Christina Belter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keybank Broadway at the Paramount and Seattle Theatre Group Announce the 2013/2014 Season Of

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE FEBRUARY 18, 2013 Media Contacts: Julie Furlong, Furlong Communications, Inc., 206.850.9448, [email protected] Antonio Hicks, Seattle Theatre Group, 206.315.8016, [email protected] KeyBank Broadway at The Paramount and Seattle Theatre Group Announce The 2013/2014 Season of SEATTLE – The 2013/2014 KeyBank Broadway at The Paramount Season will bring another year of unforgettable entertainment to The Paramount Theatre, with a roster of Broadway blockbusters and some venerable favorites. The 2013/2014 Season starts with the magical and enchanting THE WIZARD OF OZ, followed by PRISCILLA QUEEN OF THE DESERT, the joyously fun show featuring a trio of friends on a journey in search of love and friendship. The season continues with all time favorites EVITA and Disney’s THE LION KING and finally culminates with eight time Tony Award® winner, ONCE, about a Dublin street musician who’s about to give up his dream when a beautiful young woman takes a sudden interest in his haunting love songs. For more information, please visit, www.stgpresents.org/Broadway. The line up for the 2013/2014 KeyBank Broadway at The Paramount Season is as follows: THE WIZARD OF OZ October 9-13, 2013 PRISCILLA QUEEN OF THE DESERT November 12-17, 2013 EVITA December 31, 2013-January 5, 2014 Disney’s THE LION KING March 11-April 6, 2014 ONCE May 27-June 8, 2014 The 2013/2014 Season THE WIZARD OF OZ October 9-13, 2013 “We’re off to see….” The most magical adventure of them all. Andrew Lloyd Webber’s new production of The Wizard of Oz is an enchanting adaptation of the all-time classic, totally reconceived for the stage by the award-winning creative team that recently delighted London and Toronto audiences with the revival of The Sound of Music. -

Proposed Cultural Awareness Schedule for 2000

CULTURAL ARTS SERIES 2008– 2009 (Schedule) A Classical Celebration! Oklahoma City Community College Artist Performance Date Lark Chamber Artists – Strings, Piano, Woodwinds, and Percussion Tues. Sept. 16, 7:00 P.M. The Romeros – Guitar Quartet (Special venue; Westminster Presbyterian Church) Tues. Oct. 7, 7:00 P.M. Jerusalem Lyric Trio – Soprano, Flute, and Piano Tues. Nov. 18, 7:00 P.M. The Four Freshmen – Vocal Quartet Tues. Dec. 2, 7:00 P.M. The Texas Gypsies – Gypsy/Texas Swing Jazz Quintet Tues. Feb. 17, 7:00 P.M. Rosario Andino – Pianist Tues. Mar. 3, 7:00 P.M. Best of Broadway – Vocal Trio Tues. Apr. 14, 7:00 P.M. Brad Richter, Viktor Uzur – Guitar and Cello Thurs. May 7, 7:00 p.m. • Lark Chamber Artists – Strings, Piano, Woodwinds, and Percussion Ensemble Lecture – TBA Performance – Tuesday, September 16, 2008, 7:00 p.m., Oklahoma City Community College Theatre. A diverse selection of musical delights. (Short) Lark Chamber Artists present a broad range of musical styles, embracing the traditional as well as adventuresome commissions and collaborations. (Medium) Lark Chamber Artists is a uniquely structured ensemble who present a broad range of musical styles, embracing the traditional favorites of the chamber music repertoire, as well as adventuresome commissions and collaborations for a new standard in innovative programming. (Long) As an outgrowth of the world-renowned Lark Quartet, Lark Chamber Artists (LCA) is a uniquely structured ensemble featuring some of today's most active performers who have come together to present a broad range of musical styles, embracing the traditional favorites of the chamber music repertoire, as well as adventuresome commissions and collaborations for a new standard in innovative programming. -

The Bible in Music

The Bible in Music 115_320-Long.indb5_320-Long.indb i 88/3/15/3/15 66:40:40 AAMM 115_320-Long.indb5_320-Long.indb iiii 88/3/15/3/15 66:40:40 AAMM The Bible in Music A Dictionary of Songs, Works, and More Siobhán Dowling Long John F. A. Sawyer ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • London 115_320-Long.indb5_320-Long.indb iiiiii 88/3/15/3/15 66:40:40 AAMM Published by Rowman & Littlefield A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowman.com Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB Copyright © 2015 by Siobhán Dowling Long and John F. A. Sawyer All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dowling Long, Siobhán. The Bible in music : a dictionary of songs, works, and more / Siobhán Dowling Long, John F. A. Sawyer. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8108-8451-9 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8108-8452-6 (ebook) 1. Bible in music—Dictionaries. 2. Bible—Songs and music–Dictionaries. I. Sawyer, John F. A. II. Title. ML102.C5L66 2015 781.5'9–dc23 2015012867 ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. -

Thebestarts.Com Presents “The Lion Sings Tonight” a Cabaret

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Kevin Ireland, theBestArts.com – Atlanta benefit presenter http://www.thebestarts.com/lionkingbenefitpresskit/ 678-638-4301 email: [email protected] Jerry Henderson, Joining Hearts – Marketing Manager 404-216-8794 email: [email protected] Jennifer Walker, Broadway in Atlanta – BRAVE Public Relations 404-233-3993 e-mail: [email protected] theBestArts.com presents “The Lion Sings Tonight” A cabaret featuring cast members from DISNEY’S THE LION KING Monday, April 21, 2014, at 7:30pm Rich Theatre – Woodruff Arts Center – 1280 Peachtree Street, Atlanta to benefit Joining Hearts and Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS On Monday, April 21st at 7:30pm, theBestArts.com will present its fifth Broadway benefit cabaret in Atlanta, THE LION SINGS TONIGHT. The evening will feature performances by cast and crew members of the Broadway national touring company of DISNEY’S THE LION KING at the Woodruff Arts Center’s Rich Theatre in midtown Atlanta. 100% of ticket revenue from this event will go directly to JOINING HEARTS and BROADWAY CARES/EQUITY FIGHTS AIDS (BC/EFA). Produced by Kevin Ireland, founder of theBestArts.com, along with DISNEY’S THE LION KING company members Ben Lipitz and Jelani Remy, the evening will have audience members Dancing In Their Seats to top 60s hits from Aretha Franklin, the Supremes, Marvin Gaye, the Temptations, the Rolling Stones, Gladys Knight and many more. Over 25 singers, dancers and musicians from the company will showcase their diverse singing and dance talents, accompanied by a live band. A mid-show auction will present opportunities to join the company backstage at THE FOX THEATRE and a June trip to NYC to attend the Broadway show of your choice AND Broadway Bares. -

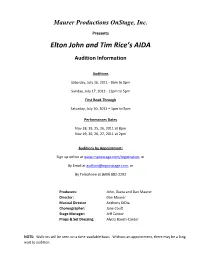

Elton John and Tim Rice's AIDA

Maurer Productions OnStage, Inc. Presents Elton John and Tim Rice’s AIDA Audition Information Auditions Saturday, July 16, 2011 - 9am to 5pm Sunday, July 17, 2011 - 12pm to 5pm First Read-Through Saturday, July 30, 2011 – 1pm to 5pm Performances Dates Nov 18, 19, 25, 26, 2011 at 8pm Nov 19, 20, 26, 27, 2011 at 2pm Auditions by Appointment: Sign up online at www.mponstage.com/registration, or By Email at [email protected], or By Telephone at (609) 882-2292 Producers: John, Diana and Dan Maurer Director: Dan Maurer Musical Director Anthony DiDia Choreographer: Jane Coult Stage Manager: Jeff Cantor Props & Set Dressing: Alycia Bauch-Cantor NOTE: Walk-ins will be seen on a time-available basis. Without an appointment, there may be a long wait to audition. Auditions for Elton John & Tim Rice’s AIDA Index 1. About the Show 2. Available Roles 3. What You Need to Know About the Audition 4. Audition Application 5. Calendar for Conflicts 6. Musical Numbers 7. Audition Monologues 1 Elton John and Tim Rice’s Aida Directed by Dan Maurer Part Broadway musical, part dance spectacular and part rock concert, AIDA is an epic tale about the power and timelessness of love. The show features over twenty roles for singers, dancers, and actors of various races and will be staged by the award winning production team that brought shows like Man of La Mancha and Singin’ in the Rain to Kelsey Theatre. Winner of four Tony Awards when Disney’s Hyperion Theatrical Group first brought it to Broadway, AIDA features music by pop legend Elton John and lyrics by Tim Rice, who wrote the lyrics for hit shows like Jesus Christ Superstar and Evita. -

Hw Biography 2021

HUGH WOOLDRIDGE Director and Lighting Designer; Visiting Professor Hugh Wooldridge has produced, directed and devised theatre and television productions all over the world. He has taught and given master-classes in the UK, Europe, the US, South Africa and Australia. He trained at the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art (LAMDA) and made his West End debut as an actor in The Dame of Sark with Dame Celia Johnson. Subsequently he performed with the London Festival Ballet / English National Ballet in the world premiere production of Romeo and Juliet choreographed by Rudolph Nureyev. At the age of 22, he directed The World of Giselle for Dame Ninette de Valois and the Royal Ballet. Since this time, he has designed lighting for new choreography with dance companies around the world including The Royal Ballet, Dance Theatre London, Rambert Dance Company, the National Youth Ballet and the English National Ballet Company. He directed the world premieres of the Graham Collier / Malcolm Lowry Jazz Suite Under A Volcano and The Undisput’d Monarch of the English Stage with Gary Bond portraying David Garrick; the Charles Strouse opera, Nightingale with Sarah Brightman at the Buxton Opera Festival; Francis Wyndham’s Abel and Cain (Haymarket, Leicester) with Peter Eyre and Sean Baker. He directed and lit the original award-winning Jeeves Takes Charge at the Lyric Hammersmith; the first productions of the Andrew Lloyd Webber and T. S. Eliot Cats (Sydmonton Festival), and the Andrew Lloyd Webber / Don Black song-cycle Tell Me 0n a Sunday with Marti Webb at the Royalty (now Peacock) Theatre; also Lloyd Webber’s Variations at the Royal Festival Hall (later combined together to become Song and Dance) and Liz Robertson’s one-woman show Just Liz compiled by Alan Jay Lerner at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London. -

American Music Research Center Journal

AMERICAN MUSIC RESEARCH CENTER JOURNAL Volume 19 2010 Paul Laird, Guest Co-editor Graham Wood, Guest Co-editor Thomas L. Riis, Editor-in-Chief American Music Research Center College of Music University of Colorado Boulder THE AMERICAN MUSIC RESEARCH CENTER Thomas L. Riis, Director Laurie J. Sampsel, Curator Eric J. Harbeson, Archivist Sister Mary Dominic Ray, O.P. (1913–1994), Founder Karl Kroeger, Archivist Emeritus William Kearns, Senior Fellow Daniel Sher, Dean, College of Music William S. Farley, Research Assistant, 2009–2010 K. Dawn Grapes, Research Assistant, 2009–2011 EDITORIAL BOARD C. F. Alan Cass Kip Lornell Susan Cook Portia Maultsby Robert R. Fink Tom C. Owens William Kearns Katherine Preston Karl Kroeger Jessica Sternfeld Paul Laird Joanne Swenson-Eldridge Victoria Lindsay Levine Graham Wood The American Music Research Center Journal is published annually. Subscription rate is $25.00 per issue ($28.00 outside the U.S. and Canada). Please address all inquiries to Lisa Bailey, American Music Research Center, 288 UCB, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309-0288. E-mail: [email protected] The American Music Research Center website address is www.amrccolorado.org ISSN 1058-3572 © 2010 by the Board of Regents of the University of Colorado INFORMATION FOR AUTHORS The American Music Research Center Journal is dedicated to publishing articles of general interest about American music, particularly in subject areas relevant to its collections. We welcome submission of articles and pro- posals from the scholarly community, ranging from 3,000 to 10,000 words (excluding notes). All articles should be addressed to Thomas L. Riis, College of Music, University of Colorado Boulder, 301 UCB, Boulder, CO 80309-0301. -

The Celluloid Christ: Godspell Church of the Saviour Lenten Study - 2011 (Leader: Lejf E

9 VIEWING GUIDE: Godspell (1973 D. Greene) The Celluloid Christ: Godspell Church of the Saviour Lenten Study - 2011 (leader: Lejf E. Knutson) 9 “The characters in Godspell can be looked at in two ways, and both are inspired. On one hand, these people could literally be Jesus, John, and the disciples, in a story updated to modern day New York. With this approach, their colorful outfits, face-painting, and childish antics truly puts into perspective how bizarre and radical Jesus’ actions must have been in first century Israel, and yet these people are filled with so much joy and happiness that, much like in The Apostle, we find their lifestyle contagious. On the other hand, I choose to view this film not as a literal update of Christ’s life, but as a group of radicals living in New York embracing the teachings of Christ as a lifestyle. As a result, they are simply playing the life of Christ out to get a better understanding of his ideas. Either way, the message is the same: Be yourself, be radical, push the envelope, and love one another. Godspell is a film breathing with life and joy.”1 “In anything remotely resembling something that could begin to be called a religious sense, Godspell is a zero; it’s Age-of Aquarius Love fed through a quasi-gospel funnel, with a few light-hearted supernatural touches. ”2 “Turn On, Tune In, Drop Out – Find God” – David Greene’s Godspell (1973) I concluded my discussion of The Gospel According to St. Matthew with a deliberately (or hopefully) provocative statement: “What would a Jesus film look like if it tried to present Jesus preaching his revolutionary, world-upsetting ethos of the kingdom in the here and now, in the heart of the modern city?” – and then suggested that Godspell would be an answer to that question. -

June 1-3,2(>(>7

Leonard A. Anderson M. Seth Reines Executive Director Artistic Director June 1-3,2(>(>7 nte Media -I1 I - I , ,, This program is partially supportec grant from the Illinois Arts Council. Named a Partner In Excellence by the Illinois Arts Council. IF IT'S GOT OUR NAME ON IT YOlU'VE GOT OUR WORD ON If. attachments that are tough enough for folks Ib you. And then we put wr gllarantee on m,m, In fact,we ofb the WustryS only 3-year warm&, Visit mgrHd.com. Book By James Goldman Music Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim Produced Originally on Broadway by Harold Prince By special arrangement with Cameron Mackintosh Directed & Staged by Tony Parise Assistant To The Directorr AEA Stage Manager Marie Jagger-Taylor* Tom Reynolds* Lighting Designer Musical Director Sound Designer Joe Spratt P. Jason Yarcho David J. Scobbie The Cast (In Order of Appearance) Dimitri Weismann .............................................................................................Guy S. Little Jr.* Roscoe....................................................................................................................... Tom Bunfill Phyllis Rogers Stone................................................................................... Colleen Zenk Pinter* Benjamin Stone....................................................................................................... Mark Pinter* Sally Durant Plumrner........................................................................................ a McNeely* Buddy Plummer........................................................................................................ -

Spotlight on Learning Oliver

Spotlight on Learning a Pioneer Theatre Company Classroom Companion Pioneer Theatre Company’s Student Matinee Program is made possible through the support of Salt Lake Oliver County’s Zoo, Arts and Music, Lyrics and Book by Lionel Bart Parks Program, Salt Dec. 2 - 17, 2016 Lake City Arts Council/ Directed by Karen Azenberg Arts Learning Program, The Simmons “Bleak, dark, and piercing cold, it was a night for the well-housed and Family Foundation, The fed to draw round the bright fire, and thank God they were at home; Meldrum Foundation and for the homeless starving wretch to lay him down and die. Many Endowment Fund and hunger-worn outcasts close their eyes in our bare streets at such times, R. Harold Burton who, let their crimes have been what they may, can hardly open them in Foundation. a more bitter world.” “Please sir, I want some more.” – Charles Dickens, Oliver Twist (1837) All these years after Charles Dickens wrote these words, there are still Spotlight on Learning is provided families without homes and children who are hungry. to students through a grant As this holiday season approaches, I am grateful for health, home, and family provided by the — but am also reminded by Oliver! to take a moment to remember those less George Q. Morris Foundation fortunate. I thank you for your support of Pioneer Theatre Company and wish you the merriest of holidays, and a happy and healthy New Year. Karen Azenberg Approx. running time: Artistic Director 2 hours and 15 minutes, including one fifteen-minute intermission. Note for Teachers: “Food, Glorious Food!” Student Talk-Back: Help win the fight against hunger by encouraging your students to bring There will be a Student Talk-Back a food donation (canned or boxed only) to your performance of Oliver! directly after the performance. -

Alistair Brammer Photo: MUG Photography

Paddock Suite, The Courtyard, 55 Charterhouse Street, London, EC1M 6HA p: + 44 (0) 20 73360351 e: [email protected] Alistair Brammer Photo: MUG Photography Location: London Other: Equity Height: 5'11" (180cm) Eye Colour: Blue Weight: 11st. 7lb. (73kg) Hair Colour: Sandy Playing Age: 22 - 34 years Hair Length: Short Musical 2017, Musical, Chris, Miss Saigon, Broadway Theatre, New York, Cameron Mackintosh, Laurence Connor 2016, Musical, Enjolras, Les Miserables, Dubai Opera House, Cameron Mackintosh 2014, Musical, Chris, Miss Saigon, Cameron Mackintosh, Laurence Connor 2012, Musical, Billy, Taboo, Danielle Tarento, Christopher Renshaw 2011, Musical, Walter/ 1st Cover Claude, Hair, European Arena Tour, Arena Show Entertainment, Stanislav Mosa 2010, Musical, Jean Prouvaire, Les Miserables 25th Anniversary Concert, 02 Arena, Laurence Connor, James Powell 2009, Musical, Marius, Les Miserables 2009 - 2011, Queens Theatre, Trevor Nunn 2008, Musical, Alternate Joseph/Zebulun/Benjamin, Joseph And The Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat 2008-2009, National Tour, Bill Kenwright Stage 2013, Stage, Billy, War Horse, National Theatre, Marianne Elliott & Tom Morris Television 2018, Television, Adam, Someone You Thought You Knew, October Films / Discovery, Stuart Wilson 2016, Television, Oliver, Vicious, Brown Eyed Boy / ITV 2015, Television, Jack Diamond, Casualty, BBC, Various 2014, Television, Eric, Episodes, Hat Trick / BBC, Iain Macdonald Film 2018, Feature Film, Head Full Of Honey, Warner Brothers, Til Schweiger 2018, Feature Film, Leo Marks, Miss Atkins -

OLIVER! Education Pack

INTRODUCTION 3 Welcome to the OLIVER! Education Pack WHAT THE DICKENS? 4 An introduction to the world of Charles Dickens IMAGINATION 5 Using OLIVER! To spark students ideas GRAPHIC DESIGN 6 A photocopiable worksheet using the OLIVER! logo as inspiration. UNDERTAKING 7 Using Sowerberry and his funeral parlour as inspiration for classroom activities CRITICAL ISSUES 8 Considering staging as well as themes with a modern day parallel OLIVER THE SOAP OPERA! 9 A photocopiable worksheet for students to create their own Soap Opera based on OLIVER! WALK THE WALK 10 Using movement and „Characters on trial‟! TALK THE TALK 11 Ask an Agony Aunt, or create a dictionary in text speak MARKETING THE SHOW 12 A photocopiable worksheet for students to create their own marketing for OLIVER! CREATE REALITY 13 Big Brother and a costume-making task RESOURCES 14 Links and Resources to help you to further explore OLIVER! Photographs in this Education Pack are taken from the UK tour and West End productions 2 Cameron Mackintosh, "the most successful, influential and powerful theatrical producer in the world" (The New York Times), first saw OLIVER! in its inaugural West End production at the New Theatre (now the Noel Coward), starring Ron Moody as Fagin and Barry Humphries in the small comic role of Mr Sowerberry. He sat with his Aunt in the Gallery and paid 1s 6d. The production that graces the stage today demonstrates Cameron Mackintosh‟s passion for Lionel Bart‟s musical about a young orphan boy and his adventures in Victorian London. The lavish show features a cast and orchestra of more than 100.