Tampa Bay History 04/02 University of South Florida

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

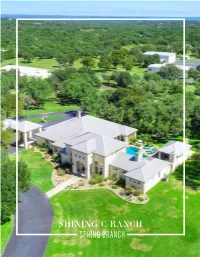

Spring Branch

SHINING C RANCH SPRING BRANCH Shining C Ranch is an incredibly rare find. This is a ready to go, true to form Luxury Ranch Commuter Estate of 36± acres, located in Spring Branch, just 20 minutes from San Antonio off Hwy 281 N and Hwy 46. This property is country living at its finest, with city conveniences now only minutes away! The main house is a one-story Austin limestone exterior home, with an open floor plan of approximately 4,800 square foot. It also boasts an open floor plan that is perfect for entertaining, featuring a 20’ tall ceiling in the entry area, four bedroom suites with four and half baths, a gourmet kitchen, a theater room, and way too many amenities to list. This makes it the perfect layout for comfortable living and easy entertaining. Surrounding the home and providing excellent views are the floor to ceiling windows that overlook a large pool with a built-in waterfall, patio, outdoor kitchen and cooking area, a fire pit, and a cabana with a three-quarter bath. The property also includes two electric entry gates finished in rock, a paved drive, and elegant outdoor lighting. Other structures and improvements include a 70x70 insulated hangar, eight stall horse barn with large tack room and tons of storage, a drive through workshop with three bedroom apartment, paved roads, two water wells with 20,000 gallons of water storage, dog kennels, and a half acre dog play pen. This is a rare and unique opportunity to have the best of the best. Don’t you deserve the best? Horse Barn // Insulated Hangar // Workshop with Apartment -

CRMLS , Inc. 1 *Blue Items Are Required

Paragon Residential Listing Input Form CRMLS , Inc. 1 *Blue Items are Required. ( # ) denotes Maximum # of Items that can be checked) **Green Items Required if Mobile Home has been selected ***Will populate the Mandated Remarks Field automatically *Agent ID:__________ ___________________________________Agent 2 ID: ______________ *Office ID:__________ _______________________________ Listing Agent # Agent Name 2nd Listing Agent ID# Listing Office # Office Name ____/_____/_____ ____/_____/_____ ________________ _________(Y/N) _________________ *List Date * Expiration Date *High List Price *** Variable Range *Low List Price *Assessors Parcel # Listing _______________ _____________________________________ ____________ ________ __________________ _____________ _________ *House Number # *Street Name Post Direction Unit#/Space# *City (Auto Fill from Tax Record) *County *Zip Code _______ _________ Map Code:____/____/___ *Community:_________________ *Neighborhood_________________*Cross ST(S)____________________ *State *Country Thomas Bros Page Column Row Table Driven 30 Characters *Complex/Park_________________________ *BR _______ ________ *BA________ *BA 1/2______ _____________ _______ _________ # Bedrooms *#Optinl Bdrms # Full Bathrooms # of 1/2 Baths Estimated SQ. FT. Zoning *Year Built (which doesn't include Detached Guest House) *CBB%________ *CBB$_______ *CVR Listing Service: Compensation to Compensation to Variable Commission _____(Y/N) *Entry Only: _____(Y/N) *Limited Service: ______ (Y/N) *Short Sale:____(Y/N) Buyers Broker % Buyers Broker -

Calendar 07.22.19

Spiritual , Intellectual, Physical, Social Monday, July 22 Tuesday, July 23 Wednesday, July 24 Thursday, July 25 Friday, July 26 Saturday, July 27 Sunday, July 28 6:00 - 11:00 am OPEN SWIM 6:00 - 8:00 am OPEN SWIM 6:00 - 11:00 am OPEN SWIM 6:00 - 8:00 am OPEN SWIM 6:00 - 11:00 am OPEN SWIM 2:00 - 10:00 pm -POOL 11:00 am - 10:00 pm -POOL 12:30 - 10 pm -POOL 11:00 am - 10:00 pm -POOL 12:30 - 10 pm -POOL All Day Open Swim - Pool All Day Open Swim - Pool 8:00-10:00 Coffee - WC, BI 8:00-10:00 Coffee - WC, RI 8 - 10 Coffee - WC, VI PATIO 6:30 St. Mary’s Lab - RPDR 8 - 10 Coffee - WC PATIO , BI 8:00-10:00 Coffee - WC, BI 2:30 Table Games - BI 8:10 Stretch & Flex - BS 9:00 Water Blast - Pool 8:10 OUTDOOR Stretch & 7:00 St. Mary’s Lab - HC Flex - meet in Ridge lobby 8:10 Stretch & Flex – BS 1:00 Men’s Billiards - GR 8:30 Women’s Circuit - IFC 10:00 Water Fusion - Pool 8:00-10:00 Coffee - WC, BI 8:30 Women’s Circuit - IFC 8:30 Women’s Circuit - IFC 2:00 Color My World - BI 9:00 Strength Training - IFC 9:00 Water Blast - Pool 3:15 Afternoon Swing - VI 10:00 Ladies Billiards - GR 8:30-11:15 Drop-in hours for 6:00 Worship Service 9:10 Strength Training - BS White River Knife & Tool 9:30 Creative Writing - RPDR 10:30 Feldenkrais - BS Blood Pressure Checks - HC in Centre Place 9:50 Circuit Training - BS 11:15 Balance & Core - IFC Tour & Lunch 10:00 Water Fusion - Pool 9:00 Strength Training - IFC Singles’ Potluck w/ Rev. -

Brunswick-Catalog.Pdf

THE BRUNSWICK BILLIARDS COLLECTION BRUNSWICKBILLIARDS.COM › 1-800-336-8764 BRUNSWICK A PREMIER FAMILY OF BRANDS It only takes one word to explain why all Brunswick brands are a cut above the rest, quality. We design and build high quality lifestyle products that improve and add to the quality of life of our customers. Our industry-leading products are found on the water, at fitness centers, and in homes in more than 130 countries around the globe. Brunswick Billiards is our cornerstone brand in this premier family of brands in the marine, fitness, and billiards industries. BRUNSWICK BILLIARDS WHERE FAMILY TIME AND QUALITY TIME MEET In 1845, John Moses Brunswick set out to build the world’s best billiards tables. Applying his formidable craftsmanship, a mind for innovation, boundless energy, and a passion for the game, he created a table and a company whose philosophy of quality and consistency would set the standard for billiard table excellence. Even more impressive, he figured how to bring families together. And keep them that way. That’s because Brunswick Billiards tables — the choice of presidents and sports heroes, celebrities, and captains of industry for over 170 years — have proven just as popular with moms and dads, children and teens, friends and family. Bring a Brunswick into your home and you have a universally-loved game that all ages will enjoy, and a natural place to gather, laugh, share, and enjoy each other’s company. When you buy a Brunswick, you’re getting more than an outstanding billiards table. You’re getting a chance to make strong and lasting connections, now and for generations to come. -

Pool and Billiard Room Application

City of Northville 215 West Main Street Northville, Michigan 48167 (248) 349-1300 Pool and Billiard Room Application The undersigned hereby applies for a license to operate a Commercial Amusement Device under the provisions of City of Northville Ordinance Chapter 6, Article II. Billiard and Pool Rooms. FEES: Annual Fee – 1st table $50 and $10 each additional table iChat fee $10 per applicant/owner Late Renewal – double fee Please reference Chapter 6, Article II, Billiard and Pool Rooms, Sec. 6-31 through 6-66 for complete information. Applications must be submitted at least 30 days prior to the date of opening of place of business. Applications are investigated by the Chief of Police and approved or denied by the City Council. Billiard or pool room means those establishments whose principal business is the use of the facilities for the purposes described in the next definition. Billiards means the several games played on a table known as a billiard table surrounded by an elastic ledge on cushions with or without pockets, with balls which are impelled by a cue and which includes all forms of the game known as carom billiards, pocket billiards and English billiards, and all other games played on billiard tables; and which also include the so-called games of pool which shall include the game known as 15-ball pool, eight-ball pool, bottle pool, pea pool and all games played on a so-called pigeon hole table. License Required No person, society, club, firm or corporation shall open or cause to be opened or conduct, maintain or operate any billiard or pool room within the city limits without first having obtained a license from the city clerk, upon the approval of the city council. -

D E F I N I T I O

BUSINESS LICENSE DEFINITIONS Acupressure/acupressure technicians Ambulance operator means any means, unless otherwise defined by person or entity who for any monetary the State of California, the stimulation or other consideration, or as an or sedation of specific meridian points incident to any other occupation, and trigger points neat the surface of transports in one or more ambulances the body by the use of pressure applied one or more persons needing medical by an acupressurist in order to prevent attention or services. or modify the perception of pain or to normalize physiological functions, Ambulance vehicle means a motor including pain control, in the treatment vehicle specially constructed, Billiard room means any place open of certain diseases or dysfunctions of modified, equipped, or arranged for the to the public where billiards, bagatelle the body. purpose of transporting sick, injured, or pool is played, or in which any convalescent, infirm, or otherwise billiard, bagatelle or pool table is Adult business means any business incapacitated persons, authorized by kept and persons are permitted to which, because minors are excluded the state as an emergency vehicle, play or do play thereon, whether any by virtue of their age as a prevailing and used, or having the potential compensation or reward is charged for business practice, is not customarily for being used, in emergency or the use of such table or not. “Billiard open to the general public, including, nonemergency medical service to the room” does not include a place having but not limited to, an adult arcade, public, regardless of level of service. not more than one coin-operated adult bookstore, adult theater, cabaret, An ambulance includes a ground pool or billiard table, which table is love parlor, model studio, nude studio, ambulance and EMS Aircraft. -

Fort Myers: from Rafts to Bridges in Forty Year

Tampa Bay History Volume 9 Issue 1 Article 5 6-1-1987 Fort Myers: From Rafts to Bridges in Forty Year Nell Colcord Weidenbach Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/tampabayhistory Recommended Citation Weidenbach, Nell Colcord (1987) "Fort Myers: From Rafts to Bridges in Forty Year," Tampa Bay History: Vol. 9 : Iss. 1 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/tampabayhistory/vol9/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Tampa Bay History by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Weidenbach: Fort Myers: From Rafts to Bridges in Forty Year This raft was used to ferry passengers at Ft. Thompson or Ft. Denaud. Photograph courtesy of the Fort Myers Historical Museum. FORT MYERS: FROM RAFTS TO BRIDGES IN FORTY YEARS by Nell Colcord Weidenbach The Caloosahatchee, a gem among rivers, is a familiar sight to motorists approaching South Florida via the Gulf coast. Since Florida was first burped up from the briny deep in some vague prehistoric era, the wide blue waters of the “River Beautiful” have been drifted upon, poled across, swum in, fought for, used and misused. The pirate “Black Caesar” knew the river well. Ponce de Leon explored it greedily. Seminoles and soldiers played cat and mouse in its coves for many years. For centuries, anybody who wanted to cross the river in the vicinity of today’s Fort Myers was forced to swim or float, like the ’gators and the manatees, in its shallow waters. -

Buildings Around Campus

Buildings Around Campus The Daniel Library was constructed in 1960 and is named in honor of the late Charles E. Daniel, Citadel 1918, and the late R. Hugh Daniel, Citadel 1929, both distinguished Citadel men who were lifelong benefactors of the college. The men established the Daniel International Corporation - at one time the third largest construction company in the world. The main library collection contains more than 1,128,798 books, bound periodicals, and government documents and pamphlets. Facilities include a 12,000 volume reference collection and 449,390 microfilm and microfilm readers. Wireless internet is accessible from most major seating areas of the first and second floors. Eight Citadel murals and portraits of The Citadel's superintendents, presidents (a term used after 1922), and distinguished alumni are featured on the interior walls. Summerall Chapel was erected during 1936-1937. Cruciform in design, the Chapel is a shrine of religion, patriotism, and remembrance. From the air the red clay tile roof forms a cross. It was designed in the spirit of 14th century Gothic. The furniture throughout is plain-sawed Appalachian Mountain white oak stained cathedral brown. The ceiling and timbering are pine. The lighting fixtures are handcrafted wrought iron throughout. Hanging from the walls are flags from the 50 states and the territories. The Chapel is in use year round with weekly religious services and weddings. The Grave of General Mark W. Clark. By his choice, and with the approval of the Board of Visitors and the General Assembly of South Carolina, General Mark W. Clark was buried on The Citadel campus. -

Meeting Rooms Fact Sheet

MEETING ROOM OPTIONS Room Dimensions & Capacities CAPACITY Dimensions Area Total Ceiling Height Boardroom Theatre Style Cabaret Classroom U- Shape Banquet Daylight Natural Blackout Facilities Room Name 23.1m x ✓ ✓ Grand Hall 265.7sqm 4.95m 72 200 120 140 70 180 11.5m ✓ ✓ Grand Hall I 10m x 11m 110sqm 4.95m 36 60 40 30 26 60 ✓ ✓ Grand Hall II 13m x 11m 143sqm 4.95m 46 120 80 72 40 120 Domed ✓ Orangery 11.7m x 9.9m 115.8sqm - 140 - 36 - 50 - ceiling ✓ Falcon Room 7.4m x 5.8m 42.9sqm 4.0m 20 35 18 18 -- - ✓ Mews Room 5.3m x 5.8m 30.7sqm 4.0m 12 ----- - L Shape ✓ Committee Room 5.8m x 5.5m 3.3m 10 ----- - 27sqm Vaulted ✓ Old Kitchen 8.0m x 7.5m 60sqm ceiling ----- 36 - 5.3m ✓ ✓ Harborough Room 9.9m x 5.6m 55.4sqm 5.3m 24 40 - - - 24 ✓ ✓ Billiard Room 6.7m x 6.6m 44.2sqm 5.3m 16 ---- 16 ✓ Morning Room 6.0m x 5.4m 32.4sqm 5.3m 8 30 --- 10 - ✓ Gilt Room 5.8m x 5.8m 33.6sqm 5.3m 8 ----- - Vaulted ✓ Pavilion 15m x 15m 75sqm 12 36 24 8 10 36 - ceiling ROOM PLANS & FACILITIES 23.1m GARDEN KITCHEN & SERVICE GRAND HALL THE ORANGERY TACK ROOM GRAND GRAND BAR HALL I HALL II LOBBY CLOAKROOM ENTRANCE (Width 2.05m) MAIN DRIVE GRAND HALL Room Details: Location: Adjoining the Light dimmer switch / 1 x main house and Telephone point / Easy access to Orangery main house / Blackout facility / Access: Direct from the Satellite kitchen / Interconnects main drive / Ideal with the Orangery for vehicular access: 3.0m x 2.04m Power: 3 phase 24 x 13 amp sockets ORANGERY Room Details: Location: Adjoining the 1 x telephone point / Private bar Grand Hall / Air conditioning / Cloakroom Access: Direct to gardens facilities / Front door leading and Main Drive to main drive / French doors leading to terrace and gardens Power: 4 x 13 amp sockets ROOM PLANS & FACILITIES W.C. -

Billiard Halls

Billiard halls can scarcely imagine any properly furnished hotel or modern public house without its billiard room’. At both the Grade II listed Boleyn Tavern, Barking Road (right), designed for the Cannon Brewery by WG Shoebridge and HW Rising, opened in 1900, and the Grade II* Salisbury Hotel, Green Lanes (below right), built by John Cathles Hill and opened in 1899, painted glass roof lights were designed to shed light onto billiard tables below. The effect was stunning. But London’s breweries positively alas what billiard players preferred threw themselves onto the billiards were dark rooms with lights slung bandwagon in the 1890s, creating low over the table. Added to which an architectural legacy that, long affordable overhead electric lighting after the game dropped out of became available in around 1913. fashion, shines on in Victorian and Some pubs appear to have done Edwardian gin palaces to this day. well from billiards. But the majority Determined to prove, to the found they could never recoup their public and to local magistrates that initial outlay with a game so few pubs could offer more than just people could play at any one time. beer and skittles, the breweries Pubs also lost out to the new invested heavily, in some instances generation of billiard halls which devoting up to 40 per cent of a offered longer opening hours. pub’s floor space to the game. As Which is why there are no The Licensed Victualler reported billiard tables in London pubs any in 1900, around the same time as more, or at best, as at the Boleyn, the Crown and Greyhound opened a pool table, somewhat dwarfed in Dulwich Village (above), ‘One by its magnificent surrounds. -

Paper #103 FDOT Experience with PBES for Small

FDOT Experience with PBES for Small-Medium Span Bridges Steven Nolan, P.E, Florida Dept. of Transportation (1), (850) 414-4272, [email protected] Sam Fallaha, P.E, Florida Dept. of Transportation (1), (850) 414-4296, [email protected] Vickie Young, P.E, Florida Dept. of Transportation (1), (850) 414-4301, [email protected] (1) State Structures Design Office, 605 Suwannee St, Tallahassee FL. 32399 ABSTRACT In the last quarter century, some elaborate methods of accelerated bridge construction (ABC) have been explored and executed in Florida, predominately though necessity in the segmental construction. ABC techniques have also been applied to more traditional flat-slab and slab-on-girder bridges including: Prefabricated Bridge Elements and Systems (PBES), full size bridge moves, top down construction, and other efforts to minimize road user delays and environmental impacts. This paper focuses on four modest structural systems which were successfully implemented on FDOT construction projects since the initiation of FHWA’s Every Day Counts program. This discussion focuses on ABC structural systems for: Precast Intermediate Bent Caps, Precast Full-Depth Bridge Deck Panels, Prestressed Concrete Florida-Slab Beams, and Geosynthetic Reinforced Soil Integrated Bridge Systems. INTRODUCTION Florida has been heavily involved in accelerated bridge construction activities (ABC) since the middle of the last century, primarily driven for economic advantage, with efforts predominantly led by the precast concrete industry. In the last quarter century, some elaborate methods of accelerated bridge construction have been explored and executed in Florida, predominately though necessity in the post-tensioned (PT) segmental construction to provide economy through speed of fabrication and erection, to offset significant mobilization and setup cost, specialized PT subcontractors and equipment. -

Notes for Tour of Townsend Mansion, Home of the Cosmos

NOTES FOR TOUR OF TOWNSEND MANSION HOME OF THE COSMOS CLUB July 2015 Harvey Alter (CC: 1970) Editor Updated: Jean Taylor Federico (CC: 1992), Betty C. Monkman (CC: 2004), FOREWORD & ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS These notes are for docent training, both background and possible speaking text for a walking tour of the Club. The material is largely taken from notes prepared by Bill Hall (CC: 1995) in 2000, Ed Bowles (CC: 1973) in 2004, and Judy Holoviak (CC: 1999) in 2004 to whom grateful credit is given. Many of the details are from Wilcomb Washburn’s centennial history of the Club. The material on Jules Allard is from the research of Paul Miller, curator of the Newport Preservation Society. The material was assembled by Jack Mansfield (CC: 1998), to whom thanks are given. Members Jean Taylor Federico and Betty Monkman with curatorial assistant, Peggy Newman updated the tour and added references to notable objects and paintings in the Cosmos Club collection in August, 2009. This material was revised in 2010 and 2013 to note location changes. Assistance has been provided by our Associate Curators: Leslie Jones, Maggie Dimmock, and Yve Colby. Acknowledgement is made of the comprehensive report on the historic structures of the Townsend Mansion by Denys Peter Myers (CC: 1977), 1990 rev. 1993. The notes are divided into two parts. The first is an overview of the Club’s history. The second part is tour background. The portion in bold is recommended as speaking notes for tour guides followed by information that will be useful for elaboration and answering questions. The notes are organized by floor, room and section of the Club, not necessarily in the order tours may take.