Forktail 30 (2014): 28–33

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Can Sexual Selection Theory Inform Genetic Management of Captive Populations? a Review Remi� Charge,� 1 Celine� Teplitsky,2 Gabriele Sorci3 and Matthew Low4

Evolutionary Applications Evolutionary Applications ISSN 1752-4571 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Can sexual selection theory inform genetic management of captive populations? A review Remi Charge, 1 Celine Teplitsky,2 Gabriele Sorci3 and Matthew Low4 1 Department of Biological and Environmental Science, Centre of Excellence in Biological Interactions, University of Jyvaskyl€ a,€ Jyvaskyl€ a,€ Finland 2 Centre d’Ecologie et de Sciences de la Conservation UMR 7204 CNRS/MNHN/UPMC, Museum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France 3 Biogeosciences, UMR CNRS 6282, Universite de Bourgogne, Dijon, France 4 Department of Ecology, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden Keywords Abstract conservation biology, evolutionary theory, sexual selection. Captive breeding for conservation purposes presents a serious practical challenge because several conflicting genetic processes (i.e., inbreeding depression, random Correspondence genetic drift and genetic adaptation to captivity) need to be managed in concert Remi Charge Department of Biological and to maximize captive population persistence and reintroduction success probabil- Environmental Science, Centre of Excellence in ity. Because current genetic management is often only partly successful in achiev- Biological Interactions, University of Jyvaskyl€ a,€ ing these goals, it has been suggested that management insights may be found in P.O Box 35, Jyvaskyl€ a,€ 40014, Finland. Tel.: 358(0)40 805 3852; sexual selection theory (in particular, female mate choice). We review the theo- fax: 358(0)1 461 7239; retical and empirical literature and consider how female mate choice might influ- e-mail: remi.r.charge@jyu.fi ence captive breeding in the context of current genetic guidelines for different sexual selection theories (i.e., direct benefits, good genes, compatible genes, sexy Received: 28 February 2014 sons). -

A Complete Species-Level Molecular Phylogeny For

Author's personal copy Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 47 (2008) 251–260 www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev A complete species-level molecular phylogeny for the ‘‘Eurasian” starlings (Sturnidae: Sturnus, Acridotheres, and allies): Recent diversification in a highly social and dispersive avian group Irby J. Lovette a,*, Brynn V. McCleery a, Amanda L. Talaba a, Dustin R. Rubenstein a,b,c a Fuller Evolutionary Biology Program, Laboratory of Ornithology, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14950, USA b Department of Neurobiology and Behavior, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14850, USA c Department of Integrative Biology and Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA Received 2 August 2007; revised 17 January 2008; accepted 22 January 2008 Available online 31 January 2008 Abstract We generated the first complete phylogeny of extant taxa in a well-defined clade of 26 starling species that is collectively distributed across Eurasia, and which has one species endemic to sub-Saharan Africa. Two species in this group—the European starling Sturnus vulgaris and the common Myna Acridotheres tristis—now occur on continents and islands around the world following human-mediated introductions, and the entire clade is generally notable for being highly social and dispersive, as most of its species breed colonially or move in large flocks as they track ephemeral insect or plant resources, and for associating with humans in urban or agricultural land- scapes. Our reconstructions were based on substantial mtDNA (4 kb) and nuclear intron (4 loci, 3 kb total) sequences from 16 species, augmented by mtDNA NDII gene sequences (1 kb) for the remaining 10 taxa for which DNAs were available only from museum skin samples. -

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with Birds Observed Off-Campus During BIOL3400 Field Course

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with birds observed off-campus during BIOL3400 Field course Photo Credit: Talton Cooper Species Descriptions and Photos by students of BIOL3400 Edited by Troy A. Ladine Photo Credit: Kenneth Anding Links to Tables, Figures, and Species accounts for birds observed during May-term course or winter bird counts. Figure 1. Location of Environmental Studies Area Table. 1. Number of species and number of days observing birds during the field course from 2005 to 2016 and annual statistics. Table 2. Compilation of species observed during May 2005 - 2016 on campus and off-campus. Table 3. Number of days, by year, species have been observed on the campus of ETBU. Table 4. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during the off-campus trips. Table 5. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during a winter count of birds on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Table 6. Species observed from 1 September to 1 October 2009 on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Alphabetical Listing of Birds with authors of accounts and photographers . A Acadian Flycatcher B Anhinga B Belted Kingfisher Alder Flycatcher Bald Eagle Travis W. Sammons American Bittern Shane Kelehan Bewick's Wren Lynlea Hansen Rusty Collier Black Phoebe American Coot Leslie Fletcher Black-throated Blue Warbler Jordan Bartlett Jovana Nieto Jacob Stone American Crow Baltimore Oriole Black Vulture Zane Gruznina Pete Fitzsimmons Jeremy Alexander Darius Roberts George Plumlee Blair Brown Rachel Hastie Janae Wineland Brent Lewis American Goldfinch Barn Swallow Keely Schlabs Kathleen Santanello Katy Gifford Black-and-white Warbler Matthew Armendarez Jordan Brewer Sheridan A. -

The Relationships of the Starlings (Sturnidae: Sturnini) and the Mockingbirds (Sturnidae: Mimini)

THE RELATIONSHIPS OF THE STARLINGS (STURNIDAE: STURNINI) AND THE MOCKINGBIRDS (STURNIDAE: MIMINI) CHARLESG. SIBLEYAND JON E. AHLQUIST Departmentof Biologyand PeabodyMuseum of Natural History,Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06511 USA ABSTRACT.--OldWorld starlingshave been thought to be related to crowsand their allies, to weaverbirds, or to New World troupials. New World mockingbirdsand thrashershave usually been placed near the thrushesand/or wrens. DNA-DNA hybridization data indi- cated that starlingsand mockingbirdsare more closelyrelated to each other than either is to any other living taxon. Some avian systematistsdoubted this conclusion.Therefore, a more extensiveDNA hybridizationstudy was conducted,and a successfulsearch was made for other evidence of the relationshipbetween starlingsand mockingbirds.The resultssup- port our original conclusionthat the two groupsdiverged from a commonancestor in the late Oligoceneor early Miocene, about 23-28 million yearsago, and that their relationship may be expressedin our passerineclassification, based on DNA comparisons,by placing them as sistertribes in the Family Sturnidae,Superfamily Turdoidea, Parvorder Muscicapae, Suborder Passeres.Their next nearest relatives are the members of the Turdidae, including the typical thrushes,erithacine chats,and muscicapineflycatchers. Received 15 March 1983, acceptedI November1983. STARLINGS are confined to the Old World, dine thrushesinclude Turdus,Catharus, Hylocich- mockingbirdsand thrashersto the New World. la, Zootheraand Myadestes.d) Cinclusis -

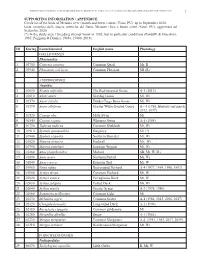

1 ID Euring Latin Binomial English Name Phenology Galliformes

BIRDS OF METAURO RIVER: A GREAT ORNITHOLOGICAL DIVERSITY IN A SMALL ITALIAN URBANIZING BIOTOPE, REQUIRING GREATER PROTECTION 1 SUPPORTING INFORMATION / APPENDICE Check list of the birds of Metauro river (mouth and lower course / Fano, PU), up to September 2020. Lista completa delle specie ornitiche del fiume Metauro (foce e basso corso /Fano, PU), aggiornata ad Settembre 2020. (*) In the study area 1 breeding attempt know in 1985, but in particolar conditions (Pandolfi & Giacchini, 1985; Poggiani & Dionisi, 1988a, 1988b, 2019). ID Euring Latin binomial English name Phenology GALLIFORMES Phasianidae 1 03700 Coturnix coturnix Common Quail Mr, B 2 03940 Phasianus colchicus Common Pheasant SB (R) ANSERIFORMES Anatidae 3 01690 Branta ruficollis The Red-breasted Goose A-1 (2012) 4 01610 Anser anser Greylag Goose Mi, Wi 5 01570 Anser fabalis Tundra/Taiga Bean Goose Mi, Wi 6 01590 Anser albifrons Greater White-fronted Goose A – 4 (1986, february and march 2012, 2017) 7 01520 Cygnus olor Mute Swan Mi 8 01540 Cygnus cygnus Whooper Swan A-1 (1984) 9 01730 Tadorna tadorna Common Shelduck Mr, Wi 10 01910 Spatula querquedula Garganey Mr (*) 11 01940 Spatula clypeata Northern Shoveler Mr, Wi 12 01820 Mareca strepera Gadwall Mr, Wi 13 01790 Mareca penelope Eurasian Wigeon Mr, Wi 14 01860 Anas platyrhynchos Mallard SB, Mr, W (R) 15 01890 Anas acuta Northern Pintail Mi, Wi 16 01840 Anas crecca Eurasian Teal Mr, W 17 01960 Netta rufina Red-crested Pochard A-4 (1977, 1994, 1996, 1997) 18 01980 Aythya ferina Common Pochard Mr, W 19 02020 Aythya nyroca Ferruginous -

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species Are Listed in Order of First Seeing Them ** H = Heard Only

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species are listed in order of first seeing them ** H = Heard Only July 6th 7th 8th 9th 10th 11th 12th 13th 14th 15th 16th 17th Mute Swan Cygnus olor X X X X X X X X Whopper Swan Cygnus cygnus X X X X Greylag Goose Anser anser X X X X X Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis X X X Tufted Duck Aythya fuligula X X X X Common Eider Somateria mollissima X X X X X X X X Common Goldeneye Bucephala clangula X X X X X X Red-breasted Merganser Mergus serrator X X X X X Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo X X X X X X X X X X Grey Heron Ardea cinerea X X X X X X X X X Western Marsh Harrier Circus aeruginosus X X X X White-tailed Eagle Haliaeetus albicilla X X X X Eurasian Coot Fulica atra X X X X X X X X Eurasian Oystercatcher Haematopus ostralegus X X X X X X X Black-headed Gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus X X X X X X X X X X X X European Herring Gull Larus argentatus X X X X X X X X X X X X Lesser Black-backed Gull Larus fuscus X X X X X X X X X X X X Great Black-backed Gull Larus marinus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common/Mew Gull Larus canus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Tern Sterna hirundo X X X X X X X X X X X X Arctic Tern Sterna paradisaea X X X X X X X Feral Pigeon ( Rock) Columba livia X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Wood Pigeon Columba palumbus X X X X X X X X X X X Eurasian Collared Dove Streptopelia decaocto X X X Common Swift Apus apus X X X X X X X X X X X X Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica X X X X X X X X X X X Common House Martin Delichon urbicum X X X X X X X X White Wagtail Motacilla alba X X -

Birdwatching Bingo Identification Sheet Hey Everyone! I Hope You Have Fun Playing Birdwatching Bingo with Your Family

Birdwatching Bingo Identification Sheet Hey Everyone! I hope you have fun playing Birdwatching Bingo with your family. You can even share it with friends and do it over social media. To help you on your adventure, here is an identification sheet with all the different birds listed on your bingo card. With the help of this sheet and some binoculars, you will be on your way to becoming a fantastic birdwatcher. Most of these birds you can see visiting a birdfeeder, but some you might have to go on a walk and look for with a parent. To play, download and print the bingo cards for each player. Using pennies, pieces of paper, or even a pencil, mark the card when you see and identify the different birds. Don’t be frustrated if you don’t finish the game in one sitting, this game might be completed over a couple days. A great tool to help with IDing birds is the app MERLIN. This is a free bird ID app for your phone from the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology. The website, www.allaboutbirds.org, is a great source too. Blue Jay - Scientific Name: Cyanocitta cristata - Identifiable Markings: o Blue above, light grey below. Black and white markings on wings and tail. Larger than a robin, smaller than a crow. Crest and long tail. - Photo: Females/Males Look Similar Brown-headed Cowbird - Scientific Name: Molothrus ater - Identifiable Markings: o Stout bill. Short tail and stocky body. Males are glossy black with chocolate brown head. Females are grey-brown overall, without bold streaks, but slightly paler throat. -

Bontebok Birds

Birds recorded in the Bontebok National Park 8 Little Grebe 446 European Roller 55 White-breasted Cormorant 451 African Hoopoe 58 Reed Cormorant 465 Acacia Pied Barbet 60 African Darter 469 Red-fronted Tinkerbird * 62 Grey Heron 474 Greater Honeyguide 63 Black-headed Heron 476 Lesser Honeyguide 65 Purple Heron 480 Ground Woodpecker 66 Great Egret 486 Cardinal Woodpecker 68 Yellow-billed Egret 488 Olive Woodpecker 71 Cattle Egret 494 Rufous-naped Lark * 81 Hamerkop 495 Cape Clapper Lark 83 White Stork n/a Agulhas Longbilled Lark 84 Black Stork 502 Karoo Lark 91 African Sacred Ibis 504 Red Lark * 94 Hadeda Ibis 506 Spike-heeled Lark 95 African Spoonbill 507 Red-capped Lark 102 Egyptian Goose 512 Thick-billed Lark 103 South African Shelduck 518 Barn Swallow 104 Yellow-billed Duck 520 White-throated Swallow 105 African Black Duck 523 Pearl-breasted Swallow 106 Cape Teal 526 Greater Striped Swallow 108 Red-billed Teal 529 Rock Martin 112 Cape Shoveler 530 Common House-Martin 113 Southern Pochard 533 Brown-throated Martin 116 Spur-winged Goose 534 Banded Martin 118 Secretarybird 536 Black Sawwing 122 Cape Vulture 541 Fork-tailed Drongo 126 Black (Yellow-billed) Kite 547 Cape Crow 127 Black-shouldered Kite 548 Pied Crow 131 Verreauxs' Eagle 550 White-necked Raven 136 Booted Eagle 551 Grey Tit 140 Martial Eagle 557 Cape Penduline-Tit 148 African Fish-Eagle 566 Cape Bulbul 149 Steppe Buzzard 572 Sombre Greenbul 152 Jackal Buzzard 577 Olive Thrush 155 Rufous-chested Sparrowhawk 582 Sentinel Rock-Thrush 158 Black Sparrowhawk 587 Capped Wheatear -

Landscape Factors That Influence European Starling (Sturnus Vulgaris) Nest Box Occupancy at NASA Plum Brook Station (PBS), Erie County, Ohio, USA

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff U.S. Department of Agriculture: Animal and Publications Plant Health Inspection Service 9-2019 Landscape Factors that Influence urE opean Starling (Sturnus vulgaris) Nest Box Occupancy at NASA Plum Brook Station (PBS), Erie County, Ohio, USA Morgan Pfeiffer U.S. Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, Wildlife Services, National Wildlife Research Center, [email protected] Thomas W. Seamans U.S. Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, Wildlife Services, National Wildlife Research Center Bruce N. Buckingham U.S. Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, Wildlife Services, National Wildlife Research Center BrFollowadle ythis F. Blackwelland additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_usdanwrc U.S. P Deparart of tmentthe Natur of Agricultural Resoure,ces Animal and Conser and Plantvation Health Commons Inspection, Natur Seral vice,Resour Wildlifces eManagement Services, National and Wildlife Research Center Policy Commons, Other Environmental Sciences Commons, Other Veterinary Medicine Commons, Population Biology Commons, Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons, Veterinary Infectious Diseases Commons, Veterinary Microbiology and Immunobiology Commons, Veterinary Preventive Medicine, Epidemiology, and Public Health Commons, and the Zoology Commons Pfeiffer, Morgan; Seamans, Thomas W.; Buckingham, Bruce N.; and Blackwell, Bradley F., "Landscape Factors that Influence urE opean Starling (Sturnus vulgaris) Nest Box Occupancy at NASA Plum Brook Station (PBS), Erie County, Ohio, USA" (2019). USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff Publications. 2297. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_usdanwrc/2297 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. -

Ornamentation, Behavior, and Maternal Effects in the Female Northern Cardinal

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Master's Theses Summer 8-2011 Ornamentation, Behavior, and Maternal Effects in the Female Northern Cardinal Caitlin Winters University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses Part of the Biology Commons, and the Ornithology Commons Recommended Citation Winters, Caitlin, "Ornamentation, Behavior, and Maternal Effects in the Female Northern Cardinal" (2011). Master's Theses. 240. https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses/240 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi ORNAMENTATION, BEHAVIOR, AND MATERNAL EFFECTS IN THE FEMALE NORTHERN CARDINAL by Caitlin Winters A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Approved: _Jodie M. Jawor_____________________ Director _Frank R. Moore_____________________ _Robert H. Diehl_____________________ _Susan A. Siltanen____________________ Dean of the Graduate School August 2011 ABSTRACT ORNAMENTATION, BEHAVIOR, AND MATERNAL EFFECTS IN THE FEMALE NORTHERN CARDINAL by Caitlin Winters August 2011 This study seeks to understand the relationship between ornamentation, maternal effects, and behavior in the female Northern Cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis). Female birds possess ornaments that indicate a number of important known aspects of quality and are usually costly to maintain. However, the extent to which female specific traits, such as maternal effects, are indicated is less clear. It is predicted by the Good Parent Hypothesis that this information should be displayed through intraspecific signal communication. -

Are European Starlings Breeding in the Azores Archipelago Genetically Distinct from Birds Breeding in Mainland Europe? Verónica C

Are European starlings breeding in the Azores archipelago genetically distinct from birds breeding in mainland Europe? Verónica C. Neves, Kate Griffiths, Fiona R. Savory, Robert W. Furness, Barbara K. Mable To cite this version: Verónica C. Neves, Kate Griffiths, Fiona R. Savory, Robert W. Furness, Barbara K. Mable. Are European starlings breeding in the Azores archipelago genetically distinct from birds breeding in mainland Europe?. European Journal of Wildlife Research, Springer Verlag, 2009, 56 (1), pp.95-100. 10.1007/s10344-009-0316-x. hal-00535248 HAL Id: hal-00535248 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00535248 Submitted on 11 Nov 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Eur J Wildl Res (2010) 56:95–100 DOI 10.1007/s10344-009-0316-x SHORT COMMUNICATION Are European starlings breeding in the Azores archipelago genetically distinct from birds breeding in mainland Europe? Verónica C. Neves & Kate Griffiths & Fiona R. Savory & Robert W. Furness & Barbara K. Mable Received: 6 May 2009 /Revised: 5 August 2009 /Accepted: 11 August 2009 /Published online: 29 August 2009 # Springer-Verlag 2009 Abstract The European starling (Sturnus vulgaris) has Keywords Azores . -

Niche Analysis and Conservation of Bird Species Using Urban Core Areas

sustainability Article Niche Analysis and Conservation of Bird Species Using Urban Core Areas Vasilios Liordos 1,* , Jukka Jokimäki 2 , Marja-Liisa Kaisanlahti-Jokimäki 2, Evangelos Valsamidis 1 and Vasileios J. Kontsiotis 1 1 Department of Forest and Natural Environment Sciences, International Hellenic University, 66100 Drama, Greece; [email protected] (E.V.); [email protected] (V.J.K.) 2 Arctic Centre, University of Lapland, 96101 Rovaniemi, Finland; jukka.jokimaki@ulapland.fi (J.J.); marja-liisa.kaisanlahti@ulapland.fi (M.-L.K.-J.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Knowing the ecological requirements of bird species is essential for their successful con- servation. We studied the niche characteristics of birds in managed small-sized green spaces in the urban core areas of southern (Kavala, Greece) and northern Europe (Rovaniemi, Finland), during the breeding season, based on a set of 16 environmental variables and using Outlying Mean Index, a multivariate ordination technique. Overall, 26 bird species in Kavala and 15 in Rovaniemi were recorded in more than 5% of the green spaces and were used in detailed analyses. In both areas, bird species occupied different niches of varying marginality and breadth, indicating varying responses to urban environmental conditions. Birds showed high specialization in niche position, with 12 species in Kavala (46.2%) and six species in Rovaniemi (40.0%) having marginal niches. Niche breadth was narrower in Rovaniemi than in Kavala. Species in both communities were more strongly associated either with large green spaces located further away from the city center and having a high vegetation cover (urban adapters; e.g., Common Chaffinch (Fringilla coelebs), European Greenfinch (Chloris Citation: Liordos, V.; Jokimäki, J.; chloris Cyanistes caeruleus Kaisanlahti-Jokimäki, M.-L.; ), Eurasian Blue Tit ( )) or with green spaces located closer to the city center Valsamidis, E.; Kontsiotis, V.J.