Peritextual Images in Young Adult Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Create a Word Document That Uses Different Page Numbering Formats

How to create a Word document that uses different page numbering formats You can use Microsoft Word to create complex documents. Books and other large documents occasionally require different page number formats in different sections of one document. For example, you can number the index pages with Roman numerals (for example, "i.", "ii.", "iii.") and the main document with Arabic numerals (for example, "1", "2", "3"). This article describes how to set up different page numbering formats. Format Page Numbering To format the page numbering for different sections, follow these steps: 1. Click between two parts of your document that you want to number differently. 2. On the Insert menu, click Break. 3. Click Next Page, Even Page, or Odd Page, and then click OK. For Help on an option, click the question mark, and then click the option. 4. Click in the first section. 5. On the View menu, click Header and Footer. 6. Click in the header or footer where you want the page number. 7. On the Header and Footer toolbar, click Insert Page Number. 8. On the Header and Footer toolbar, click Format Page Number. 9. In the Number format box, click the format that you want for the numbers in this section. 10. Do one of the following: o If you want the page numbering for the first page in this section to start at a particular number other than the first number in the format series, click Start at under Page numbering, and then enter the first number that you want to appear on the first page of the section. -

Chapter 5 Formatting Pages: Basics Page Styles and Related Features Copyright

Writer 6.0 Guide Chapter 5 Formatting Pages: Basics Page styles and related features Copyright This document is Copyright © 2018 by the LibreOffice Documentation Team. Contributors are listed below. You may distribute it and/or modify it under the terms of either the GNU General Public License (http://www.gnu.org/licenses/gpl.html), version 3 or later, or the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), version 4.0 or later. All trademarks within this guide belong to their legitimate owners. Contributors Jean Hollis Weber Bruce Byfield Gillian Pollack Acknowledgments This chapter is updated from previous versions of the LibreOffice Writer Guide. Contributors to earlier versions are: Jean Hollis Weber John A Smith Ron Faile Jr. Jamie Eby This chapter is adapted from Chapter 4 of the OpenOffice.org 3.3 Writer Guide. The contributors to that chapter are: Agnes Belzunce Ken Byars Daniel Carrera Peter Hillier-Brook Lou Iorio Sigrid Kronenberger Peter Kupfer Ian Laurenson Iain Roberts Gary Schnabl Janet Swisher Jean Hollis Weber Claire Wood Michele Zarri Feedback Please direct any comments or suggestions about this document to the Documentation Team’s mailing list: [email protected] Note Everything you send to a mailing list, including your email address and any other personal information that is written in the message, is publicly archived and cannot be deleted. Publication date and software version Published July 2018. Based on LibreOffice 6.0. Note for macOS users Some keystrokes and menu items are different on macOS from those used in Windows and Linux. The table below gives some common substitutions for the instructions in this book. -

Guidelines for Writing a Thesis Or Dissertation

GUIDELINES FOR WRITING A THESIS OR DISSERTATION CONTENTS: Guidelines for Writing a Thesis or Dissertation, Linda Childers Hon, Ph.D. Outline for Empirical Master’s Theses, Kurt Kent, Ph.D. How to Actually Complete A Thesis: Segmenting, Scheduling, and Rewarding, Kurt Kent, Ph.D. How to Make a Thesis Less Painful and More Satisfying (by Mickie Edwardson, Distinguished Professor of Telecommunication, Emeritus, ca. 1975), provided by Kurt Kent 2007-2008 Guidelines for Writing a Thesis or Dissertation Linda Childers Hon Getting Started 1. Most research begins with a question. Think about which topics and theories you are interested in and what you would like to know more about. Think about the topics and theories you have studied in your program. Is there some question you feel the body of knowledge in your field does not answer adequately? 2. Once you have a question in mind, begin looking for information relevant to the topic and its theoretical framework. Read everything you can--academic research, trade literature, and information in the popular press and on the Internet. 3. As you become well-informed about your topic and prior research on the topic, your knowledge should suggest a purpose for your thesis/dissertation. When you can articulate this purpose clearly, you are ready to write your prospectus/proposal. This document specifies the purpose of the study, significance of the study, a tentative review of the literature on the topic and its theoretical framework (a working bibliography should be attached), your research questions and/or hypotheses, and how you will collect and analyze your data (your proposed instrumentation should be attached). -

J-Beginning-Chapter-Books.Pdf

Children’s Juvenile Striker Assist by Jake Maddox Pewaukee Public Library Fiction Books (GR– P/Lexile 590) How to be a Perfect Person in These titles can by found in the Juvenile Fiction Collection Just Three Days by Stephen Manes Beginning organized alphabetically by the (GR– N/ Lexile 720) author’s last name. Judy Moody by Megan McDonald Chapter (GR– M/ Lexile 530) Ivy and Bean by Annie Barrows (GR– M/Lexile 510) Lulu by Hilary McKay Books (GR-N/Lexile 600-670) Franny K Stein by Jim Benton (GR– N/ Lexile 740-840) The Life of Ty: Penguin Problems by Lauren Myracle Man Out at First by Matt (GR– M/ Lexile 540) Christopher (GR– M/ Lexile 590) Down Girl and Sit: Smarter Jake Drake, Bully Buster Than Squirrels by Lucy Nolan by Andrew Clements (GR– O/ (GR– L/ Lexile 380) Lexile 460) Junie B. Jones by Barbara Park Third Grade Pet by Judy Cox (GR– M/ Lexile 310-410) (GR– N/ Lexile 320) Amber Brown by Paula Danziger (GR– N,O/ Lexile 630- For children moving 760) up from Early Readers Mercy Watson Thinks Like a Pig by Kate DiCamillo (GR– K/ to Chapter Books! Lexile 380) Princess Posey by Stephanie Greene (GR– L/ Lexile 310-390) The Year of Billy Miller Pewaukee Public Library by Kevin Henkes (GR- P/ Lexile 620) 210 Main Street Pewaukee, WI 53072 Horrible Harry by Suzy Kline (262) 691-5670 (GR– L, M/ Lexile 470-580) [email protected] Gooney Bird Greene by Lois www.pewaukeelibrary.org Lowry (GR– N/ Lexile 590) Check us out on Facebook.com! *Guided Reading levels (GR) and Children’s Series Books Kylie Jean by Marci Peschke Lexile levels are given for each title. -

Read-Aloud Chapter Books for Younger Children for Children Through 3 Rd Grade Remember to Choose a Story That You Will Also Enjoy

Read-Aloud Chapter Books for Younger Children rd for children through 3 grade Remember to choose a story that you will also enjoy The Wolves of Willoughby Chase by Joan Aiken: Surrounded by villains of the first order, brave Bonnie and gentle cousin Sylvia conquer all obstacles in this Victorian melodrama. Poppy by Avi: Poppy the deer mouse urges her family to move next to a field of corn big enough to feed them all forever, but Mr. Ocax, a terrifying owl, has other ideas. The Indian in the Cupboard by Lynne Reid Banks: A nine-year-old boy receives a plastic Indian, a cupboard, and a little key for his birthday and finds himself involved in adventure when the Indian comes to life in the cupboard and befriends him. Double Fudge by Judy Blume: His younger brother's obsession with money and the discovery of long-lost cousins Flora and Fauna provide many embarrassing moments for twelve-year-old Peter. The Mouse and the Motorcycle by Beverly Cleary: A reckless young mouse named Ralph makes friends with a boy in room 215 of the Mountain View Inn and discovers the joys of motorcycling. How to Train Your Dragon by Cressida Cowell : Chronicles the adventures and misadventures of Hiccup Horrendous Haddock the Third as he tries to pass the important initiation test of his Viking clan, the Tribe of the Hairy Hooligans, by catching and training a dragon. Understood Betsy by Dorothy Canfield Fisher: Timid and small for her age, nine- year-old Elizabeth Ann discovers her own abilities and gains a new perception of the world around her when she goes to live with relatives on a farm in Vermont. -

No. 25 a Secret Index—

a secret index— division leap no. 25 a secret index— Booksellers, publishers and researchers of the history of print culture. Collections purchased. Books found. Appraisals performed. Libraries built. divisionleap.com no. 25 83. 35. 59. 39. 39. 27. 30. 25. 21. 65. 48. 72. 6. contents a. Walter Benjamin—German Expressionism—Raubdrucke 17 b. Reproduction—Computing—Classification—Architecture 23 c. The Body—Tattooing—Incarceration—Crime—Sexuality 33 d. Social Movements—1968—Feminism—The SI & After 47 e. Music 57 f. Literature—Poetry—Periodicals 63 g. Film—Chris Marker 77 h. Art 85 i. Punk Zines 91 Additional images of all items available at divisionleap.com or by request. a. Walter Benjamin—German Expressionism—Raubdrucke 17 2. 1. 18 a. The Birth of Walter Benjamin’s Theory Heuber so messianically feels is near … ” of the Messianic McCole, analyzing this same letter, notes that this appears to be Benjamin’s first use of the term 1. [Victor Hueber] Die Organisierung der “Messianic” in his writings [McCole, p. 61]. The Intelligenz. Ein Aufruf. Zweite, erweiterte Auflage. idea would haunt Benjamin’s subsequent works Als Manuskript gedruckt. on history, and reach its conclusion in the second [Prague]: Druck H. Mercy, [1910]. 8vo, thesis in On the Concept of History, written just 107 pp, stab-stapled and glue bound into violet before his march into the mountains. “The past printed wraps. Front and back panels of wraps carries with it a secret index, by which it is referred detached but present, with the paper covering to its resurrection. There is an agreement and an the spine mostly perished. -

The Title Page Includes Five Elements: Title, Running Head, Author Byline, Institutional Affiliation, and Author Note

Adapted from “Top 10 APA Basics” by the Grace Abbott School of Social Work, UNO Top 10 APA Basics As of 7-15-2013, UNO Writing Center **Use this as a quick reference guide only. Use the APA Manual,6th Edition, as your authoritative guide. American Psychological Association. (2010). Publication manual of the th American Psychological Association (6 ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. An excellent resource: http://www.apastyle.org/learn/index.aspx 1) Font (p. 228) Times New Roman 12-point Correct spelling and grammar 2) Margins (p. 229) are always 1” on left, right, top and bottom important!! 3) Justification/Spacing (p. 229) Left-justified The entire paper is double-spaced, including block quotes and the Reference page Do not use the default settings; reset your paper to 0 pt. spacing and check the box “Don’t add space between paragraphs of the same style” (located on the paragraph dialog box on Microsoft Word) 4) Page Headings (p. 229-230) The title page includes five elements: title, running head, author byline, institutional affiliation, and author note. The running head is an abbreviated title in all capital letters, flush left in the header. It is a maximum of 50 characters. Page numbers are located in the upper right-hand corner of the page (in the header), 1” from the right, ½” from the top. Identify the title page with the number 1. Running head: MULTIPLE INTELLIGENCES 1 Multiple Intelligences: New Horizons in Theory and Practice Howard Gardner University of Nebraska at Omaha Adapted from “Top 10 APA Basics” by the Grace Abbott School of Social Work, UNO MULTIPLE INTELLIGENCES 2 5) Section Headings (p. -

How to Create and Maintain a Table of Contents

How to Create and Maintain a Table of Contents How to Create and Maintain a Table of Contents Version 0.2 First edition: January 2004 First English edition: January 2004 Contents Contents Overview........................................................................................................................................ iii About this guide..........................................................................................................................iii Conventions used in this guide................................................................................................... iii Copyright and trademark information.........................................................................................iii Feedback.....................................................................................................................................iii Acknowledgments...................................................................................................................... iv Modifications and updates..........................................................................................................iv Creating a table of contents.......................................................................................................... 1 Opening Writer's table of contents feature.................................................................................. 1 Using the Index/Table tab ...........................................................................................................2 Setting -

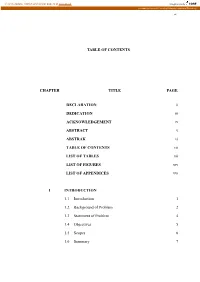

TABLE of CONTENTS CHAPTER TITLE PAGE DECLARATION Ii DEDICATION Iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Iv ABSTRACT V ABSTRAK Vi TABLE of CONTENTS Vi

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Universiti Teknologi Malaysia Institutional Repository vii TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER TITLE PAGE DECLARATION ii DEDICATION iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT iv ABSTRACT v ABSTRAK vi TABLE OF CONTENTS vii LIST OF TABLES xii LIST OF FIGURES xiv LIST OF APPENDICES xvi 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 Background of Problem 2 1.3 Statement of Problem 4 1.4 Objectives 5 1.5 Scopes 6 1.6 Summary 7 viii 2 LITERATURE REVIEW 2.1 Introduction 8 2.2 E-commerce credit 9 2.2.1 Credit 10 2.2.2 E-commerce 11 2.2.3 E-commerce Credit 15 2.3 E-commerce Credit Risk 17 2.4 Online-trading in E-commerce 18 2.4.1 The Characteristics of Online-trading 18 2.4.2 Online-consuming Model 21 2.5 C2C Credit Risk Analysis 24 2.5.1 C2C System Structure 25 2.5.2 C2C Characteristics 27 2.5.3 The Origin of C2C Credit Risk 29 2.6 The Construction of C2C Credit Evaluation System 32 2.6.1 The Analysis of C2C credit evaluation system 33 2.6.2 Case Study of TaoBao and E-bay 34 2.6.3 The Lacks of Current C2C Credit Evaluation 38 System 2.7 Summary 39 3 RESEARCH METHDOLOGY 3.1 Introduction 40 3.2 Project Methodology 41 3.2.1 Feasibility and Planning Phase 46 3.2.2 Requirement Analysis Phase 48 3.2.3 System Design Phase 49 3.2.4 System Build Phase 50 ix 3.2.5 System Testing and Evaluation Phase 51 3.3 Hardware and Software Requirements 52 3.3.1 Hardware Requirements 52 3.3.2 Software Requirements 53 3.4 Project Plan 55 4 DATA ANALYSIS 4.1 Introduction 56 4.2 Current system of TaoBao Company 57 4.3 Problem -

How to Page a Document in Microsoft Word

1 HOW TO PAGE A DOCUMENT IN MICROSOFT WORD 1– PAGING A WHOLE DOCUMENT FROM 1 TO …Z (Including the first page) 1.1 – Arabic Numbers (a) Click the “Insert” tab. (b) Go to the “Header & Footer” Section and click on “Page Number” drop down menu (c) Choose the location on the page where you want the page to appear (i.e. top page, bottom page, etc.) (d) Once you have clicked on the “box” of your preference, the pages will be inserted automatically on each page, starting from page 1 on. 1.2 – Other Formats (Romans, letters, etc) (a) Repeat steps (a) to (c) from 1.1 above (b) At the “Header & Footer” Section, click on “Page Number” drop down menu. (C) Choose… “Format Page Numbers” (d) At the top of the box, “Number format”, click the drop down menu and choose your preference (i, ii, iii; OR a, b, c, OR A, B, C,…and etc.) an click OK. (e) You can also set it to start with any of the intermediate numbers if you want at the “Page Numbering”, “Start at” option within that box. 2 – TITLE PAGE WITHOUT A PAGE NUMBER…….. Option A – …And second page being page number 2 (a) Click the “Insert” tab. (b) Go to the “Header & Footer” Section and click on “Page Number” drop down menu (c) Choose the location on the page where you want the page to appear (i.e. top page, bottom page, etc.) (d) Once you have clicked on the “box” of your preference, the pages will be inserted automatically on each page, starting from page 1 on. -

Human Rights Advocates Volume 47 Summer 2006

Human Rights Advocates Volume 47 Summer 2006 The Dedication of the Frank condemning apartheid in South Africa when the U.S. C. Newman International Congress already had imposed sanctions against that gov- ernment. Frank answered that the U.S. Executive Branch Human Rights Law Clinic is free to vote as it wants as long as its vote has no financial implications. This, noted Eya, was what helped him un- n April 17, 2006, USF School of Law hosted a derstand how the U.S. government works. Odedication ceremony to name the Frank C. New- Professor David Weissbrodt, a former student man International Human Rights Law Clinic. The ded- and co- author with Frank of the international law text- ication followed student presentations on their work at book used by numerous law schools, and former mem- the U.N. this Spring. It was made possible by the gener- ber of the U.N. Sub-Commission on Promotion and osity of Frances Newman, his wife, and Holly Newman, Protection of Human Rights wrote: his daughter. Ms. Newman made the following state- “Frank Newman was my teacher, mentor, co-au- ment for the occasion: thor, friend, and skiing partner. He inspired a generation “I know how greatly pleased – and honored – of human rights scholars and activists. Frank Newman Frank would have been by the advent of this new center. taught by word and example not only human rights law With gratitude, our daughter Holly and I look forward and legal analytical skills, but also how to be both a law- to the years ahead, assured that, with the expert guid- yer and a human being. -

WRITING YOUR FAMILY HISTORY a Guideline for Your Project

WRITING YOUR FAMILY HISTORY A Guideline for Your Project Old Buncombe County Genealogical Society P.O. Box 2122, Asheville, NC 28802 •828-253-1894 •www.obcgs.com If you are interested in genealogy and have conducted even the shortest of searches for a relative, you might have thought about how to organize the results into a useful format. One could write a report, an article for a journal or even set up a notebook to share with others, but a book might seem daunting. Many genealogists dream about writing a book on their family research, but do not know where to start. In 2012, OBCGS organized a working group to explore the steps needed to write a family history book. The group was able to organize their findings and put them all in one place to share with our members. The result is this guideline, a summary of the steps necessary to get your research ready for printing. I. THE ORGANIZING PROCESS – success is easier when you do some planning up front. a. Choose the Format – cookbook, photo album, genealogy narrative, etc. b. Choose the Scope – one family line descending from a distant ancestor; the grandparent’s story; the military service of a Revolutionary War soldier in the family including his family genealogy; etc. c. Choose a Plot or Theme – one way to make the book more interesting to a broader audience is to use a plot or theme throughout. Suggestions might be their immigration story; life after slavery; survival during the Great Depression; etc. d. Research the Time and Place – this provides more narrative for the reader and rounds out the family members’ experience so the reader understands what they went through to raise their family and survive.