An Interview with Milton Friedman Russ Roberts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mont Pelerin Society

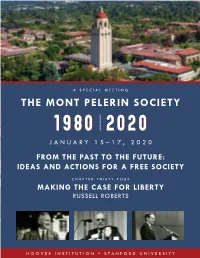

A SPECIAL MEETING THE MONT PELERIN SOCIETY JANUARY 15–17, 2020 FROM THE PAST TO THE FUTURE: IDEAS AND ACTIONS FOR A FREE SOCIETY CHAPTER THIRTY-FOUR MAKING THE CASE FOR LIBERTY RUSSELL ROBERTS HOOVER INSTITUTION • STANFORD UNIVERSITY 1 1 MAKING THE CASE FOR LIBERTY Prepared for the January 2020 Mont Pelerin Society Meeting Hoover Institution, Stanford University Russ Roberts John and Jean De Nault Research Fellow Hoover Institution Stanford University [email protected] 1 2 According to many economists and pundits, we are living under the dominion of Milton Friedman’s free market, neoliberal worldview. Such is the claim of the recent book, The Economists’ Hour by Binyamin Applebaum. He blames the policy prescriptions of free- market economists for slower growth, inequality, and declining life expectancy. The most important figure in this seemingly disastrous intellectual revolution? “Milton Friedman, an elfin libertarian…Friedman offered an appealingly simple answer for the nation’s problems: Government should get out of the way.” A similar judgment is delivered in a recent article in the Boston Review by Suresh Naidu, Dani Rodrik, and Gabriel Zucman: Leading economists such as Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman were among the founders of the Mont Pelerin Society, the influential group of intellectuals whose advocacy of markets and hostility to government intervention proved highly effective in reshaping the policy landscape after 1980. Deregulation, financialization, dismantling of the welfare state, deinstitutionalization of labor markets, reduction in corporate and progressive taxation, and the pursuit of hyper-globalization—the culprits behind rising inequalities—all seem to be rooted in conventional economic doctrines. -

Inspired Comment on the Commentary of The

Comment on the Commentary of the Day by Donald J. Boudreaux Chairman, Department of Economics George Mason University [email protected] http://www.cafehayek.com Disclaimer: The following “Letters to the Editor” were sent to the respective publications on the dates indicated. Some were printed but many were not. The original articles that are being commented on may or may not be available on the internet and may require registration or subscription to access if they are. Some of the original articles are syndicated and therefore may have appeared in other publications also. 20 February 2011 "correspondent Louise centralized state – that Mr. Hidalgo in Kazakhstan Ehrlich advises we must Editor, Los Angeles Times says that the most amazing submit to if we are to be thing about the disaster is saved from genuine eco- Dear Editor: that it is no accident. 'The disasters. Soviet planners who fatally Three different readers tapped the rivers, which 19 February 2011 write today in praise of fed the seas to irrigate Paul Ehrlich and his central Asia's vast cotton Friends, predictions of eco- fields, expected it dry up. mageddon (Letters, Feb. They either did not realise I just discovered this hour- 20). Such praise is odd, the consequences the plus long video of a talk on given that not one of the Aral's disappearance would immigration that my brilliant many catastrophes that Mr. bring or they simply did not young colleague Bryan Ehrlich has predicted over care.'" Caplan delivered, here on the past 43 years has [http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/ GMU's Fairfax campus, occurred. -

Exploring Inequality

SMU McLane/Armentrout/Bridwell Scholars Reading Groups Fall 2020 Syllabus Exploring Inequality Tues./Wed.: Dean Stansel, Ph.D., Senior Research Fellow [email protected], office: 214-768-3492 Mon./Fri.: Meg Tuszynski, Ph.D., Research Fellow & Assistant Director [email protected], office: 214-768-3170 O’Neil Center for Global Markets & Freedom (www.oneilcenter.org) Cox School of Business, Crow 282 Meeting Times. Our meetings will be held on Mondays (Bridwell), Tuesdays (McLane), and Wednesdays (Armentrout) at 6-7 pm (Central time), and Fridays (Armentrout) at 11am-noon (Central time) online via Zoom. All four groups have the same readings. Attendance is required. Your attendance and active participation are required. We will have 10 regular meetings plus a joint reading group summit with the students from similar reading groups at Baylor, Texas Tech, Angelo State, and University of Central Arkansas. That event will be held online via Zoom on the morning of Sat. Oct. 17 and is a required part of the program. You will not be paid the $1000 stipend if you do not attend. You are required to attend all 10 weekly meetings. However, if you have an unavoidable conflict, we do have limited flexibility, with advance notice, for you to switch nights if you cannot attend on your regular reading group night (i.e., if you can’t make one of your regular Monday night meetings, you can instead attend on Tuesday, Wednesday, or Friday that week and vice-versa). In addition, the O’Neil Center hosts several guest speakers throughout the semester. Those will all be online this semester. -

Comment on the Commentary of the Day by Donald J

Comment on the Commentary of the Day by Donald J. Boudreaux Chairman, Department of Economics George Mason University [email protected] http://www.cafehayek.com Disclaimer: The following “Letters to the Editor” were sent to the respective publications on the dates indicated. Some were printed but many were not. The original articles that are being commented on may or may not be available on the internet and may require registration or subscription to access if they are. Some of the original articles are syndicated and therefore may have appeared in other publications also. 5 October 2008 insist that FDR's policies policies "ravaged the cured the economy's ills. requisite confidence." Editor, Washington Post The truth is, as economist [Robert Higgs, 1150 15th St., NW Peter Fearon wrote in "Depression, War, and Washington, DC 20071 1987, that "Perhaps the Cold War" (New York: New Deal's greatest failure Oxford University Press, Dear Editor: lay in its inability to 2006), p. 8] generate the revival in Rep. Rahm Emanuel says private investment that that "FDR inherited a would have led to greater depression and gave output and more jobs." America the greatest [Peter Fearon, "War, expansion of the middle Prosperity and Depression: class it has ever known" The U.S. Economy 1917- (Letters, October 5). This 45" (Lawrence, KS: claim is patently false. University Press of Kansas, 1987), p. 208] Even persons with even Economist Robert Higgs just a passing knowledge adds that "The willingness of history know that the of business people to American economy was in invest requires a depression for all of the sufficiently healthy state of 1930s. -

Download Issue (PDF)

VOLUME 61, NO 10 DECEMBER 2011 Features 8 Unemployment: What’s To Be Done? by Warren C. Gibson 11 Scientism and the Great Power Nexus by Max Borders 17 A Return to Gold? by John A.Allison and John L. Chapman 22 The Family Stone: Cavemen, Trade, and Comparative Advantage by Richard W.Fulmer 27 The Twisted Tree of Progressivism by Joseph R. Stromberg 34 Money Is Not Speech by Michael Cummins 36 The Age of the Busybody by Ridgway Knight Foley, Jr. Page 17 Columns 2 Perspective ~ Elizabeth Warren’s Non Sequitur by Sheldon Richman 4 Ideas and Consequences ~ Wanted:A Healthy Dose of Humility by Lawrence W.Reed 6 Keynesianism Doesn’t Mean Bigger Government? It Just Ain’t So! by Steven Horwitz 15 Our Economic Past ~ The First Government Bailouts: The Story of the RFC by Burton Folsom, Jr. 25 Peripatetics ~ Social Cooperation, Part 2 by Sheldon Richman 32 The Therapeutic State ~ Imprisoning Innocents by Thomas Szasz 40 Give Me a Break! ~ Ten Years After by John Stossel Page 25 47 The Pursuit of Happiness ~ Population Control Nonsense by Walter E.Williams Book Reviews 42 Pearl Harbor: The Seeds and Fruits of Infamy by Percy L. Greaves, Jr., edited by Bettina Bien Greaves Reviewed by Jim Powell 43 Crisis Economics: A Crash Course in the Future of Finance by Nouriel Roubini and Stephen Mihm Reviewed by George Selgin 44 Back on the Road to Serfdom: The Resurgence of Statism edited by Thomas E.Woods, Jr. Reviewed by George Leef 45 The Pursuit of Justice: Law and Economics of Legal Institutions edited by Edward J. -

Holly Martins and the Impartial Spectator: the Economics of the Third Man Alexander W

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Proceedings of the Seventh Annual MadRush MAD-RUSH Undergraduate Research Conference Conference: Best Papers, Spring 2016 Holly Martins and the Impartial Spectator: The Economics of The Third Man Alexander W. Pickens James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.lib.jmu.edu/madrush Part of the Economic History Commons, Economic Theory Commons, and the Other Film and Media Studies Commons Alexander W. Pickens, "Holly Martins and the Impartial Spectator: The cE onomics of The Third Man" (March 28, 2016). MAD-RUSH Undergraduate Research Conference. Paper 1. http://commons.lib.jmu.edu/madrush/2016/EconomicsOfTheEveryday/1 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conference Proceedings at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in MAD-RUSH Undergraduate Research Conference by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 ALEX PICKENS ENG385: Film Noir Paper Three Professor Brooks Hefner Holly Martins and the Impartial Spectator: The Economics of The Third Man The particular malaise that distinguishes film noir as a stylistic articulation makes it unusually mobile in its content. From critiques of gender roles to expressions of societal dysfunction, this ambiguity is inherently fitting for the visuals that have defined it; it would make sense then that one of the most ambiguous areas of study that affects every aspect of society, economics, would produce one of the greatest films in noir: The Third Man. Much talked about for its take on national identity, occupation, post-war depression, and even language, critics have largely overlooked the film’s primary purpose of dwelling on the problematic nature of economic theory such as market structures and allocation of goods. -

Kelly on the Future, Productivity, and the Quality of Life

ECONTALK PERMANENT LINK | JANUARY 21, 2013 Printable format for http://www.econtalk.org/archives/2013/01/kelly_on_the_fu.html Kelly on the Future, Productivity, and the Quality FAQ: Print Hints of Life EconTalk Episode with Kevin Kelly Hosted by Russ Roberts Kevin Kelly talks with EconTalk host Russ Roberts about measuring productivity in the internet age and recent claims that the U.S. economy has entered a prolonged period of stagnation. Then the conversation turns to the potential of robots to change the quality of our daily lives. Play Time: 58:34 How do I listen to a podcast? Download Size: 26.9 MB Rightclick or Optionclick, and select "Save Link/Target As MP3. Readings and Links related to this podcast Podcast Readings HIDE READINGS About this week's guest: Kevin Kelly's Home page About ideas and people mentioned in this podcast: Books: What Technology Wants, by Kevin Kelly at Amazon.com. Articles: "The PostProductive Economy," by Kevin Kelly at the Technium, January 1, 2013. "Better Than Human: Why Robots Willand MustTake Our Jobs," by Kevin Kelly at Wired.com, December 24, 2012. "Is US Economic Growth Over?" by Robert Gordon, Working Paper 18315, NBER, August 2012. Productivity, by Alexander J. Field. Concise Encyclopedia of Economics. Standards of Living and Modern Economic Growth, by John V. C. Nye. Concise Encyclopedia of Economics. Internet, by Stan Liebowitz. Concise Encyclopedia of Economics. Robert Solow. Biography. Concise Encyclopedia of Economics. Thomas Robert Malthus. Biography. Concise Encyclopedia of Economics. Web Pages: Web page for The Squandered Computer, by Paul Strassmann. -

APPLIED MAINLINE ECONOMICS ADVANCED STUDIES in PO LITI CAL ECONOMY Series Editors: Virgil Henry Storr and Stefanie Haefele- Balch

APPLIED MAINLINE ECONOMICS ADVANCED STUDIES IN PO LITI CAL ECONOMY Series Editors: Virgil Henry Storr and Stefanie Haefele- Balch The Advanced Studies in Po liti cal Economy series consists of repub- lished as well as newly commissioned work that seeks to understand the under pinnings of a free society through the foundations of the Austrian, Virginia, and Bloomington schools of po liti cal economy. Through this series, the Mercatus Center at George Mason University aims to further the exploration and discussion of the dynamics of so cial change by making this research available to students and scholars. Nona Martin Storr, Emily Chamlee- Wright, and Virgil Henry Storr, How We Came Back: Voices from Post- Katrina New Orleans Don Lavoie, Rivalry and Central Planning: The Socialist Calculation Debate Reconsidered Don Lavoie, National Economic Planning: What Is Left? Peter J. Boettke, Stefanie Haefele- Balch, and Virgil Henry Storr, eds., Mainline Economics: Six Nobel Lectures in the Tradition of Adam Smith Matthew D. Mitchell and Peter J. Boettke, Applied Mainline Economics: Bridging the Gap between Theory and Public Policy APPLIED MAINLINE ECONOMICS Bridging the Gap between Theory and Public Policy MATTHEW D. MITCHELL AND PETER J. BOETTKE Arlington, Virginia ABOUT THE MERCATUS CENTER The Mercatus Center at George Mason University is the world’s premier university source for market- oriented ideas— bridging the gap between academic ideas and real- world prob lems. A university- based research center, Mercatus advances knowledge about how markets work to improve people’s lives by training grad u ate students, conducting research, and applying economics to ofer solutions to society’s most pressing prob lems. -

The Role of Government in a Free Society

SMU McLane/Armentrout Scholars Reading Groups Fall 2018 Syllabus The Role of Government in a Free Society Dean Stansel, Ph.D., Research Associate Professor O’Neil Center for Global Markets & Freedom (www.oneilcenter.org) Cox School of Business, Crow 282B, office: 214-768-3492, [email protected] Meeting Times. Our meetings will be held on Tuesdays (McLane) and Wednesdays (Armentrout) at 6-8 pm in the O’Neil Center conference room (Crow 282). Both groups have the same readings. Attendance is required. Your attendance and active participation are required. We will have 10 on- campus meetings plus a joint reading group summit with the students from similar reading groups at Baylor, Texas Tech, and University of Central Arkansas. That will be held at SMU on the evening of Fri. Oct. 12 & the morning and early afternoon of Sat. Oct. 13 and is a required part of the program. You will not be paid the $1000 stipend if you do not attend. In addition, the O’Neil Center hosts several guest speakers throughout the semester. Tentative events are listed on the schedule at the end of this syllabus and you will be alerted if more are scheduled. You are required to attend at least one of those events, but are strongly encouraged to attend all of them for which you do not have a class or reading group conflict. You are expected to attend all 10 weekly meetings, but if you have an unavoidable conflict, you can make up for that absence by attending an extra one of these events (beyond the first required one). -

Leadership and Economic Policy Sandra J. Peart, Dean and E

Leadership and Economic Policy Sandra J. Peart, Dean and E. Claiborne Robins Professor Spring 2020 Office Hours: T/Th 9:30 am and by appointment Email: [email protected] (best bet!) In this course, we explore two questions using historical debates on economic policy as our laboratory. First, what is the scope for policy makers and civil servants to lead the economy through cyclical and secular crises and the inevitable ups-and-downs that accompany economic expansion? How much agency should policy makers assume and when are unusual mechanisms called for? Second, what leadership roles do economists legitimately play in the development and implementation of economic policy? I will frame our discussions generally using the contrast between J. M. Keynes and Friedrich Hayek. One question will be whether this framing fits current debates and the split between Democrats and Republicans in the US. While the ideas of Keynes and Hayek will loom large in the historical context, our focus for contemporary issues is on policy as opposed to personalities. In both his written work and by example throughout his professional life, J. M. Keynes would argue for a significant role of economists as leaders. He acknowledged however that the influence of economists might overleap its usefulness. His General Theory famously closed with this passage: 1 The ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood. Indeed the world is ruled by little else. Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influence, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. -

Top 100 Economics Blogs of 2020 INTELLIGENT ECONOMIST

6/17/2020 Top 100 Economics Blogs Of 2020 | Intelligent Economist INTELLIGENT ECONOMIST Economic Theory & News Menu NEWS Top 100 Economics Blogs of 2020 Written by Prateek Agarwal on June 15, 2020 Welcome, and thank you for joining us for the 5th annual Top Economics Blogs list! We are happy, once again, to introduce you to a freshly updated list of economics blogs for 2020. As always, our winners list provides blogs for many different audiences, ranging from the budding economic enthusiast to the seasoned academic. The list also covers a variety of economics topics, whether it be traditional economic theory or the application of economics to current events and issues. In this meticulously curated list, we’ve condensed the most unique elements of each blog into short descriptions, so that you can see which ones catch your eye. For 2020, a few newcomers have emerged, while many mainstays from 2019 and years before are present as well. Like previous years, we’ve done our best to capture the blogs which stand out for their quality rather than their popularity. As such, the list is an eclectic group that represents a wide range of tastes and perspectives. Regardless of your school of thought or political affiliation, you can find valuable new content in this list of engaging, high-quality economics blogs. Blogs Added in 2020: https://www.intelligenteconomist.com/economics-blogs/ 1/53 6/17/2020 Top 100 Economics Blogs Of 2020 | Intelligent Economist Critical Macro Finance The Demand Side Byte Size Story The one-handed economist the Blog Papers of Dr. -

George Steven Swan, the Law and Economics of Fiduciary Duty

Swan 7-16-12 (Do Not Delete) 7/16/2012 10:52 AM OKLAHOMA CITY UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW VOLUME 37 SPRING 2012 NUMBER 1 ARTICLE THE LAW AND ECONOMICS OF FIDUCIARY DUTY: WOMACK V. ORCHIDS PAPER PRODUCTS CO. 401(k) SAVINGS PLAN George Steven Swan, S.J.D.* I. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................... 19 II. THE PRE-2007 GREAT MODERATION ................................................ 21 A. What Was the Great Moderation? .......................................... 21 B. Did the Great Moderation Mislead? ...................................... 22 III. THE ECONOMICS IN LAW AND ECONOMICS .................................... 25 A. The Paradigm Idea ................................................................. 25 B. Macroeconomics ..................................................................... 29 1. Macroeconomists and Mathematization .......................... 29 2. Macroeconomists, Mathematization, and Modeling ........ 36 3. Macroeconomics, the Business Cycle, and the Evidence .......................................................................... 40 C. Microeconomics ..................................................................... 44 IV. SOCIAL CAPITAL AND FIDUCIARY DUTY ......................................... 49 A. Trust as Social Capital ........................................................... 49 * Certified Financial Planner™; Associate Professor, School of Business and Economics, North Carolina A&T State University; B.A., Ohio State University; J.D., University of Notre