“The Ten-Year Plan” (1993) and “Bygones”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Press Release Is Not an Offer to Sell Or a Solicitation of Any Offer to Buy the Securities of Kenedix Realty Investment

Translation of Japanese Original July 5, 2011 To All Concerned Parties REIT Issuer: Kenedix Realty Investment Corporation 2-2-9 Shimbashi, Minato-ku, Tokyo Taisuke Miyajima, Executive Director (Securities Code: 8972) Asset Management Company: Kenedix REIT Management, Inc. Taisuke Miyajima, CEO and President Inquiries: Masahiko Tajima Director / General Manager, Financial Planning Division TEL.: +81-3-3519-3491 Notice Concerning Acquisitions of Properties (Conclusion of Agreements) (Total of 4 Office Buildings) Kenedix Realty Investment Corporation (“the Investment Corporation”) announced its decision on July 5, 2011 to conclude agreements to acquire 4 office buildings. Details are provided as follows. 1. Outline of the Acquisition (1) Type of Acquisition : Trust beneficiary interests in real estate (total of 4 office buildings) (2) Property Name and : Details are provided in the chart below. Planned Acquisition Price Anticipated Acquisition Price Property No. Property Name (In millions of yen) A-71 Kyodo Building (Iidabashi) 4,670 A-72 P’s Higashi-Shinagawa Building 4,590 A-73 Nihonbashi Dai-2 Building 2,710 A-74 Kyodo Building (Shin-Nihonbashi) 2,300 Total of 4 Office Buildings 14,270 *Excluding acquisition costs, property tax, city-planning tax, and consumption tax, etc. Each aforementioned building shall hereafter be referred to as “the Property” or collectively, “the Four Properties.” (3) Seller : Please refer to Item 4. “Seller’s Profile” for details. The following (4) through (9) applies for each of the Four Properties. This press release is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of any offer to buy the securities of Kenedix Realty Investment Corporation in the United States or elsewhere. -

Und Audiovisuellen Archive As

International Association of Sound and Audiovisual Archives Internationale Vereinigung der Schall- und audiovisuellen Archive Association Internationale d'Archives Sonores et Audiovisuelles (I,_ '._ • e e_ • D iasa journal • Journal of the International Association of Sound and Audiovisual Archives IASA • Organie de I' Association Internationale d'Archives Sonores et Audiovisuelle IASA • Zeitschchrift der Internationalen Vereinigung der Schall- und Audiovisuellen Archive IASA Editor: Chris Clark,The British Library National Sound Archive, 96 Euston Road, London NW I 2DB, UK. Fax 44 (0)20 7412 7413, e-mail [email protected] The IASA Journal is published twice a year and is sent to all members of IASA. Applications for membership of IASA should be sent to the Secretary General (see list of officers below). The annual dues are 25GBP for individual members and IOOGBP for institutional members. Back copies of the IASA Journal from 1971 are available on application. Subscriptions to the current year's issues of the IASA Journal are also available to non-members at a cost of 35GBP I 57Euros. Le IASA Journal est publie deux fois I'an etdistribue a tous les membres. Veuillez envoyer vos demandes d'adhesion au secretaire dont vous trouverez I'adresse ci-dessous. Les cotisations annuelles sont en ce moment de 25GBP pour les membres individuels et 100GBP pour les membres institutionels. Les numeros precedentes (a partir de 1971) du IASA Journal sont disponibles sur demande. Ceux qui ne sont pas membres de I'Association peuvent obtenir un abonnement du IASA Journal pour I'annee courante au coOt de 35GBP I 57 Euro. -

Kagurazaka Campus 1-3 Kagurazaka,Shinjuku-Ku,Tokyo 162-8601

Tokyo University of Science Kagurazaka Campus 1-3 Kagurazaka,Shinjuku-ku,Tokyo 162-8601 Located 3 minutes’ walk from Iidabashi Station, accessible via the JR Sobu Line, the Tokyo Metro Yurakuchom, Tozai and Namboku Lines, and the Oedo Line. ACCESS MAP Nagareyama- Unga Otakanomori Omiya Kasukabe Noda Campus 2641 Yamazaki, Noda-shi, Chiba Prefecture 278-8510 Kanamachi Kita-Senju Akabane Tabata Keisei-Kanamachi Ikebukuro Nishi- Keisei-Takasago Nippori Katsushika Campus 6-3-1 Niijuku, Katsushika-ku, Nippori Oshiage Tokyo 125-8585 Asakusa Ueno Iidabashi Ochanomizu Shinjuku Kinshicho Akihabara Asakusabashi Kagurazaka Campus Kanda 1-3 Kagurazaka, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 162-8601 Tokyo ■ From Narita Airport Take the JR Narita Express train to Tokyo Station. Transfer to the JR Yamanote Line / Keihin-Tohoku Line and take it to Akihabara Station. Transfer to the JR Sobu Line and take it to Iidabashi Station. Travel time: about 1 hour 30 minutes. ■ From Haneda Airport Take the Tokyo Monorail Line to Hamamatsucho Station. Transfer to the JR Yamanote Line / Keihin-Tohoku Line and take it to Akihabara Station. Transfer to the JR Sobu Line and take it to Iidabashi Station. Travel time: about 45 minutes. ■ From Tokyo Station Take the JR Chuo Line to Ochanomizu Station. Transfer to the JR Sobu Line and take it to Iidabashi Station. Travel time: about 10 minutes. ■ From Shinjuku Station Take the JR Sobu Line to Iidabashi Station. Travel time: about 12 minutes. Building No.10 Building No.11 Annex Building No.10 Building No.5 CAMPUS MAP Annex Kagurazaka Buildings For Ichigaya Sta. Building No.11 Building No.12 Building No.1 1 Building No.6 Building No.8 Building Building No.13 Building Building (Morito Memorial Hall) No.7 No.2 No.3 3 1 The Museum of Science, TUS (Futamura Memorial Hall) & Building Mathematical Experience Plaza No.9 2 2 Futaba Building (First floor: Center for University Entrance Examinations) Tokyo Metro Iidabashi Sta. -

The Port Weekly SUPPORT

REPORT CARDS SUPPORT NEXT WEEK The Port Weekly RED CROSS VoL XVI—No. 7 SENIOR fflGH SCHOOL. PORT WASHINGTON. LONG ISLAND. N. Y.. FRIDAY. DECEMBER I. 1939 Price: Five CsntB Teachers Heeling 4 Committee Named Second Annual Fall Convention Discusses Port To Investigate Of Nassau County Press Group Narking System Handbook To Be Held At Adelphi College Definite Meaning Is Given G. O. Is Planning To Publish Many Well Known Newspapermen Will Speak On Wednesday, To Various Graduations Handbook For Newcomers December 6; Panel Discussion And Criticism Of Newspapers Of H. S. U About Port High School To Be Held; Banquet And Press Dance Will Close Confab The Second Annual Fall Con- A t the teachers meeting of last A t the November 21 meeting vention of the Nassau County Tuesday, which mii in rtyjm 108, of the student council a coi.iin.t- Midc h Popular Press Association will be held the present system of marking tee of three was appointed to during the afternoon and evening was discussed. The meanings of look into the possibilities of pub- m CHRISTMAS SEALS lishing a student handbook. This Noontime Activity of December 6 at Adelphi College each grade were again defined to handbook would contain informa- i n Garden City. provide for greater uniformity in tion about school in general and North Shore Symphony Plans All Nassau school newspaper the marking procedure. Fall Play To Be its extracurricular activities that To Present Concert staffs are invited to attend this I n Subject Mastery should be of interest to students convention. Christian Burckel, entering this school. -

A Piece of History

A Piece of History Theirs is one of the most distinctive and recognizable sounds in the music industry. The four-part harmonies and upbeat songs of The Oak Ridge Boys have spawned dozens of Country hits and a Number One Pop smash, earned them Grammy, Dove, CMA, and ACM awards and garnered a host of other industry and fan accolades. Every time they step before an audience, the Oaks bring four decades of charted singles, and 50 years of tradition, to a stage show widely acknowledged as among the most exciting anywhere. And each remains as enthusiastic about the process as they have ever been. “When I go on stage, I get the same feeling I had the first time I sang with The Oak Ridge Boys,” says lead singer Duane Allen. “This is the only job I've ever wanted to have.” “Like everyone else in the group,” adds bass singer extraordinaire, Richard Sterban, “I was a fan of the Oaks before I became a member. I’m still a fan of the group today. Being in The Oak Ridge Boys is the fulfillment of a lifelong dream.” The two, along with tenor Joe Bonsall and baritone William Lee Golden, comprise one of Country's truly legendary acts. Their string of hits includes the Country-Pop chart-topper Elvira, as well as Bobbie Sue, Dream On, Thank God For Kids, American Made, I Guess It Never Hurts To Hurt Sometimes, Fancy Free, Gonna Take A Lot Of River and many others. In 2009, they covered a White Stripes song, receiving accolades from Rock reviewers. -

Kagurazaka Campus 1-3 Kagurazaka,Shinjuku-Ku,Tokyo 162-8601

Tokyo University of Science Kagurazaka Campus 1-3 Kagurazaka,Shinjuku-ku,Tokyo 162-8601 Located three minutes’walk from Iidabashi Station,accessible via the JR Sobu Line,the Tokyo Metro Yurakuchom,Tozai,and Namboku Lines, and the Toei Oedo Line. ACCESS MAP Nagareyama Unga Ootakanomori Omiya Kasukabe Noda Campus 2641 Yamazaki, Noda-shi, Chiba Prefecture 278-8510 Kanamachi Kitasenju Akabane Tabata Keisei-Kanamachi Ikebukuro Nishi- Keisei-Takasago Nippori Katsushika Campus 6-3-1 Niijuku, Katsushika-ku, Nippori Oshiage Tokyo 125-8585 Asakusa Ueno Iidabashi Ochanomizu Shinjuku Kinshicho Akihabara Asakusabashi Kagurazaka Campus Kanda 1-3 Kagurazaka, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 162-8601 Tokyo ■ From Narita Airport Take the JR Narita Express train to Tokyo Station. Transfer to the JR Chuo Line, and take it to Ochanomizu Station. Transfer to the JR Sobu Line and take it to Iidabashi Station. Travel time: about 1 hour 55 minutes. ■ From Haneda Airport Take the Tokyo Monorail Line to Hamamatsucho Station. Transfer to the JR Yamanote Line / Keihin-Tohoku Line and take it to Akihabara Station. Transfer to the JR Sobu Line and take it to Iidabashi Station. Travel time about 45 minutes. ■ From Tokyo Station Take the JR Chuo Line to Ochanomizu Station. Transfer to the JR Sobu Line and take it to Iidabashi Station. Travel time: about 10 minutes. ■ From Ueno Station Take the JR Yamanote Line / Keihin-Tohoku Line to Akihabara Station. Transfer to the JR Sobu Line and take it to Iidabashi Station. Travel time: about 12 minutes. 9 CAMPUS MAP 10 4 Kagurazaka Buildings 12 11 1 Building No. 1 1 2 Building No. -

Tokyo Subway Ticket

17-100 October 11, 2017 Tokyo Metro will expand the number of locations where its “Tokyo Subway Ticket” special passenger tickets for foreign visitors to Japan can be purchased! Also available for purchase at certain Tokyo Metro commuter pass sales counters starting Monday, October 16, 2017 Starting Monday, October 16, 2017, Tokyo Metro Co., Ltd. (Head Office in: Taito Ward, Tokyo; President: Akiyoshi Yamamura; “Tokyo Metro” below) will make its “Tokyo Subway Tickets,” which allow foreign visitors to Japan to take unlimited rides on all nine Tokyo Metro lines and all four Toei Subway Lines for a total of thirteen lines, available for purchase at certain Tokyo Metro commuter pass sales counters in addition to preexisting sales locations. Until now, these special passenger tickets were only available for purchase at the likes of locally-based travel agencies overseas, airports, hotels and certain traveler information centers. Based on the results of a questionnaire administered to foreign visitors to Japan in which many of them cited their desire to purchase Tokyo Subway Tickets in stations, Tokyo Metro has elected to offer the tickets for purchase at certain commuter pass sales counters Going forward, Tokyo Metro will continue endeavoring to make its railway services more convenient to use for foreign visitors to Japan. For details, please see the below. 1. Commuter Pass Sales Counters Where Tokyo Subway Tickets Are Available for Purchase (15 Locations Across 14 Stations) Ueno Station, Nihombashi Station, Ikebukuro Station, Ginza Station, Shimbashi Station, Shinjuku Station, Ebisu Station, Iidabashi Station, Takadanobaba Station, Akasaka-mitsuke Station, Meiji-jingumae Station <Harajuku>, Shin-ochanomizu Station, Otemachi Station and Tokyo Station *At Ikebukuro Station, Tokyo Subway Tickets can be purchased at the commuter pass sales corners for both the Marunouchi Line and the Yurakucho Line. -

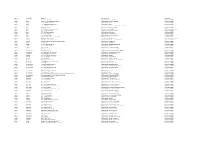

Area Locality Address Description Operator Aichi Aisai 10-1

Area Locality Address Description Operator Aichi Aisai 10-1,Kitaishikicho McDonald's Saya Ustore MobilepointBB Aichi Aisai 2283-60,Syobatachobensaiten McDonald's Syobata PIAGO MobilepointBB Aichi Ama 2-158,Nishiki,Kaniecho McDonald's Kanie MobilepointBB Aichi Ama 26-1,Nagamaki,Oharucho McDonald's Oharu MobilepointBB Aichi Anjo 1-18-2 Mikawaanjocho Tokaido Shinkansen Mikawa-Anjo Station NTT Communications Aichi Anjo 16-5 Fukamachi McDonald's FukamaPIAGO MobilepointBB Aichi Anjo 2-1-6 Mikawaanjohommachi Mikawa Anjo City Hotel NTT Communications Aichi Anjo 3-1-8 Sumiyoshicho McDonald's Anjiyoitoyokado MobilepointBB Aichi Anjo 3-5-22 Sumiyoshicho McDonald's Anjoandei MobilepointBB Aichi Anjo 36-2 Sakuraicho McDonald's Anjosakurai MobilepointBB Aichi Anjo 6-8 Hamatomicho McDonald's Anjokoronaworld MobilepointBB Aichi Anjo Yokoyamachiyohama Tekami62 McDonald's Anjo MobilepointBB Aichi Chiryu 128 Naka Nakamachi Chiryu Saintpia Hotel NTT Communications Aichi Chiryu 18-1,Nagashinochooyama McDonald's Chiryu Gyararie APITA MobilepointBB Aichi Chiryu Kamishigehara Higashi Hatsuchiyo 33-1 McDonald's 155Chiryu MobilepointBB Aichi Chita 1-1 Ichoden McDonald's Higashiura MobilepointBB Aichi Chita 1-1711 Shimizugaoka McDonald's Chitashimizugaoka MobilepointBB Aichi Chita 1-3 Aguiazaekimae McDonald's Agui MobilepointBB Aichi Chita 24-1 Tasaki McDonald's Taketoyo PIAGO MobilepointBB Aichi Chita 67?8,Ogawa,Higashiuracho McDonald's Higashiura JUSCO MobilepointBB Aichi Gamagoori 1-3,Kashimacho McDonald's Gamagoori CAINZ HOME MobilepointBB Aichi Gamagori 1-1,Yuihama,Takenoyacho -

HOSEI Global MBA Program Application Guidelines

2018 HOSEI Global MBA Program Application Guidelines Business School of Innovation Management HOSEI University Graduate Schools Business School of Innovation Management Admissions Policy Multifaceted individuals and organizations with expertise in business administration and information technology are in much demand, especially those able and willing to face the demands of today’s expanding globalization and information oriented society. The Business School of Innovation Management Global MBA Program is aimed at educating actual ‘Business individuals’ capable of encouraging and cultivating innovation such as launching businesses, reforming organizations through bold thinking and action, and calculating the potential risks involved therein. We therefore seek business persons with professional experience and a passion for business innovation. Successful applicants will have demonstrated their potential for being superior business professionals in their application documents and interview sessions. Contents 1. General Information 2. Number of Students Accepted 3. Qualifications 4. Screening 5. Selection Schedule 6. Application Documents 7. Information re Application Documents 8. Application Procedure 9. Notification of First-round Selection Results 10. Notes for Second-round Selection Examination 11. Notification of Second-round Selection Results 12. Campus Location 13. Tuition and Other Fees 14. Financial Aid 15. Request of Proxy Application for ‘Certificate of Eligibility’ (if applicable) [Privacy Policy] Personal information disclosed -

Notice of Convocation of the 30Th Ordinary General Meeting of Shareholders

Shinagawa Season Terrace (Minato-ku, Tokyo) Notice of Convocation of the 30th Ordinary General Meeting of Shareholders Shareholders’ Meeting Information ■ Date and Time Table of contents Tuesday, June 23, 2015 P2 Notice of Convocation 10:00 a.m. P4 (Reference) Exercising Your Voting Rights P5 Reference Materials for the Ordinary General ■ Place Meeting of Shareholders 4-1, Shibaura 3-chome, Minato-ku, Tokyo 【Attachments to the Notice of Convocation】 Granpark Plaza Bldg. 3F Conference Room P12 Business Report P38 Consolidated Financial Statements P42 Financial Statements (Non-consolidated) NTT Urban Development Corporation P45 Auditors’ Report (Cord: 8933, First Section of TSE) (Reference) P51 【Topics】 May, 2015 To Our Shareholders Please let me take this opportunity to thank our shareholders for your continued generous support. We are pleased to announce that the 30th Ordinary General Meeting of Shareholders will be held on June 23. This notice gives an overview of our operations in the 30th fiscal year (from April 1, 2014 to March 31, 2015) and the resolutions of the general meeting of shareholders. In the real estate market, the rush to develop new Class A buildings continued, particularly in central Tokyo, and there have been changes in the market environment, including rises in building cost and increases in land and building prices particularly around the Tokyo metropolitan area. In response to these changes, in the fiscal year under review we revised our Medium-Term Vision 2018, which we announced in the fiscal year ended March 31, 2014, including our strategies in our main businesses, and are taking steps to achieve our plan. -

Educating Andrew

EDUCATING ANDREW A PROMISE FULFILLED by Virginia Lanier Biasotto © 2006 by Virginia Biasatto All rights reserved. DEDICATION In the spring of 2003, my mother and I were sitting on her porch reminiscing about Andrew. Her questions awakened memories about the past, and I retold stories about the journey to find the solution for his inability to read. In spite of some short-term memory issues, she hung onto every word. When I was finished, she said, “You must write these stories down.” I was glad that she thought them interesting, but life’s pressures didn’t allow much time for writing. However, she was not to be dissuaded. I would get phone calls saying, “I know you are busy. But you must write those stories down.” One day it came to me that I had written them down. I wrote them down as they happened. I started to dig (I was never much at throwing things away) and low and behold I discovered a large yellowed envelope with the word “ANDREW” printed on it. Inside were a hundred or more typed pages. For a Christmas gift to my mother, I retyped them on the computer and presented them to her in book form. During her final years, she read the book about once a week. Guests in her home had to read it, too. She was very persuasive! It was her encouragement that led me to submit Educating Andrew for publication, and it is to her, Alice Darby Lanier, that I dedicate it. 2 CONTENTS Andrew ........................................................................................................................................ 6 Breakthrough .............................................................................................................................. 9 Connie ........................................................................................................................................ -

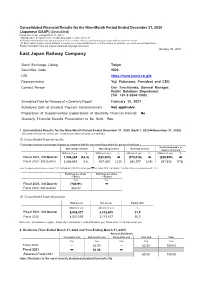

East Japan Railway Company on a Consolidated Basis, Or If the Context So Requires, on a Non-Consolidated Basis

Consolidated Financial Results for the Nine-Month Period Ended December 31, 2020 (Japanese GAAP) (Unaudited) Fiscal 2021 (Year ending March 31, 2021) “Third Quarter” means the nine months from April 1 to December 31. All financial information has been prepared in accordance with accounting principles generally accepted in Japan. “JR East” refers to East Japan Railway Company on a consolidated basis, or if the context so requires, on a non-consolidated basis. English translation from the original Japanese-language document. January 29, 2021 East Japan Railway Company Stock Exchange Listing Tokyo Securities Code 9020 URL https://www.jreast.co.jp/e Representative Yuji Fukasawa, President and CEO Contact Person Dan Tsuchizawa, General Manager, Public Relations Department (Tel. +81-3-5334-1300) Scheduled Date for Release of a Quarterly Report February 10, 2021 Scheduled Date of Dividend Payment Commencement Not applicable Preparation of Supplementary Explanations of Quarterly Financial Results: No Quarterly Financial Results Presentation to Be Held: Yes 1. Consolidated Results for the Nine-Month Period Ended December 31, 2020 (April 1, 2020-December 31, 2020) (Amounts less than one million yen, except for per share amounts, are omitted.) (1) Consolidated financial results (Percentages represent percentage changes as compared with the corresponding period in the previous fiscal year.) Profit attributable to Operating revenues Operating income Ordinary income owners of parent Millions of yen % Millions of yen % Millions of yen % Millions of