DLHS June 2021 Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notice of Uncontested Elections

NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION West Northamptonshire Council Election of Parish Councillors for Arthingworth on Thursday 6 May 2021 I, Anna Earnshaw, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Arthingworth. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) HANDY 5 Sunnybank, Kelmarsh Road, Susan Jill Arthingworth, LE16 8JX HARRIS 8 Kelmarsh Road, Arthingworth, John Market Harborough, Leics, LE16 8JZ KENNEDY Middle Cottage, Oxendon Road, Bernadette Arthingworth, LE16 8LA KENNEDY (address in West Michael Peter Northamptonshire) MORSE Lodge Farm, Desborough Rd, Kate Louise Braybrooke, Market Harborough, Leicestershire, LE16 8LF SANDERSON 2 Hall Close, Arthingworth, Market Lesley Ann Harborough, Leics, LE16 8JS Dated Thursday 8 April 2021 Anna Earnshaw Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Civic Offices, Lodge Road, Daventry, Northants, NN11 4FP NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION West Northamptonshire Council Election of Parish Councillors for Badby on Thursday 6 May 2021 I, Anna Earnshaw, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Badby. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) BERRY (address in West Sue Northamptonshire) CHANDLER (address in West Steve Northamptonshire) COLLINS (address in West Peter Frederick Northamptonshire) GRIFFITHS (address in West Katie Jane Northamptonshire) HIND Rosewood Cottage, Church -

Animal and Sporting Paintings in the Penkhus Collection: the Very English Ambience of It All

Animal and Sporting Paintings in the Penkhus Collection: The Very English Ambience of It All September 12 through November 6, 2016 Hillstrom Museum of Art SEE PAGE 14 Animal and Sporting Paintings in the Penkhus Collection: The Very English Ambience of It All September 12 through November 6, 2016 Opening Reception Monday, September 12, 2016, 7–9 p.m. Nobel Conference Reception Tuesday, September 27, 2016, 6–8 p.m. This exhibition is dedicated to the memory of Katie Penkhus, who was an art history major at Gustavus Adolphus College, was an accomplished rider and a lover of horses who served as co-president of the Minnesota Youth Quarter Horse Association, and was a dedicated Anglophile. Hillstrom Museum of Art HILLSTROM MUSEUM OF ART 3 DIRECTOR’S NOTES he Hillstrom Museum of Art welcomes this opportunity to present fine artworks from the remarkable and impressive collection of Dr. Stephen and Mrs. Martha (Steve and Marty) T Penkhus. Animal and Sporting Paintings in the Penkhus Collection: The Very English Ambience of It All includes sixty-one works that provide detailed glimpses into the English countryside, its occupants, and their activities, from around 1800 to the present. Thirty-six different artists, mostly British, are represented, among them key sporting and animal artists such as John Frederick Herring, Sr. (1795–1865) and Harry Hall (1814–1882), and Royal Academicians James Ward (1769–1859) and Sir Alfred Munnings (1878–1959), the latter who served as President of the Royal Academy. Works in the exhibit feature images of racing, pets, hunting, and prized livestock including cattle and, especially, horses. -

Everdon Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Plan

Everdon Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Plan Consultation Draft May 2019 0 Contents 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Why has this document been produced? ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 1.2 What status will this document have? ................................................................................................................................................................. 4 1.3 What is the purpose of this document? ............................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.4 How is this document structured?........................................................................................................................................................................ 5 1.5 Who is this document intended for? .................................................................................................................................................................... 5 1.6 How do I comment on this document? ................................................................................................................................................................ 6 2 Policy and -

Daventry District Council Weekly List of Applications Registered 30/04/2018

DAVENTRY DISTRICT COUNCIL WEEKLY LIST OF APPLICATIONS REGISTERED 30/04/2018 App No. DA/2018/0015 Registered Date 17/04/2018 Location The Plough, Newnham Road, Everdon, Northamptonshire Proposal Variation of Conditions 6 and 7 of planning permission DA/2016/1045 (Conversion of ground and first floors of barn to holiday let, extensions and alterations to existing stables) to allow for a longer term let as a sole or main place of residence Parish Everdon Case Officer Angela Brockett Easting: 459504 Northing: 257461 UPRN 28031487 App No. DA/2018/0203 Registered Date 18/04/2018 Location Land At Foxhill Stables, Foxhill Road, West Haddon, Northamptonshire NN6 7BG Proposal Construction of stable block Parish West Haddon Case Officer Sue Barnes Easting: 462883.9 Northing: 270375.4 UPRN 28058977 App No. DA/2018/0234 Registered Date 16/04/2018 Location The Laurels 8, Kings Lane, Yelvertoft, Northamptonshire, NN6 6LX Proposal Demolition of existing extension. Construction of two storey extension. Parish Yelvertoft Case Officer Angela Brockett Easting: 459595 Northing: 275473 UPRN 28015671 App No. DA/2018/0253 Registered Date 13/04/2018 Location Village Farm 15, Rugby Road, Barby, Northamptonshire, CV23 8UA Proposal Construction of domestic storage building Parish Barby Case Officer Mr S Cadman Easting: 454153 Northing: 270477 UPRN 28013899 App No. DA/2018/0276 Registered Date 19/04/2018 Location Staverton Hill Farm, Badby Lane, Staverton, Northamptonshire, NN11 6DE Proposal Construction of new office building in lieu of building to be converted to offices under planning approval DA/2009/0550 which is to be demolished Parish Staverton Case Officer Mr E McDowell Easting: 454679 Northing: 261103 UPRN 28032730 App No. -

Snorscomb Mill Everdon • Nr Daventry • Northamptonshire

SNORSCOMB MILL EvErdon • nr davEntry • northamptonshirE SNORSCOMB MILL EvErdon • nr davEntry • northamptonshirE Distances approximate: Daventry 6.3 miles • Towcester 10.5 miles Northampton 12.5 miles (London/Euston via rail from 1 hour) Milton Keynes 23 miles (London/Euston via rail from 35 minutes) M1 motorway (junction 16) 6.9 miles • M40 motorway (junction 11) 16.2 miles. A substantial 19th century former mill house, extensively rebuilt in the 1960’s, occupying an enviable position surrounded by open fields. Entrance hall and inner hall with cloakroom • Drawing room • Dining room • Kitchen/breakfast room Utility room • Playroom/office • First floor study Master bedroom with en-suite shower room & dressing room Three further bedrooms (one with en-suite shower room) • Family bathroom Guest wing with Sitting room, Bedroom & Shower room Garaging & Store Extensive landscaped gardens with mill race & stream frontage In all approximately 1.5 acres Savills 36 South Bar Banbury Oxfordshire OX16 9AE Tel: 01295 228000 [email protected] savills.co.uk Situation Everdon is a popular rural village in mid Northamptonshire amidst unspoilt rolling countryside. Daventry and Towcester are the local towns with the usual shopping and leisure facilities. Northampton, Banbury, Rugby and Milton Keynes are regional centres and provide train services to London and the North. The motorway network can be joined via junction 16 of the M1 motorway and junction 11 of the M4 motorway. State primary schools can be found at Newnham, Badby and Weedon with secondary schools in Daventry and Towcester. There is a wide range of private schools in the locality including Maidford School, Bilton Grange at Dunchurch, Winchester House School at Brackley, Spratton, Maidwell, Rugby, Stowe, Bloxham, Tudor Hall at Banbury, Pitsford, Oundle, Northampton High School for Girls, Uppingham, Oakham and Kimbolton. -

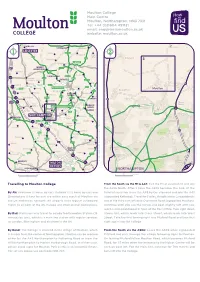

AA How to Find Us 2017

Moulton College Main Centre Moulton, Northampton, NN3 7RR Tel: +44 (0)1604 491131 email: [email protected] website: moulton.ac.uk WIGSTON A47 N UPPINGHAM Duddington N Holcot W E LEICESTER W E Hallaton A6003 2 1 Harringworth King’s S A6 Cliffe S A43 Pitsford Medbourne 3 A 5 CORBY 1 Cottingham 9 9 A427 M1 MARKET A427 HARBOROUGH Gilmorton A43 A6 A508 A4304 Brigstock DESBOROUGH A6003 20 Husbands A508 A43 Bosworth Clipston ROTHWELL A6116 Islip Welford Swinford A14 19 Cranford A14 A14 Naseby KETTERING Moulton Boughton Broughton A45 M1 Yelvertoft Thornby BURTON Ringstead Lamport LATIMER A A43 5 Finedon 18 West Haddon 1 A508 A509 Boughton 9 RAUNDS 9 Brixworth A6 Green A428 Harrowden M45 17 Round East Spinney Haddon HIGHAM 2 WELLINGBOROUGH FERRERS A5 Long Moulton Mears Ashby Moulton Park A5076 Buckby RUSHDEN A45 00 A5076 A45 NORTHAMPTON Earls Wollaston A6 DAVENTRY Barton A45 A509 16 A45 Sharnbrook Boothville A428 Yardley Bozeat 15a Hastings Spinney A50 Hill Everdon Bugbrooke 15 Lavendon A5123 A43 Kingsthorpe The Arbours A43 Roade A428 Blakesley Olney Licence Number PU100029016 Licence Number PU100029016 . A508 Stagsden Towcester M1 A5095 Culworth A509 A422 Hanslope KEMPSTON Queen’s All rights reserved All rights reserved A5 NEWPORT Kingsley . Silverstone Wootton A508 Park A PAGNELL Park 413 Cosgrove A43 Cranfield A421 Greatworth 14 Kingsthorpe A5095 Hollow A43 © Crown Copyright 422 © Crown Copyright Weston BRACKLEY A Abington 13 Favell A45 A422 MILTON A KEYNES 421 BUCKINGHAM A5 A421 Woburn NORTHAMPTON 0 5 10 KM 0 500 1000 METRES Travelling to Moulton College From the South via the M1 & A43: Exit the M1 at Junction 15 and join the A508 North. -

Jon, 91 Year Old Harry Leslie Smith Gave One of the Most Moving Speeches I've Ever Heard at Conference Last Week. His Story Abou

From: Andy Burnham [email protected] Subject: Heartbreaking Date: 29 September 2014 17:22 To: Jon Lansman Jon, 91 year old Harry Leslie Smith gave one of the most moving speeches I've ever heard at conference last week. His story about his sister is just heartbreaking. This is something everyone should hear. You can read his words below or watch his full speech here: http://action.labour.org.uk/Harrys-story "I came into this world in the rough and ready year of 1923. I am from Barnsley and I can tell you that my childhood, like so many others from that era, was not an episode from Downton Abbey. Instead, it was a barbarous time. It was a bleak time. It was an uncivilized time because public healthcare didn't exist. Back then hospitals, doctors and medicine were for the privileged few because they were run for profit rather than as a vital state service that keeps a nation's citizens fit and healthy. My memories stretch back almost a hundred years, and if I close my eyes, I can smell the poverty that oozed from the dusky tenement streets of my boyhood. I can taste on my lips the bread and drippings I was served for my tea. I can remember extreme hunger, and my parent's undying love for me. I can still feel my mum and dad's desperation as they tried to keep our family safe and healthy in the slum we called home. Poor mum and dad. No matter how hard they tried to protect me and my sisters, the cards were stacked against them because common diseases trolled our neighbourhoods and snuffed out life like a cold breath on a warm candle flame. -

Statement of Accounts 2018/2019

Contents Page Leicestershire County Council Statement of Accounts 4 Narrative Statement Movement in Reserves Statement (MIRS) 11 Comprehensive Income and Expenditure Statement (CIES) 12 Balance Sheet 13 Cash Flow Statement 14 Notes to the Primary Statements 15-83 Statement of Responsibilities for the Statement of Accounts 84 Leicestershire County Council Pension Fund Accounts 85 Fund Account 87 Net Assets Statements 87 Notes to the Accounts 88 Pension Fund Actuarial Statement 2018/19 110 Pension Fund Accounts Reporting Requirement 112 Statement of Responsibilities for Leicestershire County Council Pension Fund 114 Audit Opinion 115 Annual Governance Statement 121 Glossary of Terms 136 Copies of the Statement of Accounts and Annual Governance Statement are available from the Technical Accounting Team, Corporate Resources Department, Leicestershire County Council, County Hall, Glenfield, Leicester, LE3 8RB. Alternatively, the accounts can be viewed on the County Council’s website by visiting: http://www.leicestershire.gov.uk/ Primary Statements Introduction to the Statement of Accounts Councillor Preface Being the lowest funded County Council in the Country has brought many challenges but one which we have met with real determination. The County Council continues to face significant financial, demographic and service demand challenges. It needs to deliver savings of £75m (of which £20m remain unidentified) over the next four financial years to 2022/23, with £13m savings to be made in 2019/20. This is a challenging task especially given that savings of £200m have already been delivered over the last nine years. In addition, over the period of the Medium Term Financial Strategy, growth of £50m is required to meet demand and cost pressures with £14m required in 2019/20. -

By Jean-Nicolas Beuze, UNHCR Canada Representative

FALL 2018 ISSUE Harry’s last stand Meet the 95-year-old activist rallying for refugees | PAGE 4 Heartbreak Country in crisis Why are Venezuelans and healing compelled to leave? | PAGE 16 Canadian connection The road ahead for the Long-lost relatives reunite resilient Rohingya | PAGE 8 12,000 kilometres from home | PAGE 20 CONTENTS CONTRIBUTORS EDITOR 3 Letter from the Representative Lauren La Rose 4 Harry’s last stand: Meet the 95-year-old activist rallying for refugees ASSISTANT EDITOR Margaret Cruickshanks 6 Cold comfort: Helping refugee families during the winter months WRITERS 8 The Rohingya crisis: A year of heartbreak, hope and healing Jean-Nicolas Beuze Erla Cabrera 12 A Canadian UNHCR aid worker on the front lines in Bangladesh Fiona Irvine-Goulet Lauren La Rose Opinion: There is a refugee crisis—but not in Canada 14 DESIGN Ripple Creatives Inc. 16 Venezuela: Snapshot of a country in crisis Front and back cover photos: 18 UNHCR Canada staffers supporting Venezuelans in crisis © UNHCR/Andrew McConnell Front cover: Morsheda, 12, and her 20 Lost and found: A family reunion for Somali refugees in Canada niece, Nisma, 10 months, take an early morning walk to warm up from the cold inside their shelter at Kutupalong LGBTI refugee shares story of survival 22 Camp in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. UNHCR is working tirelessly with its 23 Canadian community hub for newcomers helps Syrians in crisis partners to provide assistance to Rohingya refugees. 24 A 1,600-kilometre bike ride propels entrepreneur into action 26 Her turn: A pathway to education for refugee girls in Kenya 27 Paying it forward: 3 gifts that give back Send us your feedback We would love to hear from you. -

Further Information on These Decisions Can Be Obtained from The

Delegated Weekly List For period Monday 9 September 2013 and Friday 13 September 2013 Further information on these decisions can be obtained from the Daventry District Council Website at: http://www.daventrydc.gov.uk/living/planning-and-building-control/search-comment-planning/ Application No. Location Proposal Decision Decision Date DA/2013/0469 3, Stubbs Road, Everdon, Alterations to existing side structure to Approval 12-Sep-2013 Northamptonshire, NN11 3BN form single storey lean-to timber side Householder extension (part retrospective) App DA/2013/0507 Tithe Farm House, Moulton Road, Construction of outdoor equestrian Approval Full 11-Sep-2013 Holcot, Northamptonshire, NN6 schooling arena and change of use from 9SH existing paddock to equestrian schooling arena. Formation of a bund (part retrospective). DA/2013/0520 Manor Farm, Bakers Lane, Single storey side extension, new timber Approval 12-Sep-2013 Norton, Northamptonshire, NN11 windows and doors and new double Householder 2EL garage with storage within roofspace and App single storey link between garage and extension DA/2013/0532 36, Churchill Road, Welton, Certificate Of Lawfulness (Proposed) for Refusal Cert of 11-Sep-2013 Northamptonshire, NN11 2JH a single storey rear extension Lawfulness Prop DA/2013/0535 63/65, Broadlands, Brixworth, Work to trees subject of Tree Preservation Approval TPO 12-Sep-2013 Northamptonshire, NN6 9BH Order DA 121 DA/2013/0538 Dale Farm, Harborough Road, Conversion of stone barn to holiday let Approval Full 11-Sep-2013 Maidwell, Northamptonshire, NN6 accommodation 9JE DA/2013/0541 Windmill Barns 5, Windmill Listed Building Consent for removal and Approval Listed 11-Sep-2013 Gardens, Staverton, replacement of windows/doors Building Delegated Weekly List For period Monday 9 September 2013 and Friday 13 September 2013 Further information on these decisions can be obtained from the Daventry District Council Website at: http://www.daventrydc.gov.uk/living/planning-and-building-control/search-comment-planning/ Application No. -

Ebook Download Harrys Last Stand: How the World My Generation

HARRYS LAST STAND: HOW THE WORLD MY GENERATION BUILT IS FALLING DOWN, AND WHAT WE CAN DO TO SAVE IT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Harry Leslie Smith | 224 pages | 10 Feb 2015 | Icon Books Ltd | 9781848317369 | English | Duxford, United Kingdom Harry's Last Stand Brand new: Lowest price The lowest-priced brand-new, unused, unopened, undamaged item in its original packaging where packaging is applicable. Binding: Paperback Language: english. Will be clean, not soiled or stained. See all 3 brand new listings. Buy It Now. Add to cart. About this product Product Information In November , year-old Yorkshireman, RAF veteran and ex-carpet salesman Harry Leslie Smith's Guardian article - 'This year, I will wear a poppy for the last time' - was shared almost 60, times on Facebook and started a huge debate about the state of society. Now he brings his unique perspective to bear on NHS cutbacks, benefits policy, political corruption, food poverty, the cost of education - and much more. From the deprivation of s Barnsley and the terror of war to the creation of our welfare state, Harry has experienced how a great civilisation can rise from the rubble. But at the end of his life, he fears how easily it is being eroded. Harry's Last Stand is a lyrical, searing modern invective that shows what the past can teach us, and how the future is ours for the taking. If it doesn't make you angry there's something wrong with you. It's inspirational stuff. Labour should read to get fire in bellies. Tories should read in shame. -

9–19 June 2016

9–19 June 2016 belfastbookfestival.com “The Belfast Book Festival opens up the incredible worlds of litera- ture and the imagination by allowing the best international and local writers to present their work to audiences in the most intimate and congenial of settings. The Arts Council’s support as principal funder reflects our confidence in this festival to extend the appeal of all literary genres so that everyone, from the most tentative to the most seasoned of readers, has the opportunity to experience the full and inimitable pleasure of books.” Damian Smyth, Head of Literature and Drama, Arts Council of Northern Ireland “Welcome to the Belfast Book Festival 2016 run by the Crescent Arts Centre. Now firmly established and recognised on the UK, Irish and international literary circuit, we have another incredible programme for all ages, tastes and genres. We are grateful to our funders, the Arts Council of Northern Ireland 9-19 June 2016 and Belfast City Council and to our Events Sponsor Standard Utilities, and other key sponsors the Europa Hotel and Nicholson Bass. Togeth- er by creating a shared experience we all contribute to something magical across the city. Books matter and authors matter. They must be cherished. This is our ethos and vision in our programming for this year’s Belfast Book Festival.” Contents Deepa Mann-Kler, Chair, Crescent Arts Centre Thursday 9th June 5 Friday 10th June 9 Saturday 11th June 13 Sunday 12th June 19 Booking Information Monday 13th June 25 Tues 14th June 29 Wednesday 15th June 39 Online Thursday 16th June 45 Fri 17th June 50 www.belfastbookfestival.com Sat 18th June 55 Sunday 19th June 61 By Telephone 028 9024 2338 Festival pull out 35 Workshops, Community Outreach, & Weeklong events 66 In Person More Information 69 The Crescent Arts Centre Family Fun Day 70 2 – 4 University Road Belfast, BT7 1NH Thursday 9th June PROUD TO BE SUPPORTING THE BELFAST BOOK FESTIVAL Alan Glynn Three Voices Carcanet’s New David Park Generation Showcase Paradime Eleanor Hooker, Trevor Gods And Angels With Robert J.E.