What Does a Marginalized Community Say About Its Experiences in a Two-Year, Service- Learning Project? Shanequa Smith [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Toolkit for Working with the Media

Utilizing the Media to Facilitate Social Change A Toolkit for Working with the Media WEST VIRGINIA FOUNDATION for RAPE INFORMATION and SERVICES www.fris.org 2011 Media Toolkit | 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Media Advocacy……………………………….. ……….. 3 Building a Relationship with the Media……... ……….. 3 West Virginia Media…………………………………….. 4 Tips for Working with the Media……………... ……….. 10 Letter to the Editor…………………………….. ……….. 13 Opinion Editorial (Op-Ed)…………………….. ……….. 15 Media Advisory………………………………… ……….. 17 Press/News Release………………………….. ……….. 19 Public Service Announcements……………………….. 21 Media Interviews………………………………. ……….. 22 Survivors’ Stories and the Media………………………. 23 Media Packets…………………………………. ……….. 25 Media Toolkit | 3 Media Advocacy Media advocacy can promote social change by influencing decision-makers and swaying public opinion. Organizations can use mass media outlets to change social conditions and encourage political and social intervention. When working with the media, advocates should ‘shape’ their story to incorporate social themes rather than solely focusing on individual accountability. “Develop a story that personalizes the injustice and then provide a clear picture of who is benefiting from the condition.” (Wallack et al., 1999) Merely stating that there is a problem provides no ‘call to action’ for the public. Therefore, advocates should identify a specific solution that would allow communities to take control of the issue. Sexual violence is a public health concern of social injustices. Effective Media Campaigns Local, regional or statewide campaigns can provide a forum for prevention, outreach and raising awareness to create social change. This toolkit will enhance advocates’ abilities to utilize the media for campaigns and other events. Campaigns can include: public service announcements (PSAs), awareness events (Take Back the Night; The Clothesline Project), media interviews, coordinated events at area schools or college campuses, position papers, etc. -

2020 MLB Ump Media Guide

the 2020 Umpire media gUide Major League Baseball and its 30 Clubs remember longtime umpires Chuck Meriwether (left) and Eric Cooper (right), who both passed away last October. During his 23-year career, Meriwether umpired over 2,500 regular season games in addition to 49 Postseason games, including eight World Series contests, and two All-Star Games. Cooper worked over 2,800 regular season games during his 24-year career and was on the feld for 70 Postseason games, including seven Fall Classic games, and one Midsummer Classic. The 2020 Major League Baseball Umpire Guide was published by the MLB Communications Department. EditEd by: Michael Teevan and Donald Muller, MLB Communications. Editorial assistance provided by: Paul Koehler. Special thanks to the MLB Umpiring Department; the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum; and the late David Vincent of Retrosheet.org. Photo Credits: Getty Images Sport, MLB Photos via Getty Images Sport, and the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Copyright © 2020, the offiCe of the Commissioner of BaseBall 1 taBle of Contents MLB Executive Biographies ...................................................................................................... 3 Pronunciation Guide for Major League Umpires .................................................................. 8 MLB Umpire Observers ..........................................................................................................12 Umps Care Charities .................................................................................................................14 -

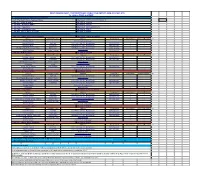

Morgantown 2015 EEO Public File Report

WEST VIRGINIA RADIO CORPORATION EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT JUNE 2014- MAY 2015 for stations WVAQ and WAJR A. Full-Time Vacancies Filled During Past Year 1. Job Title: Digital Sales Representatives Date Filled: 7/28/14 and 8/4/14 (Hired 2) 2. Job Title: News Reporter Date Filled: 10/29/14 3. Job Title: Air Talent, WVAQ Date Filled: 2/23/15 4. Job Title: Copy Witer Date Filled: 3/2/15 and 3/16/15 5. Job Title: Account Executive Date Filled: 3/30/15 6. Job Title: Sports Video Journalist Date Filled: 4/10/15 B. Recruitment/Referral Sources Used to Seek Candidates for Each Vacancy 1. Job Title: Digital Sales Representatives Date Filled: 7/28/14 and 8/4/14 Source Contact Person Address Telephone # Interviewed Referred Person Hired Word of Mouth from current employees Internal Posting Jodi Hart 1251 Earl Core Rd., Morgantown 304-296-0029 1 1 Dominion Post Classifieds 1251 Earl Core Rd., Morgantown 304-292-6301 1 1 WVAQ & WAJR Facebook Pages Bill Vernon 1251 Earl Core Rd., Morgantown online posting 1 WAJR Website Patrick Rinehart www.wajr.com 304-296-0029 2. Job Title: News Reporter Date Filled: 10/29/14 Source Contact Person Address Telephone # Interviewed Referred Person Hired Internal Posting Jodi Hart 1251 Earl Core Rd., Morgantown 304-296-0029 Dominion Post Classifieds 1251 Earl Core Rd., Morgantown 304-292-6301 WV Broadcasters Assoc Michele Crist www.wvba.com All Access online www.allaccess.com On-air ads on WAJR Gary Mertins 1251 Earl Core Rd., Morgantown 304-296-0029 Word of Mouth from current employees 1 1 3. -

Current Office Holders

Federal Name Party Office Term Next Election Joe Biden Democrat U.S President 4 Years 2024 Kamala Harris Democrat U.S. Vice President 4 Years 2024 Joe Manchin Democratic U.S. Senate 6 Years 2024 Shelley Moore Capito Republican U.S. Senate 6 Years 2026 David McKinley Republican U.S House, District 1 2 Years 2022 Alexander Mooney Republican U.S. House, District 2 2 Years 2022 Carol Miller Republican U.S. House, District 3 2 Years 2022 State Name Party Office Term Next Election Jim Justice Republican Governor 4 Years 2024 Mac Warner Republican West Virginia Secretary of State 4 Years 2024 John "JB" McCuskey Republican West Virginia State Auditor 4 Years 2024 Riley Moore Republican West Virginia State Treasurer 4 Years 2024 Patrick Morrisey Republican Attorney General of West Virginia 4 Years 2024 Kent Leonhardt Republican West Virginia Commissioner of Agriculture 4 Years 2024 West Virginia State Senate Name Party District Next election Ryan W. Weld Republican 1 2024 William Ihlenfeld Democrat 1 2022 Mike Maroney Republican 2 2024 Charles Clements Republican 2 2022 Donna J. Boley Republican 3 2024 Mike Azinger Republican 3 2022 Amy Grady Republican 4 2024 Eric J. Tarr Republican 4 2022 Robert H. Plymale Democrat 5 2024 Mike Woelfel Democrat 5 2022 Chandler Swope Republican 6 2024 Mark R Maynard Republican 6 2022 Rupie Phillips Republican 7 2024 Ron Stollings Democrat 7 2022 Glenn Jeffries Democrat 8 2024 Richard Lindsay Democrat 8 2022 David Stover Republican 9 2024 Rollan A. Roberts Republican 9 2022 Jack Woodrum Republican 10 2024 Stephen Baldwin Democrat 10 2022 Robert Karnes Republican 11 2024 Bill Hamilton Republican 11 2022 Patrick Martin Republican 12 2024 Mike Romano Democrat 12 2022 Mike Caputo Democrat 13 2024 Robert D. -

Inclement Weather Policy

Inclement Weather Policy College policy is to maintain normal operations in adverse weather conditions. However, if conditions warrant, one of three levels of closure may be implemented. The examples below are an attempt to define increasing levels of urgency. In the end, the nature of the emergency will determine what services should continue and who is then essential to the continued operation of the campus. The distinction between the levels described below is blurred by the specifics of the circumstance at hand. The following is offered as a general guideline. All members of the campus community are valued and urged to use good judgment in deciding if they can safely travel to and from campus in adverse weather conditions. Faculty are urged to make attendance policy considerations for the difficulties that some commuter students may encounter due to adverse weather conditions. These students should be provided the opportunities to make up missed assignments. I. Levels of closure Level I. Class Delay or Early Dismissal: Two hour delay, or early cancellation of classes Examples: ice or snow on roads that can be cleared within two hours of when classes normally begin (8:00 a.m.) or flash flood that will cause dangerous road conditions before the normal close of classes (4:00 p.m.). On duty: all staff and administrators Release: students and faculty Level II. Classes Dismissed: Non-instructional day, campus services open Examples: snow day, recognition of a local or national incident. On duty: all staff and administrators Release: students and faculty Level III. Campus Closure: Inability to conduct business Examples: complete loss of power; response to a local or national incident; President issues a directive to release non-essential personnel; or Governor issues a state of emergency. -

FLOOD V. KUHN Supreme Court of the United States 407 U.S

FLOOD v. KUHN Supreme Court of the United States 407 U.S. 258, 92 S. Ct. 2099 (1972) Mr. Justice BLACKMUN delivered the opinion of the Court. For the third time in 50 years the Court is asked specifically to rule that professional baseball's reserve system is within the reach of the federal antitrust laws.1 . 1 The reserve system, publicly introduced into baseball contracts in 1887, see Metropolitan Exhibition Co. v. Ewing, 42 F. 198, 202--204 (C.C.SDNY 1890), centers in the uniformity of player contracts; the confinement of the player to the club that has him under the contract; the assignability of the player's contract; and the ability of the club annually to renew the contract unilaterally, subject to a stated salary minimum. Thus A. Rule 3 of the Major League Rules provides in part: '(a) UNIFORM CONTRACT. To preserve morale and to produce the similarity of conditions necessary to keen competition, the contracts between all clubs and their players in the Major Leagues shall be in a single form which shall be prescribed by the Major League Executive Council. No club shall make a contract different from the uniform contract or a contract containing a non-reserve clause, except with the written approval of the Commissioner. '(g) TAMPERING. To preserve discipline and competition, and to prevent the enticement of players, coaches, managers and umpires, there shall be no negotiations or dealings respecting employment, either present or prospective, between any player, coach or manager and any club other than the club with which he is under contract or acceptance of terms, or by which he is reserved, or which has the player on its Negotiation List, or between any umpire and any league other than the league with which he is under contract or acceptance of terms, unless the club or league with which he is connected shall have, in writing, expressly authorized such negotiations or dealings prior to their commencement.' B. -

America Celebrates National Catfish Month! by Jeremy Robbins on Local Economy

MISSISSIPPI DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE & COMMERCE • ANDY GIPSON, COMMISSIONER VOLUME 90 NUMBER 16 AUGUST 15, 2018 JACKSON, MS America Celebrates National Catfish Month! By Jeremy Robbins on local economy. is difficult to select just one farmer Barlow. and radio ads; special features dur- The Catfish Institute “The catfish industry is fairly from each of these states, those These Farmers of the Year are ing National Catfish Month; and in unique among agriculture indus- who are selected embody the spirit used by TCI in various advertising their very own brochure to highlight Each August since 1984, when tries with respect to its economic of the American Farmer. All of the campaigns throughout the year, in- each farmer’s favorite catfish recipe. President Ronald Reagan declared impact,” says Roger Barlow, TCI Farmers of the Year have made sig- cluding print advertisements, events For more information about U.S. it as such, the nation rolls up its president and executive director of nificant contributions to the U.S. such as Boston’s Seafood Expo Farm-Raised Catfish or The Catfish sleeves to celebrate National Catfish Catfish Farmers of America. “Ev- Farm-Raised Catfish Industry, stated North America; billboard, television Institute, please visit UScatfish.com. Month. And there is plenty of rea- ery element of our industry has an son to celebrate, particularly here economic return that benefits the in Mississippi, where, along with areas where the fish are grown, as Alabama and Arkansas, the major- well as the entire region. The fin- ity of the nation’s catfish farms are gerlings are hatched locally; the feed located. -

Attachment a DA 19-526 Renewal of License Applications Accepted for Filing

Attachment A DA 19-526 Renewal of License Applications Accepted for Filing File Number Service Callsign Facility ID Frequency City State Licensee 0000072254 FL WMVK-LP 124828 107.3 MHz PERRYVILLE MD STATE OF MARYLAND, MDOT, MARYLAND TRANSIT ADMN. 0000072255 FL WTTZ-LP 193908 93.5 MHz BALTIMORE MD STATE OF MARYLAND, MDOT, MARYLAND TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION 0000072258 FX W253BH 53096 98.5 MHz BLACKSBURG VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072259 FX W247CQ 79178 97.3 MHz LYNCHBURG VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072260 FX W264CM 93126 100.7 MHz MARTINSVILLE VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072261 FX W279AC 70360 103.7 MHz ROANOKE VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072262 FX W243BT 86730 96.5 MHz WAYNESBORO VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072263 FX W241AL 142568 96.1 MHz MARION VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072265 FM WVRW 170948 107.7 MHz GLENVILLE WV DELLA JANE WOOFTER 0000072267 AM WESR 18385 1330 kHz ONLEY-ONANCOCK VA EASTERN SHORE RADIO, INC. 0000072268 FM WESR-FM 18386 103.3 MHz ONLEY-ONANCOCK VA EASTERN SHORE RADIO, INC. 0000072270 FX W289CE 157774 105.7 MHz ONLEY-ONANCOCK VA EASTERN SHORE RADIO, INC. 0000072271 FM WOTR 1103 96.3 MHz WESTON WV DELLA JANE WOOFTER 0000072274 AM WHAW 63489 980 kHz LOST CREEK WV DELLA JANE WOOFTER 0000072285 FX W206AY 91849 89.1 MHz FRUITLAND MD CALVARY CHAPEL OF TWIN FALLS, INC. 0000072287 FX W284BB 141155 104.7 MHz WISE VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072288 FX W295AI 142575 106.9 MHz MARION VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072293 FM WXAF 39869 90.9 MHz CHARLESTON WV SHOFAR BROADCASTING CORPORATION 0000072294 FX W204BH 92374 88.7 MHz BOONES MILL VA CALVARY CHAPEL OF TWIN FALLS, INC. -

Citizen Initiatives Teacher Training Gas Taxes

DEFENDING AGAINST SECURITY BREACHES PAGE 5 March 2015 Citizen Initiatives Teacher Training Gas Taxes AmericA’s innovAtors believe in nuclear energy’s future. DR. LESLIE DEWAN technology innovAtor Forbes 30 under 30 I’m developing innovative technology that takes used nuclear fuel and generates electricity to power our future and protect the environment. America’s innovators are discovering advanced nuclear energy supplies nearly one-fifth nuclear energy technologies to smartly and of our electricity. in a recent poll, 85% of safely meet our growing electricity needs Americans believe nuclear energy should play while preventing greenhouse gases. the same or greater future role. bill gates and Jose reyes are also advancing nuclear energy options that are scalable and incorporate new safety approaches. these designs will power future generations and solve global challenges, such as water desalination. Get the facts at nei.org/future #futureofenergy CLIENT: NEI (Nuclear Energy Institute) PUB: State Legislatures Magazine RUN DATE: February SIZE: 7.5” x 9.875” Full Page VER.: Future/Leslie - Full Page Ad 4CP: Executive Director MARCH 2015 VOL. 41 NO. 3 | CONTENTS William T. Pound Director of Communications Karen Hansen Editor Julie Lays STATE LEGISLATURES Contributing Editors Jane Carroll Andrade Mary Winter NCSL’s national magazine of policy and politics Web Editors Edward P. Smith Mark Wolf Copy Editor Leann Stelzer Advertising Sales FEATURES DEPARTMENTS Manager LeAnn Hoff (303) 364-7700 Contributors 14 A LACK OF INITIATIVE 4 SHORT TAKES ON -

Official Game Information

Official Game Information Yankee Stadium • One East 161st Street • Bronx, NY 10451 Phone: (718) 579-4460 • E-mail: [email protected] • Twitter: @yankeespr & @losyankeespr World Series Champions: 1923, ’27-28, ’32, ’36-39, ’41, ’43, ’47, ’49-53, ’56, ’58, ’61-62, ’77-78, ’96, ’98-2000, ’09 YANKEES BY THE NUMBERS NOTE 2014 (2013) New York Yankees (70-66) vs. BOSTON RED SOX (61-77) Standing in AL East: .............2nd, -9.5 RHP Hiroki Kuroda (9-8, 3.88) vs. RHP Anthony Ranaudo (3-0, 4.50) Games Behind for Second WC ....... -5.0 Current Streak: .....................Lost 3 Wednesday, September 3, 2014 • Yankee Stadium • 7:05 P.M. ET Home Record: .............33-32 (46-35) Road Record:. 37-34 (44-37) Game #137 • Home Game #66 • TV: YES/ESPN • Radio: WFAN 660AM/101.9FM Day Record: ................28-19 (32-24) Night Record: ..............42-47 (53-53) AT A GLANCE: Tonight the Yankees play the second game of O CAPTAIN, MY CAPTAIN: The Yankees will hold a special pregame Pre-All-Star .................47-47 (51-44) a three-game series vs. Boston…is also the second game of a Post-All-Star ................23-19 (34-33) ceremony for Derek Jeter on Sunday…all fans are encouraged vs. AL East: ................. 24-29 (37-39) nine-game homestand, which also features games vs. Kansas to be in their seats by noon… those in attendance will receive a vs. AL Central: .............. 18-14 (22-11) City (9/5-7) and Tampa Bay (9/9-11)… went 3-4 on their last limited-edition commemorative coin recognizing the occasion. -

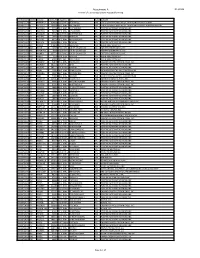

List of Radio Stations in West Virginia

Not logged in Talk Contributions Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Search Wikipedia List of radio stations in West Virginia From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Main page The following is a list of FCC-licensed radio stations in the U.S. state of West Virginia, which can Contents be sorted by their call signs, frequencies, cities of license, licensees, and programming formats. Featured content Current events Contents [hide] Random article 1 List of radio stations Donate to Wikipedia 2 Defunct Wikipedia store 3 See also 4 References Interaction 5 Bibliography Help 6 External links About Wikipedia 7 Images Community portal Recent changes Contact page List of radio stations [edit] Tools This list is complete and up to date as of December 17, 2018. What links here Related changes Call City of [2][3] [4] Upload file Frequency Licensee Format sign License [1][2] Special pages open in browser PRO version Are you a developer? Try out the HTML to PDF API pdfcrowd.com Permanent link Princeton Broadcasting, WAEY 1490 AM Princeton Southern gospel Page information Inc. Wikidata item Webster Cite this page WAFD 100.3 FM Summit Media, Inc. Hot adult contemporary Springs Print/export WAGE- Southern Appalachian 106.5 FM Oak Hill Variety Create a book LP Labor School Download as PDF West Virginia Radio Printable version WAJR 1440 AM Morgantown News/Talk/Sports Corporation In other projects WAJR- West Virginia Radio 103.3 FM Salem News/Talk/Sports Wikimedia Commons FM Corporation of Salem Languages West Virginia – Virginia WAMN 1050 AM Green Valley Classic country Add links Media, LLC WAMX 106.3 FM Milton Capstar TX LLC Classic rock WASP- Spring Valley High 104.5 FM Huntington Variety LP School (Students) WAXE- Coal Mountain 106.9 FM St. -

NEW YORK YANKEES (33-23) Vs. BOSTON RED SOX (32-26) Standing in AL East

OFFICIAL GAME INFORMATION YANKEE STADIUM • ONE EAST 161ST STREET • BRONX, NY 10451 PHONE: (718) 579-4460 • E-MAIL: [email protected] • SOCIAL MEDIA: @YankeesPR & @LosYankeesPR WORLD SERIES CHAMPIONS: 1923, ’27-28, ’32, ’36-39, ’41, ’43, ’47, ’49-53, ’56, ’58, ’61-62, ’77-78, ’96, ’98-2000, ’09 YANKEES BY THE NUMBERS NOTE 2017 (2016) NEW YORK YANKEES (33-23) vs. BOSTON RED SOX (32-26) Standing in AL East: ...........1st, +2.0G RHP Michael Pineda (6-3, 3.76) vs. LHP David Price (1-0, 3.00) Current Streak: ....................Won 1 Current Homestand: .................1-1 Recent Road Trip .....................3-4 Thursday, June 8, 2017 • Yankee Stadium • 7:05 p.m. ET Home Record: ...............18-9 (48-33) Game #57 Home Game #28 TV: YES/ESPN Radio: WFAN 660AM/101.9FM (English), WADO 1280AM (Spanish) Road Record: .............. 15-14 (36-45) • • • Day Record: .................12-8 (26-27) Night Record: ............. 21-15 (58-51) AT A GLANCE: Tonight the Yankees play the rubber game ALL RISE: RF Aaron Judge had his career-high 9G hitting Pre-All-Star ................ 33-23 (44-44) Post-All-Star ..................0-0 (40-34) of their 3G series vs. Boston… square off with Baltimore for streak snapped in Wednesday's win vs. Boston… over his last vs. AL East: ................ 16-13 (35-41) 3G this weekend… completed their recent road trip with a 10G, is hitting .342/.457/.684 (13-for-38) with 8R, 4 doubles, vs. AL Central: ................6-3 (21-12) 3-4 mark, going 1-2 at Baltimore, then 2-2 at Toronto.