13. IS PANJAL a Nampütint VILLAGE?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

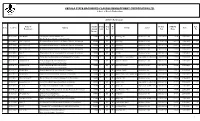

2015-16 Term Loan

KERALA STATE BACKWARD CLASSES DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION LTD. A Govt. of Kerala Undertaking KSBCDC 2015-16 Term Loan Name of Family Comm Gen R/ Project NMDFC Inst . Sl No. LoanNo Address Activity Sector Date Beneficiary Annual unity der U Cost Share No Income 010113918 Anil Kumar Chathiyodu Thadatharikathu Jose 24000 C M R Tailoring Unit Business Sector $84,210.53 71579 22/05/2015 2 Bhavan,Kattacode,Kattacode,Trivandrum 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $52,631.58 44737 18/06/2015 6 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $157,894.74 134211 22/08/2015 7 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $109,473.68 93053 22/08/2015 8 010114661 Biju P Thottumkara Veedu,Valamoozhi,Panayamuttom,Trivandrum 36000 C M R Welding Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 13/05/2015 2 010114682 Reji L Nithin Bhavan,Karimkunnam,Paruthupally,Trivandrum 24000 C F R Bee Culture (Api Culture) Agriculture & Allied Sector $52,631.58 44737 07/05/2015 2 010114735 Bijukumar D Sankaramugath Mekkumkara Puthen 36000 C M R Wooden Furniture Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 22/05/2015 2 Veedu,Valiyara,Vellanad,Trivandrum 010114735 Bijukumar D Sankaramugath Mekkumkara Puthen 36000 C M R Wooden Furniture Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 25/08/2015 3 Veedu,Valiyara,Vellanad,Trivandrum 010114747 Pushpa Bhai Ranjith Bhavan,Irinchal,Aryanad,Trivandrum -

List of Teachers Posted from the Following Schools to Various Examination Centers As Assistant Superintendents for Higher Secondary Exam March 2015

LIST OF TEACHERS POSTED FROM THE FOLLOWING SCHOOLS TO VARIOUS EXAMINATION CENTERS AS ASSISTANT SUPERINTENDENTS FOR HIGHER SECONDARY EXAM MARCH 2015 08001 - GOVT SMT HSS,CHELAKKARA,THRISSUR 1 DILEEP KUMAR P V 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR 04884231495, 9495222963 2 SWAPNA P 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR , 9846374117 3 SHAHINA.K 08035-GOVT. RSR VHSS, VELUR, THRISSUR 04885241085, 9447751409 4 SEENA M 08041-GOVT HSS,PAZHAYANNOOR,THRISSUR 04884254389, 9447674312 5 SEENA P.R 08046-AKM HSS,POOCHATTY,THRISSUR 04872356188, 9947088692 6 BINDHU C 08062-ST ANTONY S HSS,PUDUKAD,THRISSUR 04842331819, 9961991555 7 SINDHU K 08137-GOVT. MODEL HSS FOR GIRLS, THRISSUR TOWN, , 9037873800 THRISSUR 8 SREEDEVI.S 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR , 9020409594 9 RADHIKA.R 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR 04742552608, 9847122431 10 VINOD P 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR , 9446146634 11 LATHIKADEVI L A 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR 04742482838, 9048923857 12 REJEESH KUMAR.V 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR 04762831245, 9447986101 08002 - GOVT HSS,CHERPU,THRISSUR 1 PREETHY M K 08003-GOVT MODEL GHSS, IRINJALAKKUDA, THRISSUR 04802820505, 9496288495 2 RADHIKA C S 08003-GOVT MODEL GHSS, IRINJALAKKUDA, THRISSUR , 9495853650 3 THRESSIA A.O 08005-GOVT HSS,KODAKARA,THRISSUR 04802726280, 9048784499 4 SMITHA M.K 08046-AKM HSS,POOCHATTY,THRISSUR 04872317979, 8547619054 5 RADHA M.R 08050-ST ANTONY S HSS,AMMADAM,THRISSUR 04872342425, 9497180518 6 JANITHA K 08050-ST ANTONY S HSS,AMMADAM,THRISSUR 04872448686, 9744670871 1 7 SREELEKHA.E.S 08050-ST ANTONY S HSS,AMMADAM,THRISSUR 04872343515, 9446541276 8 APINDAS T T 08095-ST. PAULS CONVENT EHSS KURIACHIRA, THRISSUR, 04872342644, 9446627146 680006 9 M.JAMILA BEEVI 08107-SN GHSS, KANIMANGALAM, THRISSUR, 680027 , 9388553667 10 MANJULA V R 08118-TECHNICAL HSS, VARADIAM, THRISSUR, 680547 04872216227, 9446417919 11 BETSY C V 08138-GOVT. -

![Ticf Kkddv KERALA GAZETTE B[Nimcniambn {]Kn≤S∏Spøp∂Xv PUBLISHED by AUTHORITY](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9289/ticf-kkddv-kerala-gazette-b-nimcniambn-kn-s-sp%C3%B8p-xv-published-by-authority-329289.webp)

Ticf Kkddv KERALA GAZETTE B[Nimcniambn {]Kn≤S∏Spøp∂Xv PUBLISHED by AUTHORITY

© Regn. No. KERBIL/2012/45073 tIcf k¿°m¿ dated 5-9-2012 with RNI Government of Kerala Reg. No. KL/TV(N)/634/2015-17 2016 tIcf Kkddv KERALA GAZETTE B[nImcnIambn {]kn≤s∏SpØp∂Xv PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY 2016 Pq¨ 14 Xncph\¥]pcw, hmeyw 5 14th June 2016 \º¿ sNmΔ 1191 CShw 31 31st Idavam 1191 24 Vol. V } Thiruvananthapuram, No. } 1938 tPyjvTw 24 Tuesday 24th Jyaishta 1938 PART IB Notifications and Orders issued by the Kerala Public Service Commission NOTIFICATIONS (2) (1) No. Estt.III(1)35557/03/GW. Thiruvananthapuram, 10th May 2016. No. Estt.III(1)35150/03/GW. Thiruvananthapuram, 10th May 2016. The following is the list of Deputy Secretaries found The following is the list of Joint Secretaries found fit fit by the Departmental Promotion Committee and by the Departmental Promotion Committee and approved approved by the Kerala Public Service Commission for by the Kerala Public Service Commission for promotion to promotion to the post of Joint Secretary/Regional Officer the post of Additional Secretary in the Office of the in the Office of the Kerala Public Service Commission for Kerala Public Service Commission for the year 2016. the year 2016. 1. Sri Ramesh Sarma, P. 1. Smt. Sheela Das 2. Sri Thomas M. Mathew 2. Sri Ganesan, K. 3. Smt. Vijayamma, P. R. 3. Sri Sandeep, N. The above list involves no supersession. The above list involves no supersession. 21 14th JUNE 2016] KERALA GAZETTE 586 (3) NOTIFICATION No. Estt.III(1)35933/03/GW. No. Estt.III(1)36207/03/GW. Thiruvananthapuram, 10th May 2016. -

State District Branch Address Centre Ifsc Contact1 Contact2 Contact3 Micr Code Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Rajamundry Pb No

STATE DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS CENTRE IFSC CONTACT1 CONTACT2 CONTACT3 MICR_CODE M RAGHAVA RAO E- MAIL : PAUL RAJAMUN KAKKASSERY PB NO 23, FIRST DRY@CSB E-MAIL : FLOOR, STADIUM .CO.IN, RAJAMUNDRY ROAD, TELEPHO @CSB.CO.IN, ANDHRA EAST RAJAMUNDRY, EAST RAJAHMUN NE : 0883 TELEPHONE : PRADESH GODAVARI RAJAMUNDRY GODAVARY - 533101 DRY CSBK0000221 2421284 0883 2433516 JOB MATHEW, SENIOR MANAGER, VENKATAMATTUPAL 0863- LI MANSION,DOOR 225819, NO:6-19-79,5&6TH 222960(DI LANE,MAIN R) , CHANDRAMOH 0863- ANDHRA RD,ARUNDELPET,52 GUNTUR@ ANAN , ASST. 2225819, PRADESH GUNTUR GUNTUR 2002 GUNTUR CSBK0000207 CSB.CO.IN MANAGER 2222960 D/NO 5-9-241-244, Branch FIRST FLOOR, OPP. Manager GRAMMER SCHOOL, 040- ABID ROAD, 23203112 e- HYDERABAD - mail: ANDHRA 500001, ANDHRA HYDERABA hyderabad PRADESH HYDERABAD HYDERABAD PRADESH D CSBK0000201 @csb.co.in EMAIL- SECUNDE 1ST RABAD@C FLOOR,DIAMOND SECUNDER SB.CO.IN TOWERS, S D ROAD, ABAD PHONE NO ANDHRA SECUNDERABA DECUNDERABAD- CANTONME 27817576,2 PRADESH HYDERABAD D 500003 NT CSBK0000276 7849783 THOMAS THARAYIL, USHA ESTATES, E-MAIL : DOOR NO 27.13.28, VIJAYAWA NAGABHUSAN GOPALAREDDY DA@CSB. E-MAIL : ROAD, CO.IN, VIJAYAWADA@ GOVERNPOST, TELEPHO CSB.CO.IN, ANDHRA VIJAYAWADA - VIJAYAWAD NE : 0866 TELEPHONE : PRADESH KRISHNA VIJAYAWADA 520002 A CSBK0000206 2577578 0866 2571375 MANAGER, E-MAIL: NELLORE ASST.MANAGE @CSB.CO. R, E-MAIL: PB NO 3, IN, NELLORE@CS SUBEDARPET ROAD, TELEPHO B.CO.IN, ANDHRA NELLORE - 524001, NE:0861 TELEPHONE: PRADESH NELLORE NELLORE ANDHRA PRADESH NELLORE CSBK0000210 2324636 0861 2324636 BR.MANAG ER : PHONE :040- ASST.MANAGE 23162666 R : PHONE :040- 5-222 VIVEKANANDA EMAIL 23162666 NAGAR COLONY :KUKATPA EMAIL ANDHRA KUKATPALLY KUKATPALL LLY@CSB. -

Chelakkara Assembly Kerala Factbook

Editor & Director Dr. R.K. Thukral Research Editor Dr. Shafeeq Rahman Compiled, Researched and Published by Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. D-100, 1st Floor, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-I, New Delhi- 110020. Ph.: 91-11- 43580781, 26810964-65-66 Email : [email protected] Website : www.electionsinindia.com Online Book Store : www.datanetindia-ebooks.com Report No. : AFB/KR-061-0619 ISBN : 978-93-5313-530-0 First Edition : January, 2018 Third Updated Edition : June, 2019 Price : Rs. 11500/- US$ 310 © Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical photocopying, photographing, scanning, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. Please refer to Disclaimer at page no. 128 for the use of this publication. Printed in India No. Particulars Page No. Introduction 1 Assembly Constituency -(Vidhan Sabha) at a Glance | Features of Assembly 1-2 as per Delimitation Commission of India (2008) Location and Political Maps Location Map | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency -(Vidhan Sabha) in 2 District | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency under Parliamentary 3-9 Constituency -(Lok Sabha) | Town & Village-wise Winner Parties- 2019, 2016, 2014, 2011 and 2009 Administrative Setup 3 District | Sub-district | Towns | Villages | Inhabited Villages | Uninhabited 10-11 Villages | Village Panchayat | Intermediate Panchayat Demographics 4 Population | Households | Rural/Urban Population | Towns and Villages -

Accused Persons Arrested in Thrissur City District from 09.12.2018To15.12.2018

Accused Persons arrested in Thrissur City district from 09.12.2018to15.12.2018 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 KARIMBANAKKA MANNUTH RETHEESH L HOUSE, 15-12-2018 770/2018 U/s MATHEW K 59, MANNUTHY Y P.M. SI OF BAILED BY 1 THOMAS NELLIMATTOM, at 22:20 118(a) of KP T Male BYE PASS (THRISSUR POLICE, POLICE KOTHAMANGALA Hrs Act CITY) MANNUTHY M, ERANAKULAM CHAVAKA CHALIL HOUSE, 15-12-2018 693/2018 U/s ABDUL 39, CHAVAKKA D JAYAPRADE BAILED BY 2 RASHEED KETTUNGAL at 21:00 279 IPC & 185 RAHIMAN Male D (THRISSUR EP .K.G POLICE ANCHANGADI Hrs MV ACT CITY) GURUVAY THAIKKATTIL (H), 15-12-2018 758/2018 U/s SI SURENDRA 27, THAMPURA UR BAILED BY 3 NIKHIL PERAKAM, at 20:15 279 IPC & 185 PREMARAJA N Male NPADI (THRISSUR POLICE POOKODE Hrs MV ACT N CITY) KARIVAN HOUSE, MEDICAL KANNAMKULAM 15-12-2018 798/2018 U/s VELAYUDH 58, COLLEGE ANUDAS K 4 GIRIJAN ROAD GRAMALA at 20:20 279 IPC & 185 ARRESTED AN Male (THRISSUR SI OF POLICE MULAMKUNNAT Hrs MV ACT CITY) HUKAVU AVAVNAPARAMB MEDICAL 15-12-2018 797/2018 U/s 24, IL HOUSE, THIRUTHIPA COLLEGE ANUDAS K 5 VIPIN AYYAPPAN at 19:10 15(c) r/w 63 ARRESTED Male PARLIKKAD RAMBU (THRISSUR SI OF POLICE Hrs of Abkari Act DESOM CITY) MEDICAL KOZHIPARAMBIL 15-12-2018 797/2018 U/s 31, THIRUTHIPA COLLEGE ANUDAS K 6 BIJEESH RAMU HOUSE, at 19:10 15(c) r/w 63 ARRESTED Male RAMBU (THRISSUR SI OF POLICE PARLIKKAD Hrs of Abkari Act CITY) THAZHATHETHIL HOUSE THEKKE CHERUTH 15-12-2018 405/2018 U/s GOVINDHA 34, VAVANNUR CHERUTHU URUTHI 7 AJIL at 19:35 279 IPC & 185 V P SIBEESH ARRESTED N Male DESAM RTHY (THRISSUR Hrs MV ACT NAGALASSERY,PA CITY) LAKKAD KAVILVALAPPIL WADAKKA K.C. -

Physicochemical Characteristics of Soils of Talapilli Taluk, Thrissur

Saudi Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences ISSN 2415-6256 (Print) Scholars Middle East Publishers ISSN 2415-6248 (Online) Dubai, United Arab Emirates Website: http://scholarsmepub.com/ Physicochemical Characteristics of Soils of Talapilli Taluk, Thrissur, Kerala, India Shyju K1, Kumaraswamy K2 1UGC BSR Research Scholar & 2UGC BSR Faculty Fellow Department of Geography, Bharathidasan University, Tiruchirappalli, Tamil Nadu, India Abstract: The importance of soil resources to attain sustainability in crop *Corresponding author production, eco-development and protection of environment is an established fact. Shyju K Management of soil on a scientific basis is essential for sustained and increased agricultural production, on this prime perspective a study on physiochemical Article History characters of soils has been conducted in the Talapilli Taluk of Thrissur District, Received: 22.11.2017 India. Talapilli is the agricultural dominant area in the District and hence the study Accepted: 27.11.2017 help in more understanding of the quality of the soil for proper management Published: 30.11.2017 practices in agriculture and other sectors as well. The physiochemical characters analyzed in the study are texture, soil depth, slope, erosion, pH, electrical DOI: conductivity, primary nutrients like available nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium 10.21276/sjhss.2017.2.11.15 and secondary nutrients like magnesium and sulphur. The result indicates that Talapilli has gravelly clay loam and gravelly sandy clay loam soils in higher proportion having moderate to deep soil depth with moderate slope and less to moderate intensity of erosion. As far as chemical composition is concerned in Talapilli Taluk major proportion of soil has pH ranges from 5.1 to 6, that which shows the acidic nature of the soil. -

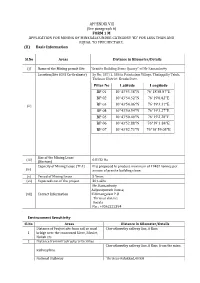

Pillar No Latitude Longitude BP 01 10°43

APPENDIX VIII (See paragraph 6) FORM 1 M APPLICATION FOR MINING OF MINERALS UNDER CATEGORY ‘B2’ FOR LESS THAN AND EQUAL TO FIVE HECTARE. (II) Basic Information Sl.No Areas Distance in Kilometer/Details (i) Name of the Mining permit Site "Granite Building Stone Quarry" of Mr Ramankutty Location/Site (GPS Co-Ordinate) Sy No: 587/1, 586 in Painkulam Village, Thalappilly Taluk, Thrissur District, Kerala State. Pillar No Latitude Longitude BP 01 10°43'53.38"N 76°18'58.87"E BP 02 10°43'54.52"N 76°19'0.82"E (ii) BP 03 10°43'54.06"N 76°19'3.31"E BP 04 10°43'50.54"N 76°19'3.27"E BP 05 10°43'50.40"N 76°19'2.28"E BP 06 10°43'52.88"N 76°19’1.84"E BP 07 10°43'52.73"N 76°18’59.05"E Size of the Mining Lease (iii) 0.8132 Ha (Hectare) Capacity of Mining Lease (TPA) It is proposed to produce maximum of 19481 tonnes per (iv) annum of granite building stone. (v) Period of Mining Lease 5 Years (vi) Expected cost of the project 30 Lakhs Mr. Ramankutty Adiyampurath House, (vii) Contact Information Killimangalam P.O Thrissur district Kerala No. : +9562222394 Environment Sensitivity Sl.No Areas Distance in Kilometer/Details Distance of Project site from rail or road Cheruthuruthy railway line, 6 Kms 1 bridge over the concerned River, Rivulet, Nallah etc. 2 Distance from infrastructural facilities Cheruthuruthy railway line, 6 Kms from the mine. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Thrissur Rural District from 12.11.2017 to 18.11.2017

Accused Persons arrested in Thrissur Rural district from 12.11.2017 to 18.11.2017 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 THOPPIYIL HOUSE CR.952/17 PADIYAM DESAM 12.11.201 U/S 118 (i) KP KRISHNANU 33/17 SANEESH.S.R JFCM NO II 1 ASOKAN PADIYAM VILLAGE MUTTICHUR 7 AT 14.30 ACT & 6 (b ) ANTHIKAD NNI MALE SI OF POLICE THRISSUR ANTHIKAD HRS r/w 24 OF THRISSUR COTPA ACT PARAPPURARTH HOUSE, PARAKAD, 12.11.201 CR.696/17 JFCM 21/17 CHELAKKAR SIBEESH 2 SHINTO BABY VENGANELLUR, CHELAKKARA 7 AT 14.00 U/S 119 (a ) WADAKKAN MALE A SI OF POLICE CHELAKARA HRS KP ACT CHERY THRISSUR CR.658/17 MELEPURAKKAL 12.11.201 P.K JFCM SUBRAMANI 48/17 CHERUTHURU U/S 15 (C ) CHERUTHUR 3 KUTTAN HOUSE AKAMALA 7 AT 12.50 PADMARAJAN WADAKKAN AN MALE THY R/W 63 OF UTHY ENKAKAD THRISSUR HRS SI OF POLICE CHERY ABAKRI ACT POTTAKARAN HOUSE, 12.11.201 CR.1513/17 JFCM 34/17 KARUMATHR IRINJALAKU V.V THOMAS 4 SATHEESAN NARAYANAN NEDUNGANAM, 7 AT 15.00 U/S 15 OF KG IRINJALAKUD MALE A DA SI OF POLICE KARUMATHRA HRS ACT A VILLAGE KARIPPAKULAM HOUSE, 12.11.201 CR.1513/17 JFCM 49/17 KARUMATHRA KARUMATHR IRINJALAKU V.V THOMAS 5 NAZEER HANEEFA 7 AT 15.00 U/S 15 OF KG IRINJALAKUD MALE DESAM, A DA SI OF POLICE HRS ACT A KARUMATHRA VILLAGE PALLIPADAM 12.11.201 CR.1513/17 JFCM 45/17 HOUSE, KADALAYI, KARUMATHR IRINJALAKU V.V THOMAS 6 BASHEER ABDU 7 AT -

Agenda & Notes for the Meeting of the R T a , Thrissur to Be Held on 02-02

1 Agenda & Notes for the Meeting of the R T A , Thrissur to be held on 02-02-2018 at 10.30 A.M (Venue : Conference Hall, District Collectorate, Thrissur) PRESENT : CHAIRMAN :SHRI.DR.A.KOWSIGAN I A S DISTRICT COLLECTOR & CHAIRMAN, R T A, THRISSUR. MEMBER : SHRI YATHISH CHANDRA I. P. S, DISTRICT POLICE CHIEF, THRISSUR RURAL, ( MEMBER, R T A, THRISSUR) MEMBER : SHRI. SHAJI JOSEPH DEPUTY TRANSPORT COMMISSIONER, CENTRAL ZONE-1, THRISSUR. ( MEMBER, R T A, THRISSUR) 2 Item No.1 G-128759/2017 Agenda :. To Consider the application for the grant of fresh regular permit in respect of suitable stage carriage ( 28 seats in all ) to operate on the route Karappadam-Chalakkudy-Thiruthyparambu-Chembankunnu,via Kundukuzhipadam- Koorkamattom-MarancodeStMary’sChurch, Kuttikkadu-Poovathinkal-Paroyaram- Anamala junction-Sadayam College-Vellanchira-Annur-Kottat-Kuttikkadu church- Mechira-Chowka-VGM-Thazhur church-Nayarangadi- as Ordinary service Applicant:Sri. Shaju,Pariyadan House,P O Pattikkad,Thrissur Proposal Timings Karappad Chalakk Thiruthipara Chalakk Karappad Chebanku am udy mbu udy am nnu 6.20 6.58 7.00 7.20 7.40 7.53 8.31 8.32 10.45 10.00/10. 9.40 9.20 07 10.47 11.25 11.30 11.50 12.10 12.48 1.26 2.35 1.57 3.18 4.03 4.53 4.10 5.03 5.46 6.48 6.05 7.46Halt 7.08 Total route length- 54.8KM. Overlapping on the notified route – Nil 3 1) Trip.at,6.20ViaKundukuzhi,Koorkamattom,Kuttikkad,Pariyaram,Anamal a road 2) Trip at,7.00 Via Sadayan College,Vellanchira 3) Trip.at,7.53ViaAnamalaRoad,Pariyaram,Poovathinkal,Kuttikkad, Karunalayam, Kuttichira 4) Trip.at,9.10ViaKundukuzhi,Koorkamattom,Kuttikkad,Pariyaram,Anamal -

BASIC DETAILS 07557--AL IRSHAD ENG SCHOOL KILLIMANGALAM TRICHUR KL Dated : 25/07/2018

7/25/2018 CBSE | FORM BASIC DETAILS 07557--AL IRSHAD ENG SCHOOL KILLIMANGALAM TRICHUR KL Dated : 25/07/2018 SCHOOL NAME AL IRSHAD ENG SCHOOL KILLIMANGALAM TRICHUR KL SCHOOL CODE ADDRESS AL IRSHAD ENGLISH SCHOOL,KILLIMANGALAM AFFILIATION P.O,TRICHUR DIST CODE PRINCIPAL MRS NEJUMA PA PRINCIPAL'S CONTACT NUMBER PRINCIPAL'S EMAIL ID [email protected] PRINCIPAL'S RETIREMENT DATE SCHOOL'S CONTACT 0488-251932 SCHOOL'S EMAIL aies NUMBER ID SCHOOL'S WEBSITE www.alirshadkillimangalam.com SCHOOL'S FAX NUMBER LANDMARK NEAR SCHOOL KERALA KALAMANDALAM, CHERUTHURUTHY YEAR OF ESTABLISHMENT AFFILIATION VALIDITY 2003 TO 2022 AFFILIATION STATUS NAME OF THE DARUL ISHADIL ISLAMIYYA, KILLIMANGALAM REGISTRATION TRUST/SOCIETY/COMPANY DATE REGISTERED WITH SOCIETY REGISTRATION 580/97 REGISTRATION NUMBER VALIDITY NOC ISSUING AUTHORITY STATE GOVERNMENT OF KERALA NOC ISSUING DATE NO OBJECTION VIEW (PdfHandler.aspx? NON PROPRIETY CERTIFICATE FileName=G:\cbse\2018\oasisdemo\noc\07557.PDF) CHARACTER FileName=G:\c AFFIDAVIT/NON PROFIT COMPANY AFFIDAVIT http://59.179.16.89/2018/oasisdemo/finalpage.aspx 1/14 7/25/2018 CBSE | FORM FACULTY DETAILS 07557--AL IRSHAD ENG SCHOOL KILLIMANGALAM TRICHUR KL Dated : 25/07/2018 TOTAL NUMBER OF TEACHERS (ALL CLASSES) 71 NUMBER OF PGTs 10 NUMBER OF TGTs 15 NUMBER OF PRTs 42 NUMBER OF PETs 2 OTHER NON-TEACHING STAFF 15 NUMBER OF MANDATORY TRAINING QUALIFIED 3 NUMBER OF TRAININGS ATTENDED BY FACULTY 25 TEACHERS SINCE LAST YEAR http://59.179.16.89/2018/oasisdemo/finalpage.aspx 2/14 7/25/2018 CBSE | FORM STUDENT DETAILS 07557--AL -

Accused Persons Arrested in Thrissur City District from 01.12.2019To07.12.2019

Accused Persons arrested in Thrissur City district from 01.12.2019to07.12.2019 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 1369/2019 Thrissur KATTUGAL(H), Nr model 07-12-2019 U/s 118(i) of 30, East Bibin si of BAILED BY 1 Jio George ANCHERY , girls school at 22:35 KP Act & 6 Male (Thrissur police POLICE NADATHARA (V) thrissur Hrs r/w 24 of City) COTPA Act CHALLISSERY 07-12-2019 360/2019 U/s GVR Temple 70, KUTTIKKARAN Mammiyoor, BAILED BY 2 JOHNY JOSEPH at 21:05 279 IPC & 185 (Thrissur SI Vargheese Male HOUSE,PAVARAT Guruvayur. POLICE Hrs MV ACT City) TY POTTAMTHADAT 07-12-2019 819/2019 U/s Peramangal ARUN BHAGYAN 18, HIL HOUSE THECHIKKO K C BYJU SI BAILED BY 3 at 19:15 27(b) of am (Thrissur NATH ATHAN Male PERAMANGALAM TTUKAVU OF POLICE POLICE Hrs NDPS Act City) VILLAGE VALIYAKATHU 07-12-2019 Guruvayur SI 23, HOUSE BRAHMAKU 519/2019 U/s BAILED BY 4 SADAK SULAIMAN at 19:53 (Thrissur FAKRUDHEE Male CHOWALLORE LAM 107 CrPC POLICE Hrs City) N KANDANASSERRY PAZHAYA Kottattukulambil 07-12-2019 498/2019 U/s Krishnakum 35, PAZHAYAN NNUR BENNY A A, BAILED BY 5 Rajan House, Thekkethara, at 17:50 279 IPC & 185 ar Male NUR (Thrissur SI OF POLICE POLICE Pazhayannur Hrs MV ACT City) 673/2019 U/s 376(A)(B) IPC & Sec.