Voice in French Dubbing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revlon Signs Oscar-Nominated Actress Julianne Moore

Revlon Signs Oscar-Nominated Actress Julianne Moore November 20, 2001 NEW YORK, Nov. 20 /PRNewswire/ -- Revlon announced today that two time Oscar-nominated actress Julianne Moore has joined the company's exclusive group of spokespeople. Moore, star of the highly acclaimed films ``Hannibal,'' ``Boogie Nights'' and ``The Big Lebowski,'' will appear in advertising campaigns for the company and will participate in philanthropic efforts dedicated towards the fight against women's cancers. Moore will appear in various advertising campaigns for the Revlon brand, with the first television commercial scheduled to break nationally in January 2002. In addition, Revlon and Moore have committed to work together towards a common goal -- the fight against breast and ovarian cancers. Moore will participate in select corporate and philanthropic events for the company. ``Julianne is the perfect example of today's modern woman,'' said Revlon CEO and President Jeff Nugent. ``As a beautiful, respected actress and dedicated mother, Julianne balances her hectic schedule with grace and ease. She knows what's important in life and pursues it with confidence and integrity. We're thrilled to have such a remarkable woman representing the company,'' Nugent said. Moore most recently starred in the blockbuster hit ``Hannibal,'' opposite Anthony Hopkins and Gary Oldham. Her next role will be in the highly anticipated Miramax film, ``The Shipping News'' co-starring Kevin Spacey, Judi Dench and Cate Blanchett. The film is scheduled to be released in December 2001. ``I'm very excited to be working with a well-respected company like Revlon,'' said Julianne Moore. ``I have always admired their dedication to women's health issues and their long-standing position as a truly iconic American beauty company. -

Subtitling and Dubbing Songs in Musical Films

SUBTITLING AND DUBBING SONGS IN MUSICAL FILMS FECHA DE RECEPCIÓN: 4 de marzo FECHA DE APROBACIÓN: 17 de abril Por: Pp. 107-125. Martha García Gato Abstract Audiovisual translation (AVT) is a type of translation subjected to numerous constraints. Until now, many studies have been carried out about subtitling and dubbing in films. In musical films, which have been less studied, language transfer is mainly made through songs and, due to their characteristics, their translation is additionally constrained. This article provides some insights into some elements that make translation of songs for dubbing and subtitling a complex task using songs from the musical film My Fair Lady. Keywords Subtitling, Dubbing, Musicals, Translation, My Fair Lady. Comunicación, Cultura y Política Revista de Ciencias Sociales Subtitling and Dubbing Songs in Musical Films Resumen La traducción audiovisual (AVT) es un campo de la traducción sujeto a numerosos condicionantes. Hasta la fecha se han desarrollado múltiples estudios sobre la subtitulación y el doblaje de películas. En los musicales, menos estudiados, la transferencia lingüística recae en gran medida en las canciones y, por sus características, su traducción está sujeta a limitaciones adicionales. El presente artículo proporciona un análisis sobre algunos elementos que hacen de la traducción de las canciones para subtitular y doblar musicales una labor compleja, usando como ejemplo el musical My Fair Lady. Palabras clave Subtitulación, doblaje, musicales, traducción. 108 109 Martha García Vol.4-No.1:Enero-Junio de 2013 Introduction use of DVDs as one of the technologi- cal devises has benefited subtitling and The term ‘subtitling’ is used to refer dubbing; it is possible to watch films in to an activity which consists of adding the original version, with subtitles or printed words on a foreign film to trans- dubbed in different languages. -

'Game of Thrones,' 'Fleabag' Take Top Emmy Honors on Night of Upsets

14 TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 24, 2019 Stars hit Emmy red carpet Jodie Maisie Comer Natasha Lyonne Williams Michelle Williams Naomi Watts Sophie Turner Kendall Jenner Vera Farmiga Julia Garner beats GoT stars to win ‘Game of Thrones,’ ‘Fleabag’ take top first Emmy Los Angeles Emmy honors on night of upsets ctress Julia Gar- Los Angeles Emmy for comedy writing. Aner beat “Game of “This is just getting ridiculous!,” Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s Thrones” stars, including edieval drama “Game Waller-Bridge said as she accept- ‘Fleabag’ wins big at Emmys Sophie Turner, Lena Head- of Thrones” closed ed the comedy series Emmy. Los Angeles ey, Maisie Williams, to win Mits run with a fourth “It’s really wonderful to know, her first Emmy in Support- Emmy award for best drama se- and reassuring, that a dirty, angry, ctress Phoebe Waller-Bridge won Lead ing Actress in a Drama Se- ries while British comedy “Flea- messed-up woman can make it Actress in a Comedy Series trophy at ries category at the 2019 bag” was the upset winner for to the Emmys,” Waller-Bridge Athe 71st Primetime Emmy Awards gala Emmy awards here. best comedy series on Sunday on added. here for her role in “Fleabag”, The first-time Emmy a night that rewarded newcom- Already the most- awarded which was also named as the nominee was in contention ers over old favorites. series in best comedy series. with Gwendoline Christie Billy Porter, the star of LGBTQ The Emmys are Hollywood’s Emmy “This is just getting ridicu- (“Game of Thrones”), Head- series “Pose,” won the best dra- top honors in television, and the history lous,” Waller-Bridge said as she ey (“Game of Thrones”), matic actor Emmy, while British night belonged to Phoebe Waller- with accepted the honour for best com- Fiona Shaw (“Killing newcomer Jodie Comer took the Bridge, the star and creator of 38 wins, edy series. -

Parodic Dubbing in Spain: Digital Manifestations of Cultural Appropriation, Repurposing and Subversion 1. Introduction Having Be

The Journal of Specialised Translation Issue 32 – July 2019 Parodic dubbing in Spain: digital manifestations of cultural appropriation, repurposing and subversion Rocío Baños, University College London ABSTRACT This paper sets out to explore the phenomenon of parodic dubbing by examining its origins and situating it in its current context. Parodic dubbing symbolises the union of two loathed but highly influential forms of artistic and cultural appropriation, used innovatively in the current digital era. The aim is also to investigate how parodic dubbing reflects the politics of audiovisual translation in general, and of dubbing in particular, revealing similarities and divergences with official dubbing practices. This is done drawing on examples from two different Spanish parodic dubbings from an iconic scene from Pulp Fiction (Tarantino 1994). Throughout this work, theoretical perspectives and notions through which parodic dubbing can be examined (among others, rewriting, ideological manipulation, cultural and textual poaching, participatory culture or fandubbing) are presented, framing this phenomenon in the current discussion of fan practices and participatory culture, and drawing on theoretical perspectives and notions developed within Translation Studies and Media Studies. The investigation of the relationship between parodic dubbing, translation and subversion has illustrated that this and other forms of cultural appropriation and repurposing challenge our traditional understanding of notions such as originality, authorship and fidelity. In addition, it has revealed how such practices can be used as a site of experimentation and innovation, as well as an ideological tool. KEYWORDS Parodic dubbing, fundubbing, fandubbing, subversion, cultural appropriation. 1. Introduction Having been both praised and demonised by some scholars, intellectuals, viewers and film directors (see for instance the discussion in Yampolsky 1993 or in Nornes 2007), dubbing rarely escapes controversy. -

Moore They Live Mere Blocks Apart in Man- Inspired a Successful Off-Broadway Hattan, and Each Is the Mother of Musical

More on M 9 !"#$ %&'#(, creative director at Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia )*$+",,# -&&.#, actor, interior designer, and children’s book author 5 !" BOSTONIA Summer 2012 442-45_BostoniaSummer12_03.indd2-45_BostoniaSummer12_03.indd 4242 55/30/12/30/12 44:29:29 PMPM Moore They live mere blocks apart in Man- inspired a successful off-Broadway hattan, and each is the mother of musical. two children. They both attended After working as design direc- BU’s College of Fine Arts, and they tor for House & Garden magazine, share interests in storytelling, inte- Towey joined Martha Stewart Living rior design, and healthy cooking. in 1990 as its founding art director. ACTOR JULIANNE When Julianne Moore (CFA’83), She designed the magazine’s inau- an Academy Award–nominated gural issue, establishing its iconic MOORE TALKS actor, and Gael Towey (CFA’75), and award-winning visual style, the longtime chief creative direc- and then moved into progressively WITH FELLOW CFA tor at Martha Stewart Living Omni- larger roles at MSLO, directing the media (MSLO), first met at a CFA design of products from magazines ALUM GAEL TOWEY alumni dinner, it was clear they had and books to home furnishings and much in common—not least, their merchandise. This year she became ABOUT THE ARTS, status as highly accomplished and chief integration and creative multitalented women. director, overseeing the creation STORYTELLING, Moore, known for her intel- of digital magazines and mobile ligence, versatility, and distinctive applications for the multimillion- AND WHERE THEY red hair, has appeared in more than dollar Martha Stewart brand. 50 films, ranging from the 1998 cult The College of Fine Arts recently FIND INSPIRATION favorite The Big Lebowski to 2010’s brought Moore and Towey together critically acclaimed The Kids Are again. -

Novel to Novel to Film: from Virginia Woolf's Mrs. Dalloway to Michael

Rogers 1 Archived thesis/research paper/faculty publication from the University of North Carolina at Asheville’s NC DOCKS Institutional Repository: http://libres.uncg.edu/ir/unca/ Novel to Novel to Film: From Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway to Michael Cunningham’s and Daldry-Hare’s The Hours Senior Paper Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For a Degree Bachelor of Arts with A Major in Literature at The University of North Carolina at Asheville Fall 2015 By Jacob Rogers ____________________ Thesis Director Dr. Kirk Boyle ____________________ Thesis Advisor Dr. Lorena Russell Rogers 2 All the famous novels of the world, with their well known characters, and their famous scenes, only asked, it seemed, to be put on the films. What could be easier and simpler? The cinema fell upon its prey with immense rapacity, and to this moment largely subsists upon the body of its unfortunate victim. But the results are disastrous to both. The alliance is unnatural. Eye and brain are torn asunder ruthlessly as they try vainly to work in couples. (Woolf, “The Movies and Reality”) Although adaptation’s detractors argue that “all the directorial Scheherezades of the world cannot add up to one Dostoevsky, it does seem to be more or less acceptable to adapt Romeo and Juliet into a respected high art form, like an opera or a ballet, but not to make it into a movie. If an adaptation is perceived as ‘lowering’ a story (according to some imagined hierarchy of medium or genre), response is likely to be negative...An adaptation is a derivation that is not derivative—a work that is second without being secondary. -

Certain Women

CERTAIN WOMEN Starring Laura Dern Kristen Stewart Michelle Williams James Le Gros Jared Harris Lily Gladstone Rene Auberjonois Written, Directed, and Edited by Kelly Reichardt Produced by Neil Kopp, Vincent Savino, Anish Savjani Executive Producers Todd Haynes, Larry Fessenden, Christopher Carroll, Nathan Kelly Contact: Falco Ink CERTAIN WOMEN Cast (in order of appearance) Laura LAURA DERN Ryan JAMES Le GROS Fuller JARED HARRIS Sheriff Rowles JOHN GETZ Gina MICHELLE WILLIAMS Guthrie SARA RODIER Albert RENE AUBERJONOIS The Rancher LILY GLADSTONE Elizabeth Travis KRISTEN STEWART Production Writer / Director / Editor KELLY REICHARDT Based on stories by MAILE MELOY Producers NEIL KOPP VINCENT SAVINO ANISH SAVJANI Executive Producers TODD HAYNES LARRY FESSENDEN CHRISTOPHER CARROLL NATHAN KELLY Director of Photography CHRISTOPHER BLAUVELT Production Designer ANTHONY GASPARRO Costume Designer APRIL NAPIER Casting MARK BENNETT GAYLE KELLER Music Composer JEFF GRACE CERTAIN WOMEN Synopsis It’s the off-season in Livingston, Montana, where lawyer Laura Wells (LAURA DERN), called away from a tryst with her married lover, finds herself defending a local laborer named Fuller (JARED HARRIS). Fuller was a victim of a workplace accident, and his ongoing medical issues have led him to hire Laura to see if she can reopen his case. He’s stubborn and won’t listen to Laura’s advice – though he seems to heed it when the same counsel comes from a male colleague. Thinking he has no other option, Fuller decides to take a security guard hostage in order to get his demands met. Laura must act as intermediary and exchange herself for the hostage, trying to convince Fuller to give himself up. -

Discover Vouchers Accepted at the Ticket Desk & Candy

Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday 3 Jun 4 Jun 5 Jun 6 Jun 7 Jun 8 Jun 9 Jun 127 mins 12:00pm 10:30am 11:30am 10:15am 12:00pm 12:15pm 2:30pm 1:30pm 1:30pm 12:00pm 2:30pm 3:15pm 5:00pm 5:00pm 4:30pm 3:15pm 5:00pm 6:00pm 8:00pm 8:00pm 8:00pm 6:00pm 8:00pm 103 mins 10:15am 10:00am 2:45pm 1:30pm 113 mins 1:00pm 1:00pm 1:00pm 10:00am 1:00pm 1:00pm 3:30pm 3:30pm 1:00pm 3:30pm 3:30pm 6:00pm 6:00pm 6:00pm 3:30pm 6:00pm 6:30pm 8:30pm 8:30pm 8:30pm 6:30pm 8:30pm 149 mins 12:30pm 10:30am 10:30am 10:30am 12:30pm 12:30pm 2:00pm 12:30pm 12:30pm 12:30pm 2:00pm 3:30pm 4:30pm 4:30pm 2:30pm 3:00pm 4:30pm 5:30pm 7:30pm 7:30pm 7:30pm 6:00pm 7:30pm DISCOVER VOUCHERS 116 mins 10:15am 10:00am ALL ACCEPTED AT THE TICKET DESK TICKETS $12.50 3:15pm 3:15pm 3:15pm 3:15pm 12:00pm & CANDY BAR 6:15pm 6:15pm 6:15pm 6:30pm 6:15pm 3:00pm 134 mins ALL TICKETS 3:45pm 10:15am 10:15am 3:45pm $12.50 114 mins 12:45pm 2 x regular Movie Tickets $25 11:45am 3:45pm 3:45pm 11:45am 12:30pm 5:30pm 1 x regular Movie Ticket plus 115 mins Large or Med Combo = $25 ALL TICKETS 12:15pm 10:00am 5:30pm 1:15pm 12:15pm 6:30pm $12.50 (Not available on Special Events; 3D movies $3 extra) 108 mins 3:45pm 5:15pm 5:45pm 5:45pm 6:30pm 5:15pm 6:15pm 8:45pm 8:45pm 8:45pm 8:45pm 115 mins 10:00am 10:00am 12:45pm Sign up at the Candy 5:45pm 2:30pm 5:00pm 4:00pm 5:45pm 3:45pm Bar. -

Custom of the City Chow, Hollywood!

los angeles confidential los ® 201 5, 201 fashion springs eternal ssue 1 i CuSTom oF spring THe CiTY meeT la’S FaSHion-arTiSan a-liST CHoW, HollYWooD! inSiDe SoHo HouSe, SPaGo, CeCConi’S anD more PluS SOPHIA AMORUSO DAMIEN CHAZELLE MONIQUE LHUILLIER AUGUST GETTY julianne moore Julianne moore la-confidential-magazine.com niche media holdings, llc PUTS RED HOT IN THE RED CARPET “I’m thrilled [about the Oscar speculation]. And for a little movie that people made because they cared about it... makes you feel hope,” says Still Alice’s Oscar-nominated star Julianne Moore, here in a confection by Fendi ($9,350). 355 N. Rodeo Dr., Beverly Hills, 310-276-8888; fendi.com. 18k white-gold Juste un Clou bracelet, Cartier ($13,200). 370 N. Rodeo Dr., Beverly Hills, 310-275-4272; cartier.com. Pumps, Christian Louboutin ($945). 650 N. Robertson Blvd., West Hollywood, 310-247-9300; christian louboutin.com GODDESS ALMIGHTY BEAUTY. BRAINS… BALLS. IN STILL ALICE, JULIANNE MOORE DELIVERS YET ANOTHER HEAVENLY (READ: OSCAR-WORTHY) PERFORMANCE. BY LUKE CRISELL PHOTOGRAPHY BY KURT ISWARIENKO STYLING BY DEBORAH AFSHANI The sky is low and mercury-colored and seems to press down on New York this afternoon, crushing the holiday crowds that move shoal-like along the sidewalks. The midwinter wind is whipping down Broadway and seeping determinedly through the windows into this loud, overcrowded café, which compensates by having the radiators on overdrive: They hiss and splutter indignantly against the walls, steaming up the windows. Anyway you look at it, this is an odd place to choose for an interview. -

Cineson Productions and Film Bridge International

CineSon Productions and Film Bridge International FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ANDY GARCIA,VERA FARMIGA TO STAR IN ROMANTIC COMEDY “ADMISSIONS” Los Angeles, CA,—Andy Garcia and Vera Farmiga are set to star in indie romantic comedy “Admissions,” which Garcia will also produce through his CineSon Productions. Adam Rodgers will direct from a script co-written with Glenn German, who will also produce alongside Sig Libowitz, under his Look at the Moon Productions banner. Ellen Wander of Film Bridge International will executive produce along with Sonya Lunsford (Academy Award-winning box office hit “The Help”), with Wander and FBI handling international distribution. “Admissions” centers on a once-in-a-lifetime relationship that develops between two strangers over the course of a single day. Farmiga portrays Edith, a free-spirited mom taking her driven daughter Audrey on a walking tour of a beautiful small college. Garcia plays buttoned-up heart surgeon George, who’s taking his son Conrad on the same tour. Failing comically to connect with their respective children, George and Edith decide to play “tour hooky” together for the rest of the afternoon. The result is a surprising romance and the greatest half-day of their lives. Academy Award nominee Farmiga (“Up In The Air,” “The Departed,” “Higher Ground,” “Safe House”) has recently wrapped New Line Cinema’s “The Warren Files.” Academy Award nominee Garcia (“The Godfather: Part III”, “The Untouchables”, “Ocean’s 11”) toplines two soon-to-be released films—“For Greater Glory” and “The Truth.” Rodgers’ most recent film as director, “The Response,” was short-listed for the 2010 Academy Awards as Best Live Action Short Film. -

Press-Release-The-Endings.Pdf

Publication Date: September 4, 2018 Media Contact: Diane Levinson, Publicity [email protected] 212.354.8840 x248 The Endings Photographic Stories of Love, Loss, Heartbreak, and Beginning Again By Caitlin Cronenberg and Jessica Ennis • Foreword by Mary Harron 11 x 8 in, 136pp, Hardcover, Photographs throughout ISBN 978‐1‐4521‐5568‐5, $29.95 Featuring some of today’s most celebrated actresses, including Julianne Moore, Alison Pill, and Imogen Poots, the photographic vignettes in The Endings capture female characters in the throes of emotional transformation. Photographer Caitlin Cronenberg and art director Jessica Ennis created stories of heartbreak, relationship endings, and new beginnings—fictional but often inspired by real life—and set out to convey the raw emotions that are exposed in these most vulnerable states. Cronenberg and Ennis collaborated with each actress to develop a character, build the world she inhabits, and then photograph her as she lived the role before the camera. Patricia Clarkson depicts a woman meeting her younger lover in the campus library—even though they both know the relationship has been over since before it even began. Juno Temple portrays a broken‐hearted woman who engages in reckless and self‐destructive behavior to numb the sadness she feels. Keira Knightley ritualistically cleanses herself and her home after the death of her great love. Also featured are Jennifer Jason Leigh, Danielle Brooks, Tessa Thompson, Noomi Rapace, and many more. These intimate images combine the lush beauty and rich details of fashion photographs with the drama and narrative energy of film stills. Telling stories of sadness, loneliness, anger, relief, rebirth, freedom, and happiness, they are about relationship endings, but they are also about beginnings. -

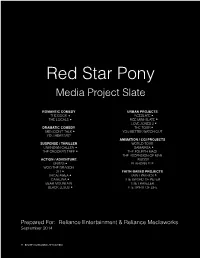

Project Slate

Red Star Pony Media Project Slate ROMANTIC COMEDY! URBAN PROJECTS! THE BOOK RCESLATE THE LOCALS RCE MINI-SLATE ! LOVE JONES 2 DRAMATIC COMEDY! THE TOUR MEN DON’T TALK YOU BETTER WATCH OUT YOU HEAR ME? ! ! ANIMATION / CGI PROJECTS! SUSPENSE / THRILLER! WORLD TOUR UNKNOWN CALLER SAMAIREA THE CROOKED TREE THE FOURTH MAGI ! THE ASCENSION OF MAN ACTION / ADVENTURE! BUDDY UNITAS ELKHORN ELF WOO THE DRAGON ! 311 FAITH-BASED PROJECTS! SACAJAWEA SAINT PATRICK CATALINA THE SWORD OF PETER BEAR MOUNTAIN THE TRAVELER BLACK JESUS THE SPIRIT OF LIFE ! ! ! Prepared For: Reliance Entertainment & Reliance Mediaworks September 2014 BRIEF OVERVIEW ATTACHED THE LOCALS MAJOR MOTION PICTURE Media Type: Major Motion Picture Genre: Romantic Comedy MPAA Rating: PG-13 (anticipated) Logline: The Locals is a comedic love story set in the Bronx about two three-generational families who are set in their ways: the Goldberg’s and the Romano’s. Their perspectives on life are challenged as love, and illness, strikes both families. The Locals is a modern day Moonstruck meets Little Miss Sunshine. Production Budget: $6.4M The Locals Location: New York (25% tax incentive, estimated) Financing: $3M equity; 100% gross receipts until 115% recoupment; 50% gross receipts thereafter Producers: Sue Kramer, Jill Footlick, James Sinclair Writer: Sue Kramer Director: Sue Kramer (Gray Matters, The God of Driving) Distribution: TBD (domestic); IM Global * (international) Cast: TBD * ! ! ! ! ! Shirley MacLaine Alan Arkin Vera Farmiga Richard Schiff Annabella Sciorra Alfred Molina Odeya