Recordtv Pte Ltd V Mediacorp TV Singapore Pte Ltd and Others

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PAY-TV CONSOLIDATION to ACCELERATE in APAC Daily Website Update • Bi-Monthly Magazine • Searchable Archive

MCI (P) 047/06/2017 PPS 1812/01/2013 (025534) ISSN 0219-6166 www.onscreenasia.com Vol. 26 | Issue 02 | April-May 2019 PAY-TV CONSOLIDATION TO ACCELERATE IN APAC Daily website update • Bi-monthly Magazine • Searchable archive TELEVISION ASIA HAS BEEN AQUIRED BY HARVEST INFORMATIONwww.tva.onscreenasia.com For advertising opportunities, please contact: K. Dass at Tel: (65) 68289333 | email: [email protected] editor’snote PUBLISHING K.DASS Collaboration & acquisition EDITORIAL DIRECTOR/PUBLISHER [email protected] paves the way of future video (65) 6828 9333 streaming EDITORIAL YI AN ANG I hear of economic doldrums that have set the stage EDITORIAL ASSISTANT smaller until more doors are open for opportunities in the market. But remember, the show must go [email protected] on and we are the drivers. APOS, the C-Suite (65) 6828 9333 conference in Bali this month ensures promising breakthroughs for telcos, broadcasters, operators, ANG LER SING producers and investors as they discuss, assist and EDITORIAL ASSISTANT collaborate in many a times. [email protected] (65) 6828 9333 Setting the stage right and creating opportunities for many is Netflix. The streaming champion ALISON YEO recently announced a new slate of ten original Indian K. Dass, Editorial Director films, taking to 15 the number of Indian movies set EDITORIAL ASSISTANT to be available on the streaming service globally by the end of 2020. Given [email protected] the diversity, history and culture, India is home to powerful stories waiting (65) 6828 9333 to be told to audiences around the world. The depth of talent and vision of its creators is enabling Netflix to create films viewers will fall in love. -

New Horizons in Broadcasting

Conference Proceedings 14TH International Conference & Exhibition on Terrestrial and Satellite Broadcasting Theme : New Horizons in Broadcasting 23rd, 24th and 25th February, 2008 Venue : Hall No. 12, Pragati Maidan, New Delhi (India) Organised By Broadcast Engineering Society (India) 912, Surya Kiran Building, 19 Kasturba Gandhi Marg, New Delhi-110001, India Tel.: +91-11-43520895, 43520896 Fax : +91-11-43520897 E-mail : [email protected] Website : besindia.com Theme: New Horizons in Broadcasting Conference Programme Venue: Pragati Maidan, New Delhi 23RD FEBRUARY 2008 Inauguration Shri. Priya Ranjan Dasmunsi Keynote Speaker Dr. Kazuyoshi Shogen, (1000 hrs) Hon'ble Minister for Information & Broadcasting & Executive Research Engineer, NHK, Japan Parliamentary Affairs, Govt. of India High Tea 1130 Hrs. Guests of Honor Smt. Asha Swaroop Tutorial HDTV Secretary, Ministry of Information & Broadcasting, Govt. of India (1430 - 1600 hrs) Mr. Hiduki Ohtaka Shri. B.S.Lalli, Chief Executive Officer, Prasar Bharati, India Chief Engineer, Panasonic, Japan 24TH FEBRUARY 2008 25TH FEBRUARY 2008 Session – I DTT in the age of Cable and DTH Session – V Digital Radio-New Experiences (0930 - 1100 hrs) Session Chairman - Mr. N.P. Nawani, Secretary General (0930 - 1100 hrs) Session Chairman - Mr. H.R. Singh Indian Broadcasting Foundation (IBF), New Delhi Engineer-in-Chief, All India Radio, India Speakers Speakers 1. Mr. Azzedine Boubguira, DiBcom, France 1. Mr. Peter Senger, Chairman & Director, DRM, Deutsche Welle Market impact of diversity implementation on mobile and Digital Radio Mondiale – New Experience Portable TV receivers 2. Mr. David Birrer, Thomson Broadcast & Multimedia AG, France 2. Mr. L.V. Sharma, Doordarshan, India Innovations in AM Broadcasting DTT – Opportunities and Challenges 3. -

A PROGRAMAÇÃO EM TEMPOS DE UBIQUIDADE TELEVISIVA: Um Estudo Direcionado Ao Plano De Distribuição De Conteúdos Da TV UNESP

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL PAULISTA “JÚLIO DE MESQUITA FILHO” FACULDADE DE ARQUITETURA, ARTES E COMUNICAÇÃO FERNANDO ARAÚJO VELLOSA A PROGRAMAÇÃO EM TEMPOS DE UBIQUIDADE TELEVISIVA: um estudo direcionado ao plano de distribuição de conteúdos da TV UNESP Bauru – SP 2017 FERNANDO ARAÚJO VELLOSA A PROGRAMAÇÃO EM TEMPOS DE UBIQUIDADE TELEVISIVA: um estudo direcionado ao plano de distribuição de conteúdos da TV UNESP FERNANDO ARAÚJO VELLOSA RA 131031635 Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso apresentado como exigência para obtenção do título de Bacharel em Comunicação Social: Radialismo apresentado à Faculdade de Arquitetura, Artes e Comunicação da Universidade Estadual Paulista “Júlio de Mesquita Filho”, sob orientação da Profa. Adj. Ana Silvia Lopes Davi Médola. Bauru – SP 2017 FERNANDO ARAÚJO VELLOSA A PROGRAMAÇÃO EM TEMPOS DE UBIQUIDADE TELEVISIVA: um estudo direcionado ao plano de distribuição de conteúdos da TV UNESP Banca examinadora: _____________________________________________ Profa. Adj. Ana Sílvia Lopes Davi Médola Universidade Estadual Paulista _____________________________________________ Profa. Dra. Tamara de Souza Brandão Guaraldo Universidade Estadual Paulista _____________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Willians Cerozzi Balan Universidade Estadual Paulista Resultado: _____________________________________________ Bauru, 7 de março de 2017. AGRADECIMENTOS Aos meus pais, pelo apoio em todos os momentos; Aos amigos Henrique Pereira e Muriel Vieira pelo suporte durante este processo e pelas nossas discussões sobre o universo da televisão; Aos colegas de graduação, em especial aos amigos Ana Stamato, Betânia Menardi, Carol Molina, Maicon Milanezi, Mariana Carrion, Thalita Bianchini e Vinícius Laureto; Aos membros integrantes do GEA, Aline Ap. Santos, Bruno Jareta, Carlos Sabino, Elissa Schpallir, Jaqueline Schiavoni, Mariane Lelis, Natália Coquemala, Octávio Neto e Thiago T.J.; Aos professores, funcionários e estagiários da TV UNESP pelos ensinamentos acerca da prática televisiva no contexto universitário. -

PRISM Architecture: Supporting Enhanced Streaming Services in a Content Distribution Network

1 PRISM Architecture: Supporting Enhanced Streaming Services in a Content Distribution Network C. D. Cranor, M. Green, C. Kalmanek, D. Shur, S. Sibal, C. Sreenan and J.E. van der Merwe ¡ AT&T Labs - Research ¢ University College Cork Florham Park, NJ, USA Cork, Ireland Abstract IP content distribution networks (CDNs) provide scal- PRISM is an architecture for distributing, storing, and ability by distributing many servers across the Internet delivering high quality streaming content over IP networks. “close” to consumers. Consumers obtain content from In this paper we present the design of the PRISM architec- these edge servers directly rather than from the origin ture and show how it can support an enhanced set of stream- server. Current CDNs support traditional Web content ing services. In particular, PRISM supports the distribu- fairly well, however support for streaming content is typ- tion and delivery of live television content over IP, as well ically less sophisticated and often limited to the deliv- as the storage of such content for subsequent on-demand ery of fairly low quality live streams (so called “web- access. In addition to accommodating the unique aspects casting”) and distribution of low-to-medium quality video of these types of services, PRISM also offers the frame- clips (“clip-acceleration”). In order for Internet-based work and architectural components necessary to support streaming to approach the same level of entertainment other streaming content distribution networks (CDN) ser- value as broadcast media, CDNs must drastically improve vices such as video-on-demand. We present an overview the quality of streaming that can be supported. -

Universidade Federal De Juiz De Fora Faculdade De Comunicação Social Mestrado Em Comunicação

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE JUIZ DE FORA FACULDADE DE COMUNICAÇÃO SOCIAL MESTRADO EM COMUNICAÇÃO Pedro Augusto Silva Miranda INTIMIDADE MEDIADA: as estratégias narrativas do GloboNews Em Pauta na comunicação com o público Juiz de Fora 2019 Pedro Augusto Silva Miranda INTIMIDADE MEDIADA: as estratégias narrativas do GloboNews Em Pauta na comunicação com o público Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- graduação em Comunicação, da Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora como requisito parcial a obtenção do grau de Mestre em Comunicação. Área de concentração: Comunicação e Sociedade. Orientadora: Prof.a Dra. Cláudia de Albuquerque Thomé Juiz de Fora 2019 Ficha catalográfica elaborada através do programa de geração automática da Biblioteca Universitária da UFJF, com os dados fornecidos pelo(a) autor(a) Miranda, Pedro Augusto Silva. Intimidade Mediada : as estratégias narrativas do GloboNews Em Pauta na comunicação com o público / Pedro Augusto Silva Miranda. -- 2019. 173 p. Orientadora: Cláudia de Albuquerque Thomé Dissertação (mestrado acadêmico) - Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora, Faculdade de Comunicação Social. Programa de Pós Graduação em Comunicação, 2019. 1. Narrativas. 2. Estratégias. 3. TV por assinatura. 4. Telejornalismo. 5. GloboNews Em Pauta. I. Thomé, Cláudia de Albuquerque, orient. II. Título. Dedico este trabalho aos meus pais, Xavier e Maria, e ao meu irmão Junior. Exemplos de coragem, dedicação e amor incondicional. AGRADECIMENTOS Agradeço, primeiramente, a Deus, por permitir que esse momento acontecesse e por ser luz em meio às adversidades dessa caminhada. Obrigado por me fazer acreditar e mostrar que todos os meus sonhos são possíveis. Agradeço a minha família, pai, mãe e irmão, por sempre estarem ao meu lado com muito amor e acreditando em mim e que tudo daria certo. -

OPPORTUNITY LOST? Revisiting Recordtv V Mediacorptv*

16 Singapore Academy of Law Journal (2012) 24 SAcLJ OPPORTUNITY LOST? Revisiting RecordTV v MediaCorpTV* Taking the Singapore Court of Appeal’s Decision in RecordTV Pte Ltd v MediaCorp TV Singapore Pte Ltd [2011] 1 SLR 830, this article seeks to argue that the copyright fair dealing defence would have been the more appropriate basis to exempt RecordTV, a digital recording service for recording television programmes, from primary copyright liability. This judicial approach towards legalising digital video recorder (“DVR”) services is more suitable taking into consideration the following: The role and objectives of copyright law in Singapore; the history and development of the fair dealing defence (including the latest amendments pursuant to the US-Singapore Free Trade Agreement); the global trends relating to user rights and information technology through a comparative study of similar cases in other jurisdictions; and a policy assessment of Singapore’s interests in promoting innovation and development against the backdrop of proprietary copyright protection. Warren B CHIK LLB (Hons) (National University of Singapore), LLM (Tulane) (UCL); Advocate and Solicitor (Singapore); Assistant Professor, School of Law, Singapore Management University. SAW Cheng Lim LLB (Hons) (National University of Singapore), LLM (Cambridge); Advocate and Solicitor (Singapore); Associate Professor, School of Law, Singapore Management University. * This study was funded through a research grant (Project Fund No 11-C234-SMU-001) from the Office of Research, Singapore Management University. The study includes an earlier analysis of the case by the joint authors: Saw Cheng Lim & Warren Chik, “Where Copyright Law and Technology Once Again Cross Paths – The Continuing Saga: RecordTV Pte Ltd v MediaCorp TV Singapore Pte Ltd [2011] 1 SLR 830” (2011) 23 SAcLJ 653. -

A History of Age-Rating Television in Brazil

International Journal of Communication 13(2019), 1167–1185 1932–8036/20190005 The Children Are Watching: A History of Age-Rating Television in Brazil LIAM GREALY1 CATHERINE DRISCOLL The University of Sydney, Australia ANDREA LIMBERTO The National Service for Commercial Education and University of São Paulo, Brazil Histories of Brazilian media regulation typically emphasize a major transformation with the passing of the federal constitution in 1988, contrasting censorship during the military period of 1964‒1985 with age rating, or “indicative classification,” thereafter. Contemporary conflicts among child advocates, television broadcasters, and the state as monitor of the industry’s self-regulation are grounded in a much longer history of age rating in popular media. Drawing on an examination of files from Brazil’s Ministry of Justice and interviews with current examiners, this article provides a history of age ratings for television in Brazil and of the processes by which classification decisions are made. We argue that the desire to limit young people’s access to television through age ratings has had significant ramifications in Brazil, evident in the formation of legal regimes, reform of institutional practices, and even the revision of time zones. Keywords: media classification, age rating, youth, minority, time zones, legal reform, Brazilian television, telenovelas The passing of Brazil’s federal constitution in 1988 was a central achievement in the nation’s transition from a prolonged era of military government to renewed democracy. Regarding media regulation, the constitution is usually understood as a shift from state-led censorship characterized by inconsistency, opaque decision making, and restrictions on political criticism to protected freedom of expression with media subjected to a system of differentiated age-based classifications. -

323968002009.Pdf

La Trama de la Comunicación ISSN: 1668-5628 ISSN: 2314-2634 [email protected] Universidad Nacional de Rosario Argentina Cavalcanti Versiani dos Anjos, Júlia Vítimas do bisturi. Mídia, gênero e a ponta afiada da biopolítica La Trama de la Comunicación, vol. 25, núm. 1, 2021, -Junio, pp. 143-158 Universidad Nacional de Rosario Rosario, Argentina Disponible en: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=323968002009 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Redalyc Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina y el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Vítimas do bisturi Mídia, gênero e a ponta afiada da biopolítica Por Júlia dos Anjos [email protected] - Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro SUMARIO: SUMMARY: La cirugía plástica es una práctica generalizada mundialmen- Plastic surgery is a widespread practice worldwide and, te y, en especial, entre el público femenino brasileño, lo que especially, among brazilian women, which has led Brazil to ha convertido Brasil en el líder del ranking mundial de inter- lead the global ranking of interventions. The intense affini- venciones. La intensa afinidad entre los medios de comuni- ty between medical knowledge and the media is one of the cación y el conocimiento médico es uno de los factores que factors that contribute to the trivialization of these practices, contribuyen a la trivialización de estas prácticas, olvidando obliterating the existing risks. In order to investigate the con- los riesgos existentes. Para investigar las consecuencias sequences of the articulation between press, biopolitics and de la articulación entre prensa, biopolítica y género, este gender, this paper analyses the media coverage on the death trabajo analiza la cobertura mediática de la muerte de una of a woman after an aesthetic procedure. -

NMS ETA Stereo

Digital TV HD Set-top Box STB2-T2 NMS ETATM Stereo Advanced Digital TV Set-top Box User Guide English CONTENTS Safety Information ........................................................................................... 3 Introduction ..................................................................................................... 4 Set-top Box Front Panel ................................................................................. 4 Set-top Box Back Panel ................................................................................. 4 Remote Control .............................................................................................. 5 Setting up for Standard Definition Television Set ............................................ 6 Setting up for High Definition Television Set ................................................... 6 Menu ................................................................................................................ 7 Menu → Media Player .................................................................................... 7 Menu → Edit Channel .................................................................................... 8 Menu → Installation ........................................................................................ 8 Menu → System Setup .................................................................................. 9 Menu → System Setup ................................................................................ 10 Menu → Miscellaneous ............................................................................... -

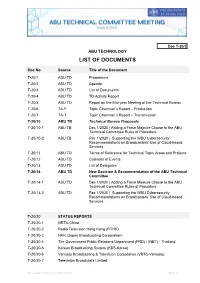

List of Documents

Doc T-20/3 ABU TECHNOLOGY LIST OF DOCUMENTS Doc No Source Title of the Document T-20/1 ABU TD Programme T-20/2 ABU TD Agenda T-20/3 ABU TD List of Documents T-20/4 ABU TD TD Activity Report T-20/5 ABU TD Report on the Mid-year Meeting of the Technical Bureau T-20/6 TA-P Topic Chairman’s Report – Production T-20/7 TA-T Topic Chairman’s Report – Transmission T-20/10 ABU TB Technical Bureau Proposals T-20/10-1 ABU TB Dec 1/2020 | Adding a Force Majeure Clause to the ABU Technical Committee Rules of Procedure T-20/10-2 ABU TB Rec 1/2020 | Supporting the WBU Cybersecurity Recommendations on Broadcasters’ Use of Cloud-based Services T-20/11 ABU TD Terms of Reference for Technical Topic Areas and Projects T-20/12 ABU TD Calendar of Events T-20/13 ABU TD List of Delegates T-20/14 ABU TD New Decision & Recommendation of the ABU TechnicAl Committee T-20/14-1 ABU TD Dec 1/2020 | Adding a Force Majeure Clause to the ABU Technical Committee Rules of Procedure T-20/14-2 ABU TD Rec 1/2020 | Supporting the WBU Cybersecurity Recommendations on Broadcasters’ Use of Cloud-based Services T-20/20 STATUS REPORTS T-20/20-1 NRTA-China T-20/20-2 Radio Television Hong Kong (RTHK) T-20/20-3 NHK (Japan Broadcasting Corporation) T-20/20-4 The Government Public Relations Department (PRD) / (NBT) - Thailand T-20/20-5 Korean Broadcasting System (KBS-Korea) T-20/20-6 Vanuatu Broadcasting & Television Corporation (VBTC-Vanuatu) T-20/20-7 Television Broadcasts Limited Document T-20/3 List of Documents Page 1 Doc No Source Title of the Document T-20/20-8 Vietnam Television -

Hybridity in Singaporean Cinema: Othering the Self Through Diaspora and Language Policies in Ilo Ilo and Letters from the South

FM4204: Time, Space and the Visceral in South East Asian Cinema Hybridity in Singaporean Cinema: Othering the Self through Diaspora and Language Policies in Ilo Ilo and Letters from the South Student Name: Amanda Curdt-Christiansen Matriculation Number: 140008304 Module Tutor: Dr Philippa Lovatt Date: 21/05/18 Word Count: 3849 FM4204 140008304 爸妈不在家/Ilo Ilo is a Singaporean film directed by Anthony Chen and released in 2013. It recounts the unanticipated development of a relationship between a Filipina woman, Teresa, and a Chinese-Singaporean boy, Jiale, whom she is employed to look after. The story unfurls against the backdrop of the Asian financial crisis of 1997, showcasing the struggle of a very young country in maintaining its core values, its independence, and its dignity in the face of economic disaster. 南方来信/Letters from the South is comprised of six short films from Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand and Myanmar, released in 2013. Of these, I will be focusing on Sun Koh’s film, Singapore Panda, which examines tensions between national and cultural identity in the Chinese diaspora in Singapore. This essay will aim to explicate how diasporic communities maintain (or fail to maintain) their cultural identity in Singaporean cinema. Using Ilo Ilo and Singapore Panda as a starting point, I will unpack how divergent cultural backgrounds colour the style of popular Singaporean films, particularly in their treatment of space. I will begin by providing a contextualisation of the films in terms of the Singaporean political climate: language policy, post-colonial policy, and how these contribute to conflict between the nation and the self. -

Processo: 0601969-65.2018.6.00.0000

Tribunal Superior Eleitoral PJe - Processo Judicial Eletrônico 09/12/2018 Número: 0601969-65.2018.6.00.0000 Classe: AÇÃO DE INVESTIGAÇÃO JUDICIAL ELEITORAL Órgão julgador colegiado: Colegiado do Tribunal Superior Eleitoral Órgão julgador: Corregedor Geral Eleitoral Ministro Jorge Mussi Última distribuição : 09/12/2018 Valor da causa: R$ 0,00 Assuntos: Abuso - Uso Indevido de Meio de Comunicação Social Segredo de justiça? NÃO Justiça gratuita? NÃO Pedido de liminar ou antecipação de tutela? NÃO Partes Procurador/Terceiro vinculado PARTIDO DOS TRABALHADORES (PT) - NACIONAL CAROLINA FREIRE NASCIMENTO (ADVOGADO) (AUTOR) GABRIEL BRANDAO RIBEIRO (ADVOGADO) RACHEL LUZARDO DE ARAGAO (ADVOGADO) MIGUEL FILIPI PIMENTEL NOVAES (ADVOGADO) ANGELO LONGO FERRARO (ADVOGADO) EUGENIO JOSE GUILHERME DE ARAGAO (ADVOGADO) MARCELO WINCH SCHMIDT (ADVOGADO) JAIR MESSIAS BOLSONARO (RÉU) ANTONIO HAMILTON MARTINS MOURAO (RÉU) EDIR MACEDO BEZERRA (RÉU) DOUGLAS TAVOLARO DE OLIVEIRA (RÉU) MARCIO PEREIRA DOS SANTOS (RÉU) THIAGO ANTUNES CONTREIRA (RÉU) DOMINGOS FRAGA FILHO (RÉU) Procurador Geral Eleitoral (FISCAL DA LEI) Documentos Id. Data da Documento Tipo Assinatura 29409 09/12/2018 23:55 Petição Inicial Petição Inicial 38 29417 09/12/2018 23:55 AIJE - RECORD - Uso indevido dos meios de Petição Inicial Anexa 88 comunicação 29409 09/12/2018 23:55 Anexo 1 - Edir Macedo declara apoio a Bolsonaro - Documento de Comprovação 88 Política - Estadão 29410 09/12/2018 23:55 Anexo 2 - Bispo Edir Macedo diz no Facebook que Documento de Comprovação 38 apoia Bolsonaro _ VEJA.com