Abdominal Injuries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bariatric Surgery in Adolescents: to Do Or Not to Do?

children Review Bariatric Surgery in Adolescents: To Do or Not to Do? Valeria Calcaterra 1,2 , Hellas Cena 3,4 , Gloria Pelizzo 5,*, Debora Porri 3,4 , Corrado Regalbuto 6, Federica Vinci 6, Francesca Destro 5, Elettra Vestri 5, Elvira Verduci 2,7 , Alessandra Bosetti 2, Gianvincenzo Zuccotti 2,8 and Fatima Cody Stanford 9 1 Pediatric and Adolescent Unit, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Pavia, 27100 Pavia, Italy; [email protected] 2 Pediatric Department, “V. Buzzi” Children’s Hospital, 20154 Milan, Italy; [email protected] (E.V.); [email protected] (A.B.); [email protected] (G.Z.) 3 Clinical Nutrition and Dietetics Service, Unit of Internal Medicine and Endocrinology, ICS Maugeri IRCCS, 27100 Pavia, Italy; [email protected] (H.C.); [email protected] (D.P.) 4 Laboratory of Dietetics and Clinical Nutrition, Department of Public Health, Experimental and Forensic Medicine, University of Pavia, 27100 Pavia, Italy 5 Pediatric Surgery Department, “V. Buzzi” Children’s Hospital, 20154 Milan, Italy; [email protected] (F.D.); [email protected] (E.V.) 6 Pediatric Unit, Fond. IRCCS Policlinico S. Matteo and University of Pavia, 27100 Pavia, Italy; [email protected] (C.R.); [email protected] (F.V.) 7 Department of Health Sciences, University of Milan, 20146 Milan, Italy 8 “L. Sacco” Department of Biomedical and Clinical Science, University of Milan, 20146 Milan, Italy 9 Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02114, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Pediatric obesity is a multifaceted disease that can impact physical and mental health. -

The Subperitoneal Space and Peritoneal Cavity: Basic Concepts Harpreet K

ª The Author(s) 2015. This article is published with Abdom Imaging (2015) 40:2710–2722 Abdominal open access at Springerlink.com DOI: 10.1007/s00261-015-0429-5 Published online: 26 May 2015 Imaging The subperitoneal space and peritoneal cavity: basic concepts Harpreet K. Pannu,1 Michael Oliphant2 1Department of Radiology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 1275 York Avenue, New York, NY 10065, USA 2Department of Radiology, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC, USA Abstract The peritoneum is analogous to the pleura which has a visceral layer covering lung and a parietal layer lining the The subperitoneal space and peritoneal cavity are two thoracic cavity. Similar to the pleural cavity, the peri- mutually exclusive spaces that are separated by the toneal cavity is visualized on imaging if it is abnormally peritoneum. Each is a single continuous space with in- distended by fluid, gas, or masses. terconnected regions. Disease can spread either within the subperitoneal space or within the peritoneal cavity to Location of the abdominal and pelvic organs distant sites in the abdomen and pelvis via these inter- connecting pathways. Disease can also cross the peri- There are two spaces in the abdomen and pelvis, the toneum to spread from the subperitoneal space to the peritoneal cavity (a potential space) and the subperi- peritoneal cavity or vice versa. toneal space, and these are separated by the peritoneum (Fig. 1). Regardless of the complexity of development in Key words: Subperitoneal space—Peritoneal the embryo, the subperitoneal space and the peritoneal cavity—Anatomy cavity remain separated from each other, and each re- mains a single continuous space (Figs. -

Small Bowel Obstruction After Laparoscopic Roux-En-Y Gastric Bypass Presenting As Acute Pancreatitis: a Case Report

Netherlands Journal of Critical Care Submitted January 2018; Accepted April 2018 CASE REPORT Small bowel obstruction after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass presenting as acute pancreatitis: a case report N. Henning1, R.K. Linskens2, E.E.M. Schepers-van der Sterren3, B. Speelberg1 Department of 1Intensive Care, 2Gastroenterology and Hepatology, and 3Surgery, Sint Anna Hospital, Geldrop, the Netherlands. Correspondence N. Henning - [email protected] Keywords - Roux-en-Y, gastric bypass, pancreatitis, pancreatic enzymes, small bowel obstruction, biliopancreatic limb obstruction. Abstract Small bowel obstruction is a common and potentially life-threatening bowel obstruction within this complication after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. population, because misdiagnosis We describe a 30-year-old woman who previously underwent can have disastrous outcomes.[1,3-5,7] gastric bypass surgery. She was admitted to the emergency In this report we describe the department with epigastric pain and elevated serum lipase levels. difficulty of diagnosing small Conservative treatment was started for acute pancreatitis, but she bowel obstruction in post- showed rapid clinical deterioration due to uncontrollable pain and LRYGB patients and why frequent excessive vomiting. An abdominal computed tomography elevated pancreatic enzymes scan revealed small bowel obstruction and surgeons performed can indicate an obstruction in an exploratory laparotomy with adhesiolysis. Our patient quickly these patients. The purpose of improved after surgery and could be discharged home. This case this manuscript is to emphasise report emphasises that in post-bypass patients with elevated Figure 1. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass that in post-bypass patients with pancreatic enzymes, small bowel obstruction should be considered ©Ethicon, Inc. -

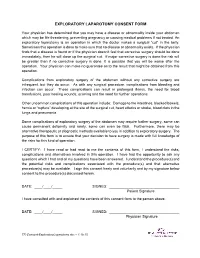

Exploratory Laparotomy.Docx

EXPLORATORY LAPAROTOMY CONSENT FORM Your physician has determined that you may have a disease or abnormality inside your abdomen which may be life threatening, preventing pregnancy or causing medical problems if not treated. An exploratory laparotomy is an operation in which the doctor makes a surgical “cut” in the belly. Sometimes this operation is done to make sure that no disease or abnormality exists. If the physician finds that a disease is found or if the physician doesn’t feel that corrective surgery should be done immediately, then he will close up the surgical cut. If major corrective surgery is done the risk will be greater than if no corrective surgery is done. It is possible that you will be worse after the operation. Your physician can make no guarantee as to the result that might be obtained from this operation. Complications from exploratory surgery of the abdomen without any corrective surgery are infrequent, but they do occur. As with any surgical procedure, complications from bleeding and infection can occur. These complications can result in prolonged illness, the need for blood transfusions, poor healing wounds, scarring and the need for further operations. Other uncommon complications of this operation include: Damage to the intestines, blocked bowels, hernia or “rupture” developing at the site of the surgical cut, heart attacks or stroke, blood clots in the lungs and pneumonia. Some complications of exploratory surgery of the abdomen may require further surgery, some can cause permanent deformity and rarely, some can even be fatal. Furthermore, there may be alternative therapeutic or diagnostic methods available to you in addition to exploratory surgery. -

Magnetic Resonance Enterography Findings of a Gastrocolic Fistula in Crohn’S Disease

Letter to the Editor Magnetic resonance enterography findings of a gastrocolic fistula in Crohn’s disease Sanne N. van Munster1, Mark F. J. Stolk2, Karel C. Kuypers3, Rene Wiezer1, Thomas L. Bollen4 1Department of Surgery, 2Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 3Department of Pathology, 4Department of Radiology, Sint Antonius Ziekenhuis, Nieuwegein, The Netherlands Correspondence to: Drs. Sanne N. van Munster. AMC, Academisch Medisch Centrum Amsterdam, Meibergdreef 9, 1105 AZ Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Email: [email protected]. Submitted Jul 09, 2016. Accepted for publication Jul 30, 2016. doi: 10.21037/qims.2016.08.06 View this article at: http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/qims.2016.08.06 Crohn’s disease (CD) is characterized by patches of Definitive treatment was established by segment inflammation, which may affect the whole gastro-intestinal resection of the splenic flexure with stapling of the tract. Internal fistulization is a common complication of CD gastrocolic fistula Figure( 1). The postoperative course was due to the transmural nature of inflammation. However, unremarkable and patient recovered uneventfully. gastrocolic fistulas are rare in CD. We present the magnetic Gross pathological examination of the surgical specimen resonance enterography (MRE) findings of a gastrocolic confirmed the presence of fistulous disease. A deep fistula in a patient with longstanding CD with clinical and penetrating inflammatory process originated from the pathologic correlation. colonic mucosa, extended through the colonic wall and attached to the stomach. In this inflammatory tract, gastric mucosa was found represented by glands formed by parietal Case presentation and chief cells of fundic mucosa. A 29-year-old woman with perianal fistulizing CD visited our hospital for left-sided upper abdominal pain starting Discussion about 30 minutes after the meals, bloating, diarrhea, anorexia, and weight loss. -

Abdominal Exploratory and Closure

Abdominal exploratory and closure 10.1 Diagnostic procedures 10.1.1 Paracentesis 10.1.1.1 Paracentesis technique 10.1.2 Enterocentesis 10.1.2.1 Enterocentesis technique 10.2 Opening of the abdominal cavity 10.2.1 Introduction 10.2.2 Position of the animal 10.2.3 Location of incision 10.2.4 Type of incision 10.2.4.1 Through-and-through incision 10.2.4.2 Complete grid Incision 10.2.4.3 Partial grid incision 10.2.5 Laparotomy in the bovine 10.2.5.1 Indications 10.2.5.2 Through-and-through incision 10.2.5.3 Partial grid incision 10.2.5.4 Complete grid incision 10.2.6 Laparotomy in small ruminants Chapter 10 10.2.7 Laparotomy in the horse 10.2.7.1 Indications 10.2.7.2 The median coeliotomy 10.2.7.3 The paramedian laparotomy 10.2.8 Coeliotomy in the dog and the cat 10.2.8.1 Indications 10.2.8.2 The median coeliotomy 10.2.8.3 The flank or paracostal incision 10.3 Minimally invasive techniques 10.4 Abdominal procedures 10.4.1 The rumen (bovine, small ruminants) 10.4.1.1 Introduction 10.4.1.2 Rumenotomy 10.4.2 The abomasum (bovine) 10.4.3 The stomach (horse, dog and cat) 10.4.3.1 Introduction 10.4.3.2 Gastrotomy in the dog and the cat 10.4.4 The small- and large intestines 10.4.4.1 Introduction 10.4.4.1.1 Simple mechanical ileus 10.4.4.1.2 Strangulating ileus 10.4.4.1.3 Paralytic ileus 10.4.4.2 Diagnostics 10.4.4.3 Therapy 10.4.4.3.1 Enterotomy 10.4.4.3.2 Enterectomy 10.4.5 The bladder 10.4.5.1 Introduction 10.4.5.2 Urolithiasis in bovine and equine 10.4.5.3 Cystotomy in the horse 10.4.5.3.1 Laparocystotomy 10.4.5.3.2 Pararectal cystotomy 10.4.5.4 Urolithiasis in the dog and the cat 10.4.5.5 Cystotomy in the dog and the cat 10.4.6 The uterus 10.4.6.1 Opening and closing of the uterus 10.4.6.2 Ovariectomy and ovariohysterectomy in dog and cat Chapter 10 176 Chapter 10 Abdominal exploratory and closure 10.1 Diagnostic procedures 10.1.1 Paracentesis paracentesis Paracentesis is the puncturing of the abdominal cavity. -

Parts of the Body 1) Head – Caput, Capitus 2) Skull- Cranium Cephalic- Toward the Skull Caudal- Toward the Tail Rostral- Toward the Nose 3) Collum (Pl

BIO 3330 Advanced Human Cadaver Anatomy Instructor: Dr. Jeff Simpson Department of Biology Metropolitan State College of Denver 1 PARTS OF THE BODY 1) HEAD – CAPUT, CAPITUS 2) SKULL- CRANIUM CEPHALIC- TOWARD THE SKULL CAUDAL- TOWARD THE TAIL ROSTRAL- TOWARD THE NOSE 3) COLLUM (PL. COLLI), CERVIX 4) TRUNK- THORAX, CHEST 5) ABDOMEN- AREA BETWEEN THE DIAPHRAGM AND THE HIP BONES 6) PELVIS- AREA BETWEEN OS COXAS EXTREMITIES -UPPER 1) SHOULDER GIRDLE - SCAPULA, CLAVICLE 2) BRACHIUM - ARM 3) ANTEBRACHIUM -FOREARM 4) CUBITAL FOSSA 6) METACARPALS 7) PHALANGES 2 Lower Extremities Pelvis Os Coxae (2) Inominant Bones Sacrum Coccyx Terms of Position and Direction Anatomical Position Body Erect, head, eyes and toes facing forward. Limbs at side, palms facing forward Anterior-ventral Posterior-dorsal Superficial Deep Internal/external Vertical & horizontal- refer to the body in the standing position Lateral/ medial Superior/inferior Ipsilateral Contralateral Planes of the Body Median-cuts the body into left and right halves Sagittal- parallel to median Frontal (Coronal)- divides the body into front and back halves 3 Horizontal(transverse)- cuts the body into upper and lower portions Positions of the Body Proximal Distal Limbs Radial Ulnar Tibial Fibular Foot Dorsum Plantar Hallicus HAND Dorsum- back of hand Palmar (volar)- palm side Pollicus Index finger Middle finger Ring finger Pinky finger TERMS OF MOVEMENT 1) FLEXION: DECREASE ANGLE BETWEEN TWO BONES OF A JOINT 2) EXTENSION: INCREASE ANGLE BETWEEN TWO BONES OF A JOINT 3) ADDUCTION: TOWARDS MIDLINE -

Greater Omentum Connects the Greater Curvature of the Stomach to the Transverse Colon

Dr. ALSHIKH YOUSSEF Haiyan General features The peritoneum is a thin serous membrane Consisting of: 1- Parietal peritoneum -lines the ant. Abdominal wall and the pelvis 2- Visceral peritoneum - covers the viscera 3- Peritoneal cavity - the potential space between the parietal and visceral layer of peritoneum - in male, is a closed sac - but in the female, there is a communication with the exterior through the uterine tubes, the uterus, and the vagina ▪ Peritoneum cavity divided into Greater sac Lesser sac Communication between them by the epiploic foramen The peritoneum The peritoneal cavity is the largest one in the body. Divided into tow sac : .Greater sac; extends from diaphragm down to the pelvis. Lesser Sac .Lesser sac or omental bursa; lies behind the stomach. .Both cavities are interconnected through the epiploic foramen(winslow ). .In male : the peritoneum is a closed sac . .In female : the sac is not completely closed because it Greater Sac communicates with the exterior through the uterine tubes, uterus and vagina. Peritoneum in transverse section The relationship between viscera and peritoneum Intraperitoneal viscera viscera is almost totally covered with visceral peritoneum example, stomach, 1st & last inch of duodenum, jejunum, ileum, cecum, vermiform appendix, transverse and sigmoid colons, spleen and ovary Intraperitoneal viscera Interperitoneal viscera Retroperitoneal viscera Interperitoneal viscera Such organs are not completely wrapped by peritoneum one surface attached to the abdominal walls or other organs. Example liver, gallbladder, urinary bladder and uterus Upper part of the rectum, Ascending and Descending colon Retroperitoneal viscera some organs lie on the posterior abdominal wall Behind the peritoneum they are partially covered by peritoneum on their anterior surfaces only Example kidney, suprarenal gland, pancreas, upper 3rd of rectum duodenum, and ureter, aorta and I.V.C The Peritoneal Reflection The peritoneal reflection include: omentum, mesenteries, ligaments, folds, recesses, pouches and fossae. -

ABDOMINOPELVIC CAVITY and PERITONEUM Dr

ABDOMINOPELVIC CAVITY AND PERITONEUM Dr. Milton M. Sholley SUGGESTED READING: Essential Clinical Anatomy 3 rd ed. (ECA): pp. 118 and 135141 Grant's Atlas Figures listed at the end of this syllabus. OBJECTIVES:Today's lectures are designed to explain the orientation of the abdominopelvic viscera, the peritoneal cavity, and the mesenteries. LECTURE OUTLINE PART 1 I. The abdominopelvic cavity contains the organs of the digestive system, except for the oral cavity, salivary glands, pharynx, and thoracic portion of the esophagus. It also contains major systemic blood vessels (aorta and inferior vena cava), parts of the urinary system, and parts of the reproductive system. A. The space within the abdominopelvic cavity is divided into two contiguous portions: 1. Abdominal portion that portion between the thoracic diaphragm and the pelvic brim a. The lower part of the abdominal portion is also known as the false pelvis, which is the part of the pelvis between the two iliac wings and above the pelvic brim. Sagittal section drawing Frontal section drawing 2. Pelvic portion that portion between the pelvic brim and the pelvic diaphragm a. The pelvic portion of the abdominopelvic cavity is also known as the true pelvis. B. Walls of the abdominopelvic cavity include: 1. The thoracic diaphragm (or just “diaphragm”) located superiorly and posterosuperiorly (recall the domeshape of the diaphragm) 2. The lower ribs located anterolaterally and posterolaterally 3. The posterior abdominal wall located posteriorly below the ribs and above the false pelvis and formed by the lumbar vertebrae along the posterior midline and by the quadratus lumborum and psoas major muscles on either side 4. -

Exploratory Laparotomy Following Penetrating Abdominal Injuries: a Cohort Study from a Referral Hospital in Erbil, Kurdistan Region in Iraq

Exploratory laparotomy following penetrating abdominal injuries: a cohort study from a referral hospital in Erbil, Kurdistan region in Iraq Research protocol 1 November 2017 FINAL version Table of Contents Protocol Details .............................................................................................................. 3 Signatures of all Investigators Involved in the Study .................................................... 4 Summary ........................................................................................................................ 5 List of Abbreviations ..................................................................................................... 6 List of Definitions .......................................................................................................... 7 Background .................................................................................................................... 8 Justification .................................................................................................................... 9 Aim of Study .................................................................................................................. 9 Investigation Plan ......................................................................................................... 10 Study Population .......................................................................................................... 10 Data ............................................................................................................................. -

Digestive Endoscopy in Five Decades

■ COLLEGE LECTURES Digestive endoscopy in five decades Peter B Cotton ABSTRACT – The world of gastroenterology scopy. So-called semi-flexible gastroscopes were changed forever when flexible endoscopes cumbersome and used infrequently by only a few became available in the 1960s. Diagnostic and enthusiasts. therapeutic techniques proliferated and entered the mainstream of medicine, not without some Diagnostic endoscopy controversy. Success resulted in a huge service demand, with the need to train more endo- The first truly flexible gastroscope was developed in 1 This paper is scopists and to organise large endoscopy units the USA, following pioneering work on fibre-optic 2 based on the Lilly and teams of staff. The British health service light transmission in the UK by Harold Hopkins. Lecture given at struggled with insufficient numbers of consul- However, commercial production of endoscopes was the Royal College tants, other staff and resources, and British rapidly dominated by Japanese companies, building of Physicians on endoscopy fell behind that of most other devel- on their earlier expertise with intragastric cameras. 12 April 2005 by oped countries. This situation is now being My involvement began in 1968, whilst doing bench Peter B Cotton addressed aggressively, with many local and research with Dr Brian Creamer at St Thomas’ MD FRCP FRCS, national initiatives aimed at improving access and Hospital, London. An expert in coeliac disease (and Medical Director, choice, and at promoting and documenting jejunal biopsy), he opined that gastroscopy might Digestive Disease quality. Many more consultants are needed and become useful and legitimate only if it became pos- Center, Medical some should be relieved of their internal medi- sible to take target biopsy specimens – since no one University of South Carolina, cine commitment to focus on their specialist seriously believed what endoscopists said that they Charleston, USA skills. -

Duodenal Perforation Caused by Eyeglass Temples: a Case Report

Case Report Annals of Clinical Case Reports Published: 27 Jan, 2020 Duodenal Perforation Caused by Eyeglass Temples: A Case Report Zhiyong Dong1#, Wenhui Chen1#, Jin Gong1, Juncan Zhang1, Hina Mohsin2 and Cunchuan Wang1* 1Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, The First Affiliated Hospital of Jinan University, China 2Department of Neurology, California University of Science and Medicine, USA #These authors contributed equally to this work Abstract Background: While some foreign bodies in the digestive system can be egested spontaneously or after ingesting lubricants, generally long, large, sharp, irregularly shaped, hardened and/or toxic foreign bodies frequently remain in the digestive system. These foreign bodies may cause obstruction or damage the gastrointestinal mucosa leading to bleeding, perforation, and/or acute peritonitis, and may even cause local abscess, fistula formation, or organ damage. Case Report: A 30-year-old Chinese man was presented with acute abdominal pain while intoxicated with alcohol and swallowed two eyeglass temples. Conservative measures including ingesting lubricants to egest the foreign bodies failed. He underwent two exploratory laparotomy that showed a duodenal perforation and eventually the two eyeglass temples retrieved. Conclusion: This is the first report describing a patient who had swallowed eyeglass temples. Patients who swallow such objects must be promptly examined and diagnosed by ultrasound, X-ray, and/or CT, and foreign bodies removed by laparoscopy or laparotomy. Keywords: Duodenal perforation; Foreign body; Exploratory laparotomy OPEN ACCESS Introduction *Correspondence: Cunchuan Wang, Department of The effects of foreign bodies in the digestive system depend on their texture, shape, size, toxicity, Gastrointestinal Surgery, The First retention site, and duration [1]. Report of foreign bodies includes dentures, glass beads, coins, pens, Affiliated Hospital of Jinan University, fish bones [2].