Phoenix (Mythology)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visiting the Pyramids with Bennu

EDITORIAL WEEBLE Visiting the Pyramids with Bennu SUSO MONFORTE ILLUSTRATIONS VICO CÓCERES http://editorialweeble.com Visiting the pyramids with Bennu 2015 Editorial Weeble Author: Suso Monforte Illustrations: Vico Cóceres Translation: Irene Guzmán Licence: Creative Commons Attribution- http://editorialweeble.com NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ Madrid, Spain, March 2015 the author suso monforte Suso Monforte is the father of two children aged 6 and 10 years old. He is a member of the Parents’ Association at Herrero Infant and Primary School, a state school in Castellón de la Plana. Suso is an advocate of free, high-quality, state education, where parents can voice their opinions, make decisions and collaborate. Suso actively participates in order to achieve an education where the knowledge acquired goes beyond that received in the classroom. The street, museums, markets and nature are also educational spaces. This is the first book he has written for our publishing house. It brings together the history of Ancient Egypt and the country’s modern day situation, all in the company of two children, Miguel and Bennu. Email: [email protected] the illustrator vico cóceres Vico Cóceres is a young Argentinian illustrator, aged 24, who has a well-defined, carefree style which suits that of our project perfectly. Her work has been published in several newspapers and magazines in Latin America. This is the first book that Vico has illustrated for our publishing house. She has produced illustrations which are full of life, very modern and refreshing. We are sure that we will continue to collaborate with her in the future. -

Ancient Greece. ¡ the Basilisc Was an Extremely Deadly Serpent, Whose Touch Alone Could Wither Plants and Kill a Man

Ancient Greece. ¡ The Basilisc was an extremely deadly serpent, whose touch alone could wither plants and kill a man. ¡ The creature is later shown in the form of a serpent- tailed bird. ¡ Cerberus was the gigantic hound which guarded the gates of Haides. ¡ He was posted to prevent ghosts of the dead from leaving the underworld. ¡ Cerberus was described as a three- headed dog with a serpent's tail, a mane of snakes, and a lion's claws. The Chimera The Chimera was a monstrous beast with the body and maned head of a lion, a goat's head rising from its back, a set of goat-udders, and a serpents tail. It could also breath fire. The hero Bellerophon rode into battle to kill it on the back of the winged horse Pegasus. ¡ The Gryphon or Griffin was a beast with the head and wings of an eagle and the body of a lion. ¡ A tribe of the beasts guarded rich gold deposits in certain mountains. HYDRA was a gigantic, nine-headed water-serpent. Hercules was sent to destroy her as one of his twelve labours, but for each of her heads that he decapitated, two more sprang forth. So he used burning brands to stop the heads regenerating. The Gorgons The Gorgons were three powerful, winged daemons named Medusa, Sthenno and Euryale. Of the three sisters only Medousa was mortal, and so it was her head which the King commanded the young hero Perseus to fetch. He accomplished this with the help of the gods who equipped him with a reflective shield, curved sword, winged boots and helm of invisibility. -

Bl12-2Pgs.Pdf

Volume 12, Number 2 $8.50 ARTISTS’ BOOKSbBOOKBINDINGbPAPERCRAFTbCALLIGRAPHY Volume 12, Number 2, February 2015. 3 Creating Double-Stroke Letterforms by Martin Jackson 8 Dancing Letters Scholarship Fund 12 Creating a Scroll-Tip Pilot Parallel Pen by Carol DuBosch 14 Between Verse and Vision by Risa Gettler 22 Heraldry for Calligraphy by Helen Scholes 28 Spinning Letters by Judy Black, Susan Gunter, and Marilyn Rice 30 A Passionate Gallery 37 New Tools & Materials 38 Passionate Pen Envelopes 40 Leporello Accordion Book by Carol DuBosch 42 Contributors / credits 47 Subscription information A Few Excerpts from the Now Intergalactic Song Fest and Cosmic Miscelany. 2014. Risa Gettler. Hand- lettered and illustrated manuscript book of nineteen poems by John S. Tumlin. 40 pages, images and text on recto pages only. Leather binding is by Edna Wright. Each page is held in an open-front sleeve that is sewn into the binding. The front of the sleeve serves as a frame for its book page (which can be removed). 22" x 13" x 4". Photo by Risa Gettler. “Between Verse and Vision,” page 14. Bound & Lettered b Spring 2015 1 All calligraphy shown in this article is by the author. CREATING DOUBLE-STROKE LETTERFORMS BY MARTIN JACKSON There are two methods to create double-stroke letterforms. One is to use a scroll (or split) nib or pen. These are made to automatically produce double strokes – the pen/nib does it for you. A variety of writing instruments offer scroll versions: Mitchell makes six differ- ent scroll dip pen nibs, Manuscript offers two different scroll nibs (Scroll 4 and Scroll 6) for some of its fountain pens, and four of the Automatic pens have split nibs (numbers 7, 8, 9, and 10). -

(101955) Bennu from OSIRIS-Rex Imaging and Thermal Analysis

ARTICLES https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-019-0731-1 Properties of rubble-pile asteroid (101955) Bennu from OSIRIS-REx imaging and thermal analysis D. N. DellaGiustina 1,26*, J. P. Emery 2,26*, D. R. Golish1, B. Rozitis3, C. A. Bennett1, K. N. Burke 1, R.-L. Ballouz 1, K. J. Becker 1, P. R. Christensen4, C. Y. Drouet d’Aubigny1, V. E. Hamilton 5, D. C. Reuter6, B. Rizk 1, A. A. Simon6, E. Asphaug1, J. L. Bandfield 7, O. S. Barnouin 8, M. A. Barucci 9, E. B. Bierhaus10, R. P. Binzel11, W. F. Bottke5, N. E. Bowles12, H. Campins13, B. C. Clark7, B. E. Clark14, H. C. Connolly Jr. 15, M. G. Daly 16, J. de Leon 17, M. Delbo’18, J. D. P. Deshapriya9, C. M. Elder19, S. Fornasier9, C. W. Hergenrother1, E. S. Howell1, E. R. Jawin20, H. H. Kaplan5, T. R. Kareta 1, L. Le Corre 21, J.-Y. Li21, J. Licandro17, L. F. Lim6, P. Michel 18, J. Molaro21, M. C. Nolan 1, M. Pajola 22, M. Popescu 17, J. L. Rizos Garcia 17, A. Ryan18, S. R. Schwartz 1, N. Shultz1, M. A. Siegler21, P. H. Smith1, E. Tatsumi23, C. A. Thomas24, K. J. Walsh 5, C. W. V. Wolner1, X.-D. Zou21, D. S. Lauretta 1 and The OSIRIS-REx Team25 Establishing the abundance and physical properties of regolith and boulders on asteroids is crucial for understanding the for- mation and degradation mechanisms at work on their surfaces. Using images and thermal data from NASA’s Origins, Spectral Interpretation, Resource Identification, and Security-Regolith Explorer (OSIRIS-REx) spacecraft, we show that asteroid (101955) Bennu’s surface is globally rough, dense with boulders, and low in albedo. -

Theosophical Symbology Some Hints Towards Interpretation of the Symbolism of the Seal of the Society

Theosophical Siftings Theosophical Symbology Vol 3, No 4 Theosophical Symbology Some Hints Towards Interpretation of the Symbolism of the Seal of the Society by G.R.S. Mead, F.T.S. Reprinted from “Theosophical Siftings” Volume 3 The Theosophical Publishing Society, England "A combination and a form, indeed, Where every god did seem to set his seal, To give the world assurance of a MAN." As the question is often asked, What is the meaning of the Seal of the Society, it may not be unprofitable to attempt a rough outline of some of the infinite interpretations that can be discovered therein. When, however, we consider that the whole of our philosophical literature is but a small contribution to the unriddling of this collective enigma of the sphinx of all sciences, religions and philosophies, it will be seen that no more than the barest outlines can be sketched in a short paper. In the first place, we are told that to every symbol, glyph and emblem there are seven keys, or rather, that the key may be turned seven times, corresponding to all the septenaries in nature and in man. We might even suppose, by using the law of analogy, that each of the seven keys might be turned seven times. So that if we were to suggest that these keys may be named the physiological, astronomical, cosmic, psychic, intellectual and spiritual, of which divine interpretation is the master-key, we should still be on our guard lest we may have confounded some of the turnings with the keys themselves. -

The Wild Boar from San Rossore

209.qxp 01-12-2009 12:04 Side 55 UDSTILLINGSHISTORIER OG UDSTILLINGSETIK ● NORDISK MUSEOLOGI 2009 ● 2, S. 55-79 Speaking to the Eye: The wild boar from San Rossore LIV EMMA THORSEN* Abstract: The article discusses a taxidermy work of a wild boar fighting two dogs. The tableau was made in 1824 by the Italian scientist Paolo Savi, director of the Natural History Museum in Pisa from 1823-1840. The point of departure is the sense of awe this brilliantly produced tableau evokes in the spectator. If an object could talk, what does the wild boar communicate? Stuffed animals are objects that operate in natural history exhibitions as well in several other contexts. They resist a standard classification, belonging to neither nature nor culture. The wild boar in question illustrates this ambiguity. To decode the tale of the boar, it is establis- hed as a centre in a network that connects Savi’s scientific and personal knowled- ge, the wild boar as a noble trophy, the development of the wild boar hunt in Tus- cany, perceptions of the boar and the connection between science and art. Key words: Natural history museum, taxidermy, wild boar, wild boar hunt, the wild boar in art, ornithology, natural history in Tuscany, Museo di Storia Naturale e del Territorio, Paolo Savi. In 1821, a giant male wild boar was killed at There is a complex history to this wild boar. San Rossore, the hunting property of the We have to understand the important role this Grand Duke of Toscana. It was killed during a species played in Italian and European hun- hunt arranged in honour of prominent guests ting tradition, the link between natural histo- of Ferdinand III. -

Serpent Symbols and Salvation in the Ancient Near East and the Book of Mormon

Journal of Book of Mormon Studies Volume 10 Number 2 Article 8 7-31-2001 Serpent Symbols and Salvation in the Ancient Near East and the Book of Mormon Andrew C. Skinner Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Skinner, Andrew C. (2001) "Serpent Symbols and Salvation in the Ancient Near East and the Book of Mormon," Journal of Book of Mormon Studies: Vol. 10 : No. 2 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms/vol10/iss2/8 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Book of Mormon Studies by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title Serpent Symbols and Salvation in the Ancient Near East and the Book of Mormon Author(s) Andrew C. Skinner Reference Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 10/2 (2001): 42–55, 70–71. ISSN 1065-9366 (print), 2168-3158 (online) Abstract The serpent is often used to represent one of two things: Christ or Satan. This article synthesizes evi- dence from Egypt, Mesopotamia, Phoenicia, Greece, and Jerusalem to explain the reason for this duality. Many scholars suggest that the symbol of the serpent was used anciently to represent Jesus Christ but that Satan distorted the symbol, thereby creating this para- dox. The dual nature of the serpent is incorporated into the Old Testament, the New Testament, and the Book of Mormon. erpent ymbols & SSalvation in the ancient near east and the book of mormon andrew c. -

Dragon and the Phoenix Teacher's Notes.Indd

Usborne English The Dragon and the Phoenix • Teacher’s notes Author: traditi onal, retold by Lesley Sims Reader level: Elementary Word count: 235 Lexile level: 350L Text type: Folk tale from China About the story A dragon and a phoenix live on opposite sides of a magic river. One day they meet on an island and discover a shiny pebble. The dragon washes it and the phoenix polishes it unti l it becomes a pearl. Its brilliant light att racts the att enti on of the Queen of Heaven, and that night she sends a guard to steal it while the dragon and phoenix are sleeping. The next morning, the dragon and phoenix search everywhere and eventually see their pearl shining in the sky. They fl y up to retrieve it, but the pearl falls down and becomes a lake on the ground below. The dragon and the phoenix lie down beside the lake, and are sti ll there today in the guise of Dragon Mountain and Phoenix Mountain. The story is based on The Bright Pearl, a Chinese folk tale. Chinese dragons are typically depicted without wings (although they are able to fl y), and are associated with water and wisdom. Chinese phoenixes are immortal, and do not need to die and then be reborn. They are associated with loyalty and honesty. The dragon and phoenix are oft en linked to the male yin and female yang qualiti es, and in the past, a Chinese emperor’s robes would typically be embroidered with dragons and an empress’s with phoenixes. -

Benjamin Franklin (10 Vols., New York, 1905- 7), 5:167

The American Aesthetic of Franklin's Visual Creations ENJAMIN FRANKLIN'S VISUAL CREATIONS—his cartoons, designs for flags and paper money, emblems and devices— Breveal an underlying American aesthetic, i.e., an egalitarian and nationalistic impulse. Although these implications may be dis- cerned in a number of his visual creations, I will restrict this essay to four: first, the cartoon of Hercules and the Wagoneer that appeared in Franklin's pamphlet Plain Truth in 1747; second, the flags of the Associator companies of December 1747; third, the cut-snake cartoon of May 1754; and fourth, his designs for the first United States Continental currency in 1775 and 1776. These four devices or groups of devices afford a reasonable basis for generalizations concerning Franklin's visual creations. And since the conclusions shed light upon Franklin's notorious comments comparing the eagle as the emblem of the United States to the turkey ("a much more respectable bird and withal a true original Native of America"),1 I will discuss that opinion in an appendix. My premise (which will only be partially proven during the fol- lowing discussion) is that Franklin was an extraordinarily knowl- edgeable student of visual symbols, devices, and heraldry. Almost all eighteenth-century British and American printers used ornaments and illustrations. Many printers, including Franklin, made their own woodcuts and carefully designed the visual appearance of their broad- sides, newspapers, pamphlets, and books. Franklin's uses of the visual arts are distinguished from those of other colonial printers by his artistic creativity and by his interest in and scholarly knowledge of the general subject. -

Curiosity Killed the Bird: Arbitrary Hunting of Harpy Eagles Harpia

Cotinga30-080617:Cotinga 6/17/2008 8:11 AM Page 12 Cotinga 30 Curiosity killed the bird: arbitrary hunting of Harpy Eagles Harpia harpyja on an agricultural frontier in southern Brazilian Amazonia Cristiano Trapé Trinca, Stephen F. Ferrari and Alexander C. Lees Received 11 December 2006; final revision accepted 4 October 2007 Cotinga 30 (2008): 12–15 Durante pesquisas ecológicas na fronteira agrícola do norte do Mato Grosso, foram registrados vários casos de abate de harpias Harpia harpyja por caçadores locais, motivados por simples curiosidade ou sua intolerância ao suposto perigo para suas criações domésticas. A caça arbitrária de harpias não parece ser muito freqüente, mas pode ter um impacto relativamente grande sobre as populações locais, considerando sua baixa densidade, e também para o ecossistema, por causa do papel ecológico da espécie, como um predador de topo. Entre as possíveis estratégias mitigadoras, sugere-se utilizar a harpia como espécie bandeira para o desenvolvimento de programas de conservação na região. With adult female body weights of up to 10 kg, The study was conducted in the municipalities Harpy Eagles Harpia harpyja (Fig. 1) are the New of Alta Floresta (09º53’S 56º28’W) and Nova World’s largest raptors, and occur in tropical forests Bandeirantes (09º11’S 61º57’W), in northern Mato from Middle America to northern Argentina4,14,17,22. Grosso, Brazil. Both are typical Amazonian They are relatively sensitive to anthropogenic frontier towns, characterised by immigration from disturbance and are among the first species to southern and eastern Brazil, and ongoing disappear from areas colonised by humans. fragmentation of the original forest cover. -

The Mediaeval Bestiary and Its Textual Tradition

THE MEDIAEVAL BESTIARY AND ITS TEXTUAL TRADITION Volume 1: Text Patricia Stewart A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2012 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/3628 This item is protected by original copyright The Mediaeval Bestiary and its Textual Tradition Patricia Stewart This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 17th August, 2012 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, Patricia Stewart, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 88 000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September, 2007 and as a candidate for the degree of PhD in May, 2008; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2007 and 2012. Date 17th August, 2012 signature of candidate ……… 2. Supervisor’s declaration: I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of PhD in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. Date 17th August, 2012 signature of supervisor ……… 3. Permission for electronic publication: (to be signed by both candidate and supervisor) In submitting this thesis to the University of St Andrews I understand that I am giving permission for it to be made available for use in accordance with the regulations of the University Library for the time being in force, subject to any copyright vested in the work not being affected thereby. -

California Folklore Miscellany Index

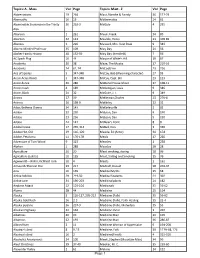

Topics: A - Mass Vol Page Topics: Mast - Z Vol Page Abbreviations 19 264 Mast, Blanche & Family 36 127-29 Abernathy 16 13 Mathematics 24 62 Abominable Snowman in the Trinity 26 262-3 Mattole 4 295 Alps Abortion 1 261 Mauk, Frank 34 89 Abortion 22 143 Mauldin, Henry 23 378-89 Abscess 1 226 Maxwell, Mrs. Vest Peak 9 343 Absent-Minded Professor 35 109 May Day 21 56 Absher Family History 38 152-59 May Day (Kentfield) 7 56 AC Spark Plug 16 44 Mayor of White's Hill 10 67 Accidents 20 38 Maze, The Mystic 17 210-16 Accidents 24 61, 74 McCool,Finn 23 256 Ace of Spades 5 347-348 McCoy, Bob (Wyoming character) 27 93 Acorn Acres Ranch 5 347-348 McCoy, Capt. Bill 23 123 Acorn dance 36 286 McDonal House Ghost 37 108-11 Acorn mush 4 189 McGettigan, Louis 9 346 Acorn, Black 24 32 McGuire, J. I. 9 349 Acorns 17 39 McKiernan,Charles 23 276-8 Actress 20 198-9 McKinley 22 32 Adair, Bethena Owens 34 143 McKinleyville 2 82 Adobe 22 230 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 23 236 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 24 147 McNear's Point 8 8 Adobe house 17 265, 314 McNeil, Dan 3 336 Adobe Hut, Old 19 116, 120 Meade, Ed (Actor) 34 154 Adobe, Petaluma 11 176-178 Meals 17 266 Adventure of Tom Wood 9 323 Measles 1 238 Afghan 1 288 Measles 20 28 Agriculture 20 20 Meat smoking, storing 28 96 Agriculture (Loleta) 10 135 Meat, Salting and Smoking 15 76 Agwiworld---WWII, Richfield Tank 38 4 Meats 1 161 Aimee McPherson Poe 29 217 Medcalf, Donald 28 203-07 Ainu 16 139 Medical Myths 15 68 Airline folklore 29 219-50 Medical Students 21 302 Airline Lore 34 190-203 Medicinal plants 24 182 Airplane