Forest Lanterns.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Admitted Lok Sabha Pq. Starred Un-Starred

ADMITTED LOK SABHA PQ. Dtd.03.02.2021 STARRED Commercial Coal Mining *22. SHRI JAYANT SINHA: (a) the key benefits of commercial coal mining policy; (b) the amount of revenue generated from such exercises as on date; (c) the share received by Jharkhand in such revenue; and (d) the details of coal mines auctioned in Jharkhand under the said policy, district-wise? Opening of new Coal Mines *35. DR. SANJEEV KUMAR SINGARI: Will the Minister of COAL be pleased to state: (a) whether the Government is planning to open new coal mines; (b) if so, the details of the proposed number of new coal mines and the proposed sites of mining; (c) whether the Government is planning to use forest lands for the proposed new mines and if so, the details of place and number of hectares of forest land to be used in case of each new mine; and (d) the percentage of energy needs of India that are achieved through coal mining? ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- UN-STARRED Coal Auction 238. SHRI BALUBHAU ALIAS SURESH NARAYAN DHANORKAR: (a) whether Government has decided to auction new coal and mineral blocks in the country? (b) if so, the details thereof, State-wise including Maharashtra? (c) the details of modifications made in the revenue sharing mechanism in the coal sector; and (d) the steps taken by the Government to minimise the import of coal from other countries? Commercial Coal Mining 253. SHRI BIDYUT BARAN MAHATO: SHRI RAVI KISHAN: SHRI SUBRAT PATHAK: SHRI CHANDRA -

2019 Mahatma Phule Krishi Vidyapeeth

Annual Report 2015 - 2016 ANNUAL REPORT 2015 - 2016 Editorial Board MAHATMA PHULE KRISHI VIDYAPEETH Chairman Rahuri - 413: Dr. 722, Sharad Dist. Gadakh Ahmednagar (Maharashtra) Directorwww.mpkv.ac.in of Extension Education Mahatma Phule Krishi Vidyapeeth, Rahuri Members : Dr. Ashok Pharande Dean, Faculty of Agriculture Dr. Sharad Gadakh Director of Research Er. Vijay Kote Comptroller Er. Milind Dhoke University Engineer Compiled by : Dr. Pandit Kharde, Officer Incharge, Communication Centre Dr. Sachin Sadaphal, Assistant Professor, Communication Centre Dr. Sangram Kale, Assistant Professor, Directorate of Research Shri. Adinath Andhale, SRA, Office of Dean, F/A Shri. Sunil Rajmane, Agri. Assistant, Communication Centre Publisher : Shri. Mohan Wagh Registrar, Mahatma Phule Krishi Vidyapeeth, Rahuri, Dist. Ahmednagar, Maharashtra (India) MPKV / Extn. Pub./ No. 2353/ 2020 Annual Report 2018- 2019 Annual Report 2015 - 2016 ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL2018 - REPORT2019 2015 - 2016 Annual Report 2015 - 2016 ANNUAL REPORT 2015 - 2016 MAHATMAMAHATMA PHULE PHULE KRISHI VIDYAPEETH VIDYAPEETH RahuriRahuri - -413 413 722, 722, Dist.Dist. Ahmednagar (Maharashtra) (Maharashtra) www.mpkv.ac.in www.mpkv.ac.in MAHATMA PHULE KRISHI VIDYAPEETH Rahuri - 413 722, Dist. Ahmednagar (Maharashtra) www.mpkv.ac.in Annual Report 2018- 2019 Annual Report 2015 - 2016 ANNUAL REPORT 2015 - 2016 MAHATMA PHULE KRISHI VIDYAPEETH Rahuri - 413 722, Dist. Ahmednagar (Maharashtra) www.mpkv.ac.in Annual Report 2018- 2019 Annual Report 2015 - 2016 Dr. K. P. Viswanatha Vice Chancellor, -

![DY`Exf ¶D Hzwv Gd CR[ Rey ]Z\V]J](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1896/dy-exf-%C2%B6d-hzwv-gd-cr-rey-z-v-j-651896.webp)

DY`Exf ¶D Hzwv Gd CR[ Rey ]Z\V]J

% RNI Regn. No. MPENG/2004/13703, Regd. No. L-2/BPLON/41/2006-2008 )1$9)-@ABC &'((& ) *&+, -- .(./$(01 -2 ) '$ ('>) !$(>7#)>% (1>'7('#(9 1 9$9#!7>8 :$>(9:$#:(7 8( (7!$(# !$(71($ '$ >:9 !>9>7 >@ : A' 8(?'>'(?!>>9 1 $(1#7 $?1 (:(1@.(?8(1( ! +4;3 ))6 BC D( ( & 5 ( 5D@EF@GC@4D !" # $% $&& '($# R ! " 7 81 9$ ))#*+, #-$# 7 81 9$ -.+*"$*)")0*1,+" reaking his silence after he Samajwadi Party is like- Bfive long years, BJP patri- -")1$#-,"-+.+, Tly to line up an interesting arch LK Advani on Thursday 0"))+#4%1,"+. challenge for the BJP by field- penned a blog saying the 1)#*01+#51 ing “Bihari Babu” Shatrughan essence of Indian democracy is Sinha’s wife Poonam Sinha respect for diversity and free- $)#""%$"-- against Union Home Minister dom of expression and that the 1+)+-)$%"1 Rajnath Singh from Lucknow, 7 %+ + BJP never regarded those who 6)0+1*$$)+6" a prestigious Lok Sabha seat # :.' disagree with the party politi- also held by party’s patriarch cally as its “enemies” and “anti- M#.)N5961+#$) late AB Vajpayee in the past. ;&<=+ nationals.” +6"$-")$") This came on a day BJP #O ! While the blog remains L -$# brought in Nishad Party to the focused on highlighting the BJP NDA fold in Uttar Pradesh ! core commitment and Advani’s where it faces a tough faceoff 9 + personal journey, the BJP vet- -$#;0",*1)6.)60 to the people of Gandhinagar”, with the SP-BSP-RLD alliance. ) ! %' (: + eran has tried to show mirror 11"6))#*+, 5.+)1 who have elected him to the Praveen Nishad, the MP :.' to many of the party leaders #+1$91%6-#%.$#1"$+, Lok Sabha six times since from Gorakhpur and the giant who have been quick to tag as O $1+#,")150$"1#15), 1991. -

No. of Questions : 40 Full Mark : 40 Time : 20 Min Correct : ___

WEEKLY CURRENT AFFAIRS QUESTION DISCUSSION – 26.05.2019 TO 02.06.2019 No. of Questions : 40 Correct : ____________ Full Mark : 40 Wrong : _____________ Time : 20 min Mark Secured : _______ 1. India’s first Tree Ambulance was inaugurated recently at which place? A)Chennai B) Kolkata C) Bengaluru D) Mumbai 2. Prime Minister, Peter O’Neill of which country resigned recently? A) Papua New Guinea B) Thailand C) Singapore D) New Zealand 3. Which organization has recognized ‘burn-out’ as medical condition and ‘gaming disorder’ as illness? A) WHO B) United Nations C) UNESCO D) UNICEF 4. Abhay Kumar has been appointed as the Ambassador of India to which country? A) Spain B) Nigeria C) Comoros D) Madagascar 5. Prem Tinsulanonda, Former prime minister & royal confidante of which country passed away at the age of 98 recently? A) Philippines B) Vietnam C) Thailand D) Cambodia 6. Which two organisations has been merged to form National Statistical Office(NSO) under MOSPI? i) Central Statistical Office ii) National Sample Survey Organisation iii) National Statistical Organisation A)Option i & ii B) Option i & iii C) Option ii & iii D) None of these 7. Who has been sworn in as the 6th CM of Sikkim? A) Pawan Kumar Chamling B) Prem Singh Tamang C) Nar Bahadur Bhandari D) None of these 8. Which country launched the world’s largest nuclear-powered icebreaker named ‘Ural’? A) India B) Russia C) China D) Japan 9. Name the cryptocurrency, which is set to be launched by Facebook in 2020? A) Petro B) Bitcoin C) GlobalCoin D) Sovereign 10. -

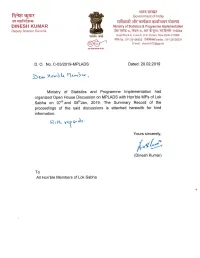

Open House Discussion on MPLAD Scheme with Hon’Ble Members of Lok Sabha

Ministry of Statistics & PISummary Record of Proceedings of Open House Discussion on MPLAD Scheme with Hon’ble Members of Lok Sabha Venue, MP: 07th and 08th January, 2019 at Auditorium, 2nd Floor, New Extension Building, Parliament House Annexe, New Delhi 1. Open house discussion on MPLAD Scheme with Hon’ble Members of Lok Sabha was convened on 7th and 08th January, 2019 at the Auditorium, 2nd Floor, New Extension Building, Parliament House Annexe, New Delhi on the initiative of Shri Vijay Goel, Hon’ble MoS for Statistics and Programme Implementation. Shri Pravin Srivastava, Secretary, M/o Statistics and Programme Implementation and Shri Dinesh Kumar, Deputy Director General (PI) were also present. The list of Members invited for the discussions was divided into two groups. On 7th January, 2019, Members from the States of Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra, West Bengal and Gujarat were invited while the Members from the remaining States were invited on 08th Jan, 2019. The list of Hon’ble Members who participated in the discussions is attached as Annex-I. 2. Secretary, MOSPI welcomed and apprised the Hon’ble Members that this discussion is first of its kind for Lok Sabha Members of Parliament. He emphasized that the free flow of ideas and suggestions of Hon’ble Members during the discussions help the Ministry richer in making the Scheme better and shall serve as template for the successors. Secretary requested Hon’ble MOS to open the floor for discussion and invite suggestions for improvement. Address by Hon’ble MoS 3. Hon’ble MoS welcomed the Hon’ble Members and underscored that a discussion of this kind for MPLAD Scheme was being held for the first time for Lok Sabha Members. -

Operational Nuclear Power Plants

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA DEPARTMENT OF ATOMIC ENERGY LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 4668 TO BE ANSWERED ON 24.03.2021 OPERATIONAL NUCLEAR POWER PLANTS 4668. DR. SUJAY RADHAKRISHNA VIKHE PATIL: DR. SHRIKANT EKNATH SHINDE: SHRI DHAIRYASHEEL SAMBHAJIRAO MANE: SHRI UNMESH BHAIYYASAHEB PATIL: DR. HEENA GAVIT: Will the PRIME MINISTER be pleased to state: (a) the total number of Nuclear Power Plants/reactors operating as on date, State-wise along with the quantum of energy produced by each plant/reactor; (b) the total number of new nuclear power stations / reactors proposed to be set up, State-wise along with the total quantum of power likely to be produced from these proposed new nuclear power stations/reactors; (c) the funds earmarked and allocated for these new projects during the current year and the time by which the power production is proposed to commence and commercialised by these plants/reactors; (d) whether the nuclear reactors set up in the country are safe according to the international nuclear standard; and (e) if so, the details thereof along with the frequency of security tests conducted in nuclear reactors and the authority responsible for such tests? ANSWER THE MINISTER OF STATE FOR PERSONNEL, PUBLIC GRIEVANCES & PENSIONS AND PRIME MINISTER’S OFFICE (Dr. JITENDRA SINGH): (a) The details are given in Annexure – A. (b)&(c) The details are given in Annexure - B. (d) Yes, Sir. 1 (e) All the nuclear power reactors are designed in accordance with the codes and guides of the regulatory authority i.e. Atomic Energy Regulatory Board (AERB), which are in line with the International Standards. -

The Journal of Parliamentary Information ______VOLUME LXVI NO.1 MARCH 2020 ______

The Journal of Parliamentary Information ________________________________________________________ VOLUME LXVI NO.1 MARCH 2020 ________________________________________________________ LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI ___________________________________ The Journal of Parliamentary Information VOLUME LXVI NO.1 MARCH 2020 CONTENTS PARLIAMENTARY EVENTS AND ACTIVITIES PROCEDURAL MATTERS PARLIAMENTARY AND CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENTS DOCUMENTS OF CONSTITUTIONAL AND PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST SESSIONAL REVIEW Lok Sabha Rajya Sabha State Legislatures RECENT LITERATURE OF PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST APPENDICES I. Statement showing the work transacted during the Second Session of the Seventeenth Lok Sabha II. Statement showing the work transacted during the 250th Session of the Rajya Sabha III. Statement showing the activities of the Legislatures of the States and Union Territories during the period 1 October to 31 December 2019 IV. List of Bills passed by the Houses of Parliament and assented to by the President during the period 1 October to 31 December 2019 V. List of Bills passed by the Legislatures of the States and the Union Territories during the period 1 October to 31 December 2019 VI. Ordinances promulgated by the Union and State Governments during the period 1 October to 31 December 2019 VII. Party Position in the Lok Sabha, Rajya Sabha and the Legislatures of the States and the Union Territories PARLIAMENTARY EVENTS AND ACTIVITES ______________________________________________________________________________ CONFERENCES AND SYMPOSIA 141st Assembly of the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU): The 141st Assembly of the IPU was held in Belgrade, Serbia from 13 to 17 October, 2019. An Indian Parliamentary Delegation led by Shri Om Birla, Hon’ble Speaker, Lok Sabha and consisting of Dr. Shashi Tharoor, Member of Parliament, Lok Sabha; Ms. Kanimozhi Karunanidhi, Member of Parliament, Lok Sabha; Smt. -

Parliamentary Bulletin

ParliamentaryRAJYA SABHA Bulletin PART-II Nos. 57714-57717] THURSDAY, APRIL 26, 2018 No. 57714 Bill Office Statement showing the BILLS PASSED by the Houses of Parliament during the Two Hundred and Forty Fifth Session (2018) of the Rajya Sabha and ASSENTED TO BY THE PRESIDENT S. N. Title of the Bill Date on, and Date on Date on Date of Act Date of Remarks House in which passed which passed/ President’s No. Publication in which by the returned by Assent the Gazette introduced originating the other House House 1. The Payment of 18/12/2017 15/03/2018 22/03/2018 28/03/2018 12 of 29/03/2018 Gratuity L .S. 2018 (Amendment) Bill, 2018. 2 . 2. The Finance Bill, 01/02/2018 14/03/2018 ------- 29/03/2018 13 of 29/03/2018 Money Bill 2018. L .S. 2018 . 3. The 14/03/2018 14/03/2018 ------- 29/03/2018 14 of 29/03/2018 Money Bill Appropriation L .S. 2018 (No.2) Bill, 2018. 4. The 14/03/2018 14/03/2018 ------- 29/03/2018 15 of 29/03/2018 Money Bill Appropriation L .S. 2018 (No.3) Bill, 2018. ____________ .The Bills could not be returned by the Rajya Sabha and were deemed to have been passed by both Houses under article 109(5) of the Constitution. 3 No. 57715 Bill Office Statements showing the BILLS PENDING in the Rajya Sabha at the end of Two Hundred and Forty Fifth Session (2018) Statement-I GOVERNMENT BILLS Sl. Title of the Bill Ministry/ Remarks No. Department 1. -

Government of India Ministry of Labour and Employment

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF LABOUR AND EMPLOYMENT LOK SABHA STARRED QUESTION NO. 23 TO BE ANSWERED ON 24.06.2019 EPF PENSION *23. SHRI N.K. PREMACHANDRAN: Will the Minister of LABOUR AND EMPLOYMENT be pleased to state: (a)whether the Government has received report from the Committee appointed for study of the issues of EPF pensioners and if so, the details thereof; (b)the details of the recommendations of the said Committee; (c)whether the Government has initiated action for implementation of the recommendations of the said Committee and if so, the details thereof; (d)whether the Government proposes to increase the minimum pension for EPF pensioners and if so, the details thereof; and (e)whether the Government also proposes to stop the realisation of amount from the pension on account of commutation of pension after realising the commuted amount and if so, the details thereof? ANSWER MINISTER OF STATE (IC) FOR LABOUR AND EMPLOYMENT (SHRI SANTOSH KUMAR GANGWAR) (a) to (e): A statement is laid on the Table of the House. * ****** STATEMENT REFERRED TO IN REPLY TO PARTS (a) TO (e) OF LOK SABHA STARRED QUESTION NO. 23 TO BE ANSWERED ON 24.06.2019 BY SHRI N.K. PREMACHANDRAN REGARDING EPF PENSION. (a) & (b): Yes, Sir. The Committee appointed for Evaluation and Review of the Employees’ Pension Scheme, 1995, headed by Additional Secretary, Ministry of Labour and Employment has submitted the report on 21st December, 2018. The report inter-alia has given observations/ recommendations on the following issues: i. Increase of Minimum Monthly Member Pension ii. -

Parliamentary Bulletin

RAJYA SABHA Parliamentary Bulletin PART-II Nos.: 51585-51586] FRIDAY, JANUARY 10, 2014 No. 51585 Table Office Retirement of Members of Rajya Sabha on the expiration of their Term of Office In pursuance of the provisions contained in article 83(1) of the Constitution, the following Members of Rajya Sabha will retire on the expiration of their term of office, in the year 2014: — DATE OF EXPIRATION OF TERM ANDHRA PRADESH - 6 1. Dr. T. Subbarami Reddy 2. Shri Nandi Yellaiah 3. Shri Mohd. Ali Khan 09-04-2014 4. Shrimati T. Ratna Bai 5. Dr. K.V. P. Ramachandra Rao 6. Vacant ARUNACHAL PRADESH - 1 1. Shri Mukut Mithi 26-05-2014 ASSAM - 3 1. Shri Bhubaneswar Kalita 2. Shri Birendra Prasad Baishya 09-04-2014 3. Shri Biswajit Daimary 2 BIHAR - 5 1. Dr. C.P. Thakur 2. Shri Shivanand Tiwari 3. Shri N.K. Singh 09-04-2014 4. Shri Prem Chand Gupta 5. Shri Sabir Ali CHHATTISGARH - 2 1. Shri Motilal Vora 09-04-2014 2. Shri Shivpratap Singh GUJARAT - 4 1. Prof. Alka Balram Kshatriya 2. Shri Natuji Halaji Thakor 09-04-2014 3. Shri Parshottam Khodabhai Rupala 4. Shri Bharatsinh Prabhatsinh Parmar HARYANA - 2 1. Shri Ishwar Singh 09-04-2014 2. Dr. Ram Prakash HIMACHAL PRADESH - 1 1. Shri Shanta Kumar 09-04-2014 JHARKHAND - 2 1. Shri Jai Prakash Narayan Singh 2. Shri Parimal Nathwani 09-04-2014 KARNATAKA - 4 1. Shri S.M. Krishna 2. Dr. Prabhakar Kore 25-06-2014 3. Shri M. Rama Jois 4. Shri B.K. Hariprasad 3 MADHYA PRADESH - 3 1. -

Government of India Ministry of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF MICRO, SMALL AND MEDIUM ENTERPRISES LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 982 TO BE ANSWERED ON 27.06.2019 JOBS CREATED BY KVIC 982. SHRI SUNIL DATTATRAY TATKARE: DR. HEENA GAVIT: SHRIMATI SUPRIYA SULE: DR. SUBHASH RAMRAO BHAMRE: DR. AMOL RAMSING KOLHE: Will the Minister of MICRO, SMALL AND MEDIUM ENTERPRISES be pleased to state: (a) the number of new jobs created by the Khadi and Village Industries Commission (KVIC) under the ambitious Prime Minister Employment Generation Programme (PMEGP) during each of the last three years and the current year; (b) whether KVIC has been given target for setting up new PMEGP projects and for creating more employment during 2018- 2019 and if so, the details thereof and the funds allocated and the steps taken by KVIC to achieve the target; (c) whether the margin money subsidy is being paid directly into the beneficiary account through Direct Benefit Transfer; (d) if so, the number of beneficiaries benefited during the last three years; and (e) whether digitalization of PMEGP by KVIC has helped in curtailing interference of middlemen and introduction of transparent system and if so, the details thereof and the other steps taken by the Government to promote Khadi products in the country and internationally so that more new jobs could be created? ANSWER MINISTER OF MICRO, SMALL AND MEDIUM ENTERPRISES (SHRI NITIN GADKARI) (a): The number of new job opportunities created by the Khadi and Village Industries Commission (KVIC) under the ambitious Prime Minister’s Employment Generation Programme (PMEGP) during the last three years and the current year, year-wise is as follows: Year Employment Generated 2016-17 407840 2017-18 387184 2018-19 587416 2019-20 29048 (As on 19.06.2019) (b): The target and achievement of new PMEGP projects during the financial year 2018-19 is placed at Annexure-I. -

Lok Sabha Debates

Uncorrected – Not for Publication LSS-D-I LOK SABHA DEBATES (Part I -- Proceedings with Questions and Answers) The House met at Eleven of the Clock. Thursday, December 11, 2014/ Agrahayana 20, 1936 (Saka) 11.12.2014 :: jr-kvj Uncorrected / Not for Publication 2 LOK SABHA DEBATES PART I – QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS Thursday, December 11, 2014/ Agrahayana 20, 1936 (Saka) CONTENTS PAGES OBITUARY REFERENCE 1 … 2-4 ORAL ANSWERS TO STARRED QUESTIONS 4A-24 (S.Q. NO. 261 TO 264 ) WRITTEN ANSWERS TO STARRED QUESTIONS 25-40 (S.Q. NO. 265 TO 280) WRITTEN ANSWERS TO UNSTARRED QUESTIONS 41-270 (U.S.Q. NO. 2991 TO 3220) For Proceedings other than Questions and Answers, please see Part II. 11.12.2014 :: jr-kvj Uncorrected / Not for Publication 3 Uncorrected – Not for Publication LSS-D-I LOK SABHA DEBATES (Part II - Proceedings other than Questions and Answers) Thursday, December, 11, 2014/ Agrahayana 20, 1936 (Saka) (Please see the Supplement also) 11.12.2014 :: jr-kvj Uncorrected / Not for Publication 4 LOK SABHA DEBATES PART II –PROCEEDINGS OTHER THAN QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS Thursday, December 11, 2014/ Agrahayana 20, 1936 (Saka) CONTENTS PAGES REFERENCE: CONGRATULATIONS TO 271 VISUALLY IMPAIRED INDIAN CRICKET TEAM ON WINNING THE WORLD CUP, 2014 IN CAPE TOWN, SOUTH AFRICA PAPERS LAID ON THE TABLE 272-92 MESSAGES FROM RAJYA SABHA 293 REPORT OF COMMITTEE ON ESTIMATES 294 1st Report REPORTS OF PUBLIC ACCOUNTS COMMITTEE 294 7th – 10 th Reports STANDING COMMITTEE ON SCIENCE & 295 TECHNOLOGY, ENVIRONMENT & FORESTS 253 rd Report SPECIAL MENTIONS 296-321 BILL INTRODUCED 322-25 Public Premises (Eviction of Unauthorised Occupants) Amendment Bill MATTERS UNDER RULE 377 –LAID 326-37 Shri Om Birla 326 Dr.