MD4 Is Not One-Way

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fast Hashing and Stream Encryption with Panama

Fast Hashing and Stream Encryption with Panama Joan Daemen1 and Craig Clapp2 1 Banksys, Haachtesteenweg 1442, B-1130 Brussel, Belgium [email protected] 2 PictureTel Corporation, 100 Minuteman Rd., Andover, MA 01810, USA [email protected] Abstract. We present a cryptographic module that can be used both as a cryptographic hash function and as a stream cipher. High performance is achieved through a combination of low work-factor and a high degree of parallelism. Throughputs of 5.1 bits/cycle for the hashing mode and 4.7 bits/cycle for the stream cipher mode are demonstrated on a com- mercially available VLIW micro-processor. 1 Introduction Panama is a cryptographic module that can be used both as a cryptographic hash function and a stream cipher. It is designed to be very efficient in software implementations on 32-bit architectures. Its basic operations are on 32-bit words. The hashing state is updated by a parallel nonlinear transformation, the buffer operates as a linear feedback shift register, similar to that applied in the compression function of SHA [6]. Panama is largely based on the StepRightUp stream/hash module that was described in [4]. Panama has a low per-byte work factor while still claiming very high security. The price paid for this is a relatively high fixed computational overhead for every execution of the hash function. This makes the Panama hash function less suited for the hashing of messages shorter than the equivalent of a typewritten page. For the stream cipher it results in a relatively long initialization procedure. Hence, in applications where speed is critical, too frequent resynchronization should be avoided. -

Cryptanalysis of MD4

Cryptanalysis of MD4 Hans Dobbertin German Information Security Agency P. O. Box 20 03 63 D-53133 Bonn e-maih dobbert inQskom, rhein .de Abstract. In 1990 Rivest introduced the hash function MD4. Two years later RIPEMD, a European proposal, was designed as a stronger mode of MD4. Recently wc have found an attack against two of three rounds of RIPEMD. As we shall show in the present note, the methods developed to attack RIPEMD can be modified and supplemented such that it is possible to break the full MD4, while previously only partial attacks were known. An implementation of our attack allows to find collisions for MD4 in a few seconds on a PC. An example of a collision is given demonstrating that our attack is of practical relevance. 1 Introduction Rivest [7] introduced the hash function MD4 in 1990. The MD4 algorithm is defined as an iterative application of a three-round compress function. After an unpublished attack on the first two rounds of MD4 due to Merkle and an attack against the last two rounds by den Boer and Bosselaers [2], Rivest introduced the strengthened version MD5 [8]. The most important difference to MD4 is the adding of a fourth round. On the other hand the stronger mode RIPEMD [1] of MD4 was designed as a European proposal in 1992. The compress function of RIPEMD consists of two parallel lines of a modified version of the MD4 compress function. In [4] we have shown that if the first or the last round of its compress function is omitted, then RIPEMD is not collision-free. -

Performance Analysis of Cryptographic Hash Functions Suitable for Use in Blockchain

I. J. Computer Network and Information Security, 2021, 2, 1-15 Published Online April 2021 in MECS (http://www.mecs-press.org/) DOI: 10.5815/ijcnis.2021.02.01 Performance Analysis of Cryptographic Hash Functions Suitable for Use in Blockchain Alexandr Kuznetsov1 , Inna Oleshko2, Vladyslav Tymchenko3, Konstantin Lisitsky4, Mariia Rodinko5 and Andrii Kolhatin6 1,3,4,5,6 V. N. Karazin Kharkiv National University, Svobody sq., 4, Kharkiv, 61022, Ukraine E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] 2 Kharkiv National University of Radio Electronics, Nauky Ave. 14, Kharkiv, 61166, Ukraine E-mail: [email protected] Received: 30 June 2020; Accepted: 21 October 2020; Published: 08 April 2021 Abstract: A blockchain, or in other words a chain of transaction blocks, is a distributed database that maintains an ordered chain of blocks that reliably connect the information contained in them. Copies of chain blocks are usually stored on multiple computers and synchronized in accordance with the rules of building a chain of blocks, which provides secure and change-resistant storage of information. To build linked lists of blocks hashing is used. Hashing is a special cryptographic primitive that provides one-way, resistance to collisions and search for prototypes computation of hash value (hash or message digest). In this paper a comparative analysis of the performance of hashing algorithms that can be used in modern decentralized blockchain networks are conducted. Specifically, the hash performance on different desktop systems, the number of cycles per byte (Cycles/byte), the amount of hashed message per second (MB/s) and the hash rate (KHash/s) are investigated. -

Modified SHA1: a Hashing Solution to Secure Web Applications Through Login Authentication

36 International Journal of Communication Networks and Information Security (IJCNIS) Vol. 11, No. 1, April 2019 Modified SHA1: A Hashing Solution to Secure Web Applications through Login Authentication Esmael V. Maliberan Graduate Studies, Surigao del Sur State University, Philippines Abstract: The modified SHA1 algorithm has been developed by attack against the SHA-1 hash function, generating two expanding its hash value up to 1280 bits from the original size of different PDF files. The research study conducted by [9] 160 bit. This was done by allocating 32 buffer registers for presented a specific freestart identical pair for SHA-1, i.e. a variables A, B, C and D at 5 bytes each. The expansion was done by collision within its compression function. This was the first generating 4 buffer registers in every round inside the compression appropriate break of the SHA-1, extending all 80 out of 80 function for 8 times. Findings revealed that the hash value of the steps. This attack was performed for only 10 days of modified algorithm was not cracked or hacked during the experiment and testing using powerful online cracking tool, brute computation on a 64-GPU. Thus, SHA1 algorithm is not force and rainbow table such as Cracking Station and Rainbow anymore safe in login authentication and data transfer. For Crack and bruteforcer which are available online thus improved its this reason, there were enhancements and modifications security level compared to the original SHA1. being developed in the algorithm in order to solve these issues [10, 11]. [12] proposed a new approach to enhance Keywords: SHA1, hashing, client-server communication, MD5 algorithm combined with SHA compression function modified SHA1, hacking, brute force, rainbow table that produced a 256-bit hash code. -

On the Need for Multipermutations: Cryptanalysis of MD4 and SAFER

On the Need for Multipermutations: Cryptanalysis of MD4 and SAFER Serge Vaudenay* Ecole Normale Sup@rieure -- DMI 45, rue d'Ulm 75230 Paris Cedex 5 France Serge. Yaudenay@ens. fr Abstract. Cryptographic primitives are usually based on a network with boxes. At EUROCRYPT'94, Schnorr and the author of this pa- per claimed that all boxes should be multipermutations. Here, we inves- tigate a few combinatorial properties of multipermutations. We argue that boxes which fail to be multipermutations can open the way to un- suspected attacks. We illustrate this statement with two examples. Firstly, we show how to construct collisions to MD4 restricted to its first two rounds. This allows one to forge digests close to each other using the full compression function of MD4. Secondly, we show that variants of SAFER are subject to attack faster than exhaustive search in 6.1% cases. This attack can be implemented if we decrease the number of rounds from 6 to 4. In [18], multipermutatwns are introduced as formalization of perfect diffusion. The aim of this paper is to show that the concept of multipermutation is a basic tool in the design of dedicated cryptographic functions, as functions that do not realize perfect diffusion may be subject to some clever cryptanalysis in which the flow of information is controlled throughout the computation network. We give two cases of such an analysis. Firstly, we show how to build collisions for MD4 restricted to its first two rounds 2. MD4 is a three rounds hash function proposed by Rivest[17]. Den Boer and Bosselaers[2] have described an attack on MD4 restricted to its last two rounds. -

LNCS 3494, Pp

Cryptanalysis of the Hash Functions MD4 and RIPEMD Xiaoyun Wang1, Xuejia Lai2, Dengguo Feng3, Hui Chen1, and Xiuyuan Yu4 1 Shandong University, Jinan250100, China [email protected] 2 Shanghai Jiaotong University, Shanghai200052, China 3 Chinese Academy of Science China, Beijing100080, China 4 Huangzhou Teacher College, Hangzhou310012, China Abstract. MD4 is a hash function developed by Rivest in 1990. It serves as the basis for most of the dedicated hash functions such as MD5, SHAx, RIPEMD, and HAVAL. In 1996, Dobbertin showed how to find collisions of MD4 with complexity equivalent to 220 MD4 hash computations. In this paper, we present a new attack on MD4 which can find a collision with probability 2−2 to 2−6, and the complexity of finding a collision doesn’t exceed 28 MD4 hash operations. Built upon the collision search attack, we present a chosen-message pre-image attack on MD4 with com- plexity below 28. Furthermore, we show that for a weak message, we can find another message that produces the same hash value. The complex- ity is only a single MD4 computation, and a random message is a weak message with probability 2−122. The attack on MD4 can be directly applied to RIPEMD which has two parallel copies of MD4, and the complexity of finding a collision is about 218 RIPEMD hash operations. 1 Introduction MD4 [14] is an early-appeared hash function that is designed using basic arith- metic and Boolean operations that are readily available on modern computers. Such type of hash functions are often referred to as dedicated hash functions, and they are quite different from hash functions based on block ciphers. -

RIPEMD-160: a Strengthened Version of RIPEMD

RIPEMD-160: A Strengthened Version of RIPEMD Hans Dobbertin 1 Antoon Bosselaers 2 Bart Preneel 2. 1 German Information Security Agency P.O. Box 20 10 63, D-53133 Bonn, Germany dobbert in@skom, rheln, de 2 Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, ESAT-COSIC K. Mercierlaan 94, B-3001 Heverlee, Belgium {ant oon. bosselaers ,bart. preneel}@esat, kuleuven, ac .be Abstract. Cryptographic hash functions are an important tool in cryp- tography for applications such as digital fingerprinting of messages, mes- sage authentication, and key derivation. During the last five years, sev- eral fast software hash functions have been proposed; most of them are based on the design principles of Ron Rivest's MD4. One such proposal was RIPEMD, which was developed in the framework of the EU project RIPE (Race Integrity Primitives Evaluation). Because of recent progress in the cryptanalysis of these hash functions, we propose a new version of RIPEMD with a 160-bit result, as well as a plug-in substitute for RIPEMD with a 128-bit result. We also compare the software perfor- mance of several MD4-based algorithms, which is of independent inter- est. 1 Introduction and Background Hash functions are functions that map bitstrings of arbitrary finite length into strings of fixed length. Given h and an input x, computing h(x) must be easy. A one-way hash function must satisfy the following properties: - preimage resistance: it is computationally infeasible to find any input which hashes to any pre-specified output. - second prelmage resistance: it is computationally infeasible to find any second input which has the same output as any specified input. -

The Second Cryptographic Hash Workshop

Workshop Report The Second Cryptographic Hash Workshop University of California, Santa Barbara August 24-25, 2006 Report prepared by James Nechvatal and Shu-jen Chang Information Technology Laboratory, National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD 20899 Available online: http://csrc.nist.gov/groups/ST/hash/documents/SecondHashWshop_2006_Report.pdf 1. Introduction The Second Cryptographic Hash Workshop was held on Aug. 24-25, 2006, at University of California, Santa Barbara, in conjunction with Crypto 2006. 210 members of the global cryptographic community attended the workshop. The workshop was organized to encourage hash function research and discuss hash function development strategy. 2. Workshop Program The workshop program consisted of a day and a half of presentations of papers that were submitted to the workshop and panel discussion sessions. The main topics of the workshop included survey of hash function applications, new structures and designs of hash functions, cryptanalysis and attack tools, and development strategy of new hash functions. The program is available at http://csrc.nist.gov/groups/ST/hash/second_workshop.html . This report only briefly summarizes the presentations, because the above web site for the program includes links to the speakers' slides and papers. The main ideas of the discussion sessions, however, are described in considerable detail; in fact, the panelists and attendees are often paraphrased very closely, to minimize misinterpretation. Their statements are not necessarily presented in the order that they occurred, in order to organize them according to NIST's questions for each session. 3. Session Summary Session 1: Papers - New Structures of Hash Functions Session 1 included three talks dealing with new structures of hash functions. -

Public Key; Hash Functions

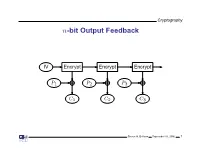

Cryptography n-bit Output Feedback IV Encrypt Encrypt Encrypt P1 P2 P3 C1 C2 C3 Steven M. Bellovin September 16, 2006 1 Cryptography Properties of Output Feedback Mode No error propagation • Active attacker can make controlled changes to plaintext • OFB is a form of stream cipher • Steven M. Bellovin September 16, 2006 2 Cryptography Counter Mode T T + 1 T + 2 Encrypt Encrypt Encrypt P1 P2 P3 C1 C2 C3 Steven M. Bellovin September 16, 2006 3 Cryptography Properties of Counter Mode Another form of stream cipher • Frequently split the counter into two sections: message number and • block number within the message Active attacker can make controlled changes to plaintext • Highly parallelizable; no linkage between stages • Vital that counter never repeat for any given key • Steven M. Bellovin September 16, 2006 4 Cryptography Which Mode for What Task? General file or packet encryption: CBC. • ☞Input must be padded to multiple of cipher block size Risk of byte or bit deletion: CFB or CFB • 8 1 Bit stream; noisy line and error propagation is undesirable: OFB • Very high-speed data: CTR • In most situations, an integrity check is needed • Steven M. Bellovin September 16, 2006 5 Cryptography Integrity Checks Actually, integrity checks are almost always needed • Frequently, attacks on integrity can be used to attack confidentiality • Usual solution: use separate integrity check along with encryption • Steven M. Bellovin September 16, 2006 6 Cryptography Combined Modes of Operation Integrity checks require a separate pass over the data • Such checks generally cannot be parallelized • For high-speed implementations, this is a considerable burden • Solution: combined modes such as Galois Counter Mode (GCM) or • Counter with CBC-MAC (CCM), which provide confidentiality and integrity protection in one pass Steven M. -

Applications of SAT Solvers in Cryptanalysis: Finding Weak Keys and Preimages

Journal on Satisfiability, Boolean Modeling and Computation 9 (2014) 1-25 Applications of SAT Solvers in Cryptanalysis: Finding Weak Keys and Preimages Fr´ed´ericLafitte [email protected] Department of Mathematics Royal Military Academy Belgium Jorge Nakahara Jr [email protected] Department of Computer Science Universit´eLibre de Bruxelles (ULB) Belgium Dirk Van Heule [email protected] Department of Mathematics Royal Military Academy Belgium Abstract This paper investigates the power of SAT solvers in cryptanalysis. The con- tributions are two-fold and are relevant to both theory and practice. First, we introduce an efficient, generic and automated method for generating SAT instances encoding a wide range of cryptographic computations. This method can be used to automate the first step of algebraic attacks, i.e. the generation of a system of algebraic equations. Second, we illustrate the limits of SAT solvers when attacking cryptographic algorithms, with the aim of finding weak keys in block ciphers and preimages in hash functions. SAT solvers allowed us to find, or prove the absence of, weak-key classes under both differential and linear attacks of full-round block ciphers based on the International Data Encryption Algorithm (IDEA), namely, WIDEA-n for n 2 f4; 8g, and MESH-64(8). In summary: (i) we have found sev- eral classes of weak keys for WIDEA-n and (ii) proved that a particular class of weak keys does not exist in MESH-64(8). SAT solvers provided answers to two complementary open problems (presented in Fast Software Encryption 2009): the existence and non-existence of such weak keys. -

Hash Function

3/24/2020 Hash and MAC Algorithms • Hash Functions – condense arbitrary size message to fixed size Cryptography – by processing message in blocks Hash Function – through some compression function – either custom or block cipher based Anand Ballabh Joshi Department of Mathematics • Message Authentication Code (MAC) University of Lucknow, Lucknow, India – fixed sized authenticator for some message – to provide authentication for message – by using block cipher mode or hash function Hash Algorithm Structure Secure Hash Algorithm • SHA originally designed by NIST & NSA in 1993 • was revised in 1995 as SHA-1 • US standard for use with DSA signature scheme – standard is FIPS 180-1 1995, also Internet RFC3174 – nb. the algorithm is SHA, the standard is SHS • based on design of MD4 with key differences • produces 160-bit hash values • recent 2005 results on security of SHA-1 have raised concerns on its use in future applications Revised Secure Hash Standard SHA-512 Overview • NIST issued revision FIPS 180-2 in 2002 • adds 3 additional versions of SHA – SHA-256, SHA-384, SHA-512 • designed for compatibility with increased security provided by the AES cipher • structure & detail is similar to SHA-1 • hence analysis should be similar • but security levels are rather higher 1 3/24/2020 SHA-512 Compression Function SHA-512 Round Function • heart of the algorithm • processing message in 1024-bit blocks • consists of 80 rounds – updating a 512-bit buffer – using a 64-bit value Wt derived from the current message block – and a round constant based on -

Secure Algorithms • Block and Stream Ciphers • DES, RC4 • Encryption Modes • Key Length • Cryptographic Hash Functions Encryption

Today • Secure algorithms • Block and Stream ciphers • DES, RC4 • Encryption modes • Key length • Cryptographic hash functions Encryption • Some cryptographic methods rely on the secrecy of the algorithms – Only historical interest – Not adequate for real-world applications • Generally, no algorithm that depends on its secrecy is secure • All modern algorithms – Use keys to control encryption and decryption – Cannot really be executed by humans • In theory, any cryptographic method with a key can be broken by trying all possible keys in sequence – Except One-time Pad Block and Stream ciphers • Block ciphers operate on blocks of plain-text and cipher-text. – Usually 64 or 128 bits – The same plain-text block will always encrypt to the same cipher-text block (same key of course) – DES, IDEA, AES (Rijndael), Blowfish, Twofish • Stream ciphers operate on streams of plain-text and cipher-text. – Usually 1 bit or 1 byte – The same bit or byte will encrypt to a different bit or byte – RC4, LFSRs, A5, SEAL Encryption modes • Encryption algorithms are seldom used directly, a cryptographic mode is used instead • A cryptographic mode usually combines – the basic cipher – some sort of feedback – some simple operations Electronic Codebook Mode • ECB - Electronic Codebook Mode • Simplest mode: no feedback - the same block always encrypt to the same cipher- text • Theoretically possible to create a codebook for each key; but for blocks of 64 bit the codebook needs 2^64 entries... • Statistical attacks possible CBC - Cipher Block Chaining • Chaining