Roswell, TEXTUAL GAPS and FANS' SUBVERSIVE RESPONSE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The BG News September 15, 2016

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 9-15-2016 The BG News September 15, 2016 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation State University, Bowling Green, "The BG News September 15, 2016" (2016). BG News (Student Newspaper). 8931. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/8931 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. An independent student press serving the campus and surrounding community, ESTABLISHED 1920 Bowling Green State University Thursday, September 15, 2016 | Volume 96, Issue 9 HOME FIELD The Falcon football team will return to the Doyt for Family Weekend to face Middle Tennessee. | PAGE 8 Predictions Native New health for the 68th American team insurance raises Primetime names are still concerns for Emmy Awards problematic students PAGE 11 PAGE 5 PAGE 7 AY ZIGGY! 2016 FALCON FOOTBALL GET YOUR ORANGE ON BGSU VS. MIDDLE TENNESSEE SATURDAY, SEPT. 17, NOON | FAMILY WEEKEND BGSUFALCONS.COM/STUDENT TICKETS BG NEWS September 15, 2016 | PAGE 12 Solar project to power 3,000 households By Kevin Bean Green’s energy portfolio. As the portfolio “The panels in our solar farm will provide energy to the city in an efficient Reporter stands now, approximately 36 percent of actually move as the sun moves across manner. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

The Walking Dead,” Which Starts Its Final We Are Covid-19 Safe-Practice Compliant Season Sunday on AMC

Las Cruces Transportation August 20 - 26, 2021 YOUR RIDE. YOUR WAY. Las Cruces Shuttle – Taxi Charter – Courier Veteran Owned and Operated Since 1985. Jeffrey Dean Morgan Call us to make is among the stars of a reservation today! “The Walking Dead,” which starts its final We are Covid-19 Safe-Practice Compliant season Sunday on AMC. Call us at 800-288-1784 or for more details 2 x 5.5” ad visit www.lascrucesshuttle.com PHARMACY Providing local, full-service pharmacy needs for all types of facilities. • Assisted Living • Hospice • Long-term care • DD Waiver • Skilled Nursing and more Life for ‘The Walking Dead’ is Call us today! 575-288-1412 Ask your provider if they utilize the many benefits of XR Innovations, such as: Blister or multi-dose packaging, OTC’s & FREE Delivery. almost up as Season 11 starts Learn more about what we do at www.rxinnovationslc.net2 x 4” ad 2 Your Bulletin TV & Entertainment pullout section August 20 - 26, 2021 What’s Available NOW On “Movie: We Broke Up” “Movie: The Virtuoso” “Movie: Vacation Friends” “Movie: Four Good Days” From director Jeff Rosenberg (“Hacks,” Anson Mount (“Hell on Wheels”) heads a From director Clay Tarver (“Silicon Glenn Close reunited with her “Albert “Relative Obscurity”) comes this 2021 talented cast in this 2021 actioner that casts Valley”) comes this comedy movie about Nobbs” director Rodrigo Garcia for this comedy about Lori and Doug (Aya Cash, him as a professional assassin who grapples a straight-laced couple who let loose on a 2020 drama that casts her as Deb, a mother “You’re the Worst,” and William Jackson with his conscience and an assortment of week of uninhibited fun and debauchery who must help her addict daughter Molly Harper, “The Good Place”), who break up enemies as he tries to complete his latest after befriending a thrill-seeking couple (Mila Kunis, “Black Swan”) through four days before her sister’s wedding but decide job. -

BBDO Picks the Winners!

BBDO Picks the Winners! Once a year the advertising agency of BBDO picks what they consider the breakout hits for the upcoming fall TV season. Based on their highly regarded opinion BBDO picks six probable winners (they call them swimmers) for the season: Roswell and Angel are listed as probable breakthrough hits on the WB. Joss Whedon, creator of the hit series Buffy The Vampire Slayer, combines supernatural adventure and dark humor in the next chapter of the Buffy saga, Angel. The centuries-old vampire (David Boreanaz), cursed with a conscience, has left the small town of Sunnydale and taken up residence in the City of Angels. Between pervasive evil and countless temptations lurking beneath the city’s glittery facade, Los Angeles proves to be the ideal address for a fallen vampire looking to save a few lost souls. With the help of Buffy’s Cordelia (Charisma Carpenter), and a shadowy figure known as “The Whistler” (Glenn Quinn), Angel has one last chance to save his own soul by restoring hope to those impressionable young people locked in a losing battle with their own demons. It has been called the City of Dreams, and Angel has come to fight the nightmares. WB2 Tuesday 8-9pm following Buffy The Vampire Slayer Analogy: “Interview with the Vampire meets the WB” In the summer of 1947, residents of the tiny town of Roswell, New Mexico believed they witnessed the fiery crash of an alien spacecraft. The federal government maintains it never happened. Now, on the eve of the fifty-second anniversary, the town once again comes together to celebrate the historic event some call an ill- fated visit from the stars and others call a hoax. -

Roswell – Untersuchungen Zu Einer Mysteryserie Und Deren Literarische Adaptionen

Roswell – Untersuchungen zu einer Mysteryserie und deren literarische Adaptionen Diplomarbeit im Fach Kinder- und Jugendmedien Studiengang Öffentliches Bibliothekswesen der Fachhochschule Stuttgart – Hochschule der Medien Emmanuelle Susanne Grumer Erstprüfer: Prof. Dr. Horst Heidtmann Zweitprüfer: Prof. Dr. Manfred Nagl Bearbeitungszeitraum: 15. Juli 2002 bis 15. Oktober 2002 Stuttgart, Oktober 2002 Kurzfassung 2 Kurzfassung Jason Katims ist der Schöpfer der Serie Roswell, die das Thema meiner Diplomarbeit ist. Nach der Vorstellung der Buchserie Roswell High von Melinda Metz, wandte ich mich den Themen der Serie zu. Neben der Vorstellung der Charaktere und den Fakten war die Analyse der Einschaltquoten ebenfalls wichtig. Danach folgt ein Einblick in den Mythos Roswell, der Absturz eines angeblichen Ufos im Jahre 1947 und des Rätsels der Kontakte zu Außerirdischen. Der Vergleich der Serie Roswell zu Science-Fiction-, Mysteryserien und Romances zeigt die Unterschiede der Serie zu anderen Serien aus den genannten Genres. Nach Interviews mit Fans gibt meine Diplomarbeit einen kurzen Überblick über die Repräsentation im Internet. Die Vermarktung der Serie schließt einen Vergleich zwischen Fernsehserie und Buchserie ein. Schlagwörter: Roswell, Außerirdische, UFO – Absturz, Fernsehserie, Narrative Interview, Serienbegleitbuch Abstract Jason Katims is the creator of the TV serie Roswell, which is the theme of my final exam paper. According to the introduction of the serie Roswell High from Melinda Metz, I turn to the themes of the serial. Beside the introduction of the characters and the facts the analysis the TV rating was really important. After this the insight of the myth Roswell, the crash of an alleged UFO in the year of 1947, an the riddle of contacts to aliens followed. -

District to Replace Principal At

www.tooeletranscript.com THURSDAY TOOELETRANSCRIPT Students’ artwork hangs in elite show. See B1 BULLETIN March 16, 2006 SERVING TOOELE COUNTY SINCE 1894 VOL. 112 NO. 85 50 cents Forget Jazz, Miller is ready to race District to replace by Mark Watson STAFF WRITER principal at THS Eventually, Larry H. Miller may pursue other business ventures Westover let go, will finish out year in Tooele County, but his $75 by Jesse Fruhwirth million Miller Motorsports Park STAFF WRITER is just too important to him right Tooele High School will get a now to focus on much else. new leader next year. The super- Perhaps Miller needs some intendent of the Tooele County therapeutic relief from worrying School District has said Mike about the inconsistent play of Westover will finish out the cur- his Utah Jazz basketball play- rent year, but will not be back to ers. Perhaps deep down his big- serve as principal in the fall. gest thrill would be zipping along When pressed for comment, at 150 mph in one of his race school board vice president cars instead of sitting court side. Carol Jefferies confirmed the Perhaps his goal to open the rumors that had spread like wild- track next month is providing fire. She said Superintendent mixed emotions of questions still Michael Johnsen had decided he unanswered coupled with over- would not ask the second-year whelming excitement like that of Mike Westover principal to stay at the helm of a 3 year old on Christmas Eve. the district’s largest school. as “a great man, a great princi- Whatever the reason, In a later interview, Johnsen pal” but said he could not com- when Miller speaks about his himself said it was true. -

Universal Realty

Saturday, August 1, 2015 TV TIME East Oregonian Page 7C Television > Today’s highlights Talk shows So You Think You Can Pawn Stars 7:00 a.m. (19) KEPR KOIN CBS This 1:00 p.m. KPTV The Wendy Williams Morning Show Ben Lyons, movie critic, gives HIST 9:30 p.m. Dance (25) KNDU KGW Today Show Meryl sneak peek at summer’s must-see (11) KFFX KPTV 8:00 p.m. The crew reveals the items Streep on ‘Ricki and the Flash.’ movies; Chef George Duran. they’ve most coveted for them- (42) KVEW KATU Good Morning (19) KEPR KOIN The Talk The Stage and Street dancing America (59) OPB Charlie Rose teams find out who will be elimi- selves in this special edition. WPIX Maury Jennifer wants to prove to WPIX The Steve Wilkos Show Greg has nated from the competition in They include a motorcycle once her ex that he fathered her now four- a 19-year-old daughter and their bond year-old daughter. is shooting up heroin together. this new episode. Cat Deeley owned by Rick’s idol, Steve Mc- 7:30 a.m. LIFE The Balancing Act Topics 2:00 p.m. KOIN (42) KVEW The Doctors hosts as the remaining perform- Queen, and a diamond encrusted include online learning and fi nancial KGW The Dr. Oz Show Dr. Oz reveals 2004 New England Patriots Su- tips for stay at home moms. three main reasons why your scale is ers dance their hearts out in the 8:00 a.m. WPIX The Jerry Springer stuck and what you should be eating. -

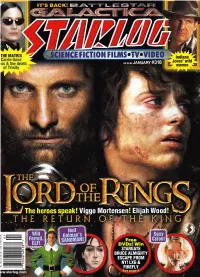

Starlog Magazine

THE MATRIX SCIENCE FICTION FILMS*TV*VIDEO Indiana Carrie-Anne 4 Jones' wild iss & the death JANUARY #318 r women * of Trinity Exploit terrain to gain tactical advantages. 'Welcome to Middle-earth* The journey begins this fall. OFFICIAL GAME BASED OS ''HE I.l'l't'.RAKY WORKS Of J.R.R. 'I'OI.KIKN www.lordoftherings.com * f> Sunita ft* NUMBER 318 • JANUARY 2004 THE SCIENCE FICTION UNIVERSE ^^^^ INSIDEiRicinE THISti 111* ISSUEicri ir 23 NEIL CAIMAN'S DREAMS The fantasist weaves new tales of endless nights 28 RICHARD DONNER SPEAKS i v iu tuuay jfck--- 32 FLIGHT OF THE FIREFLY Creator is \ 1 *-^J^ Joss Whedon glad to see his saga out on DVD 36 INDY'S WOMEN L/UUUy ICLdll IMC dLLIUII 40 GALACTICA 2.0 Ron Moore defends his plans for the brand-new Battlestar 46 THE WARRIOR KING Heroic Viggo Mortensen fights to save Middle-Earth 50 FRODO LIVES Atop Mount Doom, Elijah Wood faces a final test 54 OF GOOD FELLOWSHIP Merry turns grim as Dominic Monaghan joins the Riders 58 THAT SEXY CYLON! Tricia Heifer is the model of mocmodern mini-series menace 62 LANDniun OFAC THETUE BEARDEAD Disney's new animated film is a Native-American fantasy 66 BEING & ELFISHNESS Launch into space As a young man, Will Ferrell warfare with the was raised by Elves—no, SCI Fl Channel's new really Battlestar Galactica (see page 40 & 58). 71 KEYMAKER UNLOCKED! Does Randall Duk Kim hold the key to the Matrix mysteries? 74 78 PAINTING CYBERWORLDS Production designer Paterson STARLOC: The Science Fiction Universe is published monthly by STARLOG GROUP, INC., Owen 475 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. -

ONEITA PARKER Costume Designer Local 892&705 818.414.0470 [email protected] Oneitaparker.Net

ONEITA PARKER Costume Designer Local 892&705 818.414.0470 [email protected] oneitaparker.net F E AT U R E S (PARTIAL LIST ) D IRECTOR P R O D U CT I O N C O ./S TUDI O Love Or Whatever Rosser Goodman KGB Films Tyler Poelle, Joel Rush, Jennifer Elise Cox Without Men Gabriella Tagliavini Indalo Tales, LLC Eva Longoria, Christian Slater The Perfect Family Anne Renton Present Pictures Kathleen Turner, Emily Deschanel, Jason Ritter Pizza Man Joe Eckardt Rock On! Films Frankie, Shelley Long FDR: American Bad Ass Garett Braywith A Common Thread Barry Bostwick, Lin Shaye, Kevin Sorbo Darnell Dawkins: Mouth Guitar Legend Clayne Crawford A Common Thread Ross Patterson, Michael Raymond-James Meeting Spencer Malcolm Mowbray Meeting Spencer, LLC Jeffrey Tambor, Jesse Plemons, Yvonne Zima Stiletto Nick Vallelonga Vallelonga Productions International Stana Katic, Tom Berenger, Paul Sloan Spy School Mark Blutman Kosmic Film Entertainment Forrest Landis, AnnaSophia Robb, Rider Strong Caffeine John Cosgrove Steaming Hot Coffee, LLC Mena Suvari, Katherine Heigl Bachelor Party Vegas Eric Bernt Insomnia Entertainment Kal Penn, Jonathan Bennett , Donald Faison Perception Irving Schwartz Liquid Films/Perception Productions Piper Perabo, Monster Man Michael Davis Dream Entertainment/Lionsgate Eric Jungmann, Justin Urich, Aimee Brooks Stripped Down Elana Krausz Visualiner Studios Lisa Arturo, Bre Blaire, Ian Ziering Gacy Clive Saunders DEJ Prods./Peninsula Films/Rillington Prods. Mark Holton, Adam Baldwin, Charlie Weber T E L E VI S I O N (PARTIAL LIST ) C -

Product Guide

AFM PRODUCTPRODUCTwww.thebusinessoffilmdaily.comGUIDEGUIDE AFM AT YOUR FINGERTIPS – THE PDA CULTURE IS HAPPENING! THE FUTURE US NOW SOURCE - SELECT - DOWNLOAD©ONLY WHAT YOU NEED! WHEN YOU NEED IT! GET IT! SEND IT! FILE IT!© DO YOUR PART TO COMBAT GLOBAL WARMING In 1983 The Business of Film innovated the concept of The PRODUCT GUIDE. • In 1990 we innovated and introduced 10 days before the major2010 markets the Pre-Market PRODUCT GUIDE that synced to the first generation of PDA’s - Information On The Go. • 2010: The Internet has rapidly changed the way the film business is conducted worldwide. BUYERS are buying for multiple platforms and need an ever wider selection of Product. R-W-C-B to be launched at AFM 2010 is created and designed specifically for BUYERS & ACQUISITION Executives to Source that needed Product. • The AFM 2010 PRODUCT GUIDE SEARCH is published below by regions Europe – North America - Rest Of The World, (alphabetically by company). • The Unabridged Comprehensive PRODUCT GUIDE SEARCH contains over 3000 titles from 190 countries available to download to your PDA/iPhone/iPad@ http://www.thebusinessoffilm.com/AFM2010ProductGuide/Europe.doc http://www.thebusinessoffilm.com/AFM2010ProductGuide/NorthAmerica.doc http://www.thebusinessoffilm.com/AFM2010ProductGuide/RestWorld.doc The Business of Film Daily OnLine Editions AFM. To better access filmed entertainment product@AFM. This PRODUCT GUIDE SEARCH is divided into three territories: Europe- North Amerca and the Rest of the World Territory:EUROPEDiaries”), Ruta Gedmintas, Oliver -

Youth Culture and Television.Pdf

Television and Youth Culture Education, Psychoanalysis, and Social Transformation Series Editors: jan jagodzinski, University of Alberta Mark Bracher, Kent State University The purpose of this series is to develop and disseminate psychoanalytic knowl- edge that can help educators in their pursuit of three core functions of education. These functions are: 1) facilitating student learning; 2) fostering students’ personal development; and 3) promoting prosocial attitudes, habits, and behaviors in students (i.e., those opposed to violence, substance abuse, racism, sexism, homophobia, etc.). Psychoanalysis can help educators realize these aims of education by providing them with important insights into: 1) the emotional and cognitive capacities that are necessary for students to be able to learn, develop, and engage in prosocial behavior; 2) the motivations that drive such learning, development, and behaviors; and 3) the motivations that produce antisocial behaviors as well as resistance to learning and development. Such understanding can enable educators to develop pedagogical strategies and techniques to help students overcome psychological impediments to learning and development, either by identifying and removing the impediments or by helping students develop the ability to overcome them. Moreover, by offering an under- standing of the motivations that cause some of our most severe social problems— including crime, violence, substance abuse, prejudice, and inequality—together with knowledge of how such motivations can be altered, books -

University Faces Lawsuit from Injured Football Fan

Must-See TV? Drink and be merry? Scene takes a look at the downfalls In Focus examines the bar scene in South Bend Wednesday of NBC's fall Thursday night line-up. after student arrests at bars like Bridget page 10 McGuire's and Irish Connection. SEPTEMBER 29, page 3-4 1999 THE The Independent Newspaper Serving Notre Dame and Saint Mary's VOL XXXIII NO. 26 HTTP://OBSERVER.ND.EDU University faces lawsuit from injured football fan A...,..,oCJatcd Press LPtitia llayden from the "Notre Dame well a souvenir." Notre Dame contended that criminal acts of a third party. understands and benefits Hayden and her husband, the action of the person who INDIANAPOLIS The appeals court said William, were sitting behind injured Haydon was unfore A woman injunHl by some Notre Dame should have from the enthusiasm of the goal post in the south seeable and it thereforr, ono lunging for a ball in the foresePn that injury would the fans of its end zone Sept. 16,1995, owed no duty to anticipate it stands during a Notrn Dame likPiy rosult from people football game. " when one of the teams and protect her. football game can proceed lunging for footba.lls in the kicked a football toward the The appeals court said with lwr lawsuit against the stands and takr,n reasonable goal. there was evidr,nce of many University, the Indiana Court steps to prevent it. Hayden is Indiana Court of Appeals Several people lunged for prior incidents in which peo of Appeals ruled Tuesday. seeking unspecified dam the ball and one of them ple were jostled or injured by Tho dncision rovnrsed a agos.