The River Endrick - Then and Now, Monitoring by Photography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Water Bus Loch Lomond 2013

Cabs – 01877 382587. 01877 – Cabs £56.00 £40.00 Family Contact J. Morgan Taxis – 01877 330496 and Crescent Crescent and 330496 01877 – Taxis Morgan J. Contact £14.00 £10.00 under & 16 Children allander C and Pier rossachs T . between available is £18.00 £13.00 Adult berfoyle A and tronachlachar S . In the Trossachs it it Trossachs the In . ay D Full hours CES U I 3 R P to p Inversnaid, Inversnaid, between available is service the or call us 01389 756251 01389 us call or direct regular bus service. In the Strathard area area Strathard the In service. bus regular direct www.canyouexperience.com/canoe_hire.php Strathard and Trossachs areas that have no no have that areas Trossachs and Strathard from hired be can canoes and boats Bicycles, This service is provided by Stirling Council for for Council Stirling by provided is service This OCH LL A B AT RE I H E L C Y C BI (has to be booked 24 hours in advance) in hours 24 booked be to (has ORT P TRANS E IV ONS P RES DEMAND £8.00 £6.00 under & 16 Children £18.00 £12.00 Adult next bus times. bus next ay D Full hours CES U I 4 R P to p txt2traveline for service SMS use also can You 01877 376366. 01877 m.trafficscotland.org websites. and cannot be accommodated. be cannot www.katrinewheelz.co.uk calling by or at mobile.travelinescotland.com mobile-friendly due to Health & Safety reasons, electric wheelchairs wheelchairs electric reasons, Safety & Health to due Cycle hire information and prices can be obtained obtained be can prices and information hire Cycle access public transport and traffic info on the the on info traffic and transport public access • weekend break weekend A discuss your particular requirements. -

Rowardennan Lodge Youth Hostel Rowardennan, by Drymen, Glasgow G63 0AR T: +44 (0)1360 870 259 E: [email protected]

Rowardennan Lodge Youth Hostel Rowardennan, By Drymen, Glasgow G63 0AR t: +44 (0)1360 870 259 e: [email protected] Rowardennan Youth Hostel, in the heart of Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park, sits in an idyllic location on the banks of Loch Lomond with unobstructed views and the West Highland Way passing by the gate. Rooms Catering Facilities Capacity 57: We offer a full catering service, • Lounge (with TV) overlooks the • 4 twin rooms (single beds) with continental and cooked loch and can seat 30 people breakfasts, packed lunches and • 1 double • Laundry is accessible evening meals for individuals • 1 triple (disabled access between 17.00-08.00. It has and groups with ensuite) 2 coin-operated washing and • 3 four-bedded Group meals need to be booked 2 drying machines • 4 six-bedded in advance, though individuals • Small drying room (free of may book upon arrival • 1 eight-bedded charge) Evening meals are served • Free internet/Wi-Fi access Family/private rooms are between 18.30-21.00 and is available available on request. Room breakfasts from 07.30-09.00 configurations may be subject to Security occasional change Self-catering All rooms have locks, but no There are 9 showers and 9 • Kitchen is open between lockers. There’s an additional toilets. There is one en-suite 06.00-10.30 and 13.30- security door between reception room. All rooms have washbasins midnight and has space and the main building for 10 people Reception Cycle rack outside available • 2 domestic ovens, 3 fridges for guests (please bring your -

Loch Lomond Loch Katrine and the Trossachs

Bu cxw 81 SON m m 0 OldBad on o 5 ey, L d n 1 S n/ r 7 ta mm St eet, Glea m Bu cxm 8c SON (INDIA) Lm rm War wzck Hom e For t Str eet Bom , . bay Bu cms a; SON (Gamma) m an Tor onto Pr oud bxGr eat Br itom by BlacM 8 8 0m h d., Gla:gow LIST OF I LLUSTRATIONS Fr ontzspzece Inch Cailleach Loch Lomond from Inver snaid nd o A hr a o ac Ben Venue a L ch c y, Tr ss hs d Pass o ac The Ol , Tr ss hs ’ Isl oc Katr ine Ellen s e, L h Glen Finglas or Finlas V IEW FROM BALLOCH BRI DGE Among the first of the featur es of Scotland which visitors to the country express a wish to see are the ” “ u n island reaches of the ! ee of Scottish Lakes , and the bosky narrows and mountain pass at the eastern r s . end of Loch Katrine, which ar e known as the T os achs 1 — During the Great War of 914 8, when large numbers of convalescent soldiers from the dominions overseas streamed through Glasgow, so great was their demand to see these famous regions, that constant parties had to be organized to conduct them over the ground. The interest of Loch Lomond and the Trossachs to the tourist of to-day is no doubt mostly due to the works 6 N LOCH LOMON D, LOCH KATRI E ’ of Sir Walter Scott . Much of the charm of Ellen s Isle and Inversnaid and the Pass of Balmaha would certainly vanish if Rob Roy and The Lady of the Lak e could be erased from our literature. -

Supporting Rural Communities in West Dunbartonshire, Stirling and Clackmannanshire

Supporting Rural Communities in West Dunbartonshire, Stirling and Clackmannanshire A Rural Development Strategy for the Forth Valley and Lomond LEADER area 2015-2020 Contents Page 1. Introduction 3 2. Area covered by FVL 8 3. Summary of the economies of the FVL area 31 4. Strategic context for the FVL LDS 34 5. Strategic Review of 2007-2013 42 6. SWOT 44 7. Link to SOAs and CPPs 49 8. Strategic Objectives 53 9. Co-operation 60 10. Community & Stakeholder Engagement 65 11. Coherence with other sources of funding 70 Appendix 1: List of datazones Appendix 2: Community owned and managed assets Appendix 3: Relevant Strategies and Research Appendix 4: List of Community Action Plans Appendix 5: Forecasting strategic projects of the communities in Loch Lomond & the Trosachs National Park Appendix 6: Key findings from mid-term review of FVL LEADER (2007-2013) Programme Appendix 7: LLTNPA Strategic Themes/Priorities Refer also to ‘Celebrating 100 Projects’ FVL LEADER 2007-2013 Brochure . 2 1. Introduction The Forth Valley and Lomond LEADER area encompasses the rural areas of Stirling, Clackmannanshire and West Dunbartonshire. The area crosses three local authority areas, two Scottish Enterprise regions, two Forestry Commission areas, two Rural Payments and Inspections Divisions, one National Park and one VisitScotland Region. An area criss-crossed with administrative boundaries, the geography crosses these boundaries, with the area stretching from the spectacular Highland mountain scenery around Crianlarich and Tyndrum, across the Highland boundary fault line, with its forests and lochs, down to the more rolling hills of the Ochils, Campsies and the Kilpatrick Hills until it meets the fringes of the urbanised central belt of Clydebank, Stirling and Alloa. -

NBG Report for KCC Meeting 21 Feb 2018 There Have Few Visible

NBG Report for KCC Meeting 21 Feb 2018 There have few visible changes in connectivity over the last month. The status of the cabinets in the various villages also remains unchanged but on the same plan as last month. Detail from last month’s Broadband Delivery Group meeting is below. For Killearn, the connectivity of premises and the status of the 2 possible further cabinets is unchanged from last month. The locations remain unknown. Premises within G63 9LA, G63 9NP, G63 9PD, G63 9PT, G63 9QG, G63 9QN, G63 9QT, G63 9QY, G63 9RQ & G63 9SQ are shown as Accepting Orders, subject to line length as to whether the service will actually be available. In Balfron no premises appear to have had upgraded connections in the past month. Balmaha premises are again unchanged this month. In Blanefield/Strathblane no premises appear to have had upgraded connections in the past month but some postcodes are now showing that the both the first cabinets (G63 9BY and G63 9JW) need to be expanded. In Buchlyvie, there are no changes this month although almost all premises are now connected. Some are acknowledged as having slower speeds than desirable. Drymen premises have not changed status this month. Croftamie premises also appear unchanged. Properties on the G63 0NH postcode, covering parts of Gartness and Balfron Station and connected to the Drymen exchange appear to be Accepting Orders although they are on very long lines and are in a future plan to use FTTP technology to deliver faster speeds. Some premises on the A811 towards Gartocharn from the A809 junction near Drymen are now showing as Accepting Orders, although some of these are on long lines and so will probably not actually get the service. -

List of Extant Applications

List of Extant Applications Week Commencing: 15 June 2020 Week Number: 24 CONTENTS Section 1 – List of applications currently pending consideration Section 2 – List of current proposal of application notices In light of the government’s controls in relation to the Coronavirus/Covid-19 pandemic, we have made changes to the way we are delivering our planning service. These measures are interim and will be updated as and when the situation changes. Please see our planning services webpage for full details (https://www.lochlomond- trossachs.org/planning/coronavirus-covid-19-planning-services/) and follow @ourlivepark for future updates. Our offices are closed to the public and staff. All staff are continuing to work from home, with restricted access to some of our systems at times. In terms of phonecalls, we would ask that you either email your case officer direct or [email protected] and we will call you back. We are not able to accept hard copy correspondence via post. Please email [email protected] LOCH LOMOND & THE TROSSACHS NATIONAL PARK AUTHORITY National Park Headquarters, Carrochan, Carrochan Road, Balloch, G83 8EG Long: 4˚34’24”W Lat: 56˚00’12”N t: 01389 722600 f: 01389 722633 e: [email protected] w: lochlomond-trossachs.org Printed on paper sourced from certified sustainable forests Page 1 of 29 Information on Applications Documents and information associated with all planning applications on this list can be viewed online at the following address: https://eplanning.lochlomond- trossachs.org/OnlinePlanning/?agree=0 -

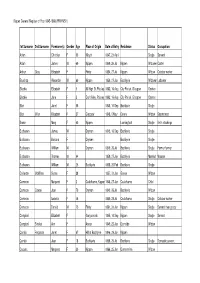

Kippen General Register of Poor 1845-1868 (PR/KN/5/1)

Kippen General Register of Poor 1845-1868 (PR/KN/5/1) 1st Surname 2nd Surname Forename(s) Gender Age Place of Origin Date of Entry Residence Status Occupation Adam Christian F 60 Kilsyth 1847, 21 April Single Servant Adam James M 69 Kippen 1849, 26 Jul Kippen Widower Carter Arthur Gray Elizabeth F Fintry 1854, 27 Jul Kippen Widow Outdoor worker Bauchop Alexander M 69 Kippen 1859, 27 Jan Buchlyvie Widower Labourer Blackie Elizabeth F 5 83 High St, Paisley 1862, 16 Aug City Parish, Glasgow Orphan Blackie Jane F 3 Croft Alley, Paisley 1862, 16 Aug City Parish, Glasgow Orphan Blair Janet F 65 1845, 16 Sep Buchlyvie Single Blair Miller Elizabeth F 37 Glasgow 1848, 6 May Denny Widow Seamstress Brown Mary F 60 Kippen Loaningfoot Single Knits stockings Buchanan James M Drymen 1845, 16 Sep Buchlyvie Single Buchanan Barbara F Drymen Buchlyvie Single Buchanan William M Drymen 1849, 26 Jul Buchlyvie Single Former farmer Buchanan Thomas M 64 1859, 27 Jan Buchlyvie Married Weaver Buchanan William M 25 Buchlyvie 1868, 20 Feb Buchlyvie Single Callander McMillan Susan F 28 1857, 31 Jan Govan Widow Cameron Margaret F 2 Cauldhame, Kippen 1848, 27 Jan Cauldhame Child Cameron Cowan Jean F 79 Drymen 1849, 26 Jul Buchlyvie Widow Cameron Isabella F 46 1859, 28 Jul Cauldhame Single Outdoor worker Cameron Donald M 75 Fintry 1861, 31 Jan Kippen Single Servant then grocer Campbell Elizabeth F Gargunnock 1845, 16 Sep Kippen Single Servant Campbell Sinclair Ann F Annan 1849, 25 Jan Darnside Widow Carrick Ferguson Janet F 67 Hill of Buchlyvie 1846, 29 Jan Kippen Carrick -

Duncan Mcneil's Presentation on the Village of Gargunnock Drawn From

Duncan McNeil’s Presentation on the Village of Gargunnock drawn from the old Statistical Accounts of 1796 & 1841 From the local history collection of John McLaren [email protected] Web Site www.gargunnockvillagehistory.co.uk Duncan McNeil’s Presentation on Gargunnock drawn from the old Statistical Accounts of 1796 & 1841 Mr McNeil’s handwritten presentation, delivered in the church hall in 1947, is held in the Stirling Council Archives at Borrowmeadow Road. It runs to 74 pages and contains an instruction at the end of line 3 on page 49 to go to an additional page 50 on which there are two paragraphs, one on the village and the other on the Rev John Stark with the further instruction to then return to the first page 50. Doing so would have resulted in the additional paragraphs being so obviously out of context that I have instead placed them in locations where they sit more comfortably within the surrounding text. They are printed in red. The photo above is of Duncan McNeil in the early 1950s. Duncan’s father Dugald worked all his life for the Stirlings of Gargunnock and Duncan, in turn, served in the same way. He and his wife lived in Shrub Cottage, Manse Brae but after his retirement moved to Hillview, Main St., Gargunnock. ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ The matter which has gone to make up this presentation tonight has been taken almost entirely from two old Statistical Accounts of the parish of Gargunnock, which I have been fortunate enough to come across some years ago. These accounts were compiled by the Parish Ministers of that time, one in 1796 almost 152 years ago by the Rev. -

ARO30: Uncovering the History and Archaeology of the House of The

ARO30: Uncovering the history and archaeology of the house of the Blackfriars, at Goosecroft Road, Stirling By Bob Will With Torben Bjarke Ballin, Beverley Ballin Smith, Ewan Campbell, Morag Cross, Gemma Cruickshanks, Richard Fawcett, Dennis Gallagher, Richard Jones, Maureen C. Kilpatrick, Dorothy McLaughlin, George MacLeod, Robin Murdoch, Susan Ramsay, Catherine Smith, Nicki J. Whitehouse Illustrated by Fiona Jackson and Gillian Sneddon Archaeology Reports Online, 52 Elderpark Workspace, 100 Elderpark Street, Glasgow, G51 3TR 0141 445 8800 | [email protected] | www.archaeologyreportsonline.com ARO30: Uncovering the history and archaeology of the house of the Blackfriars, at Goosecroft Road, Stirling Published by GUARD Archaeology Ltd, www.archaeologyreportsonline.com Editor Beverley Ballin Smith Design and desktop publishing Gillian Sneddon Produced by GUARD Archaeology Ltd 2018. ISBN: 978-0-9935632-9-4 ISSN: 2052-4064 Requests for permission to reproduce material from an ARO report should be sent to the Editor of ARO, as well as to the author, illustrator, photographer or other copyright holder. Copyright in any of the ARO Reports series rests with GUARD Archaeology Ltd and the individual authors. The maps are reproduced by permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. All rights reserved. GUARD Archaeology Licence number 100050699. The consent does not extend to copying for general distribution, advertising or promotional purposes, the creation of new collective works or resale. -

5 Forest Cottages Rowardennan Loch Lomond G63 0AW Clydeproperty.Co.Uk

5 Forest Cottages Rowardennan Loch Lomond G63 0AW To view the HD video click here clydeproperty.co.uk | page 1 clydeproperty.co.uk Enjoying an idyllic, rural setting in the Sallochy region on the eastern side of Loch Lomond, this three bedroom, semi-detached, former Forestry Commission cottage affords wonderful views over the Loch itself through the trees and the hills in the distance. Formed over two levels, the property is located at the end of a small access road and both the setting and the accommodation should ideally suit a wide demographic of buyer. This includes those wishing a holiday rental as it is situated near to the shores of Loch Lomond and right next to the West Highland Way, or to be utilised as a main residence for those wishing a more peaceful and idyllic environment or for those wishing a charming, peaceful holiday cottage, easily commutable to Glasgow, Stirling and Edinburgh. The area is a haven for those who enjoy outdoor pursuits including a number of acclaimed walking routes namely the West Highland Way itself, the infamous Ben Lomond, the Conic Hill and is also home to a number of camp sites and barbecue areas at the beautiful nearby beaches of Sallochy and Milarrochy. There are a number of local shops and services available at nearby Balmaha including a village store and the Oak Tree Inn, Pub and Restaurant and approximately five miles to the North, is the Rowardennan Hotel. Drymen offers a wider selection of shops, restaurants and services and there is schooling at Buchanan Primary School in Milton of Buchanan and Balfron High School in Balfron. -

Early History, Chapter 1 (PDF)

FROM THE WOLVES TO THE WEAVERS From the Wolves to the Weavers A tapestry of dense forest sweeps down from the volcanic fells to the south before sloping up towards the high ground of the Ibert, the place of sacrifice, where the men of the village have assembled. Ritual incantations are pierced by the frightened screams of children in the clearing in the woods below, sending the villagers scampering towards the cluster of dwellings which is their home. A scene of savage devastation meets them and the eerie silence is broken only by the ominous, satisfied howl of the wolves which have taken the village‟s children. Balfron from the Ibert (courtesy of St.Andrew‟s University Library) Of the various claims as to how Balfron was named, the story of “bail‟-a- bhroin”, the village of mourning, is probably the least credible and yet it is the accepted origin. “Town of the meeting streams” and “Town of the 1 FROM THE WOLVES TO THE WEAVERS drizzling rain”1 may be more plausible to the geographer or historian, but it is the wolf which was until the early 1990s emblazoned, incongruously enough, on the High School uniform and it is the wolf which is used by the organizations such as the Women‟s Rural Institute to symbolise their village. The simple reason why this should be the case is that, being handed down by word of mouth, it made the best story. More disquieting explanations for the acceptance of the tragic tale of the disappearing children appear in both the 13th and 17th century, as we shall discover later in this chapter. -

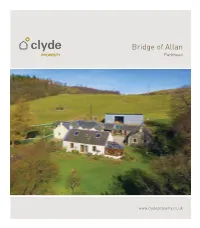

Bridge of Allan Parkhead

Bridge of Allan Parkhead www.clydeproperty.co.uk Parkhead, Bridge of Allan FK9 4LS Viewing By appointment please through Clyde Property Stirling 01786 471777 [email protected] we’re available till 8pm every day EER Rating Band E Property Ref PB8856 An absolutely charming, beautifully situated, four bedroom country home, floor is the lounge with south facing aspects and a log burning stove. sitting within the Ochil Hills Area of Great Landscape Value, and with Bedroom three is positioned on the ground floor, is double in size and is idyllic gardens offering outstanding views across Stirlingshire towards the presently used as a study. The bathroom has a four piece suite including a Gargunnock Hills with an amazing backdrop of Dumyat Hill. low level wc, wash hand basin, bath and separate shower cubicle. This is in addition to a separate wc with two piece suite. This charming country home was constructed in 1807, with later additions, and is built in stone. The roof has been finished in slate whilst double On the upper landing there are two large double bedrooms with plentiful glazed windows have been installed. Warmth is provided by oil fired central storage space in the eaves. heating. Access to the property is via a courtyard which is gravelled. Leading off The property sits within a unique location just half a mile outside Bridge of the courtyard is a car port, an external store, a double size garage, a Allan village, and adjacent to the University of Stirling’s amenity woodlands. greenhouse and a one bedroom studio apartment.