Thesis-1998-H638d.Pdf (9.244Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Physicality of the Analogue by Duncan Robinson BFA(Hons)

Physicality of the Analogue by Duncan Robinson BFA(Hons) Submitted in the fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts. 2 Signed statement of originality This Thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution. To the best of my knowledge and belief, it incorporates no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgment is made in the text. Duncan Robinson 3 Signed statement of authority of access to copying This Thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Duncan Robinson 4 Abstract: Inside the video player, spools spin, sensors read and heads rotate, generating an analogue signal from the videotape running through the system to the monitor. Within this electro mechanical space there is opportunity for intervention. Its accessibility allows direct manipulation to take place, creating imagery on the tape as pre-recorded signal of black burst1 without sound rolls through its mechanisms. The actual physical contact, manipulation of the tape, the moving mechanisms and the resulting images are the essence of the variable electrical space within which the analogue video signal is generated. In a way similar to the methods of the Musique Concrete pioneers, or EISENSTEIN's refinement of montage, I have explored the physical possibilities of machine intervention. I am working with what could be considered the last traces of analogue - audiotape was superseded by the compact disc and the videotape shall eventually be replaced by 2 digital video • For me, analogue is the space inside the video player. -

The Development and Politics of Digital Media in Audiovisual Performance

OFFSCREEN :: Vol. 11, Nos. 8-9, Aug/Sept 2007 Projections: The Development and Politics of Digital Media in Audiovisual Performance By Mitchell Akiyama While music is often hailed as the harbinger of change, a privileged force 1 Jacques Attali claims that shifts in the at the vanguard of artistic invention, its performed incarnation has by comparison economy of music have anticipated corresponding shifts in the larger tended to be staunchly conservative.1 Music, in the Western tradition, is political economy throughout European history: “Music is prophecy. Its styles performed for (we could even say at) an audience. The first European concert and economic organization are ahead of th the rest of society because it explores, halls, built in the 18 century, placed the performer centre-stage with the audience much faster than material reality can, the entire range of possibilities of a given fanned around that point at 180°. It is a convention that has secured and code… For this reason musicians, even reproduced the cult of the star, the virtuoso.2 Even in contemporary music forms – when officially recognized, are dangerous, disturbing, and subversive.” rock, hip-hop, etc. – the star stands centre-stage. Western audiences are used to Jacques Attali. Noise: The Political Economy of Music. Minneapolis: watching performers use their voices or hit, pluck, scrape, and blow on objects University of Minnesota Press, 1985. P. 11. that make sound. These actions are codified, conventional, and, as such, musical. 2 See Attali on Liszt and “The Of course, the edges of this picture have occasionally been softened. Genealogy of the Classical Interpreter.” Compositions within the acousmatic tradition of electroacoustic music, for Noise, PP. -

Ninja Jamm Is an App That Allows You to Remix and Reimagine Songs and Tunes in an Intuitive Way

Ninja Jamm – Frequently Asked Questions What is Ninja Jamm? Ninja Jamm is an app that allows you to remix and reimagine songs and tunes in an intuitive way. It is not an app that simply allows you to mix two tunes together – Ninja Jamm presents you all the elements of a song, broken down into easy-to-access samples which include the original compositions and more besides. Through touch and gesture controls and the intuitive Ninja Jamm interface, you are able to take an original song and reimagine it as you wish. Strip the bass and drums away and turn Eyesdown by Bonobo into a haunting piano ballad. Slow down the tempo and add reverb to the drums and bass lines to turn Take It Back by Toddla T into a down and dirty dub tune… the possibilities are endless. Ninja Jamm offers the user a way to engage with music that they love like never before. Why just consume when you can interact and create? And all for less than the price of an iTunes single. Why is Ninja Jamm a first for the music industry? Ninja Jamm is more than just an app: it’ s a brand new, interactive format for the distribution and consumption of music. It’ s a new way for people to enjoy music and a new revenue stream for artists. It will sit alongside vinyl, CD, and digital MP3 downloads in all future Ninja Tune releases. Record labels - and in particular independents record labels such as Ninja Tune - constantly seek new ways to engage their audiences and to answer the challenges met by competition from streaming services, and the increase in consumption of music via YouTube search or even file shares. -

TEMPS D'images 2011 the Festival, Where Images Meet the Stage

TEMPS D’IMAGES 2011 The festival, where images meet the stage continues in April at garajistanbul! Image meets the stage in this festival. In the third year of the festival garajistanbul will be hosting different events and activities for those who wish to be up to date. Festival Temps D’images, which will be held between 09 April – 30 April 2011 in garajistanbul for the third time, focuses this year on the interaction between music and visual arts. The program ranges from electro, dubstep, techno and experimental house music to visual art performances, interdisciplinary theater and dance performances, 3‐D video mapping techniques, interactive placements, workshops and seminars about technology and art interaction carried out with Universities in Istanbul. This year, the festival is supported by the energetic, distinctive, spontaneous, and extroverted automotive brand MINI, which makes the festival even more exciting. The Festival Temps d’images is the perfect match between MINI, a brand for people who seek innovation and garajistanbul with it’s motto ‘Let yourself to the new!’ Announced as ‘one of the most thrilling, entertaining and charismatic DJ’s of the century’ by the Mixmag Magazine, especially well known for his midnight show at BBC Radio 1 and worldwide DJ Set concerts, Kissy Sell Out will be opening the festival with a pre‐concert by 2GET4. Other notable names in the Festival: Gudrun Gut feat Sonja Bender, Hexstatic, Zenzile, Taxi Val Mentek, Jutojo, Farfara, Lost Songs of Anatolia, Kolektif İstanbul… Other than the international performances, there are many local performances, such as KASSAS and aHHval, which include video, music and performance along with workshop and seminars by Selçuk Artut. -

Real-Time Audiovisuals

REAL-TIME AUDIOVISUALS DMA Summer Institute 2011 June 20 to 24 June 27 to July 1 instructor: Mattia Casalegno TA: email: [email protected] COURSE DESCRIPTION In this course students will engage with a set of software and hardware tools and techniques to produce and combine audiovisual content in real-time, creating works of live cinema, live media, and vjing. The emphasis will be on the use of real-time technologies instead of conventional linear editing tools. These technologies are more and more deployed in the art and entertainment indutries and in concerts, live shows, theatre productions, media art festivals and urban art events. Students will learn to shoot and produce original content, mix and edit in real time, and design generative applications reacting to sound and various control interfaces. Professional multi-platform software such as Resolume Avenue, Module8 and Cycling74 Max/Msp/Jitter will be introduced, with the context of some of the most influential artists working across the disciplines of live media performance. For this course, emphasis will be given to the relationship of real-time audiovisuals to architecture. The course will culminate with a collaborative project where a portion of the Broad Art Center building facade is entrusted to each student, with the prompt to use video-mapping techniques to engage the existent architecture with personal au- diovisual designs. The students will use the building’s architecture as a blank canvas for their unique live-media cre- ations. 1 WEEK SCHEDULE Day 1 - course presentation - introduction: peculiarities of real-time and linear editing: loop, cut, sampling and looping: add, mix and mash-up. -

Live Hard...Party Harder

ISSUE #12 OUR SPECIAL ONE YEAR ANNIVERSARY ISSUE. HAPPY BIRTHDAY US! LIVE HARD.... ....PARTY HARDER WARNING Before playing this game, read the Xbox 360® console, Xbox 360 Kinect® Sensor, and accessory manuals for important safety and health information. www.xbox.com/support. Important Health Warning: Photosensitive Seizures A very small percentage of people may experience a seizure when exposed to certain visual images, including flashing lights or patterns that may appear in video games. Even people with no history of seizures or epilepsy may have an undiagnosed condition that can cause “photosensitive epileptic seizures” while watching video games. Symptoms can include light-headedness, altered vision, eye or face twitching, jerking or shaking of arms or legs, disorientation, confusion, momentary loss of awareness, and loss of consciousness or convulsions that can lead to injury from falling down or striking nearby objects. Immediately stop playing and consult a doctor if you experience any of these symptoms. Parents, watch for or ask children about these symptoms—children and teenagers are more likely to experience these seizures. The risk may be reduced by being farther from the screen; using a smaller screen; playing in a well-lit room, and not playing when drowsy or fatigued. If you or any relatives have a history of seizures or epilepsy, consult a doctor before playing. Table of Contents 02 Getting Started 04 The Lost and Damned 06 The Ballad of Gay Tony 08 Credits 16 Warranty/Technical Support 1 Getting Started Game Controls Xbox LIVE Xbox 360 Controller Play anyone and everyone, anytime, anywhere on Xbox LIVE®. -

What Comes After Remix?

WHAT COMES AFTER REMIX? Lev Manovich [winter 2007] It is a truism today that we live in a “remix culture.” Today, many of cultural and lifestyle arenas - music, fashion, design, art, web applications, user created media, food - are governed by remixes, fusions, collages, or mash-ups. If post- modernism defined 1980s, remix definitely dominates 2000s, and it will probably continue to rule the next decade as well. (For an expanding resource on remix culture, visit remixtheory.net by Eduardo Navas.) Here are just a few examples of how remix continues to expand. In his 2004/2005-winter collection John Galliano (a fashion designer for the house of Dior) mixed vagabond look, Yemenite traditions, East-European motifs, and other sources that he collects during his extensive travels around the world. DJ Spooky created a feature-length remix of D.W. Griffith's 1912 "Birth of a Nation” which he appropriately named "Rebirth of a Nation." In April 2006 Annenberg Center at University of Southern California run a two-day conference on “Networked Politics” which had sessions and presentations a variety of remix cultures on the Web: political remix videos, anime music videos, machinima, alternative news, infrastructure hacks.1 In addition to these cultures that remix media content, we also have a growing number of software applications that remix data – so called software “mash-ups.” Wikipedia defines a mash-up as “a website or application that combines content from more than one source into an integrated experience.”2 At the moment of this writing (February 4, 2007), the web site www.programmableweb.com listed the total of 1511 mash-ups, and it estimated that the average of 3 new mash-ups Web applications are being published every day.3 1 http://netpublics.annenberg.edu/, accessed February 4, 2007. -

THE CLUB CHART 56 49 to the MAX/IT's MY TURN Steno Sleeping Bag Records I2in 57 — MY TELEPHONE (0-110 /14 )/BEATS& PIECES (MO BASS REM1X) (0-104-0)/FAT (PARTY &

4' 55 41 LOVER (MIXES) Roqui - ' US Nugroove I2in THE CLUB CHART 56 49 TO THE MAX/IT'S MY TURN Steno Sleeping Bag Records I2in 57 — MY TELEPHONE (0-110 /14 )/BEATS& PIECES (MO BASS REM1X) (0-104-0)/FAT (PARTY & BULLSHIT) i I12)/NO CONNECTION (126 /14 )/TRAK 22 (122)/PEOPLE HOLD ON (122A /STOP THIS CRAZY THING (0- 107 /12 )/(HEDMASTER MIX)(1073,3-01/DOCTORIN' THE HOUSE (SAY R MIX) (0-1 I7 /12 )/(I'M) IN DEEP (0-121 /14 -0)/MAKER BRAKE (1 00)/GREEDY'S BACK (0-105 )/DRAWMASTERS SQUEEZE (99)/WHAT'S THAT NOISE? (0-1 I 7/14 -0)/SMOKE 1 (0-98S/6.0)/THEME FROM 'REPORTAGE' (116 /12 -0)/WHICH DOCTOR? (0-1124/s-0) Coldcut Ahead Of Our Time LP/bonus I2in I I KEEP ON MOVIN' (CLUB MIX) Soul II Soul (featuring Caron Wheeler) 10 Records I2in 58 JUST A LITTLE BIT (MIXES) (1 I 9/34 )Total Science Jumpin' &Purnpin' I2in 2 7 PLANET E(MI XES)/DANCIN' MACHINE (ACID HOUSE REMIX)kc Flightt RCA I2in 59 71 VOODOO RAY (FRANKIE KNUCKLES/RICKY ROUGE REMIXES) A Guy Called Gerald 3 8 THAT'S HOW I'M LIVING (MIXES)/THE CHIEF Toni Scott Champion I2in US Warlock Records 12in 4 9 WHO'S IN THE HOUSE the Beatmasters with Merlin Rhythm King I2in 60 JUSTA LITTLE MORE (87½1/(SURRENDER MIX) (87')/7-8745) Fifth Of Heaven 5 3 MUSICAL FREEDOM (FREE AT LAST)(EXTENDED FREEDOM MIX) Paul Simpson featuring MixOut Records I2mn Adeva and introducing Carmen Marie Coolternpo I2in 61 97 I'M THE ONE (CHRIS PAUL DANCE REMIX)Pern 6 4 BACK TO LIFE —JAZZIE'S GROOVE/HAPPINESS (DUB)/AFRICAN DANCE/DANCE/ 62 68 1WANT YOU/SHE SAY KUFF (MIXES) SoundsSoun -4-: ,Weei MCA Records 12in nugráfive I lin HOLDIN' -

Dr Robert Christian Pepperell FRSA University Address: Robert

Dr Robert Christian Pepperell FRSA University address: Robert Pepperell Professor of Fine Art Fovolab Cardiff School of Art and Design Llandaff Campus Cardiff CF5 2YB, UK [email protected] www.robertpepperell.com Education: 2009 University of Wales, PhD. 1986-88 Slade School of Art, University ColleGe, London. 1983-86 Newport School of Art, 1st class BA(Hons) in Fine Art. 1982-83 Gloucestershire ColleGe of Art and TechnoloGy, Cheltenham. Foundation diploma. Teaching experience: 2009 to date: Professor of Fine Art, Cardiff School of Art and DesiGn. 2006-2009: Head of Fine Art, Cardiff School of Art and DesiGn, University of Wales Institute Cardiff. Responsible for leadinG BA (Hons) Fine Art department, MA Fine Art tuition and PhD supervision. 2004-2006: Senior Lecturer in Fine Art, School of Art & Performance, University of Plymouth. Responsibilities included leadership of paintinG and print department. research Group co-ordination, undergraduate and postGraduate teachinG and PhD/MPhil supervision. 1999-2006: Senior Lecturer, School of Art, Media and DesiGn, University of Wales ColleGe, Newport. Responsibilities included MA Fine Art proGramme leadership, research Group co-ordination, underGraduate teachinG in Fine Art, DesiGn and MPhil/PhD supervision. Academic manaGement tasks include course writinG, validation and marketinG. 1988-90: VisitinG Lecturer at Leicester Polytechnic, BA Fine Art. 1986-88: VisitinG Lecturer at Newport School of Art, BA Fine Art. Current positions: Co-Executive Editor of the journal Art & Perception -

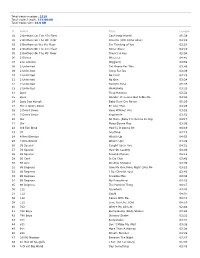

Total Tracks Number: 2218 Total Tracks Length: 151:00:00 Total Tracks Size: 16.0 GB

Total tracks number: 2218 Total tracks length: 151:00:00 Total tracks size: 16.0 GB # Artist Title Length 01 2 Brothers On The 4Th Floor Can't Help Myself 05:39 02 2 Brothers On The 4th Floor Dreams (Will Come Alive) 04:19 03 2 Brothers on the 4th Floor I'm Thinking of You 03:24 04 2 Brothers On The 4Th Floor Never Alone 04:10 05 2 Brothers On The 4th Floor There's A Key 03:54 06 2 Eivissa Oh La La 04:41 07 2 In a Room Wiggle It 03:59 08 2 Unlimited Get Ready For This 03:40 09 2 Unlimited Jump For Joy 03:39 10 2 Unlimited No Limit 03:28 11 2 Unlimited No One 03:24 12 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 05:36 13 2 Unlimited Workaholic 03:33 14 2pac Thug Mansion 03:32 15 2pac Wonder If Heaven Got A Ghetto 04:34 16 2pac Daz Kurupt Baby Dont Cry Remix 05:20 17 Three Doors Down Be Like That 04:25 18 3 Doors Down Here Without You 03:53 19 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 03:52 20 3lw No More (Baby I'm Gonna Do Rig 04:17 21 3lw Playa Gonna Play 03:06 22 3rd Eye Blind How Is It Gonna Be 04:10 23 3T Anything 04:15 24 4 Non Blondes What's Up 04:55 25 4 Non Blonds What's Up? 04:09 26 38 Special Caught Up In You 04:25 27 38 Special Hold On Loosely 04:40 28 38 Special Second Chance 04:12 29 50 Cent In Da Club 03:42 30 50 cent Window Shopper 03:09 31 98 Degrees Give Me One More Night (Una No 03:23 32 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 03:43 33 98 Degrees Invisible Man 04:38 34 98 Degrees My Everything 04:28 35 98 Degrees The Hardest Thing 04:27 36 112 Anywhere 04:03 37 112 Cupid 04:07 38 112 Dance With Me 03:41 39 112 Love You Like I Did 04:16 40 702 Where My Girls At 02:44 -

Magazine Palác Akropolis 09—12—2007

MaPAMagazine Palác Akropolis 09—12—2007 00_akromag_obalka.indd 64-1 9/28/07 11:58:23 AM OBSAH 02 –––––– Úvodní slovo 30-31 ––– Nová koncepce výstav ––––––––– Lubomír Schmidtmajer ––––––––– v Paláci Akropolis 03 –––––– Palác Akropolis Rozhovory ––––––––– Karel Haloun, Luděk Kubík, ––––––––– Jeroným Janíček ––––––––– Jaroslav Prokop 04-05 ––– Akropolis Live Music Awards 32-33 ––– Dan Bárta & Illustratosphere ––––––––– Pavel Ovesný 34 –––––– Křížem krážem Evropou 06-08 ––– Rozhovor: Spontánní 36-37 ––– Kytara napříč žánry 2007 ––––––––– a nepředvídatelní Soft Machine 38-39 ––– Reportáž: ––––––––– Aleš Opekar ––––––––– Když ve Skotsku prší divadlo 09 –––––– Tros Sketos ––––––––– Hanka Kubáčková 10-13 –––– Rozhovor: 40-41 ––– Reportáž: Hledání vize a talentů ––––––––– Sex, řád a budoucnost vesmíru/ ––––––––– Petra Ludvíková ––––––––– Kabaret Caligula 43 –––––– CD recenze ––––––––– Hanka Kubáčková ––––––––– Pavel Zelinka 14-15 –––– Rozhovor: Nejen má nesplněná přání/ 44-45 ––– Adrenalin na prknech, ––––––––– Josef Sedloň ––––––––– jež znamenají svět ––––––––– Ludmila Škrabáková ––––––––– Kateřina Dolenská 16 ––––––– David Sylvian 46-47 ––– EuroConnections 2007 17 ––––––– Ghostmother 48-51 ––– Program Paláce Akropolis 10-12/07 18-20 ––– Divadlo teď a tady 53-53 ––– Move European Festival ––––––––– Vladimír Hulec 54 –––––– Pekingská opera 21 ––––––– Hana & Hana 55-59 ––– Ohlédnutí za sezonou 2006/2007 22-26 ––– Respect Plus: podzim 2007 ––––––––– Petr Dorůžka 27 –––––– Other Music: Ex Music ––––––––– Petr Dorůžka 28-29 ––– Akropolismultimediale ––––––––– Tereza Kunová 00_akromag_obalka.indd 2-63 00_akromag_vnitrky.indd 01 9/28/07 12:08:1311:58:27 PMAM Změny vedoucí ke zkvalitnění diváckého zázemí bylo možno započít díky důvěře CNK PA v zámě- ry nového vedení Art Frame. Rekonstrukce v prů- běhu prázdnin vytvořila prostory nových toalet, čímž byla jejich kapacita ztrojnásobena. V realizač- PalácAkropolis ní návaznosti se dokončuje nový bar, šatna pro divá- ky se zvýšenou kapacitou a definitivně se dotváří interiér kavárny. -

U.K.'S Eclectic NO Tune Marks 10 Years with Boxed Set by RASHAUN HALL Own Thing," Explains Koala

Dance ARTISTS & MUSIC U.K.'s Eclectic NO Tune Marks 10 Years With Boxed Set BY RASHAUN HALL own thing," explains Koala. "It's rare says Koala, referring to labelmates always do well for us. It's great, and hits, and compiling from that," says NEW YORK -Individuality seems for a label to just let you develop as like Tobin, Cinematic Orchestra, DJ encouraging, that such an indepen- More. "We couldn't really do that to be a rare commodity in the music an artist. If you decide to do some- Vadim, and the Herbaliser. "There's dent label can now be celebrating its because we're always interested in industry today. With boy bands and thing completely different from the a consistency in terms of the people 10th anniversary." something new. So we went to the coming -of-age divas being signed left last thing you did, they support it. If doing what they want. People enjoy In preparing the "Xen Cuts" artists and asked them what they and right, it's become ever more dif- that about the label." wanted to do. We gathered all this ficult for experimental artists to find Notes More, "Plus, they are all material and then tried to figure out a label to call home. For this reason, very motivated artists. A lot of peo- what to use. At one point, we just U.K. -based label Ninja Tune remains ple send demos off and expect the said, `Fuck it, let's go for it.'" vital. record companies to fall all over Highlights of the 39 -track collec- Home to a wide variety of art- themselves, but that doesn't happen.