talgarth T9 UDP allocation Land North of Doctors Surgery CS137 Hay Road (Mixed Use site of which 0.75ha is allocated for housing) Bwlch DBR-BCH-J Land adjacent to Bwlch Woods Crai CS43 Land SW of Gwalia CS42 Land at Crai Gilwern CS102 Lancaster Drive (Former UDP allocation GW2) Govilon CS39/69/70/ Land at Ty Clyd 88/89/99 Libanus DBR-LIB-E Land adjacent Pen y Fan Close Llanbedr DBR-LBD-A Land adjacent to St Peter’s Close Llanfihangel DBR-LC-D Land opposite Pen-y-Dre Farm Crucorney Llanigon DBR-LGN-D Land opposite Llanigon County Primary School Llanspyddid DBR-LPD-A Land off Heol St Cattwg Pencelli CS120 Land south of Ty Melys Pennorth DBR-PNT-D Land adjacent to Ambelside Ponsticill CS91 Land to the West of Pontsicill House, Pontsticill CS55 Land adjacent to Penygarn DBR-PSTC-C Land at end of Dan-y-Coed CS139 UDP allocation PST1 adj. -

Brycheiniog Vol 42:44036 Brycheiniog 2005 28/2/11 10:18 Page 1

68531_Brycheiniog_Vol_42:44036_Brycheiniog_2005 28/2/11 10:18 Page 1 BRYCHEINIOG Cyfnodolyn Cymdeithas Brycheiniog The Journal of the Brecknock Society CYFROL/VOLUME XLII 2011 Golygydd/Editor BRYNACH PARRI Cyhoeddwyr/Publishers CYMDEITHAS BRYCHEINIOG A CHYFEILLION YR AMGUEDDFA THE BRECKNOCK SOCIETY AND MUSEUM FRIENDS 68531_Brycheiniog_Vol_42:44036_Brycheiniog_2005 28/2/11 10:18 Page 2 CYMDEITHAS BRYCHEINIOG a CHYFEILLION YR AMGUEDDFA THE BRECKNOCK SOCIETY and MUSEUM FRIENDS SWYDDOGION/OFFICERS Llywydd/President Mr K. Jones Cadeirydd/Chairman Mr J. Gibbs Ysgrifennydd Anrhydeddus/Honorary Secretary Miss H. Gichard Aelodaeth/Membership Mrs S. Fawcett-Gandy Trysorydd/Treasurer Mr A. J. Bell Archwilydd/Auditor Mrs W. Camp Golygydd/Editor Mr Brynach Parri Golygydd Cynorthwyol/Assistant Editor Mr P. W. Jenkins Curadur Amgueddfa Brycheiniog/Curator of the Brecknock Museum Mr N. Blackamoor Pob Gohebiaeth: All Correspondence: Cymdeithas Brycheiniog, Brecknock Society, Amgueddfa Brycheiniog, Brecknock Museum, Rhodfa’r Capten, Captain’s Walk, Aberhonddu, Brecon, Powys LD3 7DS Powys LD3 7DS Ôl-rifynnau/Back numbers Mr Peter Jenkins Erthyglau a llyfrau am olygiaeth/Articles and books for review Mr Brynach Parri © Oni nodir fel arall, Cymdeithas Brycheiniog a Chyfeillion yr Amgueddfa piau hawlfraint yr erthyglau yn y rhifyn hwn © Except where otherwise noted, copyright of material published in this issue is vested in the Brecknock Society & Museum Friends 68531_Brycheiniog_Vol_42:44036_Brycheiniog_2005 28/2/11 10:18 Page 3 CYNNWYS/CONTENTS Swyddogion/Officers -

First Draft June 2016

BRECONBRECON CONSERVATION CONSERVATION AREAAREA APPRAISAL APPRAISAL Review Brecon Beacons National Park First Draft June 2016 1 BRECON CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Review of the Conservation Area Boundary 1 3 Community Involvement 5 4 The Planning Policy Context 5 5 Location and Context 6 6 Historic Development and Archaeology 7 7 Character Assessment 11 7.1 Quality of Place 11 7.2 Landscape Setting 12 7.3 Patterns of Use 13 7.4 Movement 14 7.5 Views and Vistas 15 7.6 Settlement Form 16 7.7 Character Areas 19 7.8 Scale 19 7.9 Landmark Buildings 20 7.10 Local Building Patterns 21 7.11 Materials 24 7.12 Architectural Detailing 25 7.13 Landscape/ streetscape 28 8 Important Local Buildings 33 9 Issues and Opportunities 34 10 Summary of Issues 39 11 Local Guidance and Management Proposals 40 12 Contact Details 42 13 Bibliography 42 14 Glossary of Architectural Terms 43 Appendices 2 1. Introduction 1.1 Section 69 of the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990 imposes a duty on Local Planning Authorities to determine from time to time which parts of their area are ‘areas of special architectural or historic interest, the character or appearance of which it is desirable to preserve or enhance’ and to designate these areas as conservation areas. The central area and historic suburbs of Brecon comprise one of four designated conservation areas in the National Park. The Brecon Conservation Area was designated by the National Park Authority on the 12th June 1970. 1.2 Planning authorities have a duty to protect these areas from development which would harm their special historic or architectural character and this is reflected in the policies contained in the National Park’s Local Development Plan. -

Herefordshire News Sheet

CONTENTS EDITORIAL ........................................................................................................................... 2 ARS OFFICERS AND COMMITTEE FOR 1986 ...................................................................... PROGRAMME APRIL-SEPTEMBER 1986 ........................................................................... 3 FIELD MEETING AT KINGS CAPLE, MARCH 10TH 1985 ..................................................... 3 FIELD MEETING, SUNDAY JULY 21ST 1985 ........................................................................ 5 BRECON GAER, ABERYSCIR, POWYS .............................................................................. 6 WORKERS’ EDUCATION ASSOCIATION AND THE LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETIES IN HEREFORDSHIRE – NINTH ANNUAL DAY SCHOOL ......................................................... 8 TWYN-Y-GAER, PENPONT ................................................................................................. 8 A CAREER IN RUINS … ...................................................................................................... 9 ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESEARCH SECTION 1985 ............................................................. 13 NEWS ITEM FROM THE CRASWALL GRANDMONTINE SOCIETY ................................. 14 THE HEREFORDSHIRE FIELD NAME SURVEY ............................................................... 14 FIELD NAMES COPIED FROM THE PARISH TITHE MAP ................................................ 16 HAN 45 Page 1 HEREFORDSHIRE ARCHAEOLOGICAL NEWS WOOLHOPE CLUB ARCHAEOLOGICAL -

Local Development Plan Written Statement

Brecon Beacons National Park Authority Local Development Plan 2007-2022 BRECON BEACONS NATIONAL PARK LOCAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN AS ADOPTED BY THE BRECON BEACONS NATIONAL PARK AUTHORITY 17TH DECEMBER 2013 i Brecon Beacons National Park Authority Local Development Plan 2007-2022 ii Brecon Beacons National Park Authority Local Development Plan 2007-2022 Contents 1 Introduction...................................................................................................................1 1.1 The Character of the Plan Area ..................................................................................1 1.2 How the Plan has been Prepared ..............................................................................................................1 1.3 The State of the Park: The Issues.............................................................................................................2 CHAPTER 2: THE VISION & OBJECTIVES FOR THE BRECON BEACONS NATIONAL PARK...................................................................................................................5 2.1 The National Park Management Plan Vision ...........................................................................................5 2.2 LDP Vision.......................................................................................................................................................6 2.3 Local Development Plan (LDP) Objectives.............................................................................................8 2.4 Environmental Capacity -

Wales.Nhs.Uk/Quality-And- Led Influenza Immunisation Programme in October 2018

POWYS TEACHING HEALTH BOARD ANNUAL QUALITY STATEMENT 2018/19 The Health and Care Strategy For Powys ‘at a glance’ We are developing a vision of the future of health and care in Powys… a leader in integrated rural health and care We aim to deliver START live age this vision throughout the lives of the people of Powys… fully We will support respiratory circulatory diseases diseases people to improve focus on mental their health and health problems d cancer wellbeing through… help and support tackling the big re equal pow people mo ys a communities Our priorities and on s pe focus s cialiscialis e t c r cacarre c u a o r s e e action will be honest support s r and upp treatments conversations p or wtreatments el t ne technologies how we h driven by clear use resources PLAN PLAN e equal principles… futur partners strengthstrengthss The future of workforcew rce futures l aa health and care tt i i community hubs g g i i d will improve d through… in partnership r e g e s g i o n a l c e n t r e Workforce Futures Innovative Environments Digital FirstTransforming in Partnership 2 Powys Teaching Health Board Annual Quality Statement 2019 Contents Introduction 4 Staying healthy 8 Safe care 14 Effective care 24 Dignified care 36 Timely care 42 Individual care 46 Staff and resources 54 Looking forward 62 Powys Teaching Health Board Annual Quality Statement 2019 3 INTRODUCTION From the CEO and Chair of PTHB From the Chair of the Quality and Safety We are pleased to present our Annual Quality Statement for 2018-2019. -

Brecknock Rare Plant Register Species of Interest That Are Not Native Or Archaeophyte S8/1

Brecknock Rare Plant Register Species of interest that are not native or archaeophyte S8/1 S8/1 Acanthus mollis 270m Status Local Welsh Red Data GB Red Data S42 National Sites Bear's-breech Troed yr arth Neophyte LR 1 Jun 2013 Acanthus mollis SO2112 Blackrock Mons: Llanelly: SSSI0733, SAC08 DB⁴ S8/2 Acer platanoides 260m Status Local Welsh Red Data GB Red Data S42 National Sites Norway Maple Masarnen Norwy 70m Neophyte NLS 18 Nov 2020 Acer platanoides SO0207 Nant Ffrwd, Merthyr Tydfil MT: Vaynor IR¹⁰ Oct 2020 Acer platanoides SO0012 Llwyn Onn (Mid) MT: Vaynor IR⁵ Apr 2020Acer platanoides SN9152 Celsau CFA11: Treflys JC¹ Mar 2020 Acer platanoides SO2314 Llanelly Mons: Llanelly JC¹ Feb 2019Acer platanoides SN9758 Cwm Crogau CFA11: Llanafanfawr DB¹ Oct 2018 Acer platanoides SO0924 Castle Farm CFA12: Talybont-On-Usk DB¹ Jan 2018 Acer platanoides SN9208 Afon Mellte CFA15: Ystradfellte: SSSI0451, DB⁴ SAC71, IPA139 Apr 2017Acer platanoides SN9665 Wernnewydd CFA09: Llanwrthwl DB¹ Jul 2016 Acer platanoides SO0627 Usk CFA12: Llanfrynach DB¹ Jun 2015Acer platanoides SN8411 Coelbren CFA15: Tawe-Uchaf DB² Sep 2014Acer platanoides SO1937 Tregoyd Villa field CFA13: Gwernyfed DB¹ Jan 2014 Acer platanoides SO2316 Cwrt y Gollen site CFA14: Grwyney… DB¹ Apr 2012 Acer platanoides SO0528 Brecon CFA12: Brecon DB¹⁷ 2008 Acer platanoides SO1223 Llansantffraed CFA12: Talybont-On-Usk DB² May 2002Acer platanoides SO1940 Below Little Ffordd-fawr CFA13: Llanigon DB² Apr 2002Acer platanoides SO2142 Hay on Wye CFA13: Llanigon DB² Jul 2000 Acer platanoides SO2821 Pont -

The Status of the Marsh Fritillary in Wales: 2016

The Status of the Marsh Fritillary in Wales: 2016 A lean year… If you visited a Marsh Fritillary site during the 2016 flight season you were probably struck by just how few butterflies were flying, even when the weather was fine – not just Marsh Fritillaries, but other species too. This was the case even on sites which held good numbers of larval webs in the autumn of 2015. It was all rather puzzling. But just how badly did the Marsh Fritillary fare in 2016? Keep reading to find out… Introduction The conservation of the Marsh Fritillary, one of the most rapidly declining butterflies in Europe, hinges on knowing where our core populations are, how they are faring and making sure that sites are well managed for the butterfly. Where are they? – Population status surveys To maintain an up-to-date picture of where our Welsh Marsh Fritillary populations are (distribution) Butterfly Conservation Wales (BCW) co-ordinates a Wales-wide programme of visits in which every population gets at least one survey visit every five years. As well as confirming presence or absence, these visits can also highlight concerns, such as management issues, that need following up. How strong are they? – Surveillance programme To assess how strong our Marsh Fritillary populations are, and how this changes over time, the Wales Marsh Fritillary Surveillance Programme was established in 2012 by BCW in partnership with Natural Resources Wales (NRW). Annual larval web counts of key populations (21 currently) are undertaken and used to calculate both site-level and Wales-wide trends. 1 Population Status Surveys The rolling programme of five-yearly site visits continued in 2016. -

From: Sharon Hughes

From: Sharon Hughes <[email protected]> Sent: 24 March 2020 19:39 Subject: Emergency child care for children under school age Good evening, We have been asked to circulate this information We would be grateful if the following message and link could be circulated to your parents. Many thanks Powys Childcare Team We are working to support families with their childcare needs to ensure the continuation of frontline services during the Covid-19 outbreak, and to provide care for vulnerable children. We are hoping to ensure that a limited number of our Childcare Providers remain open to provide care for these groups of children who are not yet of school age from Friday 27th March onwards. Where at all possible, children should stay at home. This cannot be over-emphasized. If your work is critical to the Covid-19 response or you work in one of the critical sectors listed below, and your child cannot stay at home, then your childcare will be prioritised: - Health and social care - Education and childcare - Key public services - Local and national government - Food and other necessary goods - Transport - Utilities, communication and financial services. From Friday 27th March, we are hoping to have childcare for children not of school age at the following locations: - Ystradgynlais - Brecon - Crickhowell - Llandrindod Wells - Newbridge - Llyswen - Newtown - Welshpool - Llanfyllin - Llanidloes The situation is being continually reviewed and there could be changes to provision, based on patterns of demand. Whilst we hope access to childcare will be provided to enable key workers to work during this critical period, we do need to keep the number of children in educational, childcare and play settings to the smallest number possible. -

Review of Community Boundaries in the County of Powys

LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR WALES REVIEW OF COMMUNITY BOUNDARIES IN THE COUNTY OF POWYS REPORT AND PROPOSALS LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR WALES REVIEW OF COMMUNITY BOUNDARIES IN THE COUNTY OF POWYS REPORT AND PROPOSALS 1. INTRODUCTION 2. POWYS COUNTY COUNCIL’S PROPOSALS 3. THE COMMISSION’S CONSIDERATION 4. PROCEDURE 5. PROPOSALS 6. CONSEQUENTIAL ARRANGEMENTS 7. RESPONSES TO THIS REPORT The Local Government Boundary Commission For Wales Caradog House 1-6 St Andrews Place CARDIFF CF10 3BE Tel Number: (029) 20395031 Fax Number: (029) 20395250 E-mail: [email protected] www.lgbc-wales.gov.uk Andrew Davies AM Minister for Social Justice and Public Service Delivery Welsh Assembly Government REVIEW OF COMMUNITY BOUNDARIES IN THE COUNTY OF POWYS REPORT AND PROPOSALS 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Powys County Council have conducted a review of the community boundaries and community electoral arrangements under Sections 55(2) and 57 (4) of the Local Government Act 1972 as amended by the Local Government (Wales) Act 1994 (the Act). In accordance with Section 55(2) of the Act Powys County Council submitted a report to the Commission detailing their proposals for changes to a number of community boundaries in their area (Appendix A). 1.2 We have considered Powys County Council’s report in accordance with Section 55(3) of the Act and submit the following report on the Council’s recommendations. 2. POWYS COUNTY COUNCIL’S PROPOSALS 2.1 Powys County Council’s proposals were submitted to the Commission on 7 November 2006 (Appendix A). The Commission have not received any representations about the proposals. -

WALES of IRELAND St John's Wales Wales and Prettytenby

Lerwick Kirkwall Dunnet Head Cape Wrath Duncansby Head Strathy Whiten Scrabster John O'Groats Rudha Rhobhanais Head Point (Butt of Lewis) Thurso Durness Melvich Castletown Port Nis (Port of Ness) Bettyhill Cellar Head Tongue Noss Head Wick Gallan Head Steornabhagh (Stornoway) Altnaharra Latheron Unapool Kinbrace Lochinver Helmsdale Hushinish Point Lairg Tairbeart Greenstone (Tarbert) Point Ullapool Rudha Reidh Bonar Bridge Tarbat Dornoch Ness Tain Gairloch Loch nam Madadh Lossiemouth (Lochmaddy) Alness Invergordon Cullen Fraserburgh Uig Cromarty Macduff Elgin Buckie Dingwall Banff Kinlochewe Garve Forres Nairn Achnasheen Torridon Keith Turriff Dunvegan Peterhead Portree Inverness Aberlour Huntly Lochcarron Dufftown Rudha Hallagro Stromeferry Ellon Cannich Grantown- Kyle of Lochalsh Drumnadrochit on-Spey Oldmeldrum Dornie Rhynie Kyleakin Loch Baghasdail Inverurie (Lochboisdale) Invermoriston Shiel Bridge Alford Aviemore Aberdeen Ardvasar Kingussie Invergarry Bagh a Chaisteil Newtonmore (Castlebay) Mallaig Laggan Ballater Banchory Braemar Spean Dalwhinnie Stonehaven Bridge Fort William Pitlochry Brechin Glencoe Montrose Tobermory Ballachulish Kirriemuir Forfar Aberfeldy Lochaline Portnacroish Blairgowrie Arbroath Craignure Dunkeld Coupar Angus Carnoustie Connel Killin Dundee Monifieth Oban Tayport Lochearnhead Newport Perth -on-Tay Fionnphort Crianlarich Crieff Bridge of Earn St Andrews SCOTLAND Auchterarder Auchtermuchty Cupar Inveraray Ladybank Fife Ness Callander Falkland Strachur Tarbet Dunblane Kinross Bridge Elie of Allan Glenrothes