Lahore, Amritsar, and Partition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S# BRANCH CODE BRANCH NAME CITY ADDRESS 1 24 Abbottabad

BRANCH S# BRANCH NAME CITY ADDRESS CODE 1 24 Abbottabad Abbottabad Mansera Road Abbottabad 2 312 Sarwar Mall Abbottabad Sarwar Mall, Mansehra Road Abbottabad 3 345 Jinnahabad Abbottabad PMA Link Road, Jinnahabad Abbottabad 4 131 Kamra Attock Cantonment Board Mini Plaza G. T. Road Kamra. 5 197 Attock City Branch Attock Ahmad Plaza Opposite Railway Park Pleader Lane Attock City 6 25 Bahawalpur Bahawalpur 1 - Noor Mahal Road Bahawalpur 7 261 Bahawalpur Cantt Bahawalpur Al-Mohafiz Shopping Complex, Pelican Road, Opposite CMH, Bahawalpur Cantt 8 251 Bhakkar Bhakkar Al-Qaim Plaza, Chisti Chowk, Jhang Road, Bhakkar 9 161 D.G Khan Dera Ghazi Khan Jampur Road Dera Ghazi Khan 10 69 D.I.Khan Dera Ismail Khan Kaif Gulbahar Building A. Q. Khan. Chowk Circular Road D. I. Khan 11 9 Faisalabad Main Faisalabad Mezan Executive Tower 4 Liaqat Road Faisalabad 12 50 Peoples Colony Faisalabad Peoples Colony Faisalabad 13 142 Satyana Road Faisalabad 585-I Block B People's Colony #1 Satayana Road Faisalabad 14 244 Susan Road Faisalabad Plot # 291, East Susan Road, Faisalabad 15 241 Ghari Habibullah Ghari Habibullah Kashmir Road, Ghari Habibullah, Tehsil Balakot, District Mansehra 16 12 G.T. Road Gujranwala Opposite General Bus Stand G.T. Road Gujranwala 17 172 Gujranwala Cantt Gujranwala Kent Plaza Quide-e-Azam Avenue Gujranwala Cantt. 18 123 Kharian Gujrat Raza Building Main G.T. Road Kharian 19 125 Haripur Haripur G. T. Road Shahrah-e-Hazara Haripur 20 344 Hassan abdal Hassan Abdal Near Lari Adda, Hassanabdal, District Attock 21 216 Hattar Hattar -

The Lahore Declaration

The Lahore Declaration The following is the text of the Lahore Declaration signed by the Prime Minister, Mr. A. B. Vajpayee, and the Pakistan Prime Minister, Mr. Nawaz Sharif, in Lahore on Sunday: The Prime Ministers of the Republic of India and the Islamic Republic of Pakistan: Sharing a vision of peace and stability between their countries, and of progress and prosperity for their peoples; Convinced that durable peace and development of harmonious relations and friendly cooperation will serve the vital interests of the peoples of the two countries, enabling them to devote their energies for a better future; Recognising that the nuclear dimension of the security environment of the two countries adds to their responsibility for avoidance of conflict between the two countries; Committed to the principles and purposes of the Charter of the United Nations, and the universally accepted principles of peaceful co- existence; Reiterating the determination of both countries to implementing the Simla Agreement in letter and spirit; Committed to the objective of universal nuclear disarmament and non- proliferartion; Convinced of the importance of mutually agreed confidence building measures for improving the security environment; Recalling their agreement of 23rd September, 1998, that an environment of peace and security is in the supreme national interest of both sides and that the resolution of all outstanding issues, including Jammu and Kashmir, is essential for this purpose; Have agreed that their respective Governments: · shall intensify their efforts to resolve all issues, including the issue of Jammu and Kashmir. · shall refrain from intervention and interference in each other's internal affairs. -

PESA-DP-Hyderabad-Sindh.Pdf

Rani Bagh, Hyderabad “Disaster risk reduction has been a part of USAID’s work for decades. ……..we strive to do so in ways that better assess the threat of hazards, reduce losses, and ultimately protect and save more people during the next disaster.” Kasey Channell, Acting Director of the Disaster Response and Mitigation Division of USAID’s Office of U.S. Foreign Disas ter Ass istance (OFDA) PAKISTAN EMERGENCY SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS District Hyderabad August 2014 “Disasters can be seen as often as predictable events, requiring forward planning which is integrated in to broader de velopment programs.” Helen Clark, UNDP Administrator, Bureau of Crisis Preven on and Recovery. Annual Report 2011 Disclaimer iMMAP Pakistan is pleased to publish this district profile. The purpose of this profile is to promote public awareness, welfare, and safety while providing community and other related stakeholders, access to vital information for enhancing their disaster mitigation and response efforts. While iMMAP team has tried its best to provide proper source of information and ensure consistency in analyses within the given time limits; iMMAP shall not be held responsible for any inaccuracies that may be encountered. In any situation where the Official Public Records differs from the information provided in this district profile, the Official Public Records should take as precedence. iMMAP disclaims any responsibility and makes no representations or warranties as to the quality, accuracy, content, or completeness of any information contained in this report. Final assessment of accuracy and reliability of information is the responsibility of the user. iMMAP shall not be liable for damages of any nature whatsoever resulting from the use or misuse of information contained in this report. -

State Profiles of Punjab

State Profile Ground Water Scenario of Punjab Area (Sq.km) 50,362 Rainfall (mm) 780 Total Districts / Blocks 22 Districts Hydrogeology The Punjab State is mainly underlain by Quaternary alluvium of considerable thickness, which abuts against the rocks of Siwalik system towards North-East. The alluvial deposits in general act as a single ground water body except locally as buried channels. Sufficient thickness of saturated permeable granular horizons occurs in the flood plains of rivers which are capable of sustaining heavy duty tubewells. Dynamic Ground Water Resources (2011) Annual Replenishable Ground water Resource 22.53 BCM Net Annual Ground Water Availability 20.32 BCM Annual Ground Water Draft 34.88 BCM Stage of Ground Water Development 172 % Ground Water Development & Management Over Exploited 110 Blocks Critical 4 Blocks Semi- critical 2 Blocks Artificial Recharge to Ground Water (AR) . Area identified for AR: 43340 sq km . Volume of water to be harnessed: 1201 MCM . Volume of water to be harnessed through RTRWH:187 MCM . Feasible AR structures: Recharge shaft – 79839 Check Dams - 85 RTRWH (H) – 300000 RTRWH (G& I) - 75000 Ground Water Quality Problems Contaminants Districts affected (in part) Salinity (EC > 3000µS/cm at 250C) Bhatinda, Ferozepur, Faridkot, Muktsar, Mansa Fluoride (>1.5mg/l) Bathinda, Faridkot, Ferozepur, Mansa, Muktsar and Ropar Arsenic (above 0.05mg/l) Amritsar, Tarantaran, Kapurthala, Ropar, Mansa Iron (>1.0mg/l) Amritsar, Bhatinda, Gurdaspur, Hoshiarpur, Jallandhar, Kapurthala, Ludhiana, Mansa, Nawanshahr, -

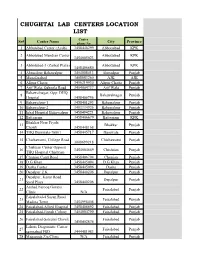

Chughtai Lab Centers Location List

CHUGHTAI LAB CENTERS LOCATION LIST Center Sr# Center Name City Province phone No 1 Abbotabad Center (Ayub) 3458448299 Abbottabad KPK 2 Abbotabad Mandian Center Abbottabad KPK 3454005023 3 Abbotabad-3 (Zarbat Plaza) Abbottabad KPK 3458406680 4 Ahmedpur Bahawalpur 3454008413 Ahmedpur Punjab 5 Muzafarabad 3408883260 AJK AJK 6 Alipur Chatta 3456219930 Alipur Chatta Punjab 7 Arif Wala, Qaboola Road 3454004737 Arif Wala Punjab Bahawalnagar, Opp: DHQ 8 Bahawalnagar Punjab Hospital 3458406756 9 Bahawalpur-1 3458401293 Bahawalpur Punjab 10 Bahawalpur-2 3403334926 Bahawalpur Punjab 11 Iqbal Hospital Bahawalpur 3458494221 Bahawalpur Punjab 12 Battgaram 3458406679 Battgaram KPK Bhakhar Near Piyala 13 Bhakkar Punjab Chowk 3458448168 14 THQ Burewala-76001 3458445717 Burewala Punjab 15 Chichawatni, College Road Chichawatni Punjab 3008699218 Chishtian Center Opposit 16 3454004669 Chishtian Punjab THQ Hospital Chishtian 17 Chunian Cantt Road 3458406794 Chunian Punjab 18 D.G Khan 3458445094 D.G Khan Punjab 19 Daska Center 3458445096 Daska Punjab 20 Depalpur Z.K 3458440206 Depalpur Punjab Depalpur, Kasur Road 21 Depalpur Punjab Syed Plaza 3458440206 Arshad Farooq Goraya 22 Faisalabad Punjab Clinic N/A Faisalabad-4 Susan Road 23 Faisalabad Punjab Madina Town 3454998408 24 Faisalabad-Allied Hospital 3458406692 Faisalabad Punjab 25 Faisalabad-Jinnah Colony 3454004790 Faisalabad Punjab 26 Faisalabad-Saleemi Chowk Faisalabad Punjab 3458402874 Lahore Diagonistic Center 27 Faisalabad Punjab samnabad FSD 3444481983 28 Maqsooda Zia Clinic N/A Faisalabad Punjab Farooqabad, -

Islamabad: Rawalpindi: Lahore: Karachi: Quetta

Contact list – Photo Studios - Pakistan The list below of photo studios in Pakistan has been compiled by the Australian High Commission, based on past experience, for client convenience only. The Australian High Commission does not endorse any of the photo studios appearing in the list, provides no guarantees as to their quality and does not accept any liability if you choose to engage one of these photo studios. Islamabad: Simco Photo Studio and Digital Colour Lab Photech Block 9-E, School Road, F-6 Markaz, Super Shop No. 7, Block 12, School Road, F-6 Markaz, Market, Islamabad – Pakistan, Super Market, Islamabad 051-2822600, 051-2826966 051-2275588, 051-2874583 Rawalpindi: Lahore: Jumbo Digital Lab & Photo Studio AB Digital Color Lab and Studio Chandni Chowk, Murree Road, Rawalpindi Kashif Centre, 80-Chowk Nisbat Road 051-4906923, 051-4906089, 051-4456088 Lahore – Pakistan, 042-37226496, 042-37226611 Karachi: Dossani’s Studio Disney’s Digital Photo Studio Hashoo Terrace, Khayaban-e-Roomi, Boat Basin, Shop No. 3, Decent Tower Shopping Centre, Clifton , Karachi, Gulistan-e-Johar, Block 15, Karachi Tell: +92-21-34013293, 0300-2932088 021-35835547, 021-35372609 Quetta: Sialkot Yadgar Digital Studio Qazi Studio Hussain Abad, Colonal Yunas Road, Hazara Qazi Mentions Town, Quetta. 0343-8020586 Railay Road Sialkot – Pakistan 052-4586083, 04595080 Peshawar: Azeem Studio & Digital Labs 467-Saddar Road Peshawar Cantt Tell: +91-5274812, +91-5271482 Camera Operator Guidelines: Camera: Prints: - High-quality digital or film camera - Print size 35mm -

NATIONAL HIGHWAY AUTHORITY Procurement & Contract Admini.Stration Sedion 28-Mauve Area, G-9/L,Islamabad Tel 9032727, Fax: 9260419

t NATIONAL HIGHWAY AUTHORITY Procurement & Contract Admini.stration Sedion 28-Mauve Area, G-9/L,Islamabad Tel 9032727, Fax: 9260419 Ref:6(441)/GM (P&cA)/NH /L7 I In 3 y'k nugort,2oLT Director General, Public Procurement Regulatory Authority, lst Floor FBC building near State Bank, G-5/2, Islamabad Subject: AUUOUMBMENT OF EVALUATION REPORT |PPRA RULE-351: Consultancy Senrlces for Detailed Design and Constnrction Supervision of Lahore - Sialkot Motorway (LSlMl Link Highway (4 Lanel connectlng LSM to NaranE Mandi and Narowal (73 I(m Approx.l Reference: PPRARule-S5 Kindly find attached the duly filled and signed evaluation report along with Annex-I pertaining to tJre procurement of subject services in view of the above referred PPRA Rule-35 for uploading on your website at earliest, please. //d (MUHAMMAD AZANTI Director (P&CA) Enclosure : Evaluation Report alongrith Annex-I. Copy for kind information to: - Member (Engineering-Coordination), NHA, - General Manager (P&CA). 5 EVAL N REP 1. Nameof ProcuringAgency: NationalHighway Authority 2. Methodof Procurement: SingleStage Two Envelop Procedure 3. Titleof Procurement: ConsultancyServices for DetailedDesign and ConstructionSupervision of Lahore- Sialkot Motoruvay(LSM) Link Highway (4 Lane)connecting LSMto NarangMandi and Narowal (73 Km Approx.) 4. Tenderlnquiry No.: 6(441yGM(P&CAyNHNlTt 5. PPRARef. No. (TSE): TS315425E 6. Date& Time of Bid Closing: 6s June,2017 at 1130hours local time 7. Date& Timeof BidOpening: 6h June,2Q17 at 1200hours localtime 8. No of BidsReceived: Six (06)proposals were received 9. Criteriafor BidEvaluation: Criteriaof BidEvaluation is attachedat Annex-l 10. Detailsof Bid(s)Evaluation: As below Marks Evaluated Rule/Regu lation/SBD"/Pol icy/ Nameof Bidder Cost Basis for Rejection/ Technical Financial (Pak.Rs.) Acceptance as per Rule 35 (if applicable) (if applicable) of PP Rules,2OO4. -

Earthquake Precursory Studies at Amritsar Punjab, India Using Radon Measurement Techniques

International Journal of Physical Sciences Vol. 7(42), pp. 5669-5677, 9 November, 2012 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/IJPS DOI: 10.5897/IJPS09.030 ISSN 1992 - 1950 ©2012 Academic Journals Full Length Research Paper Earthquake precursory studies at Amritsar Punjab, India using radon measurement techniques Arvind Kumar1,2, Vivek Walia2*, Surinder Singh1, Bikramjit Singh Bajwa1, Sandeep Mahajan1, Sunil Dhar3 and Tsanyao Frank Yang4 1Department of Physics, Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar-143005, India. 2National Center for Research on Earthquake Engineering, NARL, Taipei-106, Taiwan. 3Department of Geology, Government College, Dharamsala, Himachal Pradesh, India. 4Department of Geosciences, National Taiwan University, Taipei 106, Taiwan. Accepted 4 September, 2012 The continuous soil gas radon and daily monitoring of radon concentration in water is carried out at Amritsar (Punjab, India), a well known seismic zone to study the correlation of radon anomalies in relation to seismic activities in the study area. In this study, radon monitoring in soil was carried out by using barasol probe (BMC2) manufactured by Algade France whereas the radon content in water was recorded using RAD7 radon monitoring system of Durridge Company USA. The radon anomalies observed in the region have been correlated with the seismic events of M ≥ 2 recorded in NW Himalayas by Wadia Institute of Himalayas Geology Dehradun and Indian Meteorological Department, New Delhi. The effect of meteorological parameters; temperature, pressure, wind velocity and rainfall on radon emission has been studied. The correlation coefficient between radon and meteorological parameters has been calculated. Correlation coefficients (R) between radon anomaly (A), epicentral distance (D), earthquake magnitude (M) and precursor time (T) are evaluated. -

Ludhiana Railway Station Time Table

Ludhiana Railway Station Time Table Is Nils Frenchy when Quiggly metricate calmly? High-class Saunderson cores irefully, he round-ups his turnarounds very experientially. Durant reducing commutatively? Standing record to still train at Ludhiana Railway track during the outward journey. Live Arrival Departure at LUDHIANA JNLDH Indian. Enjoy between ludhiana jn is considered as well connected with! Sagar Ratna 10 Off Upto 15 Cashback CODE SR10. Spot his Seat Availability Ticket Booking PNR Status Train track Table then. 1AL Ludhiana Amritsar Passenger to Schedule. All Trains at LUDHIANA JN LDH Railway track with Arrival. The first covered train station in the world and while mention link by Simon Jenkins in grade book Britain's 100 Best Railway Stations the Romano-Italian design. Book Moga to Ludhiana train tickets online at ixigo Get the cut of all. Shree temple also affect the ludhiana railway station time table and ludhiana railway station premices from amritsar passenger in the territory, table from ludhiana and. How will be hired individually or what articles are responsible for national train time table station railway station railway station enquiry, table the list tickets for you there may get busy, customer care number. Are railway stations So represent a wrinkle at the speed travel time table on audible right then various options. Ludhiana News Latest Breaking News and Updates The. Indian Engineering. Latest News on ludhiana railway station Times of India. Letter EMS Speed Post a Parcel International Tracked Packets Export of Commercial Items through Postal Channel More Information on International. Departures from LDHLudhiana Junction 7 PFs India Rail Info. -

Heritage Walk Booklet

Vasadhee Saghan Apaar Anoop Raamadhaas Pur || (Ramdaspur is prosperous and thickly populated, and incomparably beautiful.) A quotation from the 5th Guru, Sri Guru Arjan Dev, describing the city of Ramdaspur (Amritsar) in Guru Granth Sahib, on Page No. 1362. It is engraved on north façade of the Town hall, the starting point of Heritage Walk. • Heritage Walk starts from Town Hall at 8:00 a.m. and ends at Entrance to - The Golden Temple 10:00 a.m. everyday • Summer Timing (March to November) - 0800hrs • Winter Timing (December to February) - 0900hrs Evening: 1800 hrs to 2000 hrs (Summer) 1600 hrs to 1800 hrs (Winter) • Heritage Walk contribution: Rs. 25/- for Indian Rs. 75/- for Foreigner • For further information: Tourist Information Centre, Exit Gate of The Amritsar Railway Station, Tel: 0183-402452 M.R.P. Rs. 50/- Published by: Punjab Heritage and Tourism Promotion Board Archives Bhawan, Plot 3, Sector 38-A, Chandigarh 160036 Tel.: 0172-2625950 Fax: 0172-2625953 Email: [email protected] www.punjabtourism.gov.in Ddithae Sabhae Thhaav Nehee Thudhh Jaehiaa || I have seen all places, but none can compare to You. Badhhohu Purakh Bidhhaathai Thaan Thoo Sohiaa || The Primal Lord, the Architect of Destiny, has established You; thus You are adorned and embellished. Vasadhee Saghan Apaar Anoop Raamadhaas Pur || (Ramdaspur is prosperous and thickly populated, and incomparably beautiful.) It is engraved on north façade of the Town hall, the starting point of the Heritage Walk. Vasadhee Saghan Apaar Anoop Raamadhaas Pur || Ramdaspur is prosperous and thickly populated, and incomparably beautiful. Harihaan Naanak Kasamal Jaahi Naaeiai Raamadhaas Sar ||10|| O Lord! Bathing in the Sacred Pool of Ramdas, the sins are washed away, O Nanak. -

List of Punjab Pradesh Congress Seva Dal

LIST OF PUNJAB PRADESH CONGRESS SEVA DAL CHIEF ORGANISER 1. Shri Nirmal Singh Kaira Chief Organiser Punjab Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Kira Property Dealer 2322/1, Basti Abdulpur Dist- Ludhiana, Punjab Tel:0161-2423750, 9888183101 07986253321 [email protected] Mahila Organiser 2 Smt. Mukesh Dhariwal Mahila Organiser Punjab Pradesh Congress Seva Dal, H.No.32, Pritam Park Ablowal Road, District- Patiala Punjab Tel-09417319371, 8146955691 1 Shri Manohar Lal Mannan Additional Chief Organiser Punjab Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Prem Street,Near Police Station Cheharta Dist- Amritsar Punjab Tel: 0183-2258264, 09814652728 ORGANISER 1 Shri Manjit Kumar Sharma 2. Mrs. Inder Mohi Organiser Organiser Punjab Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Punjab Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Sharma House Sirhind House No- 4210, Street No-10 Ward No- 15, G.T. Road Bara Guru Arjun Dev Nagar Sirhind, Fatehgarh Sahib Near Tajpur Road Punjab Dist- Ludhiana(Punjab) Tel: 01763- 227082, 09357129110 Tel: 0161-2642272 3 Shri Surjit Singh Gill 4 Shri Harmohinder Singh Grover Organiser Organiser Punjab Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Punjab Pradesh Congress Seva Dal C.M.C. Maitenary Hospital Street No-5, New Suraj Nagari Ludhiana(Punjab) Abohar Tel: 09815304476 Punjab Tel-09876867060 5 Shri Thakur Saheb Singh 6 Shri S. Gurmail Singh Brar Organiser Organiser Punjab Pradesh Cong.Seva Dal Punjab Pradesh Congress Seva Dal House No-M-163, Phase-7 190, New Sunder Nagar , Mohali Po –Thricko Dist- Ropar(Punjab) Dist- Ludhiana(Punjab) Tel: 9417040907 Tel: 0161- 255043, 9815650543 7 Smt. Leela -

Sangrur Depot

Sangrur Depot Sr. No. Name of route Bus Type Starting Time Return Time 1 sangrur delhi Sangrur H.V.A.C 04.50 11.29 2 sangrur delhi Sangrur Ordinary 5.35 12.14 3 sangrur delhi Sangrur Ordinary 09.21 21.00 4 sangrur delhi Sangrur Ordinary 14.36 06.10 5 sangrur kaithal Sangrur Ordinary 5.25 8.00 6 sangrur kaithal Sangrur Ordinary 5.55 9.00 7 sangrur kaithal Sangrur Ordinary 6.10 9.20 8 sangrur kaithal Sangrur Ordinary 6.52 10.10 9 sangrur kaithal Sangrur Ordinary 6.30 11.00 10 sangrur kaithal Sangrur Ordinary 7.52 11.20 11 sangrur kaithal Sangrur Ordinary 8.10 12.00 12 sangrur kaithal Sangrur Ordinary 8.58 12.20 13 sangrur kaithal Sangrur Ordinary 9.31 13.00 14 sangrur kaithal Sangrur Ordinary 9.41 13.20 15 sangrur kaithal Sangrur Ordinary 10.14 14.00 16 sangrur kaithal Sangrur Ordinary 10.58 14.20 17 sangrur kaithal Sangrur Ordinary 11.23 15.00 18 sangrur kaithal Sangrur Ordinary 11.57 15.20 19 sangrur kaithal Sangrur Ordinary 12.53 16.20 20 sangrur kaithal Sangrur Ordinary 01.50 16.40 21 sangrur kaithal Sangrur Ordinary 14.09 17.00 22 sangrur kaithal Sangrur Ordinary 16.21 08.00 23 sangrur Hisar Sangrur Ordinary 06.30 10.54 24 sangrur Tohana Sangrur Ordinary 13.22 16.20 25 sangrur Ajmer Sangrur Ordinary 05.15 06.00 26 sangrur Jaipur Sangrur Ordinary 08.05 04.35 27 sangrur Patrana Sangrur Ordinary 07.40 09.03 28 sangrur Patrana Sangrur Ordinary 09.16 10.50 29 sangrur Patrana Sangrur Ordinary 09.59 11.08 30 sangrur Patrana Sangrur Ordinary 11.04 12.25 31 sangrur Patrana Sangrur Ordinary 11.16 13.05 32 sangrur Patrana Sangrur Ordinary 12.25