Tree Management Experts Consulting Arborists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CITES Norfolk Island Boobook Review

Original language: English AC28 Doc. 20.3.6 CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ___________________ Twenty-eighth meeting of the Animals Committee Tel Aviv (Israel), 30 August-3 September 2015 Interpretation and implementation of the Convention Species trade and conservation Periodic review of species included in Appendices I and II (Resolution Conf 14.8 (Rev CoP16)) PERIODIC REVIEW OF NINOX NOVAESEELANDIAE UNDULATA 1. This document has been submitted by Australia.1 2. After the 25th meeting of the Animals Committee (Geneva, July 2011) and in response to Notification No. 2011/038, Australia committed to the evaluation of Ninox novaeseelandiae undulata as part of the Periodic review of the species included in the CITES Appendices. 3. This taxon is endemic to Australia. 4. Following our review of the status of this species, Australia recommends the transfer of Ninox novaeseelandiae undulata from CITES Appendix I to CITES Appendix II, in accordance with provisions of Resolution Conf. 9.24 (Rev CoP16), Annex 4 precautionary measure A.1. and A.2.a) i). 1 The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CITES Secretariat (or the United Nations Environment Programme) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author. AC28 Doc. 20.3.6 – p. 1 AC28 Doc. 20.3.6 Annex CoP17 Prop. xx CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________________ DRAFT PROPOSAL TO AMEND THE APPENDICES (in accordance with Annex 4 to Resolution Conf. -

Cook Pine) Aqueous Resin Extract Against Major Phytopathogens

MAY 2014 – JULY 2014, Vol. 4, No. 3; 2108-2112. E- ISSN: 2249 –1929 Journal of Chemical, Biological and Physical Sciences An International Peer Review E-3 Journal of Sciences Avail able online at www.jcbsc.org Section B: Biological Sciences CODEN (USA): JCBPAT Research Article Bio-Fungicide Potential of Araucaria Columnaris (Cook Pine) Aqueous Resin Extract Against Major Phytopathogens Saranya Devi. K* 1, J. Rathinamala 1 and S. Jayashree 2 1Department of Microbiology, Nehru Arts and Science College, Coimbatore, 2Department of Biotechnology, Nehru Arts and Science College, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India. Received: 05 March 2014 ; Revised: 25 April 2014 ; Accepted: 03 May 2014 Abstract: Use of chemical fungicide to control plant diseases causes several adverse effects such as, development of resistance in the pathogen, residual toxicity, pollution to the environment etc. So an alternative way to overcome the usage of dreadful chemicals is very important. The use of plant extracts as biofungicide is one of the popular and effective method. Araucaria columnaris is a commonly seen ornamental plant known as Christmas tree. It’s a South African species, under the family Araucariaceae. Hence, in the present study, the plant resin extract was tested in-vitro against major plant pathogensby preliminary bioassay. It was found that up to 95% reduction of mycelium growth was observed against major phytopathogens such as Fusarium oxysporyum , Rhizoctonia sp, Cylindrocladium sp, Alternaria sp, and Colletrotricum sp., causing tomato wilt, damping off, foliage blight, and leaf blight diseases in economically important plants. Up to our knowledge it is the first report showing the antifungal activity of Araucaria columnaris resin as antifungal agent. -

Amelanchier Alnifolia. Araucaria Araucana

Woodland Garden Plants The present-day cultivation of large areas of single annual crops such as wheat might seem, on the surface, to be a very productive and efficient use of land (average wheat yields this century have increased more than three-fold to over 3 tons per acre). When other factors are taken into account, however, it can be argued that this is a very unproductive and unsustainable use of the land. A woodland, on the other hand, might seem to be a very unproductive area for human food (unless you happen to like eating acorns). By choosing the right species, however, a woodland garden can produce a larger crop of food than the same area of wheat, will require far less work to manage it and will be able to be sustainably harvested without harm to the soil or the environment in general. I do not intend to go into any more details of the pros and cons of annuals versus perennials here. If you would like more information on this subject then please see our leaflet Why Perennials. One of the main reasons why a woodland garden can be so productive is that such a wide range of plants can be grown together, making much more efficient use of the land. The greater the diversity of plants being grown together then the greater the overall growth of plant matter there is. Thus you can have tall growing trees with smaller trees and shrubs that can tolerate some shade growing under them. Climbing plants can make their own ways up the trees and shrubs towards the light, whilst shade- tolerant herbaceous plants and bulbs can grow on the woodland floor. -

Hundred Acres Reserve Draft Plan of Management

PLAN OF MANAGEMENT HUNDRED ACRES RESERVE 2019 - 2029 Hundred Acres Reserve Plan of Management 2019-2029 Page 2 of 49 Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ 5 1.1 RESERVE DESCRIPTION ................................................................................................................................. 5 1.2 PUBLIC CONSULTATION AND PLANNING FRAMEWORK ........................................................................................ 5 1.3 HERITAGE LISTING ....................................................................................................................................... 7 2 SIGNIFICANCE OF HUNDRED ACRES RESERVE ........................................................................................... 8 2.1 GEOLOGY AND LANDFORM ............................................................................................................................ 9 2.2 FLORA ..................................................................................................................................................... 10 2.2.1 Past clearing and revegetation ........................................................................................................ 10 2.2.2 Current vegetation within the Reserve ............................................................................................ 12 2.2.3 Significant Plant Species ................................................................................................................. -

Ventnor Botanic Garden

Dinosaurs and plants DAWN REDWOOD – Metasequoia glyptostroboides The discovery of this conifer in Szechuan in 1947 created a The Isle of Wight is one of the most important dinosaur horticultural sensation. It was recognised as a descendant of discovery and excavation sites in the world. More than trees from the Carboniferous period, which means it dates back twenty types have now been found, all within a few miles to a time before even the dinosaurs had evolved. of Ventnor Botanic Garden. CYCADS – Cycas revolute In early Cretaceous times when dinosaurs ruled, plant Cycads were the most frequent plants in a life was abundant but very different from now. Just a few dinosaur landscape. Fossils of their 'dinosaur plants' have survived. Ventnor Botanic Garden distinctive cones – like pineapples, to Ventnor Botanic Garden is which they are related – are found on the fortunate to house some of the Island. Though no longer most important ‘living fossils’ widespread, many species of Cycad thrive that covered the Earth during in warmer climates. There is a Cycad with- the time of the dinosaurs. The Isle of Wight in the Early in the garden that is flowering—this is the Cretaceous period 125 million first flowering Cycad in 250 MILLION years ago years! Can you find it? MAGNOLIA – Magnolia spp GINKGO TREES – Ginkgo biloba This ancient and beautiful group of plants evolved towards the The Ginkgo tree has remained the same over 240 million end of the dinosaur age, and is one of the very first flowering years and its distinctive leaf shape is instantly recognisable plants. -

Tortworth Arboretum

4 5 bee 3 garden ARENA With the help of a team of dedicated volunteers we 2 have restored lost pathways, uncovered hidden redwoods 6 features and created new routes around the 7 arboretum. Below is a pick of our favourite trees! STILE 1 Hungarian Oak (Quercus frainetto) 2 Veteran Common Oak (Quercus robur) 8 3 DONKEY BRIDGE Veteran Sweet Chestnuts (Castanea sativa) 1 4 Monkey Puzzle (Araucaria araucana) 9 5 Caucasian Alder (Alnus subcordata) 6 Coastal Redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) PUBLIC FOOTPATH 7 Handkerchief Tree (Davidia involucrata) subsp. 8 (Fraxinus angustifolia 10 Narrow Leaved Ash angustifolia) GATE 11 MAIN 9 Contorted Hazel (Corylus avellana ‘Contorta’) CAMPFIRE 10 Indian Chestnut (Aesculus indica) 11 TOILET Japanese Chestnut (Aesculus turbinata) 12 12 Dawn Redwood (Metasequoia glyptostroboides) 13 Hornbeam (Carpinus betulus) Find us online for details of volunteering opportunities 13 and events, plus more maps and history of the arboretum. https://tortwortharboretum.org ENTRANCE GATE 1 Hungarian Oak (Quercus frainetto) 8 Narrow Leaved Ash (Fraxinus angustifolia subsp. angustifolia) One of our champion trees, over five meters in circumference. Look Grown on common ash root stock, this is a particularly large mature out for the large lobed leaves. (Southeastern Europe and Turkey) specimen for the UK. (Western Europe, northwest Africa) 2 Common Oak (Quercus robur) 9 Contorted Hazel (Corylus avellana ‘Contorta’) This vetern ‘English Oak’ is estimated to be over 350 years old and A natural mutation of common hazel, famously first discovered in a predates the arboretum, being planted as part of a former deer hedgerow at Frocester in 1863. All contorted hazels, including this park. -

Trees of Bayview Cemetery

1 Bigleaf Maple (n) Acer macrophyllum 40 English Midland Hawthorn Crataegus laevigata 2 Japanese Dwarf Maple Acer palmatum 41 Japanese Snowbell Tree Styrax japonica 3 Norway Maple Acer platanoides 42 Yulan Magnolia Magnolia denudata 3a Crimson King Norway Acer platanoides ‘Crimson King’ 43 Dawn Redwood Metasequoia glyptostroboides Trees of Bayview Cemetery Maple ‘ 44 Monkey Puzzle Araucaria araucana 4 Paperbark Maple Acer griseum 45 Flowering Pear Pyrus calleryana ‘Cleveland Select’ This map shows one representative tree from each species found at 5 Red Maple Acer rubrum ‘Cleveland Select’ Bayview. For a complete map, please visit Park Operations, located 6 Vine Maple (n) Acer circinatum 46 White Ash Fraxinus americana across the street from Bayview Cemetary at 1400 Woburn St. 7 Red Snakebark Maple Acer capillipes 47 Smoothleaf Elm Ulmus minor clone or hybrid 8 Sugar Maple Acer saccharum clone or hybrid Trees of 9 Western Redcedar (n) Thuja plicata 47a Jersey or Guernsey Elm Ulmus minor ‘Sarniensis’ 10 Northern White Cedar Thuja occidentalis 48* Wych Elm Ulmus glabra 11 Oriental Arborvitae Thuja orientalis 49 Rhododendron Rhododendron sp. Bayview 12* Port Orford Cedar Chamaecyparis lawsoniana 50 Persian Ironwood Parrotia persica 13 Sawara Cypress Chamaecyparis pisifera 51 Austrian Pine Pinus nigra 13a Plume Sawara Cypress Chamaecyparis pisifera f. plumosa 52 Common Horse Chestnut Aesculus hippocastanum 13b Moss Sawara Cypress Chamaecyparis pisifera f. squarrosa 53 Ginkgo or Maidenhair Tree Ginkgo biloba Cemetery 13c Threadbranch Sawara Chamaecyparis pisifera f. filifera 54 Goldenchain Laburnum anagyroides Cypress 55 Atlas Cedar Cedrus atlantica 14 Mazzard Cherry Prunus avium 56 European Hazel Corylus avellana 15 Canada Red Chokecherry Prunus virginiana 57 Black Locust Robinia pseudoacacia ‘Canada Red’ 58 Sweetgum Liquidambar styraciflua 16 Cherry Plum Prunus ceracifera 59 Eastern Redcedar Juniperus virginiana 16a Purpleleaf Plum Prunus ceracifera 60 English Holly Ilex aquifolium f. -

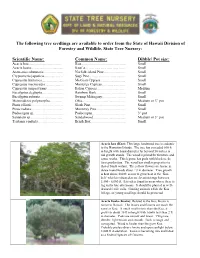

The Following Tree Seedlings Are Available to Order from the State of Hawaii Division of Forestry and Wildlife, State Tree Nursery

The following tree seedlings are available to order from the State of Hawaii Division of Forestry and Wildlife, State Tree Nursery: Scientific Name: Common Name: Dibble/ Pot size: Acacia koa……………………… Koa……………………………….. Small Acacia koaia……………………... Koai’a……………………………. Small Araucaria columnaris…………….. Norfolk-island Pine……………… Small Cryptomeria japonica……………. Sugi Pine………………………… Small Cupressus lusitanica……………... Mexican Cypress………………… Small Cupressus macrocarpa…………… Monterey Cypress……………….. Small Cupressus simpervirens………….. Italian Cypress…………………… Medium Eucalyptus deglupta……………… Rainbow Bark……………………. Small Eucalyptus robusta……………….. Swamp Mahogany……………….. Small Metrosideros polymorpha……….. Ohia……………………………… Medium or 3” pot Pinus elliotii……………………… Slash Pine………………………... Small Pinus radiata……………………... Monterey Pine…………………… Small Podocarpus sp……………………. Podocarpus………………………. 3” pot Santalum sp……………………… Sandalwood……………………… Medium or 3” pot Tristania conferta………………… Brush Box………………………... Small Acacia koa (Koa): This large hardwood tree is endemic to the Hawaiian Islands. The tree has exceeded 100 ft in height with basal diameter far beyond 50 inches in old growth stands. The wood is prized for furniture and canoe works. This legume has pods with black seeds for reproduction. The wood has similar properties to that of black walnut. The yellow flowers are borne in dense round heads about 2@ in diameter. Tree growth is best above 800 ft; seems to grow best in the ‘Koa belt’ which is situated at an elevation range between 3,500 - 6,000 ft. It is often found in areas where there is fog in the late afternoons. It should be planted in well- drained fertile soils. Grazing animals relish the Koa foliage, so young seedlings should be protected Acacia koaia (Koaia): Related to the Koa, Koaia is native to Hawaii. The leaves and flowers are much the same as Koa. -

Fossil MRI D

Biogeosciences Discuss., 4, 2959–3004, 2007 Biogeosciences www.biogeosciences-discuss.net/4/2959/2007/ Discussions BGD © Author(s) 2007. This work is licensed 4, 2959–3004, 2007 under a Creative Commons License. Biogeosciences Discussions is the access reviewed discussion forum of Biogeosciences Fossil MRI D. Mietchen et al. Title Page Three-dimensional Magnetic Resonance Abstract Introduction Imaging of fossils across taxa Conclusions References Tables Figures D. Mietchen1,2,3, M. Aberhan4, B. Manz1, O. Hampe4, B. Mohr4, C. Neumann4, and 1 F. Volke J I 1 Fraunhofer Institute for Biomedical Engineering (IBMT), 66386 St. Ingbert, Germany J I 2University of the Saarland, Faculty of Physics and Mechatronics, 66123 Saarbrucken,¨ Germany Back Close 3Friedrich-Schiller University Jena, Department of Psychiatry, 07740 Jena, Germany Full Screen / Esc 4Humboldt-Universitat¨ zu Berlin, Museum fur¨ Naturkunde, 10099 Berlin, Germany Received: 22 August 2007 – Accepted: 27 August 2007 – Published: 27 August 2007 Printer-friendly Version Correspondence to: D. Mietchen ([email protected]) Interactive Discussion EGU 2959 Abstract BGD The visibility of life forms in the fossil record is largely determined by the extent to which they were mineralised at the time of their death. In addition to mineral structures, many 4, 2959–3004, 2007 fossils nonetheless contain detectable amounts of residual water or organic molecules, 5 the analysis of which has become an integral part of current palaeontological research. Fossil MRI The methods available for this sort of investigations, though, typically require dissolu- tion or ionisation of the fossil sample or parts thereof, which is an issue with rare taxa D. Mietchen et al. -

Gymnosperms on the EDGE Félix Forest1, Justin Moat 1,2, Elisabeth Baloch1, Neil A

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Gymnosperms on the EDGE Félix Forest1, Justin Moat 1,2, Elisabeth Baloch1, Neil A. Brummitt3, Steve P. Bachman 1,2, Stef Ickert-Bond 4, Peter M. Hollingsworth5, Aaron Liston6, Damon P. Little7, Sarah Mathews8,9, Hardeep Rai10, Catarina Rydin11, Dennis W. Stevenson7, Philip Thomas5 & Sven Buerki3,12 Driven by limited resources and a sense of urgency, the prioritization of species for conservation has Received: 12 May 2017 been a persistent concern in conservation science. Gymnosperms (comprising ginkgo, conifers, cycads, and gnetophytes) are one of the most threatened groups of living organisms, with 40% of the species Accepted: 28 March 2018 at high risk of extinction, about twice as many as the most recent estimates for all plants (i.e. 21.4%). Published: xx xx xxxx This high proportion of species facing extinction highlights the urgent action required to secure their future through an objective prioritization approach. The Evolutionary Distinct and Globally Endangered (EDGE) method rapidly ranks species based on their evolutionary distinctiveness and the extinction risks they face. EDGE is applied to gymnosperms using a phylogenetic tree comprising DNA sequence data for 85% of gymnosperm species (923 out of 1090 species), to which the 167 missing species were added, and IUCN Red List assessments available for 92% of species. The efect of diferent extinction probability transformations and the handling of IUCN data defcient species on the resulting rankings is investigated. Although top entries in our ranking comprise species that were expected to score well (e.g. Wollemia nobilis, Ginkgo biloba), many were unexpected (e.g. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE ORCID ID: 0000-0003-0186-6546 Gar W. Rothwell Edwin and Ruth Kennedy Distinguished Professor Emeritus Department of Environmental and Plant Biology Porter Hall 401E T: 740 593 1129 Ohio University F: 740 593 1130 Athens, OH 45701 E: [email protected] also Courtesy Professor Department of Botany and PlantPathology Oregon State University T: 541 737- 5252 Corvallis, OR 97331 E: [email protected] Education Ph.D.,1973 University of Alberta (Botany) M.S., 1969 University of Illinois, Chicago (Biology) B.A., 1966 Central Washington University (Biology) Academic Awards and Honors 2018 International Organisation of Palaeobotany lifetime Honorary Membership 2014 Fellow of the Paleontological Society 2009 Distinguished Fellow of the Botanical Society of America 2004 Ohio University Distinguished Professor 2002 Michael A. Cichan Award, Botanical Society of America 1999-2004 Ohio University Presidential Research Scholar in Biomedical and Life Sciences 1993 Edgar T. Wherry Award, Botanical Society of America 1991-1992 Outstanding Graduate Faculty Award, Ohio University 1982-1983 Chairman, Paleobotanical Section, Botanical Society of America 1972-1973 University of Alberta Dissertation Fellow 1971 Paleobotanical (Isabel Cookson) Award, Botanical Society of America Positions Held 2011-present Courtesy Professor of Botany and Plant Pathology, Oregon State University 2008-2009 Visiting Senior Researcher, University of Alberta 2004-present Edwin and Ruth Kennedy Distinguished Professor of Environmental and Plant Biology, Ohio -

The Bulletin, 2019 Fall/Winter Issue

Vol XXXV No. 3 FALL-WINTER 2019 the bulletinof the National Tropical Botanical Garden contents From all of us at NTBG, 3 MESSAGE FROM THE CEO/DIRECTOR ON THE COVER The green, red, and white in this American here's wishing you and your family the very best holly (Ilex opaca) illustration captures features the spirit of the season. This issue of The Bulletin features works by members of holiday season and a happy new year. 4 KEEP COOL, STAY DRY, AND YOU MAY NTBG’s Florilegium Society including LIVE LONG botanical artist and instructor Wendy Hollender (cover image). by Dustin Wolkis and Marian Chau The Bulletin is a publication for supporters of the National Tropical Botanical Garden, 8 SPLITTING HAIRS (EVEN WHEN THERE a not-for-profit institution dedicated to ARE NONE) tropical plant conservation, scientific by Dr. David H. Lorence research, and education. We encourage you to share this 18 INTERVIEW: DR. NINA RØNSTED, publication with your family and friends. NTBG’S NEW DIRECTOR OF SCIENCE If your household is receiving more than one copy and you wish to receive only AND CONSERVATION one, please inform our Development Office at our national headquarters at: [email protected]. in every issue National Tropical Botanical Garden 3530 Papalina Road, Kalāheo RED LISTED Hawai‘i 96741 USA 12 Tel. (808) 332-7324 Fax (808) 332-9765 THE GREEN THUMB [email protected] 13 www. ntbg.org 16 GARDEN SPROUTS ©2019 National Tropical Botanical Garden News from around the Garden ISSN 1057-3968 All rights reserved. Photographs are the property of NTBG unless otherwise noted.