Philippines 2017 Human Rights Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drug Recycling' Officers in the Recycling of for Operations (DRDO) in Cen- Leged Involvement in Illegal Seized Illegal Drugs

MDM MONday | SEPTEMBER 30, 2019 P3 TIT FOR TAT Go wants some US senators banned from PH over de Lima Senator Christopher Lawrence Go on Saturday said he will suggest to President Rodrigo Duterte an equal retaliatory action against US senators who want to ban Philippine government officials from their country for their involvement in the detention of Senator Leila de Lima. “I will suggest to President Duterte to ban American legislators from entering our country for interfering in our internal affairs. These senators think they know better than us in governing ourselves,” Go said. Significantly, the senator made the statement in his speech at the 118th Balangiga Day Commemoration in Balangiga, Eastern Samar on Saturday, September 28. The Balangiga encounter was a successful surprise attack carried out by Filipino fighters against US troops during the Philippine-American War. It is considered by historians as one of the greatest displays of the bravery of the Filipinos fighting for their freedom. Commenting on news that a US Senate panel had approved an amendment in an appropriations bill that will ban Philippine government officials involved in the detention of de Lima, Go had choice words for the US senators: “Nakakaloko kayo.” “I condemn this act by a handful US senators… It is an affront to our sovereignty and to our ability to govern ourselves. It unduly pressures our independent courts and disrespects the entire judicial process of the Philippines by questioning its competence,” he said. Go said the US senators who proposed the initiative must themselves also be banned from the Philippines. -

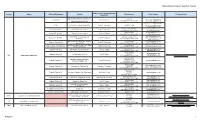

FOI Manuals/Receiving Officers Database

National Government Agencies (NGAs) Name of FOI Receiving Officer and Acronym Agency Office/Unit/Department Address Telephone nos. Email Address FOI Manuals Link Designation G/F DA Bldg. Agriculture and Fisheries 9204080 [email protected] Central Office Information Division (AFID), Elliptical Cheryl C. Suarez (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 2158 [email protected] Road, Diliman, Quezon City [email protected] CAR BPI Complex, Guisad, Baguio City Robert L. Domoguen (074) 422-5795 [email protected] [email protected] (072) 242-1045 888-0341 [email protected] Regional Field Unit I San Fernando City, La Union Gloria C. Parong (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4111 [email protected] (078) 304-0562 [email protected] Regional Field Unit II Tuguegarao City, Cagayan Hector U. Tabbun (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4209 [email protected] [email protected] Berzon Bldg., San Fernando City, (045) 961-1209 961-3472 Regional Field Unit III Felicito B. Espiritu Jr. [email protected] Pampanga (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4309 [email protected] BPI Compound, Visayas Ave., Diliman, (632) 928-6485 [email protected] Regional Field Unit IVA Patria T. Bulanhagui Quezon City (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4429 [email protected] Agricultural Training Institute (ATI) Bldg., (632) 920-2044 Regional Field Unit MIMAROPA Clariza M. San Felipe [email protected] Diliman, Quezon City (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4408 (054) 475-5113 [email protected] Regional Field Unit V San Agustin, Pili, Camarines Sur Emily B. Bordado (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4505 [email protected] (033) 337-9092 [email protected] Regional Field Unit VI Port San Pedro, Iloilo City Juvy S. -

Philippines's Constitution of 1987

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:44 constituteproject.org Philippines's Constitution of 1987 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:44 Table of contents Preamble . 3 ARTICLE I: NATIONAL TERRITORY . 3 ARTICLE II: DECLARATION OF PRINCIPLES AND STATE POLICIES PRINCIPLES . 3 ARTICLE III: BILL OF RIGHTS . 6 ARTICLE IV: CITIZENSHIP . 9 ARTICLE V: SUFFRAGE . 10 ARTICLE VI: LEGISLATIVE DEPARTMENT . 10 ARTICLE VII: EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENT . 17 ARTICLE VIII: JUDICIAL DEPARTMENT . 22 ARTICLE IX: CONSTITUTIONAL COMMISSIONS . 26 A. COMMON PROVISIONS . 26 B. THE CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION . 28 C. THE COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS . 29 D. THE COMMISSION ON AUDIT . 32 ARTICLE X: LOCAL GOVERNMENT . 33 ARTICLE XI: ACCOUNTABILITY OF PUBLIC OFFICERS . 37 ARTICLE XII: NATIONAL ECONOMY AND PATRIMONY . 41 ARTICLE XIII: SOCIAL JUSTICE AND HUMAN RIGHTS . 45 ARTICLE XIV: EDUCATION, SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, ARTS, CULTURE, AND SPORTS . 49 ARTICLE XV: THE FAMILY . 53 ARTICLE XVI: GENERAL PROVISIONS . 54 ARTICLE XVII: AMENDMENTS OR REVISIONS . 56 ARTICLE XVIII: TRANSITORY PROVISIONS . 57 Philippines 1987 Page 2 constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:44 • Source of constitutional authority • General guarantee of equality Preamble • God or other deities • Motives for writing constitution • Preamble We, the sovereign Filipino people, imploring the aid of Almighty God, in order to build a just and humane society and establish a Government that shall embody our ideals and aspirations, promote the common good, conserve and develop our patrimony, and secure to ourselves and our posterity the blessings of independence and democracy under the rule of law and a regime of truth, justice, freedom, love, equality, and peace, do ordain and promulgate this Constitution. -

Sandiganbayan Quezon City

REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES Sandiganbayan Quezon City SIXTH DIVISION PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, SB-16-CRM-0334 Plaintiff, For: Violation of Section 7(d) of R.A. No. 6713 SB-16-CRM-0335 For: Direct Bribery - versus - Present: FERNANDEZ, SJ, JL, ANGELITO DURAN SACLOLO, JR., Chairperson BT AL. MIRANDA, J". and Accused. VIVERO, J. Promulgated: J tf X- -X DECISION FERNANDEZ, SJ, J. Accused Angelito Duran Saclolo, Jr. and Alfredo G. Ortaleza stand charged for violation of Article 210 of the Revised Penal Code^ and of Section 7(d) of R.A. No. 6713,2 for demanding and accepting the amount of PhP300,000.00 / from Ma. Linda Moya of Richworld Aire and Technologie&V 'Republic Act No. 3815 2 Code ofConduct and Ethical Standardsfor Public Officials and Employees, Februaiy 20, 1989 DECISION People vs. Saclolo et at. Criminal Case Nos. SB-16-CRM-0334 to 0335 Page 2 of63 X X Corporation (Richworld), in consideration for the immediate passage of a Sangguniang Panlungsod Resolution authorizing the construction of Globe Telecoms cell sites in Cabanatuan City. The Information in SB'16-CRM'0334 reads: For: Violation ofR.A. No. 6713, Sec. 7(d) That on April 10, 2013 or sometime prior or subsequent thereto, in the City of Cabanatuan, Nueva Ecija, Philippines and within the jurisdiction of this Honorable Court, the accused, Angelito Duran Saclolo, Jr. and Alfredo Garcia Ortaleza, both public officers, being then a Member of the Sangguniang Panlungsod and concurrent Chairman of the Committee on Transportation and Communications and Secretaiy to the Sangguniang Panlungsod, respectively, of Cabanatuan City, Nueva Ecija, while in the performance of their official functions, committing the offense in relation to their office and taking advantage of their official positions, conspiring and confederating with one another, did then and there willfully, unlawfully and criminally accept the amount of Three Hundred Thousand Pesos (P300,000.00) from Ma. -

Legal and Constitutional Disputes and the Philippine Economy

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Sicat, Gerardo P. Working Paper Legal and constitutional disputes and the Philippine economy UPSE Discussion Paper, No. 2007,03 Provided in Cooperation with: University of the Philippines School of Economics (UPSE) Suggested Citation: Sicat, Gerardo P. (2007) : Legal and constitutional disputes and the Philippine economy, UPSE Discussion Paper, No. 2007,03, University of the Philippines, School of Economics (UPSE), Quezon City This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/46621 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Legal and Constitutional Disputes and the Philippine Economy By Gerardo P. Sicat∗ Abstract 0 I. Introduction..........................................................................................................1 II. The Constitutional framework of Philippine economic development policy since 1935 3 III. -

![THE HUMBLE BEGINNINGS of the INQUIRER LIFESTYLE SERIES: FITNESS FASHION with SAMSUNG July 9, 2014 FASHION SHOW]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7828/the-humble-beginnings-of-the-inquirer-lifestyle-series-fitness-fashion-with-samsung-july-9-2014-fashion-show-667828.webp)

THE HUMBLE BEGINNINGS of the INQUIRER LIFESTYLE SERIES: FITNESS FASHION with SAMSUNG July 9, 2014 FASHION SHOW]

1 The Humble Beginnings of “Inquirer Lifestyle Series: Fitness and Fashion with Samsung Show” Contents Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ................................................................ 8 Vice-Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ....................................................... 9 Popes .................................................................................................................................. 9 Board Members .............................................................................................................. 15 Inquirer Fitness and Fashion Board ........................................................................... 15 July 1, 2013 - present ............................................................................................... 15 Philippine Daily Inquirer Executives .......................................................................... 16 Fitness.Fashion Show Project Directors ..................................................................... 16 Metro Manila Council................................................................................................. 16 June 30, 2010 to June 30, 2016 .............................................................................. 16 June 30, 2013 to present ........................................................................................ 17 Days to Remember (January 1, AD 1 to June 30, 2013) ........................................... 17 The Philippines under Spain ...................................................................................... -

Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014

This event is dedicated to the Filipino People on the occasion of the five- day pastoral and state visit of Pope Francis here in the Philippines on October 23 to 27, 2014 part of 22- day Asian and Oceanian tour from October 22 to November 13, 2014. Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 ―Mercy and Compassion‖ a Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014 Contents About the project ............................................................................................... 2 About the Theme of the Apostolic Visit: ‗Mercy and Compassion‘.................................. 4 History of Jesus is Lord Church Worldwide.............................................................................. 6 Executive Branch of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Vice Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines .............................................................. 16 Speaker of the House of Representatives of the Philippines ............................................ 16 Presidents of the Senate of the Philippines .......................................................................... 17 Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the Philippines ...................................................... 17 Leaders of the Roman Catholic Church ................................................................ 18 Pope (Roman Catholic Bishop of Rome and Worldwide Leader of Roman -

Duterte's Killer Cops

2018 SOPA AWARDS NOMINATION BISHOPDUTERTE’Sfor INVESTIGATIVE KILLER REPORTING COPS Part 1 BLOOD ON THE STREET: The aftermath of what police said was a shoot-out with three drug suspects beneath MacArthur Bridge in central Manila in June. The three men were pronounced dead on arrival at hospital. REUTERS/Dondi Tawatao Duterte’s killer cops BY CLARE BALDWIN AND ANDREW R.C. MARSHALL JUNE 29 – DECEMBER 19 MANILA/ QUEZON CITY 2018 SOPA AWARDS INVESTIGATIVE REPORTING 1 DUTERTE’S KILLER COPS Part 1 It was at least an hour, according to resi- dents, before the victims were thrown into a truck and taken to hospital in what a police report said was a bid to save their lives. Old Balara’s chief, the elected head of the district, told Reuters he was perplexed. They were already dead, Allan Franza said, so why take them to hospital? An analysis of crime data from two of Metro Manila’s five police districts and interviews with doctors, law enforcement officials and victims’ families point to one answer: Police Philippine were sending corpses to hospitals to destroy evidence at crime scenes and hide the fact that they were executing drug suspects. police use Thousands of people have been killed since President Rodrigo Duterte took office on June 30 last year and declared war on what he called “the drug menace.” Among them were hospitals to the seven victims from Old Balara who were declared dead on arrival at hospital. A Reuters analysis of police reports covering hide drug the first eight months of the drug war reveals hundreds of cases like those in Old Balara. -

Ongoing Human Rights Violations and Impunity in the Philippines

“MY JOB IS TO KILL” ONGOING HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS AND IMPUNITY IN THE PHILIPPINES Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2020 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Photos of victims of killings lay on the floor at an event organized by Philippine (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) license. organization Rise Up for Life and for Rights. Some of the pictures bear the message “Hustisya!” – https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode “Justice!”, a common cry amidst the almost total climate of impunity for killings in the country. For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Metro Manila, 1 December 2019. Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this © Amnesty International material is not subject to the Creative Commons license. First published in 2020 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 35/3085/2020 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS SUMMARY 4 1. ONGOING VIOLATIONS IN THE "WAR ON DRUGS" 6 1.1 EXTRAJUDICIAL EXECUTIONS 7 1.2 UNRELENTING IMPUNITY 11 1.3 REFORMING A FLAWED APPROACH 13 2. -

The Evolving Paradigm of Filipino Prisoners' Artistic Performance As A

Journal of Tourism and Management Research 127 ISSN:2149-6528 Journal of Tourism and Management Research ISSN: 2149-6528 2017 Vol. 2, Issue.2 The Evolving Paradigm of Filipino Prisoners’ Artistic Performance as a Tourism Product Abstract This is an exploratory study aimed at determining whether the artistic performance of inmates in the national penitentiary may be considered as a tourism product. The performance began to gather worldwide attention with the showing of the dancing inmates on You Tube. The research was carried further by looking at performances which have been featured and are still being shown inside the Maximum and Medium Security Compounds of the country‟s prison.The methodology is a comparative analysis of literature related to tourism product and the formulation of an appropriate definition of the tourism product under study, it being intrinsic to the country. Following Smith‟s generic tourism product definition and the tourism production process, the analysis reinforced the very nature of prisoners‟ performance as a tourism product indeed. As such the paper serves to enlighten both prison and tourism stakeholders on the potential of the tourism product. Keywords: Tourism product, Inmates, Artistic performance, National penitentiary, Rehabilitation, Remediation ____________________________________ Emma Lina F. Lopez, PhD. Senior Lecturer, Asian Institute of Tourism University of the Philippines Commonwealth Avenue, Diliman. Quezon City, Metro Manila/Philippines 1101. Email: [email protected] Landline: (632)437-40-20 Mobile: +639198261817 Original Scientific Paper Lopez, E.L.F. 2017, Vol.2, No.2, pp.127-143. DOI:10.26465/ojtmr.2017229489 Journal of Tourism and Management Research 128 1. Introduction Just like Filipinos who dream to make it big in the global market, the Cebu dancing inmates have caught worldwide attention as their performance went viral in You Tube with their Michael Jackson dance drill moves. -

Rule on Access to Information About the Sandiganbayan

• .\, ABOUT THE SANDIGANBAYAN " :J:. Sandiqanbayan Centennial Building Commonwealth Avenue corner ~ ~ ;".. Batasan Road, Quezon City 1100 • Webslte sb judiciary gov ph • ...• Email: info sb uoiciary ov ph • Telefax 9514582 ~/ ,~ -/ ," "',,1 :\ G \' WHEREAS, pursuant to Section 28, Article 11of the 1987 Constitution, the State adopts and implements a policy of full public disclosure of all its transactions involving public interest, subject to reasonable conditions prescribed by law; WHEREAS, Section 7, Article III of the 1987 Constitution guarantees the right of the people to information on matters of public concern. Access to official records, and documents, and papers pertaining to official acts, transactions, or decisions, as well as to government research data used as basis for policy development, shall be afforded the citizen, subject to such limitations as may be provided by law; WHEREAS, the Judiciary has always maintained the principle of transparency and accountability in the court system, and full disclosure of its affairs pursuant to the aforesaid constitutional provision; WHEREAS, the Supreme Court promulgated resolutions defining the people's right to information, setting forth the extent thereof and explaining its limitations (on account of privilege and confidentiality) regarding matters and concerns affecting the operation of the Judiciary, its officers and employees; WHEREFORE, the Sandiganbayan hereby adopts and promulgates the followingRule on Access to Information: TITLEI .:.Preliminary Matters .:. Section 1. TITLE.- This set of rules shall be known and cited as "The Rule on Access to Information," hereinafter referred to as "Rule." Section 2. PURPOSE. - The Rule seeks to provide the guidelines, processes and procedures by which the Sandiganbayan shall deal with requests for access to information, as defined in this Rule, received pursuant to Section 7, Article III of the 1987 Constitution. -

Congressional Record O H Th PLENARY PROCEEDINGS of the 17 CONGRESS, FIRST REGULAR SESSION 1 P 907 H S ILIPPINE House of Representatives

PRE RE SE F N O T A E T S I V U E S Congressional Record O H th PLENARY PROCEEDINGS OF THE 17 CONGRESS, FIRST REGULAR SESSION 1 P 907 H S ILIPPINE House of Representatives Vol. 4 Monday, May 8, 2017 No. 86 CALL TO ORDER As Your children, we never cease to be faced with social, political, economic and environmental At 4:00 p.m., Deputy Speaker Frederick “Erick” challenges. We acknowledge that these challenges make F. Abueg called the session to order. us stronger and firmer in love and faith. But we need You always to be with us in order that we will not falter, THE DEPUTY SPEAKER (Rep. Abueg). The that we will not get lost, that we will not be afraid, and session is now called to order. that we will make only decisions that will follow Your will and Your wishes. NATIONAL ANTHEM We are a people who depend on You for guidance and wisdom. We pray that You will lead us always to THE DEPUTY SPEAKER (Rep. Abueg). Everybody the way of the righteous for the well-being of all. We is requested to rise for the singing of the National ask these in the name of the Almighty God. Amen. Anthem. THE DEPUTY SPEAKER (Rep. Abueg). The Dep. Everybody rose to sing the Philippine National Majority Leader is recognized. Anthem. REP. MERCADO. Mr. Speaker, I move that we THE DEPUTY SPEAKER (Rep. Abueg). Please defer the calling of the roll. remain standing for a minute of silent prayer and meditation—I stand corrected, we will have the THE DEPUTY SPEAKER (Rep.