From Carson Pirie Scott to City Target: a Case Study on the Adaptive Reuse of Louis Sullivan’S Historic Sullivan Center

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pittsfield Building 55 E

LANDMARK DESIGNATION REPORT Pittsfield Building 55 E. Washington Preliminary Landmarkrecommendation approved by the Commission on Chicago Landmarks, December 12, 2001 CITY OFCHICAGO Richard M. Daley, Mayor Departmentof Planning and Developement Alicia Mazur Berg, Commissioner Cover: On the right, the Pittsfield Building, as seen from Michigan Avenue, looking west. The Pittsfield Building's trademark is its interior lobbies and atrium, seen in the upper and lower left. In the center, an advertisement announcing the building's construction and leasing, c. 1927. Above: The Pittsfield Building, located at 55 E. Washington Street, is a 38-story steel-frame skyscraper with a rectangular 21-story base that covers the entire building lot-approximately 162 feet on Washington Street and 120 feet on Wabash Avenue. The Commission on Chicago Landmarks, whose nine members are appointed by the Mayor, was established in 1968 by city ordinance. It is responsible for recommending to the City Council that individual buildings, sites, objects, or entire districts be designated as Chicago Landmarks, which protects them by law. The Comm ission is staffed by the Chicago Department of Planning and Development, 33 N. LaSalle St., Room 1600, Chicago, IL 60602; (312-744-3200) phone; (312 744-2958) TTY; (312-744-9 140) fax; web site, http ://www.cityofchicago.org/ landmarks. This Preliminary Summary ofInformation is subject to possible revision and amendment during the designation proceedings. Only language contained within the designation ordinance adopted by the City Council should be regarded as final. PRELIMINARY SUMMARY OF INFORMATION SUBMITIED TO THE COMMISSION ON CHICAGO LANDMARKS IN DECEMBER 2001 PITTSFIELD BUILDING 55 E. -

Planners Guide to Chicago 2013

Planners Guide to Chicago 2013 2013 Lake Baha’i Glenview 41 Wilmette Temple Central Old 14 45 Orchard Northwestern 294 Waukegan Golf Univ 58 Milwaukee Sheridan Golf Morton Mill Grove 32 C O N T E N T S Dempster Skokie Dempster Evanston Des Main 2 Getting Around Plaines Asbury Skokie Oakton Northwest Hwy 4 Near the Hotels 94 90 Ridge Crawford 6 Loop Walking Tour Allstate McCormick Touhy Arena Lincolnwood 41 Town Center Pratt Park Lincoln 14 Chinatown Ridge Loyola Devon Univ 16 Hyde Park Peterson 14 20 Lincoln Square Bryn Mawr Northeastern O’Hare 171 Illinois Univ Clark 22 Old Town International Foster 32 Airport North Park Univ Harwood Lawrence 32 Ashland 24 Pilsen Heights 20 32 41 Norridge Montrose 26 Printers Row Irving Park Bensenville 32 Lake Shore Dr 28 UIC and Taylor St Addison Western Forest Preserve 32 Wrigley Field 30 Wicker Park–Bucktown Cumberland Harlem Narragansett Central Cicero Oak Park Austin Laramie Belmont Elston Clybourn Grand 43 Broadway Diversey Pulaski 32 Other Places to Explore Franklin Grand Fullerton 3032 DePaul Park Milwaukee Univ Lincoln 36 Chicago Planning Armitage Park Zoo Timeline Kedzie 32 North 64 California 22 Maywood Grand 44 Conference Sponsors Lake 50 30 Park Division 3032 Water Elmhurst Halsted Tower Oak Chicago Damen Place 32 Park Navy Butterfield Lake 4 Pier 1st Madison United Center 6 290 56 Illinois 26 Roosevelt Medical Hines VA District 28 Soldier Medical Ogden Field Center Cicero 32 Cermak 24 Michigan McCormick 88 14 Berwyn Place 45 31st Central Park 32 Riverside Illinois Brookfield Archer 35th -

Second Annual Report 1934

74th Congress, 1st Session House Document No: 31 SECOND ANNUAL REPORT of the FEDERAL HOME LOAN BANK BOARD covering operations of the FEDERAL HOME LOAN BANKS THE HOME OWNERS' LOAN CORPORATION THE FEDERAL SAVINGS AND LOAN DIVISION FEDERAL SAVINGS AND LOAN INSURANCE CORPORATION from the date of their creation through December 31, 1934 FEBRUARY 14, 1935.-Referred to the Committee on Banking and Currency and ordered to be printed with illustration UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: 1935 Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL FEDERAL HOME LOAN BANK BOARD, Washington, February 11, 195. SIR: Pursuant to the requirements of section 20 of the Federal Home Loan Bank Act, we have the honor to submit herewith the second annual report of the Federal Home Loan Bank Board covering operations for the year 1934 (a) of the Federal Home Loan Banks, (b) the Home Owners' Loan Corporation, (c) the Federal Savings and Loan Division, and (d) the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation from organization to December 31, 1934. JOHN H. FAHEY, Chairman. T. D. WEBB, W. F. STEVENSON, FRED W. CATLETT, H. E. HOAGLAND, Members. THE SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. iM Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis SECOND ANNUAL REPORT OF THE FEDERAL HOME LOAN BANK BOARD ON THE OPERATIONS OF THE FEDERAL HOME LOAN BANK SYSTEM FOR THE YEAR 1934 When the Federal Home Loan Bank System closed its 1933 opera tions December 31 it had 2,086 members, consisting mostly of building and loan, homestead associations, and cooperative banks who had subscribed for stock in the Corporation to the amount of $10,908,300. -

First Chicago School

FIRST CHICAGO SCHOOL JASON HALE, TONY EDWARDS TERRANCE GREEN ORIGINS In the 1880s Chicago created a group of architects whose work eventually had a huge effect on architecture. The early buildings of the First Chicago School like the Auditorium, “had traditional load-bearing walls” Martin Roche, William Holabird, and Louis Sullivan all played a huge role in the development of the first chicago school MATERIALS USED iron beams Steel Brick Stone Cladding CHARACTERISTICS The "Chicago window“ originated from this style of architecture They called this the commercial style because of the new tall buildings being created The windows and columns were changed to make the buildings look not as big FEATURES Steel-Frame Buildings with special cladding This material made big plate-glass window areas better and limited certain things as well The “Chicago Window” which was built using this style “combined the functions of light-gathering and natural ventilation” and create a better window DESIGN The Auditorium building was designed by Dankmar Adler and Louis Sullivan The Auditorium building was a tall building with heavy outer walls, and it was similar to the appearance of the Marshall Field Warehouse One of the most greatest features of the Auditorium building was “its massive raft foundation” DANKMAR ALDER Adler served in the Union Army during the Civil War Dankmar Adler played a huge role in the rebuilding much of Chicago after the Great Chicago Fire He designed many great buildings such as skyscrapers that brought out the steel skeleton through their outter design he created WILLIAM HOLABIRD He served in the United States Military Academy then moved to chicago He worked on architecture with O. -

Chicago No 16

CLASSICIST chicago No 16 CLASSICIST NO 16 chicago Institute of Classical Architecture & Art 20 West 44th Street, Suite 310, New York, NY 10036 4 Telephone: (212) 730-9646 Facsimile: (212) 730-9649 Foreword www.classicist.org THOMAS H. BEEBY 6 Russell Windham, Chairman Letter from the Editors Peter Lyden, President STUART COHEN AND JULIE HACKER Classicist Committee of the ICAA Board of Directors: Anne Kriken Mann and Gary Brewer, Co-Chairs; ESSAYS Michael Mesko, David Rau, David Rinehart, William Rutledge, Suzanne Santry 8 Charles Atwood, Daniel Burnham, and the Chicago World’s Fair Guest Editors: Stuart Cohen and Julie Hacker ANN LORENZ VAN ZANTEN Managing Editor: Stephanie Salomon 16 Design: Suzanne Ketchoyian The “Beaux-Arts Boys” of Chicago: An Architectural Genealogy, 1890–1930 J E A N N E SY LV EST ER ©2019 Institute of Classical Architecture & Art 26 All rights reserved. Teaching Classicism in Chicago, 1890–1930 ISBN: 978-1-7330309-0-8 ROLF ACHILLES ISSN: 1077-2922 34 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Frank Lloyd Wright and Beaux-Arts Design The ICAA, the Classicist Committee, and the Guest Editors would like to thank James Caulfield for his extraordinary and exceedingly DAVID VAN ZANTEN generous contribution to Classicist No. 16, including photography for the front and back covers and numerous photographs located throughout 43 this issue. We are grateful to all the essay writers, and thank in particular David Van Zanten. Mr. Van Zanten both contributed his own essay Frank Lloyd Wright and the Classical Plan and made available a manuscript on Charles Atwood on which his late wife was working at the time of her death, allowing it to be excerpted STUART COHEN and edited for this issue of the Classicist. -

Office Buildings of the Chicago School: the Restoration of the Reliance Building

Stephen J. Kelley Office Buildings of the Chicago School: The Restoration of the Reliance Building The American Architectural Hislorian Carl Condit wrote of exterior enclosure. These supporting brackets will be so ihe Reliance Building, "If any work of the structural arl in arranged as to permit an independent removal of any pari the nineteenth Century anticipated the future, it is this one. of the exterior lining, which may have been damaged by The building is the Iriumph of the structuralist and funclion- fire or otherwise."2 alist approach of the Chicago School. In its grace and air- Chicago architect William LeBaron Jenney is widely rec- iness, in the purity and exactitude of its proportions and ognized as the innovator of the application of the iron details, in the brilliant perfection of ils transparent eleva- frame and masonry curtain wall for skyscraper construc- tions, it Stands loday as an exciting exhibition of the poten- tion. The Home Insurance Building, completed in 1885, lial kinesthetic expressiveness of the structural art."' The exhibited the essentials of the fully-developed skyscraper Reliance Building remains today as the "swan song" of the on its main facades with a masonry curtain wall.' Span• Chicago School. This building, well known throughout the drei beams supported the exterior walls at the fourth, sixth, world and lisled on the US National Register of Historie ninth, and above the tenth levels. These loads were Irans- Places, is presenlly being restored. Phase I of this process ferred to stone pier footings via the metal frame wilhout which addresses the exterior building envelope was com- load-bearing masonry walls.'1 The strueture however had pleted in November of 1995. -

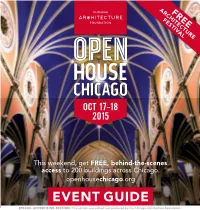

EVENT GUIDE SPECIAL ADVERTISING SECTION: This Section Was Edited and Produced by the Chicago Architecture Foundation

ARCHITECTUREFREE FESTIVAL This weekend, get FREE, behind-the-scenes access to 200 buildings across Chicago. openhousechicago.org EVENT GUIDE SPECIAL ADVERTISING SECTION: This section was edited and produced by the Chicago Architecture Foundation. 1 PRESENTED BY About the Chicago Architecture Foundation Five years ago, the Chicago to embark on a tour, workshops for Architecture Foundation (CAF) students, lectures for adults and decided to bring a city-wide festival of field trip groups gathered around architecture and design to Chicago— our 1,000-building scale model of the quintessential city of American Chicago. architecture. London originated the In addition to Open House Chicago, “Open House” concept more than 20 CAF is best known for our 85 different years ago, New York City had several Chicago-area tours, including the top- years under its belt and even Toronto ranked tour in the city: the Chicago produced a similar festival. By 2011, it Architecture Foundation River Cruise was Chicago’s time and Open House aboard Chicago’s First Lady Cruises. Chicago was born. Our 450 highly-trained volunteer CAF was founded in 1966. As a docents lead more than 6,000 walking, STS. VOLODYMYR & OLHA UKRAINIAN CATHOLIC CHURCH (P. 10) photo by Anne Evans nonprofit organization dedicated boat, bus and L train tours each year. to inspiring people to discover why CAF also offers exhibitions, public designed matters, CAF has grown programs and education activities Ten things to know about over the years to become a hub for for all ages. Open House Chicago learning about and participating in Learn more about CAF and our architecture and design. -

Hotel Recommendations

Hotel Recommendations The CTBUH recommends staying at one of the many downtown hotel options and taking a taxi or CTA Green Line train to and from the IIT campus. Most downtown hotels are about 10-15 minutes by taxi or Green Line train. 5-star Hotels 4-star Hotels Four Seasons Hotel Hard Rock Hotel Chicago 120 E. Delaware Pl, Chicago, IL 60611 230 N. Michigan Ave, Chicago, IL 60601 www.fourseasons.com/chicagofs/ www.hardrockhotelchicago.com/ Located across from the John Hancock Building at the north end of the Magnicent Mile, this Located on Michigan Avenue in the 1929 Carbide & Carbon Building with Art Deco hotel features unrivalled guest-room views of Lake Michigan and the city skyline. furnishings, just steps from the Loop and Millennium Park. Park Hyatt Chicago Hotel Burnham 800 N Michigan Ave, Chicago, IL 60611 1 West Washington, Chicago, IL 60602 http://parkchicago.hyatt.com/ www.burnhamhotel.com/ Located at Water Tower Square, across from the John Hancock building, and includes an Located in the Reliance Building, a National Historic Landmark built in 1895 by Burnham and award winning restaurant and a private art gallery. Root as one of the rst skyscrapers, this boutique hotel is located in the heart of the loop. Trump International Hotel & Tower Hotel Sax Chicago 401 N. Wabash Avenue, Chicago, IL 60611 333 N. Dearborn St, Chicago, IL 60654 www.trumpchicagohotel.com/ www.hotelsaxchicago.com/ The 2nd tallest building in the US, the Trump showcases panoramic views of the Chicago Located within the classic Marina City Towers in the heart of downtown, this chic boutique skyline and Lake Michigan. -

Mundelein College Photograph Collection, 1930-1993, Undated

Women and Leadership Archives Loyola University Chicago Mundelein College Photograph Collection, 1930-1993, undated Preliminary Finding Aid Creator: Mundelein College Extent: TBD Language: English Repository: Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago Administrative Information Access Restrictions: None Usage Restrictions: Copyright of the material was transferred to the Women and Leadership Archives (WLA). Preferred Citation: Identification of item, date, box #, folder #, Mundelein College Photograph Collection, Women and Leadership Archives, Loyola University Chicago. Provenance: The Mundelein College Photograph Collection was transferred to the WLA upon its founding in 1994. Processing Information: The Women and Leadership Archives received the Mundelein College Photograph Collection from the collection maintained in the college archives. A project to reprocess and digitize the photograph collection began in 2018 and is ongoing. Separations: None See Also: A portion of the collection is digitized and available at luc.access.preservica.edu. Mundelein College Paper Records, Women and Leadership Archives. Administrative History Mundelein College was founded by the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary (BVMs) in response to a call by Cardinal George Mundelein for a Catholic women’s college on the North Side of Chicago. For 60 years, Mundelein College offered its students a comprehensive Catholic liberal arts education. The women who were educated at Mundelein came from many ethnic and socio-economic groups and were often the first females in their families to attend college. The college was led through many changes and social movements in the Catholic Church and nation by renowned educator Sister Ann Ida Gannon, BVM, who served as president from 1957 to 1975. -

2012 HED Annual Report SCR

CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT 4 A. Finkl & Sons Co. 5 Hyatt Place at Harper Court 6 Rush University Medical Center 7 Mariano’s Fresh Market 8 Hillshire Brands 9 Costco 10 Morgan Street CTA Station 11 Shops & Lofts at 47 12 Kroc Corps. Community Center 13 Former 17th District Police Station 14 Jones College Prep 15 Pete’s Fresh Market 16 Small Business Improvement Fund 17 TIF Works 17 AFFORDABLE HOUSING 18 Bronzeville Senior Apartments 19 Home for New Moms 20 Diplomat Hotel 21 Bronzeville Artists Lofts 22 All Saints Residence 23 Park Douglas I 24 Lakefront Phase II 25 Oakwood Shores Terrace Apartments 26 Park Boulevard IIA 27 Woodlawn Center North 28 Naomi & Sylvester Smith Senior Living Center 29 Senior Suites of Midway Village 30 Chicago Low-Income Housing Trust Fund 31 Renaissance Apartments 32 Neighborhood Stabilization Program 33 Micro-Market Recovery Program 33 PLANNING AND ZONING 34 Sullivan Center 35 Walgreens 36 Randolph Tower 37 Wrigley Building 38 Continental Center 39 Pioneer Trust & Savings Bank 40 DuSable High School 41 Planned Development Designations 42 Palmisano Park 44 River Point 45 Clark Park Boat House 46 Ping Tom Park Boat House 47 Perry Street Farm 48 Northwest Highway & Wright Business Park Industrial Corridors 49 DEPARTMENT AGGREGATES 50 City of Chicago Department of Housing and Economic Development Andrew J. Mooney, Commissioner Aarti Kotak, Economic Development Deputy Commissioner Lawrence Grisham, Housing Deputy Commissioner Patti Scudiero, Planning and Zoning Deputy Commissioner Communications and Outreach Division 121 N. LaSalle St. #1000 Chicago, IL 60602 (312) 744-4190 www.cityofchicago.org/hed February 2013 Rahm Emanuel, Mayor INTRODUCTION The “Project Highlights” booklet is an overview of Department of Housing and Eco- nomic Development (HED) projects that were either initiated or completed between January and December of 2012. -

List of Illinois Recordations Under HABS, HAER, HALS, HIBS, and HIER (As of April 2021)

List of Illinois Recordations under HABS, HAER, HALS, HIBS, and HIER (as of April 2021) HABS = Historic American Buildings Survey HAER = Historic American Engineering Record HALS = Historic American Landscapes Survey HIBS = Historic Illinois Building Survey (also denotes the former Illinois Historic American Buildings Survey) HIER = Historic Illinois Engineering Record (also denotes the former Illinois Historic American Engineering Record) Adams County • Fall Creek Station vicinity, Fall Creek Bridge (HABS IL-267) • Meyer, Lock & Dam 20 Service Bridge Extension Removal (HIER) • Payson, Congregational Church, Park Drive & State Route 96 (HABS IL-265) • Payson, Congregational Church Parsonage (HABS IL-266) • Quincy, Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad, Freight Office, Second & Broadway Streets (HAER IL-10) • Quincy, Ernest M. Wood Office and Studio, 126 North Eighth Street (HABS IL-339) • Quincy, Governor John Wood House, 425 South Twelfth Street (HABS IL-188) • Quincy, Illinois Soldiers and Sailors’ Home (Illinois Veterans’ Home) (HIBS A-2012-1) • Quincy, Knoyer Farmhouse (HABS IL-246) • Quincy, Quincy Civic Center/Blocks 28 & 39 (HIBS A-1991-1) • Quincy, Quincy College, Francis Hall, 1800 College Avenue (HABS IL-1181) • Quincy, Quincy National Cemetery, Thirty-sixth and Maine Streets (HALS IL-5) • Quincy, St. Mary Hospital, 1415 Broadway (HIBS A-2017-1) • Quincy, Upper Mississippi River 9-Foot Channel Project, Lock & Dam No. 21 (HAER IL-30) • Quincy, Villa Kathrine, 532 Gardner Expressway (HABS IL-338) • Quincy, Washington Park (buildings), Maine, Fourth, Hampshire, & Fifth Streets (HABS IL-1122) Alexander County • Cairo, Cairo Bridge, spanning Ohio River (HAER IL-36) • Cairo, Peter T. Langan House (HABS IL-218) • Cairo, Store Building, 509 Commercial Avenue (HABS IL-25-21) • Fayville, Keating House, U.S. -

Kansas City, Kansas CLG Phase 2 Survey

KANSAS CITY, KANSAS CERTIFIED LOCAL GOVERNMENT PROGRAM HISTORICAL AND ARCHITECTURAL SURVEY KERR'S PARK, ARICKAREE, AND WESTHEIGHT MANOR NO. 5 • ST. PETER'S PARISH •• KANSAS CITY UNIVERSITY CERTIFIED LOCAL GOVERNMENT PROGRAM FY 1987 October 1, 1987 - August 31, 1988 GRANT NO. 20-87-20018-006 HISTORIC INVENTORY - PHASE 2 SURVEY KANSAS CITY, KANSAS Prepared by Cydney Miiistein Architectural and Art Hlstorlcal Research, Kansas City, Missouri and Kansas City, Kansas City Planning Division 1990 THE CITY OF KANSAS CITY, KANSAS' Joseph E. Steineger, Jr., Mayor Chester C. Owens, Jr., Councilman First District Carol Marinovich, Councilwoman Second District Richard A. Ruiz, Councilman Third District Ronald D. Mears, Councilman Fourth District Frank Corbett, Councilman Fifth District Wm. H. (Bill) Young, Councilman Sixth District KANSAS CITY, KANSAS LANDMARKS COMMISSION Charles Van Middlesworth, Chairman George Breidenthal Gene Buchanan Ray Byers Virginia Hubbard James R. McField Mary Murguia KANSAS CITY, KANSAS CERTIFIED LOCAL GOVERNMENT PHASE 2 SURVEY INTRODUCTION The City of Kansas City, Kansas contracted for an historical and arch i tectura1 survey of three neighborhoods in Kansas City, Kansas, including Kerr's Park, Arickaree, and Westheight Manor No. 5; St. Peter's Parish; and a selected number of individual structures in the area known as the Kansas City University neighborhood. The survey, the subject of this final report and the second to be carried out in Kansas City under a Certified Lo ca 1 Government grant, commenced in October, 1987 and was comp 1eted by August 31, 1988. It has been financed in part with Federal funds from the National Park Service, a division of the United States Department of the Interior, and administered by the Kansas State Historical Society.