Cleaning up East Potomac Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District of Columbia Inventory of Historic Sites Street Address Index

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA INVENTORY OF HISTORIC SITES STREET ADDRESS INDEX UPDATED TO OCTOBER 31, 2014 NUMBERED STREETS Half Street, SW 1360 ........................................................................................ Syphax School 1st Street, NE between East Capitol Street and Maryland Avenue ................ Supreme Court 100 block ................................................................................. Capitol Hill HD between Constitution Avenue and C Street, west side ............ Senate Office Building and M Street, southeast corner ................................................ Woodward & Lothrop Warehouse 1st Street, NW 320 .......................................................................................... Federal Home Loan Bank Board 2122 ........................................................................................ Samuel Gompers House 2400 ........................................................................................ Fire Alarm Headquarters between Bryant Street and Michigan Avenue ......................... McMillan Park Reservoir 1st Street, SE between East Capitol Street and Independence Avenue .......... Library of Congress between Independence Avenue and C Street, west side .......... House Office Building 300 block, even numbers ......................................................... Capitol Hill HD 400 through 500 blocks ........................................................... Capitol Hill HD 1st Street, SW 734 ......................................................................................... -

East-Download The

TIDAL BASIN TO MONUMENTS AND MUSEUMS Outlet Bridge TO FRANKLIN L’ENFANT DELANO THOMAS ROOSEVELT ! MEMORIAL JEFFERSON e ! ! George ! # # 14th STREET !!!!! Mason Park #! # Memorial MEMORIAL # W !# 7th STREET ! ! # Headquarters a ! te # ! r ## !# !# S # 395 ! t # !! re ^ !! e G STREET ! OHIO DRIVE t t ! ! # e I Street ! ! ! e ! ##! tr # ! !!! S # th !!# # 7 !!!!!! !! K Street Cuban ! Inlet# ! Friendship !!! CASE BRIDGE## SOUTHWEST Urn ! # M Bridge ! # a # ! # in !! ! W e A !! v ! e ! ! ! n ! ! u East Potomac !!! A e 395 ! !! !!!!! ^ ! Maintenance Yard !! !!! ! !! ! !! !!!! S WATERFRONT ! e ! !! v ! H 6 ri ! t ! D !# h e ! ! S ! y # I MAINE AVENUE Tourmobile e t George Mason k ! r ! c ! ! N e !! u ! e ! B East Potomac ! Memorial !!! !!! !! t !!!!! G Tennis Center WASHINGTON! !! CHANNEL I STREET ##!! !!!!! T !"!!!!!!! !# !!!! !! !"! !!!!!! O Area!! A Area B !!! ! !! !!!!!! N ! !! U.S. Park ! M S !! !! National Capital !!!!!#!!!! ! Police Region !!!! !!! O !! ! Headquarters Headquarters hi !! C !!!! o !!! ! D !!!!! !! Area C riv !!!!!!! !!!! e !!!!!! H !! !!!!! !!O !! !! !h ! A !! !!i ! ! !! !o! !!! Maine !!!D ! ! !!r !!!! # Lobsterman !!iv ! e !! N !!!!! !! Memorial ! ! !!" ! WATER STREET W !!! !! # ! ! N a ! ! ! t !! ! !! e !! ##! r !!!! #! !!! !! S ! ! !!!!!!! ! t !!! !! ! ! E r !!! ! !!! ! ! e !!!! ! !!!!!! !!! e ! #!! !! ! ! !!! t !!!!!#!! !!!!! BUCKEYE DRIVE Pool !! L OHIO #!DRIVE! !!!!! !!! #! !!! ! Lockers !!!## !! !!!!!!! !! !# !!!! ! ! ! ! !!!!! !!!! !! !!!! 395 !!! #!! East Potomac ! ! !! !!!!!!!!!!!! ! National Capital !!!! ! ! -

Potomac Flats.Pdf

Form 10-306 STATE: (Oct. 1972) NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NFS USE ONLY FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES ENTRY DATE (Type all entries - complete applicable sections) ———m COMMON: East and West Potomac Parks AND/OR HISTORIC: STREET AND NUMBER: area bounded by Constitution Avenue, 17th Street, Indepen dence Avenue, Washington Channel, Potomac River and Rock Creek Park CITY OR TOWN: CONGRESSIONAL ^ongressman Washington Walter E. Fauntroy, D.C. STATE: CODE COUNTY: District of Columbia 11 District of Columbia 001 CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC [X] District Q Building |XJ Public Public Acquisition: CD Occupied Yes: QSite CD Structure CD Private CD In Process I | Unoccupied I | Restricted CD Object CD Both I | Being Considered [ | Preservation work Qg) Unrestricted in progress LDNo PRESENT USE (Check One of More as Appropriate) I | Agricultural [XJ Government ffi Park 1X1 Transportation | | Commercial CD Industrial CD Private Residence CD Other (Specify) CD Educational CD Military [ | Religious I | Entertainment [~_[ Museum I | Scientific National Park Service, Department of the Interior REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: (If applicable) STREET AND NUMBER: National Capital Parks 1100 Ohio Drive, S.W. CITY OR TOWN: CODE Washington COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: None exists—parks are reclaimed land TITLE OF SURVEY: National Park Service survey in compliance with Executive Order 11593 DATE OF SURVEY: [29 Federal CD State CD County CD Local DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: 09 National Capital Parks STREET AND NUMBER: 1100 Ohio Drive, S.W. Cl TY OR TOWN: Washington District of Columbia 11 ©-©--- - - "- © - - _--_ -.- _---..-- . _ - B& Exc9\\en* [~~| Good- v'Q FVir - "^Q Deteriorated : - fH Ruins "-': - PI Unexposed : CONDWIOK -=."'-". -

Motorcoach Parking and Drop-Off/Pick-Up Locations

Motorcoach Parking and Drop-Off/Pick-Up Locations Number of Location Attraction Spaces Restrictions Cost Curbside Parking Locations 700-900 block Maine Avenue, SW Arena Stage/Waterfront 6 9:30am-4:00pm Mon-Fri: 4 hour limit Free 900-1200 block Maine Avenue, SW Arena Stage/Waterfront 4 No limit Free 1500 block Independence Avenue, Washington Monument 8 7:00am-6:30pm: 2 hour limit Free NW 200-400 block 15th Street, NW White House 5 7:00am-6:30pm: 2 hour limit Free 400 block New Jersey Avenue, NW Hyatt Regency 1 1 hour limit Free 3500 block Water St., NW Georgetown 4 No limit Free 1000 block 10th St, NW Souvenir City 1 7:00am-6:30pm: 1 hour limit Free Bus Parking Lot Locations $30/day Mon- Fri 6:00am-10:00pm in and out privileges $55 Sat-Sun and RFK Stadium, Lot 3, NE N/A 100 on weekdays only. Events Tel: (202) 608-1113 (Advance Purchase) or $60 day of. Union Station Parking Garage, NW N/A 20 7:00am-7:00pm Tel: (202) 430-2437 $20 per visit $20 up to 3 6:00am-6:00pm Monday-Friday Buzzard's Point Lot -1880 2nd St. SW N/A 80 hours/$50 per Tel: (202) 464-2900 day Hains Point/East Potomac Park, SW N/A 11 7:00am-6:00pm Free Off Street Parking at Tourist Sites Generally restricted to site visitors. Call Basilica of the National Shrine of the 400 Michigan Avenue, NE 100 for more information. Tel: (202) 526- Free Immaculate Conception 8300 Restricted to site visitors Tel: 1-800-967- 1411 W St, SE Frederick Douglass Memorial Home 3 Free 2283 Restricted to site visitors. -

Staff Recommendation

STAFF RECOMMENDATION NCPC File No. 7060 THE NATIONAL MALL NATIONAL MALL PLAN Washington, DC Submitted by the National Park Service November 23, 2010 Abstract The National Park Service has submitted the National Mall Plan for the management and stewardship of the land in its jurisdiction on the National Mall. The plan is a framework for future decision-making and implementation of physical improvements for the protection of the National Mall’s renowned natural and cultural resources, new visitor amenities and services, additional accommodations for First Amendment demonstrations and special events, better- linked circulation in a range of modes, accessibility throughout the Mall, additional opportunities for active and passive recreation, and improved visitor information and education. The National Park Service’s goal for the National Mall is that it be a model in sustainable urban park development, resource protection, and management. Commission Action Requested by Applicant Approval of the National Mall Plan, pursuant to 40 U.S.C. § 8722(b)(1) and (d)). Executive Director’s Recommendation The Commission: Approves the National Mall Plan, as shown on NCPC Map File No. 1.41(78.00)43205. Notes that: • The National Mall Plan is based on the Preferred Alternative presented and analyzed in the National Park Service’s Final Environmental Impact Statement, Record of Decision, and Section 106 Programmatic Agreement. NCPC File No. 7060 Page 2 • Additional compliance with the National Environmental Policy Act and the National Historic Preservation Act will be required for the development and implementation of many of the National Mall Plan’s proposed projects, and that the siting and design of individual projects are subject to the Commission’s review and approval. -

Comments Received

PARKS & OPEN SPACE ELEMENT (DRAFT RELEASE) LIST OF COMMENTS RECEIVED Notes on List of Comments: ⁃ This document lists all comments received on the Draft 2018 Parks & Open Space Element update during the public comment period. ⁃ Comments are listed in the following order o Comments from Federal Agencies & Institutions o Comments from Local & Regional Agencies o Comments from Interest Groups o Comments from Interested Individuals Comments from Federal Agencies & Institutions United States Department of the Interior NATIONAL PARK SERVICE National Capital Region 1100 Ohio Drive, S.W. IN REPLY REFER TO: Washington, D.C. 20242 May 14, 2018 Ms. Surina Singh National Capital Planning Commission 401 9th Street, NW, Suite 500N Washington, DC 20004 RE: Comprehensive Plan - Parks and Open Space Element Comments Dear Ms. Singh: Thank you for the opportunity to provide comments on the draft update of the Parks and Open Space Element of the Comprehensive Plan for the National Capital: Federal Elements. The National Park Service (NPS) understands that the Element establishes policies to protect and enhance the many federal parks and open spaces within the National Capital Region and that the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC) uses these policies to guide agency actions, including review of projects and preparation of long-range plans. Preservation and management of parks and open space are key to the NPS mission. The National Capital Region of the NPS consists of 40 park units and encompasses approximately 63,000 acres within the District of Columbia (DC), Maryland, Virginia and West Virginia. Our region includes a wide variety of park spaces that range from urban sites, such as the National Mall with all its monuments and Rock Creek Park to vast natural sites like Prince William Forest Park as well as a number of cultural sites like Antietam National Battlefield and Manassas National Battlefield Park. -

Potomac Park

46 MONUMENTAL CORE FRAMEWORK PLAN EDAW Enhance the Waterfront Experience POTOMAC PARK Potomac Park can be reimagined as a unique Washington destination: a prestigious location extending from the National Mall; a setting of extraordinary beauty and sweeping waterfront vistas; an opportunity for active uses and peaceful solitude; a resource with extensive acreage for multiple uses; and a shoreline that showcases environmental stewardship. Located at the edge of a dense urban center, Potomac Park should be an easily accessible place that provides opportunities for water-oriented recreation, commemoration, and celebration in a setting that preserves the scenic landscape. The park offers great potential to relieve pressure on the historic and fragile open space of the National Mall, a vulnerable resource that is increasingly overburdened with demands for large public gatherings, active sport fields, everyday recreation, and new memorials. Potomac Park and its shoreline should offer a range of activities for the enjoyment of all. Some areas should accommodate festivals, concerts, and competitive recreational activities, while other areas should be quiet and pastoral to support picnics under a tree, paddling on the river, and other leisure pastimes. The park should be connected with the region and with local neighborhoods. MONUMENTAL CORE FRAMEWORK PLAN 47 ENHANCE THE WATERFRONT EXPERIENCE POTOMAC PARK Context Potomac Park is a relatively recent addition to Ohio Drive parallels the walkway, provides vehicular Washington. In the early years of the city it was an access, and is used by bicyclists, runners, and skaters. area of tidal marshes. As upstream forests were cut The northern portion of the island includes 25 acres and agricultural activity increased, the Potomac occupied by the National Park Service’s regional River deposited greater amounts of silt around the headquarters, a park maintenance yard, offices for the developing city. -

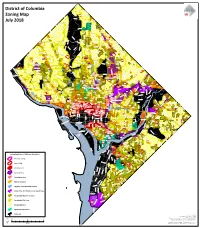

Pending Zoning Ac Ve PUD Pending PUD Campus Plans Downtown

East Beach Dr NW Beach North Parkway Portal District of Columbia Eastern Ave NW R-1-A Portal Dr NW Parkside Dr NW Kalmia Rd NW 97-16D Zoning Map 32nd St NW RA-1 12th St NW Wise Rd NW MU-4 R-1-B R-2 16th St NW R-2 76-3 Geranium St NW July 2018 Pinehurst Parkway Beech St NW Piney Branch Portal Aberfoyle Pl NW WR-1 RA-1 Alaska Ave NW WR-2 Takoma MU-4"M Worthington St NW WR-3 Dahlia St NW MU-4 WR-4 NC-2 R-1-A WR-6 RA-1 Utah Ave NW 31st Pl NW WR-6 MU-4 WR-5 RA-1 WR-7 Sherrill Dr NW WR-8 WR-3 MU-4 WR-5 Aspen St NW Nevada Ave NW Stephenson Pl NW Oregon Ave NW 30th St NW RA-2 4th St NW R-2 Van Buren St NW 2nd St NW Harlan Pl NW Pl Harlan R-1-B Broad Branch Rd NW Luzon Ave NW R-2 Pa�erson St NW Tewkesbury Pl NW 26th St NW R-1-B Chevy Tuckerman St NE Chase NW Pl 2nd Circle MU-3 Sheridan St NW Blair Rd NW Beach Dr NW R-3 MU-3 MU-3 MU-4 R-1-B Mckinley St NW Fort Circle Park 14th St NW Morrison St NW PDR-1 1st Pl NE 05-30 R-2 R-2 RA-1 MU-4 RA-4 Missouri Ave NW Peabody St NW Francis G. RA-1 04-06 Lega�on St NW Newlands Park RA-2 (Little Forest) Eastern Ave NE Morrow Dr NW RA-3 MU-7 Oglethorpe St NE Military Rd NW 2nd Pl NW 96-13 27th St NW Kanawha St NW Fort Slocum Friendship Heights Nicholson St NW Park MU-7 MU-5A R-2 R-2 "M Fort R-1-A NW St 9th Reno Rd NW Glover Rd NW Circle 85-20 R-3 Fort MU-4 R-2 NW St 29th Park MU-5A Circle Madison St NW MU-4 Park R-3 R-1-A RF-1 PDR-1 RA-2 R-8 RA-2 06-31A Fort Circle Park Linnean Ave NW R-16 MU-4 Rock Creek Longfellow St NW Kennedy St NE R-1-B RA-1 MU-4 RA-4 Ridge Rd NW Park & Piney MU-4 R-3 MU-4 Kennedy St NW -

Washington DC 5

307 See also separate subindexes for: 5 EATING P311 6 DRINKING & NIGHTLIFE P313 3 ENTERTAINMENT P313 7 SHOPPING P314 Index 2 SPORTS & ACTIVITIES P315 4 SLEEPING P315 9/11 270 can American Civil War arts 272-6, see also books, see also literature 18th Street NW 180 Memorial 191, 193, 27 architecture, individual history 258, 259, 268, 269 African American Civil War arts politics 269, 281 Museum 191 Atlas District 13, 145 Booth, John Wilkes A African American Heritage ATMs 295 155-6, 264 accommodations 15, Park 220 Aztec Gardens 106 241-54 breweries 13, 201 African American history 19 Adams-Morgan 252-3 Bureau of Engraving & air travel 288-9 Printing 28, 138 best for children 45 B Albert Einstein Planetarium B&O Railroad Museum bus travel 289, 290 Capitol Hill & Southeast 86 DC 246-7 (Baltimore) 229 Bush, George W 270 Albert Einstein statue 107 Downtown & Penn Babe Ruth Museum business hours 31, 34, Alexandria 339, see also Quarter 247-9 (Baltimore) 229 38, 293 northern Virginia Dupont Circle & Kalorama Baltimore 228-31 drinking & nightlife 223 249-52 Baltimore Maritime Museum entertainment 224 C Georgetown 246 (Baltimore) 228 C&O Canal & Towpath 117, food 222-3 northern Virginia 254 Barry, Marion 270, 282 118, 117 sights 219-21 tipping 242 Bartholdi Fountain 92 C&O Canal Gatehouse 96 Alexandria Archaeology U Street, Columbia baseball 149, 229 Camden Yards (Baltimore) Museum 219 Heights & Northeast Basilica of the National 229 Alexandria Black History 253 Shrine of the Immaculate canoeing, see kayaking Museum 220 Conception 194 Upper Northwest -

District of Columbia Inventory of Historic Sites Street Address Index

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA INVENTORY OF HISTORIC SITES STREET ADDRESS INDEX UPDATED TO JANUARY 31, 2015 NUMBERED STREETS Half Street, SW 1360 ........................................................................................ Syphax School 1st Street, NE between East Capitol Street and Maryland Avenue ................ Supreme Court 100 block ................................................................................. Capitol Hill HD between Constitution Avenue and C Street, west side ............ Senate Office Building and M Street, southeast corner ................................................ Woodward & Lothrop Warehouse 1st Street, NW 320 .......................................................................................... Federal Home Loan Bank Board 2122 ........................................................................................ Samuel Gompers House 2400 ........................................................................................ Fire Alarm Headquarters between Bryant Street and Michigan Avenue ......................... McMillan Park Reservoir 1st Street, SE between East Capitol Street and Independence Avenue .......... Library of Congress between Independence Avenue and C Street, west side .......... House Office Building 300 block, even numbers ......................................................... Capitol Hill HD 400 through 500 blocks ........................................................... Capitol Hill HD 1st Street, SW 734 ......................................................................................... -

WASHINGTON, D.C. Our Land, Our Water, Our Heritage

WASHINGTON, D.C. Our Land, Our Water, Our Heritage . LWCF Funded Places in Washington, D.C. LWCF Success in Washington, D.C. The Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) has provided funding to help protect some of Washington, D.C.’s most special places and ensure Federal Program recreational access for hiking, cycling, fishing and other outdoor Ford’s Theatre NHS activities. Washington, D.C. has received approximately $18 million in FDR Memorial LWCF funding over the past five decades, protecting places such as the National Capital Parks-East Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial, Mary McLeod Bethune NHS, and Mary McLeod Bethune NHS National Capital Parks-East. Federal Total $4,200,000 LWCF state assistance grants have further supported hundreds of projects across Washington, D.C.’s local parks including Mitchell Park State Program Playground, Randall Recreation Center, and the East Potomac Park Total State Grants $13,800,000 Swimming Pool. Total $18,000,000 Kenilworth Park and Aquatic Gardens Visitors and residents of Washington, D.C. experience the natural habitat of the area at the beautifully preserved Kenilworth Aquatic Gardens. This wetland helps mitigate pollution, reduces flood damage, and alleviates risks from climate change. As part of the National Capital Parks East, this park which has hiking trails, boardwalks, and comprehensive environmental education resources, has received a portion of the $2.5 million of LWCF awarded to the District’s network of parks. In addition to many events over the year, members of the D.C. Garden Club plant thousands of lotus each spring, a one-of-a-kind spectacle that draws visitors from across town and around the world. -

Commemorative Works Catalog

DRAFT Commemorative Works by Proposed Theme for Public Comment February 18, 2010 Note: This database is part of a joint study, Washington as Commemoration, by the National Capital Planning Commission and the National Park Service. Contact Lucy Kempf (NCPC) for more information: 202-482-7257 or [email protected]. CURRENT DATABASE This DRAFT working database includes major and many minor statues, monuments, memorials, plaques, landscapes, and gardens located on federal land in Washington, DC. Most are located on National Park Service lands and were established by separate acts of Congress. The authorization law is available upon request. The database can be mapped in GIS for spatial analysis. Many other works contribute to the capital's commemorative landscape. A Supplementary Database, found at the end of this list, includes selected works: -- Within interior courtyards of federal buildings; -- On federal land in the National Capital Region; -- Within cemeteries; -- On District of Columbia lands, private land, and land outside of embassies; -- On land belonging to universities and religious institutions -- That were authorized but never built Explanation of Database Fields: A. Lists the subject of commemoration (person, event, group, concept, etc.) and the title of the work. Alphabetized by Major Themes ("Achievement…", "America…," etc.). B. Provides address or other location information, such as building or park name. C. Descriptions of subject may include details surrounding the commemorated event or the contributions of the group or individual being commemorated. The purpose may include information about why the commemoration was established, such as a symbolic gesture or event. D. Identifies the type of land where the commemoration is located such as public, private, religious, academic; federal/local; and management agency.