Seaweed Potential in the Animal Feed: a Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nutrient Bioextraction L

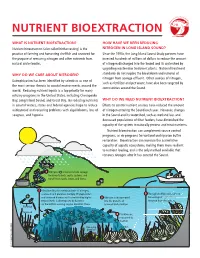

soun nd d s sla tu i d g y n o NUTRIENT BIOEXTRACTION l WHAT IS NUTRIENT BIOEXTRACTION? HOW HAVE WE BEEN REDUCING Nutrient bioextraction (also called bioharvesting) is the NITROGEN IN LONG ISLAND SOUND? practice of farming and harvesting shellfish and seaweed for Since the 1990s, the Long Island Sound Study partners have the purpose of removing nitrogen and other nutrients from invested hundreds of millions of dollars to reduce the amount natural water bodies. of nitrogen discharged into the Sound and its watershed by upgrading wastewater treatment plants. National treatment WHY DO WE CARE ABOUT NITROGEN? standards do not require the breakdown and removal of nitrogen from sewage effluent. Other sources of nitrogen, Eutrophication has been identified by scientists as one of such as fertilizer and pet waste, have also been targeted by the most serious threats to coastal environments around the communities around the Sound. world. Reducing nutrient inputs is a top priority for many estuary programs in the United States, including Chesapeake Bay, Long Island Sound, and Great Bay. By reducing nutrients WHY DO WE NEED NUTRIENT BIOEXTRACTION? in coastal waters, states and federal agencies hope to reduce Efforts to control nutrient sources have reduced the amount widespread and recurring problems with algal blooms, loss of of nitrogen entering the Sound each year. However, changes seagrass, and hypoxia. in the Sound and its watershed, such as wetland loss and decreased populations of filter feeders, have diminished the capacity of the system to naturally process and treat nutrients. Nutrient bioextraction can complement source control programs, as do programs for wetland and riparian buffer restoration. -

Revision of Herbarium Specimens of Freshwater Enteromorpha-Like Ulva (Ulvaceae, Chlorophyta) Collected from Central Europe During the Years 1849–1959

Phytotaxa 218 (1): 001–029 ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) www.mapress.com/phytotaxa/ PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2015 Magnolia Press Article ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.218.1.1 Revision of herbarium specimens of freshwater Enteromorpha-like Ulva (Ulvaceae, Chlorophyta) collected from Central Europe during the years 849–959 ANDRZEJ S. RYBAK Department of Hydrobiology, Institute of Environmental Biology, Faculty of Biology, Adam Mickiewicz University, Umultowska 89, PL61 – 614 Poznań, Poland. [email protected] Abstract This paper presents results concerning the taxonomic revision of Ulva taxa originating from herbarium specimens dating back to 1849–1959. A staining and softening mixture was applied to allow a detailed morphometric analysis of thalli and cells and to detect many morphological details. The study focused on individuals collected exclusively from inland water ecosystems (having no contact with sea water). Detailed analysis concerned the following items: structures of thalli and cells, number of pyrenoids per cell, configuration of cells inside the thallus, occurrence or not of branching thallus, shapes of apical cells, and shape of chromatophores. The objective of the study was to confirm the initial identifications of specimens of Ulva held in herbaria. The study sought to determine whether saltwater species of the genus Ulva, e.g., Ulva compressa and U. intestinalis, could have been found in European freshwater ecosystems in 19th and 20th centuries. Moreover, the paper presents a method for the initial treatment of voucher specimens for viewing stained cellular structures that are extremely vulnerable to damage (the oldest specimens were more than 160 years old). -

Buzzle – Zoology Terms – Glossary of Biology Terms and Definitions Http

Buzzle – Zoology Terms – Glossary of Biology Terms and Definitions http://www.buzzle.com/articles/biology-terms-glossary-of-biology-terms-and- definitions.html#ZoologyGlossary Biology is the branch of science concerned with the study of life: structure, growth, functioning and evolution of living things. This discipline of science comprises three sub-disciplines that are botany (study of plants), Zoology (study of animals) and Microbiology (study of microorganisms). This vast subject of science involves the usage of myriads of biology terms, which are essential to be comprehended correctly. People involved in the science field encounter innumerable jargons during their study, research or work. Moreover, since science is a part of everybody's life, it is something that is important to all individuals. A Abdomen: Abdomen in mammals is the portion of the body which is located below the rib cage, and in arthropods below the thorax. It is the cavity that contains stomach, intestines, etc. Abscission: Abscission is a process of shedding or separating part of an organism from the rest of it. Common examples are that of, plant parts like leaves, fruits, flowers and bark being separated from the plant. Accidental: Accidental refers to the occurrences or existence of all those species that would not be found in a particular region under normal circumstances. Acclimation: Acclimation refers to the morphological and/or physiological changes experienced by various organisms to adapt or accustom themselves to a new climate or environment. Active Transport: The movement of cellular substances like ions or molecules by traveling across the membrane, towards a higher level of concentration while consuming energy. -

METABOLIC EVOLUTION in GALDIERIA SULPHURARIA By

METABOLIC EVOLUTION IN GALDIERIA SULPHURARIA By CHAD M. TERNES Bachelor of Science in Botany Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 2009 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May, 2015 METABOLIC EVOLUTION IN GALDIERIA SUPHURARIA Dissertation Approved: Dr. Gerald Schoenknecht Dissertation Adviser Dr. David Meinke Dr. Andrew Doust Dr. Patricia Canaan ii Name: CHAD M. TERNES Date of Degree: MAY, 2015 Title of Study: METABOLIC EVOLUTION IN GALDIERIA SULPHURARIA Major Field: PLANT SCIENCE Abstract: The thermoacidophilic, unicellular, red alga Galdieria sulphuraria possesses characteristics, including salt and heavy metal tolerance, unsurpassed by any other alga. Like most plastid bearing eukaryotes, G. sulphuraria can grow photoautotrophically. Additionally, it can also grow solely as a heterotroph, which results in the cessation of photosynthetic pigment biosynthesis. The ability to grow heterotrophically is likely correlated with G. sulphuraria ’s broad capacity for carbon metabolism, which rivals that of fungi. Annotation of the metabolic pathways encoded by the genome of G. sulphuraria revealed several pathways that are uncharacteristic for plants and algae, even red algae. Phylogenetic analyses of the enzymes underlying the metabolic pathways suggest multiple instances of horizontal gene transfer, in addition to endosymbiotic gene transfer and conservation through ancestry. Although some metabolic pathways as a whole appear to be retained through ancestry, genes encoding individual enzymes within a pathway were substituted by genes that were acquired horizontally from other domains of life. Thus, metabolic pathways in G. sulphuraria appear to be composed of a ‘metabolic patchwork’, underscored by a mosaic of genes resulting from multiple evolutionary processes. -

Seaweed Products on the Swedish Market As a Source of Omega-3 Fatty Acids

Faculty of Natural Resources and Agricultural Sciences Department of Food Science Seaweed products on the Swedish market as a source of omega-3 fatty acids Sjögräsprodukter på den svenska marknaden som en källa till omega-3 fettsyror Helena Martinsson Independent Project in Food Science• Master Thesis • 30 hec • Advanced A2E Publikation/Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet, Institutionen för livsmedelsvetenskap, no 430 Uppsala, 2016 Seaweed products on the Swedish market as a source of omega-3 fatty acids Sjögräsprodukter på den svenska marknaden som en källa till omega-3 fettsyror Helena Martinsson Supervisor: Jana Pickova, Department of food science Examiner: Kristine Koch, Department of food science Credits: 30 hec Level: Advanced A2E Course title: Independent Project in Food Science – Master Thesis Course code: EX0425 Programme/education: Agronomy in Food Science Place of publication: Uppsala Year of publication: 2016 Title of series: Publikation/Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet, Institutionen för livsmedelsvetenskap Serie no: 430 Online publication: http://stud.epsilon.slu.se Keywords: macroalgae, rhodophyta, phaeophyta, ω-3 fatty acids, polyunsaturated fatty acds Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Faculty of Natural Resources and Agricultural Sciences Department of Food Science Abstract To know if seaweed products on the Swedish markets could contribute to a better ω3 polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) nutritional status a selection of eight dried red and brown macroalgae were chosen for this study. The fat content was deter- mined in all the algae and the fatty acid composition was examined by gas chroma- tography. Overall the seaweeds displayed a low fat content with 0.24 and 3.28g/100g dry weight (DW). The red algae Porphyra yezoensis had the highest content of PUFAs with 58.7% and also the highest content of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) with 49.8%, while Undaria pinnatifida displayed the second highest levels with 44.4% PUFA and 13.3% EPA. -

Differentiation Between Some Ulva Spp. by Morphological, Genetic and Biochemical Analyses

Филогенетика Вавиловский журнал генетики и селекции. 2017;21(3):360367 ОРИГИНАЛЬНОЕ ИССЛЕДОВАНИЕ / ORIGINAL ARTICLE DOI 10.18699/VJ17.253 Differentiation between some Ulva spp. by morphological, genetic and biochemical analyses M.M. Ismail1 , S.E. Mohamed2 1 Marine Environmental Division, National Institute of Oceanography and Fisheries, Alexandria, Egypt 2 Department of Molecular Biology, Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology Research Institute, Sadat City University, Sadat City, Egypt Ulva is most common green seaweed in Egypt coast, it used as a Различия между некоторыми source of food, feed, medicines and fertilizers in all the world. This study is the first time to investigate the morphological, genetic видами рода Ulva, выявленные and biochemical variation within four Ulva species collected путем морфологического, from Eastern Harbor, Alexandria. The morphology description of генетического и биохимического thallus showed highly variations according to species, but there is not enough data to make differentiation between species in the анализа same genus since it is impacted with environmental factors and development stage of seaweeds. Genetic variations between the М.М. Исмаил1 , С.Э. Мохамед2 tested Ulva spp. were analyzed using random amplified polymor phic DNA (RAPD) analyses which shows that it would be possible 1 Отдел исследований морской среды Национального института to establish a unique fingerprint for individual seaweeds based on океанографии и рыболовства, Александрия, Египет 2 Отдел молекулярной биологии Исследовательского института the combined results generated from a small collection of prim генной инженерии и биотехнологий, Садатский университет, ers. The dendrogram showed that the most closely species are Садат, Египет U. lactuca and U. compressa, while, U. fasciata was far from both U. -

Kappaphycus Alvarezii) in Malaysian Food Products

International Food Research Journal 26(6): 1677-1687 (December 2019) Journal homepage: http://www.ifrj.upm.edu.my Application of seaweed (Kappaphycus alvarezii) in Malaysian food products Mohammad, S. M., Mohd Razali, S. F., Mohamad Rozaiman, N. H. N., Laizani, A. N. and *Zawawi, N. Faculty of Food Science and Technology, Universiti Putra Malaysia, 43400 UPM Serdang, Malaysia Article history Abstract Received: 15 August, 2018 Kappaphycus alvarezii is a species of red algae, and one of the most important carrageenan Received in revised form: sources for food, cosmetic, and pharmaceutical industries. It is commercially cultivated in the 24 May, 2019 eastern part of Malaysia. Although K. alvarezii is rich in nutrients, it is limited in its integration Accepted: 25 September, 2019 into Malaysian food products. Therefore, the present work was conducted to investigate the quality characteristics, sensorial attributes, and antioxidant activity of K. alvarezii in Malaysian food products. Seaweed puree (SP) from K. alvarezii at 10%, 20% and 30% concentrations were Keywords prepared in the formulations of fish sausages, flat rice noodles and yellow alkaline noodles. Seaweed, Kappaphycus Proximate analysis, physicochemical analysis, microbial count, total phenolic content (TPC), Alvarezii, Fish sausages, sensory evaluation, and consumer acceptance survey of the formulated food were conducted. Noodle, Physicochemical The incorporation of K. alvarezii significantly increased the fibre, moisture, and ash content in properties, Consumer formulated foods. In addition, the TPC content of K. alvarezii food also significantly increased acceptance up to 42 mg GAE/100 g. The presence of SP in food at higher concentration decreased the microbial counts. Sensory analysis confirmed that only fish sausages added with SP was overall acceptable as compared to control. -

Kelp Cultivation Effectively Improves Water Quality and Regulates Phytoplankton Community in a Turbid, Highly Eutrophic Bay

Science of the Total Environment 707 (2020) 135561 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Science of the Total Environment journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/scitotenv Kelp cultivation effectively improves water quality and regulates phytoplankton community in a turbid, highly eutrophic bay Zhibing Jiang a,b,d, Jingjing Liu a,ShangluLic,YueChena,PingDua,b,YuanliZhua,YiboLiaoa,d, Quanzhen Chen a, Lu Shou a, Xiaojun Yan e, Jiangning Zeng a,⁎, Jianfang Chen a,d a Key Laboratory of Marine Ecosystem and Biogeochemistry, State Oceanic Administration & Second Institute of Oceanography, Ministry of Natural Resources, Hangzhou, China b Function Laboratory for Marine Fisheries Science and Food Production Processes, Pilot National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology (Qingdao), Qingdao, China c Marine Monitoring and Forecasting Center of Zhejiang Province, Hangzhou, China d State Key Laboratory of Satellite Ocean Environment Dynamics, Second Institute of Oceanography, Ministry of Natural Resources, Hangzhou, China e Key Laboratory of Applied Marine Biotechnology, Ministry of Education, Marine College of Ningbo University, Ningbo, China HIGHLIGHTS GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT • Kelp farming alleviated eutrophication and acidification. • Kelp farming greatly relieved light limi- tation and increased phytoplankton bio- mass. • Kelp farming appreciably enhanced phytoplankton diversity. • Kelp farming reduced the dominance of dinoflagellate Prorocentrum minimum. • Phytoplankton community differed sig- nificantly between the kelp farm and control area. article info abstract Article history: Coastal eutrophication and its associated harmful algal blooms have emerged as one of the most severe environ- Received 19 September 2019 mental problems worldwide. Seaweed cultivation has been widely encouraged to control eutrophication and Received in revised form 11 November 2019 algal blooms. Among them, cultivated kelp (Saccharina japonica) dominates primarily by production and area. -

THE CASE AGAINST Marine Mammals in Captivity Authors: Naomi A

s l a m m a y t T i M S N v I i A e G t A n i p E S r a A C a C E H n T M i THE CASE AGAINST Marine Mammals in Captivity The Humane Society of the United State s/ World Society for the Protection of Animals 2009 1 1 1 2 0 A M , n o t s o g B r o . 1 a 0 s 2 u - e a t i p s u S w , t e e r t S h t u o S 9 8 THE CASE AGAINST Marine Mammals in Captivity Authors: Naomi A. Rose, E.C.M. Parsons, and Richard Farinato, 4th edition Editors: Naomi A. Rose and Debra Firmani, 4th edition ©2009 The Humane Society of the United States and the World Society for the Protection of Animals. All rights reserved. ©2008 The HSUS. All rights reserved. Printed on recycled paper, acid free and elemental chlorine free, with soy-based ink. Cover: ©iStockphoto.com/Ying Ying Wong Overview n the debate over marine mammals in captivity, the of the natural environment. The truth is that marine mammals have evolved physically and behaviorally to survive these rigors. public display industry maintains that marine mammal For example, nearly every kind of marine mammal, from sea lion Iexhibits serve a valuable conservation function, people to dolphin, travels large distances daily in a search for food. In learn important information from seeing live animals, and captivity, natural feeding and foraging patterns are completely lost. -

The Polyp and the Medusa Life on the Move

The Polyp and the Medusa Life on the Move Millions of years ago, unlikely pioneers sparked a revolution. Cnidarians set animal life in motion. So much of what we take for granted today began with Cnidarians. FROM SHAPE OF LIFE The Polyp and the Medusa Life on the Move Take a moment to follow these instructions: Raise your right hand in front of your eyes. Make a fist. Make the peace sign with your first and second fingers. Make a fist again. Open your hand. Read the next paragraph. What you just did was exhibit a trait we associate with all animals, a trait called, quite simply, movement. And not only did you just move your hand, but you moved it after passing the idea of movement through your brain and nerve cells to command the muscles in your hand to obey. To do this, your body needs muscles to move and nerves to transmit and coordinate movement, whether voluntary or involuntary. The bit of business involved in making fists and peace signs is pretty complex behavior, but it pales by comparison with the suites of thought and movement associated with throwing a curve ball, walking, swimming, dancing, breathing, landing an airplane, running down prey, or fleeing a predator. But whether by thought or instinct, you and all animals except sponges have the ability to move and to carry out complex sequences of movement called behavior. In fact, movement is such a basic part of being an animal that we tend to define animalness as having the ability to move and behave. -

Neoproterozoic Origin and Multiple Transitions to Macroscopic Growth in Green Seaweeds

Neoproterozoic origin and multiple transitions to macroscopic growth in green seaweeds Andrea Del Cortonaa,b,c,d,1, Christopher J. Jacksone, François Bucchinib,c, Michiel Van Belb,c, Sofie D’hondta, f g h i,j,k e Pavel Skaloud , Charles F. Delwiche , Andrew H. Knoll , John A. Raven , Heroen Verbruggen , Klaas Vandepoeleb,c,d,1,2, Olivier De Clercka,1,2, and Frederik Leliaerta,l,1,2 aDepartment of Biology, Phycology Research Group, Ghent University, 9000 Ghent, Belgium; bDepartment of Plant Biotechnology and Bioinformatics, Ghent University, 9052 Zwijnaarde, Belgium; cVlaams Instituut voor Biotechnologie Center for Plant Systems Biology, 9052 Zwijnaarde, Belgium; dBioinformatics Institute Ghent, Ghent University, 9052 Zwijnaarde, Belgium; eSchool of Biosciences, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC 3010, Australia; fDepartment of Botany, Faculty of Science, Charles University, CZ-12800 Prague 2, Czech Republic; gDepartment of Cell Biology and Molecular Genetics, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742; hDepartment of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138; iDivision of Plant Sciences, University of Dundee at the James Hutton Institute, Dundee DD2 5DA, United Kingdom; jSchool of Biological Sciences, University of Western Australia, WA 6009, Australia; kClimate Change Cluster, University of Technology, Ultimo, NSW 2006, Australia; and lMeise Botanic Garden, 1860 Meise, Belgium Edited by Pamela S. Soltis, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, and approved December 13, 2019 (received for review June 11, 2019) The Neoproterozoic Era records the transition from a largely clear interpretation of how many times and when green seaweeds bacterial to a predominantly eukaryotic phototrophic world, creat- emerged from unicellular ancestors (8). ing the foundation for the complex benthic ecosystems that have There is general consensus that an early split in the evolution sustained Metazoa from the Ediacaran Period onward. -

Successions of Phytobenthos Species in a Mediterranean Transitional Water System: the Importance of Long Term Observations

A peer-reviewed open-access journal Nature ConservationSuccessions 34: 217–246 of phytobenthos (2019) species in a Mediterranean transitional water system... 217 doi: 10.3897/natureconservation.34.30055 RESEARCH ARTICLE http://natureconservation.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity conservation Successions of phytobenthos species in a Mediterranean transitional water system: the importance of long term observations Antonella Petrocelli1, Ester Cecere1, Fernando Rubino1 1 Water Research Institute (IRSA) – CNR, via Roma 3, 74123 Taranto, Italy Corresponding author: Antonella Petrocelli ([email protected]) Academic editor: A. Lugliè | Received 25 September 2018 | Accepted 28 February 2019 | Published 3 May 2019 http://zoobank.org/5D4206FB-8C06-49C8-9549-F08497EAA296 Citation: Petrocelli A, Cecere E, Rubino F (2019) Successions of phytobenthos species in a Mediterranean transitional water system: the importance of long term observations. In: Mazzocchi MG, Capotondi L, Freppaz M, Lugliè A, Campanaro A (Eds) Italian Long-Term Ecological Research for understanding ecosystem diversity and functioning. Case studies from aquatic, terrestrial and transitional domains. Nature Conservation 34: 217–246. https://doi.org/10.3897/ natureconservation.34.30055 Abstract The availability of quantitative long term datasets on the phytobenthic assemblages of the Mar Piccolo of Taranto (southern Italy, Mediterranean Sea), a lagoon like semi-enclosed coastal basin included in the Italian LTER network, enabled careful analysis of changes occurring in the structure of the community over about thirty years. The total number of taxa differed over the years. Thirteen non-indigenous species in total were found, their number varied over the years, reaching its highest value in 2017. The dominant taxa differed over the years.