Achilles Heel in Emergency Communications: the Deplorable Policies and Practices Pertaining to Non English Speaking Populations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Awm July Newsletter 2011

Your Austin Connection Contents… Media Program Local Community Date Career Corporate Your new 2011-2012 AWM Austin board is focused, determined, and most of all EXCITED to make this the best year yet for ALL supporters of women in the Austin media! Be sure to check our DATE CONNECTION page for upcoming events & save-the-dates. An Austin A.W.M. Publication JULY 2011/VOLUME 99 Schedule at a Glance Wednesday, Aug. 10 8 am Annual Golf Tournament 12 noon REGISTRATION OPENS 1– 6:30p Seminars Texas Association of 6:30 pm REGISTRATION CLOSES Broadcasters/Society of 6:30 pm Opening Reception Broadcast Engineers 7:30 pm Annual Pioneer Club Banquet 58th Annual Convention Thursday, Aug. 11 & Trade Show 7 am REGISTRATION OPENS Community Service Awards August 10-11, 2011 7:30 am Renaissance Austin Hotel Breakfast 8a – 6 p Seminars The event is the largest state 9a – 5 p Trade Show Open Walk-Around Lunch in broadcast association convention 11a – 1 p in the nation, with 1,100+ annual Exhibit Hall registrants. 2:30 pm Annual Business Meeting 7 pm REGISTRATION CLOSES Questions? 7 pm Chairman’s Reception Call (512) 322-9944. 7:30 pm Annual Awards Gala Full Schedule & Registration Information at www.tab.org. For more information visit http://www.awmaustin.org/. THE TIME IS NOW TO BE A PART OF AWM AUSTIN! $75 National Membership $60 Local Austin Chapter Membership $30 Student Membership For more information, please e-mail [email protected] or visit http://awmaustin.org/membership/. AUSTIN ALLIANCE FOR WOMEN IN MEDIA… LIKE US! There’s lots going on in Austin media …so remember to LIKE us to be in the know! Check out our photos and be sure to tag all your friends. -

Lana-Del-Golazo-Bmf-July-2021.Pdf

Reglas Oficiales 1. Nombre de la Promoción: ¡La Lana Del Golazo! NO ES NECESARIA LA COMPRA O EL PAGO ALGUNO PARA PARTICIPAR O GANAR. LA COMPRA NO MEJORARÁ SUS OPORTUNIDADES DE GANAR. INVALIDO DONDE PROHIBIDO. 1. Nombre y dirección del Patrocinador: Las estaciones de Univision Radio Inc., en; Los Ángeles, Inc., d/b/a KSCA 101.9FM con oficinas en 5999 Center Drive, Los Ángeles, CA 90045; San Francisco, Inc., d/b/a KSOL/KSQL 98.9 & 99.1FM con oficinas en 1940 Zanker Rd, San Jose, CA 95112; Phoenix, Inc d/b/a KHOT 105.9FM con oficinas en 6006 South 30th Street Phoenix, AZ 85042; Las Vegas, Inc., d/b/a KISF 103.5FM con oficinas en 6767 W. Tropicana Ave, ste 102 Las Vegas, NV 89103; Fresno, Inc d/b/a KOND 107.5FM con oficinas en 601 West Univision Plaza Fresno, CA 93704; Dallas, Inc., d/b/a KLNO 94.1FM con oficinas en 2323 Bryan St suite 1900, Dallas, TX 75201; Chicago, Inc., d/b/a WOJO 105.1FM con oficinas en 541 N. Fairbanks Ct, Ste 1100 Chicago, IL 60611; NM 87110;; Austin, Inc., d/b/a KLQB 104.3 FM con oficinas en 2233 W. North Loop Blvd, Austin, TX 78756 y las afiliadas siguientes: Nashville, Inc, d/b/a WNVL 105.1FM con oficinas en 3955 Nolensville Pike, Nashville, TN 37211; Greenville, Inc d/b/a WTOB 103.9 FM y 105.7 FM, 910AM con oficinas en 225 S. Pleasantburg Drive STE B-3 Greenville, SC 29607; Denver, Inc, d/b/a KBNO 97.7FM and 1280 AM con oficinas en777 Grant ST. -

Austin Hispanic People in the News

Free Gratis Volume 6 Number 8 LaLa VVozoz A Bilingual PublicationLaLaLa VVVozozoz August, 2011 www.lavoznewspapers.com (512) 944-4123 In this issue Austin Hispanic People in the News El Centro at Texas State Media OverviewQÈH 3FDFUBTGÈDJMFTQBSBUPSUJUBTEFMJDJPTBTBUVHVTUP -0$"- University $0.*%" %&+6/*0"-%&+6/*0%& Remembering "WBO[BQSPZFDUP BOUJJONJHSBOUF -FZQPESÓBSFRVFSJSRVF QPMJDÓBTQJEBOFTUBUVTQÈH Richard Chavez NJHSBUPSJP %&1035&4 &WFOUPEFCPYFP The Seedling & SJOEFIPNFOBKFBM &--&("%0% DBNQFØONVOEJBM QÈH ZIÏSPFMPDBM Foundation $PQB0SPTJHVF A&-."5"%03 DPOFMJNJOBDJPOFT .ÏYJDP $PTUB3JDB &%6$"$*»/ &TUBEPT6OJEPTMMFHBOB DVBSUPTEFmOBM QÈH $FMFCSBBUVQBQÓFOTVEÓB QÈH -BJNQPSUBODJBEFRVFFMMPTQBSUJDJQFO &7&/504 FOMBFEVDBDJØOEFTVTIJKPT )03»4$0104 Radio Stations '".*-*" /05*$*"4 $0.6/*%"% %&1035&4 Hispanic Newspapers Hispanic Television Stations Central Texas Diversity Summit En las palabras hay poder Calender of Events Page 2 La Voz de Austin - August, 2011 Travis High School Anuncia su Matriculación La matrícula está abierta a estudiantes nuevo a AISD o estudiantes actuales de AISD que ha movido o ha transferido durante el verano. Si usted tiene cualquier pregunta llama por favor 512-414-2527. ¡Favorecemos a todos estudiantes y las familias afectaron para aprovecharse de esta oportunidad maravillosa para estar listo para el Nuevo año escolar próximo y emocionante! LOS BENEFICIOS DE MATRICULA TEMPRANA: AISD Registration Requirements Todos estudiantes nuevo a Austin ISD: · Estudiante está listo para el año escolar en el primer día! deben proporcionar -

The Future of Sea Mines in the Indo-Pacific

Issue 18, 2020 BREACHING THE SURFACE: THE FUTURE OF SEA MINES IN THE INDO-PACIFIC Alia Huberman, The Australian National Internships Program Issue 18, 2020 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report argues that several dynamics of the coming few decades in the Indo-Pacific will see naval mines used once again in the region. It suggests they will form the basis of anti-access strategies for some Indo-Pacific states in a way that will be deeply transformative for the region’s strategic balance and for which Australia is thoroughly unprepared. It seeks to draw attention to the often- underappreciated nature of sea mines as a uniquely powerful strategic tool, offering the user an unparalleled asymmetric ability to engage high-value enemy targets while posing a minimal-risk, low- expense, and continuous threat. In the increasingly contested strategic environment of the contemporary Indo-Pacific - a region in which the threats to free navigation and the maritime economy are existential ones - there is considerable appetite for anti-access and sea denial weapons as defensive, offensive, and coercive tools. Naval strategists must,, prepare for the resurgence of mine warfare in the Indo-Pacific, and for the grand-scale and rapid timeline in which it can transform an operational environment. This report first seeks to collate and outline those characteristics of sea mines and of their interaction with an operational environment that make them attractive for use. It then discusses the states most likely to employ mine warfare and the different scenarios in which they might do so, presenting five individual contingencies: China, Taiwan, North Korea, non-state actors, and Southeast Asian states. -

Chlorine: the Achilles Heel?

Chlorine: the Achilles Heel? John McNabb Cohasset Water Commissioner Cohasset, Massachusetts Water Security Congress Washington DC, April 8-10, 2008 1 Cohasset Water Dept. • I have been an elected Water Commissioner in Cohasset, Mass. Since 1997. Just reelected to 5th term. • We serve about 7,000 residents, 2,500 accounts, 400 hydrants, 750 valves, 2 tanks, 1 wellfield, 2 reservoirs. Lily Pond Water Treatment Plant uses conventional filtration, fluoridation, and chlorination. • I am not an “expert” on water infrastructure security; this is more an essay than a formal analysis. • From 1999-Jan. 2009 I worked for Clean Water Action. • Now I work in IT security, where responsible disclosure of potential threats, not ‘security by obscurity” is the preferred method. 2 Cohasset – security measures • Vulnerability assessment as required • Fences & gates • Locks • Alarms, especially on storage tanks • Motion detectors • Video surveillance • Isolate SCADA from the internet • We think we’ve done everything that is reasonably necessary. 3 Water system interdependencies • But, the protection of our water system depends also on may factors outside of our control • The treatment chemicals we use is a critical factor. 4 Chlorine - Positives • Chlorination of drinking water is one of the top 5 engineering accomplishments of the modern age. • Chlorination of the US drinking water supply wiped out typhoid and cholera, and reduced the overall mortality rate in the US. 5 Chlorine - Negatives • Chlorine is very toxic, used as weapon in WWI. • Disinfection Byproducts (DPBs) • Occupational exposure on the job • Chlorine explosions on site at the plant • Terrorist use of chlorine as an explosive • Vector of attack? 6 Chlorine Explosions & Accidents • The Chlorine Institute estimates a chlorine tanker terrorist attack could release a toxic cloud up to 15 miles. -

Stations Monitored

Stations Monitored 10/01/2019 Format Call Letters Market Station Name Adult Contemporary WHBC-FM AKRON, OH MIX 94.1 Adult Contemporary WKDD-FM AKRON, OH 98.1 WKDD Adult Contemporary WRVE-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 99.5 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WYJB-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY B95.5 Adult Contemporary KDRF-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KMGA-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 99.5 MAGIC FM Adult Contemporary KPEK-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 100.3 THE PEAK Adult Contemporary WLEV-FM ALLENTOWN-BETHLEHEM, PA 100.7 WLEV Adult Contemporary KMVN-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MOViN 105.7 Adult Contemporary KMXS-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MIX 103.1 Adult Contemporary WOXL-FS ASHEVILLE, NC MIX 96.5 Adult Contemporary WSB-FM ATLANTA, GA B98.5 Adult Contemporary WSTR-FM ATLANTA, GA STAR 94.1 Adult Contemporary WFPG-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ LITE ROCK 96.9 Adult Contemporary WSJO-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ SOJO 104.9 Adult Contemporary KAMX-FM AUSTIN, TX MIX 94.7 Adult Contemporary KBPA-FM AUSTIN, TX 103.5 BOB FM Adult Contemporary KKMJ-FM AUSTIN, TX MAJIC 95.5 Adult Contemporary WLIF-FM BALTIMORE, MD TODAY'S 101.9 Adult Contemporary WQSR-FM BALTIMORE, MD 102.7 JACK FM Adult Contemporary WWMX-FM BALTIMORE, MD MIX 106.5 Adult Contemporary KRVE-FM BATON ROUGE, LA 96.1 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WMJY-FS BILOXI-GULFPORT-PASCAGOULA, MS MAGIC 93.7 Adult Contemporary WMJJ-FM BIRMINGHAM, AL MAGIC 96 Adult Contemporary KCIX-FM BOISE, ID MIX 106 Adult Contemporary KXLT-FM BOISE, ID LITE 107.9 Adult Contemporary WMJX-FM BOSTON, MA MAGIC 106.7 Adult Contemporary WWBX-FM -

Radio Market Definition at This Juncture

February 12, 2003 Notice of Ex Parte Communication Ms. Marlene H. Dortch Secretary Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street, S.W. Washington, DC 20554 Re: MM Docket No. 00-244 Dear Ms. Dortch: Yesterday, Jack Goodman, Karen Kirsch and the undersigned of NAB; Brian Madden of Leventhal, Senter & Lerman; and Greg Masters and Chris Robbins of Wiley Rein & Fielding met with Susan Eid and Alex Johns to discuss the definition of radio markets. We made the following points: · Due to the scattered location and widely varying signal strength of radio stations, any method of defining radio markets will produce a certain number of anomalies. The current market definition method has produced only a small number of anomalies in comparison to the large number of radio transactions since 1996. The current method is also stable in operation, well understood by the industry, and accurately identifies the stations that potentially compete against each other for listeners and advertisers. Adopting a revised market definition will only create a different and unpredictable set of anomalies. · The Commission lacks the authority to alter its radio market definition at this juncture. Because Congress in 1996 addressed local radio ownership limits and did not change the Commission’s well-established interpretation of what constitutes a radio market, then that interpretation should, under existing court precedent, be regarded as the interpretation intended by Congress. Certainly the Commission should not alter its market definition to cut back on the level of local radio consolidation expressly approved by Congress in 1996. · The Commission should not adopt Arbitron radio markets, for a variety of reasons. -

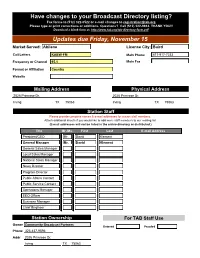

TAB Records-Stations (TABSERVER08)

Have changes to your Broadcast Directory listing? Fax forms to (512) 322-0522 or e-mail changes to [email protected] Please type or print corrections or additions. Questions? Call (512) 322-9944. THANK YOU!! Download a blank form at: http://www.tab.org/tab-directory-form.pdf Updates due Friday, November 15 Market Served: Abilene License City: Baird Call Letters KABW-FM Main Phone 817-917-7233 Frequency or Channel 95.1 Main Fax Format or Affiliation Country Website Mailing Address Physical Address 2026 Primrose Dr. 2026 Primrose Dr. Irving TX 75063 Irving TX 75063 Station Staff Please provide complete names & e-mail addresses for station staff members. Attach additional sheets if you would like to add more staff members to our mailing list. (E-mail addresses will not be listed in the online directory or distributed.) Title Mr./Ms. First Last E-mail Address President/CEO Mr. David Klement General Manager Mr. David Klement General Sales Manager Local Sales Manager National Sales Manager News Director Program Director Public Affairs Contact Public Service Contact Operations Manager EEO Officer Business Manager Chief Engineer Station Ownership For TAB Staff Use Owner Community Broadcast Partners Entered Proofed Phone 325-437-9596 Addr 2026 Primrose Dr. Irving TX 75063 Have changes to your Broadcast Directory listing? Fax forms to (512) 322-0522 or e-mail changes to [email protected] Please type or print corrections or additions. Questions? Call (512) 322-9944. THANK YOU!! Download a blank form at: http://www.tab.org/tab-directory-form.pdf Updates due Friday, November 15 Market Served: Abilene License City: Abilene Call Letters KACU-FM Main Phone 325-674-2441 Frequency or Channel 89.7 Main Fax 325-674-2417 Format or Affiliation Soft AC, News (NPR) Website www.kacu.org Mailing Address Physical Address ACU Station 1600 Campus Court Abilene TX 79699-7820 Abilene TX 79601 Station Staff Please provide complete names & e-mail addresses for station staff members. -

Austin Hispanic Turnout Data Pamphlet Download

HISPANIC VOTER TURNOUT HISPANIC VOTERS IN AUSTIN ARE Registered Voters ENERGIZED Austin Hispanic voter turnout reached 68.7% in Turnout 58.6% 2020. Total Arizona Hispanic voter turnout In 2018 Of Austin was 60.2%. Hispanics voted 68.7% during the 2020 Hispanic voter turnout in 2020 was driven by Turnout Elections vs 60.8% younger voters 18-34. In 2016 Growth in number of Hispanic early voters outpaced Non-Hispanics. TURNOUT GROWTH 179,597 Austin Hispanics voted during the 2020 elections vs. SPANISH IS THE LANGUAGE OF 131,392 in 2018 ENGAGEMENT FOR HISPANIC VOTERS 123,256 in 2016 IN AUSTIN Hispanic voters are most effectively reached and persuaded in-language and in-culture. HISPANIC Spanish language ads deliver greater message EARLY VOTERS & VOTE BY MAIL impact In Austin from 2016 to 2020 grew VOTERS IN vs. 50% Non-Hispanic AUSTIN +76% UNIVISION IS THE GATEWAY TO 2020 Hispanic EV + VBM: 155,912 2018 Hispanic EV + VBM: 95,216 HISPANIC VOTERS IN AUSTIN 2016 Hispanic EV + VBM: 88,396 The New Majority Makers Univision is the best connection to reach Hispanic YOUNG VOTERS voters with your message. Turnout Growth Among Hispanic Voters 18-34 from 2018 to 2020 Our capabilities give campaigns the winning advantage +41% Austin Hispanic Voter 18-34 Turnout vs. 60,078 42,647 36,650 CONTACT US AT [email protected] 2020 2018 2016 +36% Austin Non-Hispanics voter turnout growth in 2020 vs 2018 Source: L2 Registered Voter File, retrieved June 2021. ABOUT UNIVISION AUSTIN GROWTH OF HISPANIC VOTERS IS TV and Radio Properties SIGNIFICANTLY HIGHER THAN NON-HISPANIC KAKW Univision 62 Serving the Austin DMA’s growing market, provides Voter Turnout Growth 2018-2020 Hispanic programming and community support that is aimed at Hispanic Americans in the market. -

List of Radio Stations in Texas

Not logged in Talk Contributions Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Search Wikipedia List of radio stations in Texas From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Main page The following is a list of FCC-licensed AM and FM radio stations in the U.S. state of Texas, which Contents can be sorted by their call signs, broadcast frequencies, cities of license, licensees, or Featured content programming formats. Current events Random article Contents [hide] Donate to Wikipedia 1 List of radio stations Wikipedia store 2 Defunct 3 See also Interaction 4 References Help 5 Bibliography About Wikipedia Community portal 6 External links Recent changes 7 Images Contact page Tools List of radio stations [edit] What links here This list is complete and up to date as of March 18, 2019. Related changes Upload file Call Special pages Frequency City of License[1][2] Licensee Format[3] sign open in browser PRO version Are you a developer? Try out the HTML to PDF API pdfcrowd.com sign Permanent link Page information DJRD Broadcasting, KAAM 770 AM Garland Christian Talk/Brokered Wikidata item LLC Cite this page Aleluya Print/export KABA 90.3 FM Louise Broadcasting Spanish Religious Create a book Network Download as PDF Community Printable version New Country/Texas Red KABW 95.1 FM Baird Broadcast Partners Dirt In other projects LLC Wikimedia Commons KACB- Saint Mary's 96.9 FM College Station Catholic LP Catholic Church Languages Add links Alvin Community KACC 89.7 FM Alvin Album-oriented rock College KACD- Midland Christian 94.1 FM Midland Spanish Religious LP Fellowship, Inc. -

Challenging Stereotypes

Challenging Stereotypes How the stereotypical portrayals of Muslims and Islam are challenged through the enemies in Homeland Gunhild-Marie Høie A Thesis Presented to the Departure of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the MA degree University of Oslo Spring 2014 I II Challenging Stereotypes How the stereotypical portrayals of Muslims and Islam are challenged through the enemies in Homeland Gunhild-Marie Høie A Thesis Presented to the Departure of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the MA degree University of Oslo Spring 2014 III © Gunhild-Marie Høie 2014 Challenging Stereotypes: How the stereotypical portrayals of Muslims and Islam are challenged in Homeland. http://www.duo.uio.no Print: Reprosentralen, University of Oslo IV V Abstract Following the terrorist attack on 9/11, actions and practices of the United States government, as well as the dominant media discourse and non-profit media advertising, contributed to create a post-9/11 climate in which Muslims and Arabs were viewed as non-American. This established a binary paradigm between Americans and Muslims, where Americans represented “us” whereas Muslims represented “them.” Through a qualitative analysis of the main characters in the post-9/11 terrorism-show, Homeland, season one (2011), as well as an analysis of the opening sequence and the overall narrative in the show, this thesis argues that this binary system of “us” and “them” is no longer black and white, but blurred, and hard to define. My analysis indicates that several of the enemies in the show break with the stereotypical portrayal of Muslims as crude, violent fanatics. -

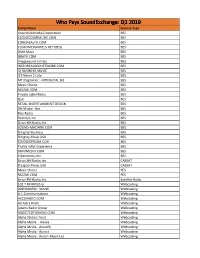

Licensee Count Q1 2019.Xlsx

Who Pays SoundExchange: Q1 2019 Entity Name License Type Aura Multimedia Corporation BES CLOUDCOVERMUSIC.COM BES COROHEALTH.COM BES CUSTOMCHANNELS.NET (BES) BES DMX Music BES GRAYV.COM BES Imagesound Limited BES INSTOREAUDIONETWORK.COM BES IO BUSINESS MUSIC BES It'S Never 2 Late BES MTI Digital Inc - MTIDIGITAL.BIZ BES Music Choice BES MUZAK.COM BES Private Label Radio BES Qsic BES RETAIL ENTERTAINMENT DESIGN BES Rfc Media - Bes BES Rise Radio BES Rockbot, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc BES SOUND-MACHINE.COM BES Stingray Business BES Stingray Music USA BES STUDIOSTREAM.COM BES Thales Inflyt Experience BES UMIXMEDIA.COM BES Vibenomics, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc CABSAT Stingray Music USA CABSAT Music Choice PES MUZAK.COM PES Sirius XM Radio, Inc Satellite Radio 102.7 FM KPGZ-lp Webcasting 999HANKFM - WANK Webcasting A-1 Communications Webcasting ACCURADIO.COM Webcasting Ad Astra Radio Webcasting Adams Radio Group Webcasting ADDICTEDTORADIO.COM Webcasting Aloha Station Trust Webcasting Alpha Media - Alaska Webcasting Alpha Media - Amarillo Webcasting Alpha Media - Aurora Webcasting Alpha Media - Austin-Albert Lea Webcasting Alpha Media - Bakersfield Webcasting Alpha Media - Biloxi - Gulfport, MS Webcasting Alpha Media - Brookings Webcasting Alpha Media - Cameron - Bethany Webcasting Alpha Media - Canton Webcasting Alpha Media - Columbia, SC Webcasting Alpha Media - Columbus Webcasting Alpha Media - Dayton, Oh Webcasting Alpha Media - East Texas Webcasting Alpha Media - Fairfield Webcasting Alpha Media - Far East Bay Webcasting Alpha Media