The Impact of Civil Action on Levels of Violence: Comparing Communities During Northern Ireland’S Troubles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roinn Cosanta. Bureau of Military History, 1913-21

ROINN COSANTA. BUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21 STATEMENT BY WITNESS 145 DOCUMENT NO. W.S. Witness Sean Corr Identity Member Of I.R.B., I.V. and I.R.A. 1915-1921. Subject National activities, Carrickmore District Co. Tyrone from 1906 Conditions, if any, stipulated by Witness Nil File No. S.987 Form B.S.M.2. STATEMENT BY SEAN CORR Late of Carrickmore. Co. Tyrone. Now living in Cabra, Dublin. Sinn Fein was organised in Carrickmore Parish, County Tyrone, in 1906. The organisation was then known as the Dungannon Club. There was at this time an I.R.B. Centre in Carrickmore composed of the following members:- Dr. Patrick McCartan, Michael McCartan, Christy Meenagh, Peter Fox, James McElduff, Patrick Marshal, James Conway, Tom McNally, Patrick McNally, Patrick Quinn and Bernard McCartan. Bulmer Hobson addressed a meeting of the Dungannon Club in 1906 or 1907. The Chairman of the Club, who presided at the meeting, was a local Justice of the Peace who id not know that. the men behind the Club and the men who were responsible for getting Bulmer Hobson to address the Club meeting were the I.R.B. Organisation. The Chairman-was particularly keen on the objects of the Dungannon Clubs, but' would not in any way allow hims elf to be consciously associated with the I.R.B. The Dungannon Club. remained in existence up to the starting of the National Volunteers in the area. At the start of the Volunteers in this area the organisation was known as the National Volunteers, and no question arose of a division in the Volunteer organisation until the split in September 1914. -

Killyclogher, Omagh. Co. Tyrone

Important Information about Zest: Killyclogher, Omagh. Co. Tyrone First of all, we would like to take this opportunity to thank all the generous people of the area who have made it possible for us to deliver our services in the Killyclogher office. Your kindness and generosity are an example to all communities in taking responsibility for addressing the problems of self-harm and suicide. We are extremely grateful for this opportunity. We, at Zest, believe it is important to point out that our office in Killyclogher is a therapy centre and not a drop-in centre. There are 2 reasons for this: 1. Firstly, and the most important reason, is confidentiality. It is essential that all our clients feel safe and that their meetings with us for counselling remain private. This would be very difficult to guarantee if the office was open to the general public on a drop-in basis. 2. Secondly, due to the size of the unit, we are only able to accommodate a small number of people at any given time. However, we can overcome these difficulties. If anyone who wishes to make enquiries for information or who would like to be seen for support, you can telephone the Derry office on 028 71 266999 an appointment will be given to be seen in Killyclogher. You may also call into the Killyclogher office on Friday mornings between 10.30am and 1.30pm to talk to a staff member. We can also arrange to meet small groups at any time, outside of the therapy times. We currently have 4 counsellors seeing clients in Killyclogher, 2 counsellors on Wednesdays and 2 on Thursdays (from 9.00am – 4.00pm each day). -

05 November 2019

05 November 2019 Dear Councillor You are invited to attend a meeting of the Planning Committee to be held in The Chamber, Magherafelt at Mid Ulster District Council, Ballyronan Road, MAGHERAFELT, BT45 6EN on Tuesday, 05 November 2019 at 19:00 to transact the business noted below. Yours faithfully Anthony Tohill Chief Executive AGENDA OPEN BUSINESS 1. Apologies 2. Declarations of Interest 3. Chair's Business Matters for Decision Development Management Decisions 4. Receive Planning Applications 5 - 140 Planning Reference Proposal Recommendation 4.1. LA09/2018/0462/F Agricultural shed 95m W of 65 APPROVE Drumgrannon Road, Moy, for Seamus Conroy. 4.2. LA09/2018/1537/F Alterations & extension to existing APPROVE dwelling to include an increase in ridge height at 18 Tamlaghduff Road, Bellaghy, for Dympna McPeake. 4.3. LA09/2018/1648/F Retention of open-sided storage APPROVE building at Blackrock Road, Toomebridge, for Creagh Concrete Products Ltd. 4.4. LA09/2019/0252/O Farm dwelling and garage 200m REFUSE Page 1 of 276 NE of 51 Gulladuff Road, Magherafelt, for James McPeake. 4.5. LA09/2019/0468/F 2 storey side annex extension to APPROVE provide granny flat; provision of 2 dormer windows and new retaining wall to rear garden at 40 Coolshinney Road, Magherafelt, for Claire McWilliams. 4.6. LA09/2019/0710/O Off site replacement dwelling and REFUSE domestic garage/store 70m SW of 11 Motalee Road, Magherafelt, for Mrs Gillian Montgomery. 4.7. LA09/2019/0750/F 6 dwellings within existing REFUSE Millbrook Housing Development at site 10m E of 1 Millbrook Close, Washingbay Road, Coalisland, for N & R Devine. -

Newspaper Licensing Agency - NLA

Newspaper Licensing Agency - NLA Publisher/RRO Title Title code Ad Sales Newquay Voice NV Ad Sales St Austell Voice SAV Ad Sales www.newquayvoice.co.uk WEBNV Ad Sales www.staustellvoice.co.uk WEBSAV Advanced Media Solutions WWW.OILPRICE.COM WEBADMSOILP AJ Bell Media Limited www.sharesmagazine.co.uk WEBAJBSHAR Alliance News Alliance News Corporate ALLNANC Alpha Newspapers Antrim Guardian AG Alpha Newspapers Ballycastle Chronicle BCH Alpha Newspapers Ballymoney Chronicle BLCH Alpha Newspapers Ballymena Guardian BLGU Alpha Newspapers Coleraine Chronicle CCH Alpha Newspapers Coleraine Northern Constitution CNC Alpha Newspapers Countydown Outlook CO Alpha Newspapers Limavady Chronicle LIC Alpha Newspapers Limavady Northern Constitution LNC Alpha Newspapers Magherafelt Northern Constitution MNC Alpha Newspapers Newry Democrat ND Alpha Newspapers Strabane Weekly News SWN Alpha Newspapers Tyrone Constitution TYC Alpha Newspapers Tyrone Courier TYCO Alpha Newspapers Ulster Gazette ULG Alpha Newspapers www.antrimguardian.co.uk WEBAG Alpha Newspapers ballycastle.thechronicle.uk.com WEBBCH Alpha Newspapers ballymoney.thechronicle.uk.com WEBBLCH Alpha Newspapers www.ballymenaguardian.co.uk WEBBLGU Alpha Newspapers coleraine.thechronicle.uk.com WEBCCHR Alpha Newspapers coleraine.northernconstitution.co.uk WEBCNC Alpha Newspapers limavady.thechronicle.uk.com WEBLIC Alpha Newspapers limavady.northernconstitution.co.uk WEBLNC Alpha Newspapers www.newrydemocrat.com WEBND Alpha Newspapers www.outlooknews.co.uk WEBON Alpha Newspapers www.strabaneweekly.co.uk -

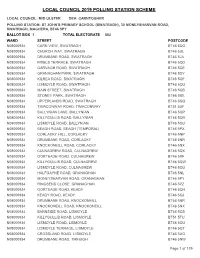

Local Council 2019 Polling Station Scheme

LOCAL COUNCIL 2019 POLLING STATION SCHEME LOCAL COUNCIL: MID ULSTER DEA: CARNTOGHER POLLING STATION: ST JOHN'S PRIMARY SCHOOL (SWATRAGH), 30 MONEYSHARVAN ROAD, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA, BT46 5PY BALLOT BOX 1 TOTAL ELECTORATE 882 WARD STREET POSTCODE N08000934CARN VIEW, SWATRAGH BT46 5QG N08000934CHURCH WAY, SWATRAGH BT46 5UL N08000934DRUMBANE ROAD, SWATRAGH BT46 5JA N08000934FRIELS TERRACE, SWATRAGH BT46 5QD N08000934GARVAGH ROAD, SWATRAGH BT46 5QE N08000934GRANAGHAN PARK, SWATRAGH BT46 5DY N08000934KILREA ROAD, SWATRAGH BT46 5QF N08000934LISMOYLE ROAD, SWATRAGH BT46 5QU N08000934MAIN STREET, SWATRAGH BT46 5QB N08000934STONEY PARK, SWATRAGH BT46 5BE N08000934UPPERLANDS ROAD, SWATRAGH BT46 5QQ N08000934TIMACONWAY ROAD, TIMACONWAY BT51 5UF N08000934BALLYNIAN LANE, BALLYNIAN BT46 5QP N08000934KILLYGULLIB ROAD, BALLYNIAN BT46 5QR N08000934LISMOYLE ROAD, BALLYNIAN BT46 5QU N08000934BEAGH ROAD, BEAGH (TEMPORAL) BT46 5PX N08000934CORLACKY HILL, CORLACKY BT46 5NP N08000934DRUMBANE ROAD, CORLACKY BT46 5NR N08000934KNOCKONEILL ROAD, CORLACKY BT46 5NX N08000934CULNAGREW ROAD, CULNAGREW BT46 5QX N08000934GORTEADE ROAD, CULNAGREW BT46 5RF N08000934KILLYGULLIB ROAD, CULNAGREW BT46 5QW N08000934LISMOYLE ROAD, CULNAGREW BT46 5QU N08000934HALFGAYNE ROAD, GRANAGHAN BT46 5NL N08000934MONEYSHARVAN ROAD, GRANAGHAN BT46 5PY N08000934RINGSEND CLOSE, GRANAGHAN BT46 5PZ N08000934GORTEADE ROAD, KEADY BT46 5QH N08000934KEADY ROAD, KEADY BT46 5QJ N08000934DRUMBANE ROAD, KNOCKONEILL BT46 5NR N08000934KNOCKONEILL ROAD, KNOCKONEILL BT46 5NX N08000934BARNSIDE ROAD, LISMOYLE -

Report on Neighbourhood Renewal Programme Reporting Officer Claire

Report on Neighbourhood Renewal Programme Reporting Officer Claire Linney Contact Officer Oliver Donnelly Is this report restricted for confidential business ? Yes If ‘Yes’, confirm below the exempt information category relied upon No x 1.0 Purpose of Report 1.1 To update members on the Neighbourhood Renewal Programme with detail on each project delivered across the two Neighbourhood Renewal Areas 2.0 Background 2.1 The Neighbourhood Renewal Programme aims to reduce the social and economic inequalities which characterise the most deprived areas across the region. It does so by making a long term commitment to communities to work in partnership to identify and prioritise needs, and co-ordinate interventions designed to address the underlying causes of poverty. Neighbourhood Renewal Partnerships were established in 2005 representative of local community interests together with appropriate Government Departments, public sector agencies, private sector interest and local elected representatives. 2.2 The estimated population for both areas based on NISRA’s population estimates (2015) show that Coalisland NRA was 2,744 and Dungannon was 1,782. 2.3 Multiple Deprivation Measure statistics (2010) based at Super Output Area level show Coalisland South ranked 82, Ballysaggart 169 and Coalisland North 175 out of a total of 890 Super Output Areas across Northern Ireland. Rank of Multiple Deprivation Measure Score (where 1 is most SOA NAME LGD NAME deprived) Coalisland South Dungannon 82 Ballysaggart Dungannon 169 Coalisland North Dungannon 175 There are 7 domains within the Multiple Deprivation Measure. The below table outlines the rank of the 3 Super Output Areas within each of the domains. -

The Belfast Gazette

NUMBER 2552 193 The Belfast Gazette Registered as a Newspaper State Intelligence FRIDAY, 30TH MAY, 1969 MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE (Scheme 2) that part of Clintycracken River flowing through or between the townlands of DRAINAGE SCHEME Clintycracken, Lenadremnagh, Gortna- gwyg, Drumhubbert, Back Upper, Scheme 1: Drumgallan Burn Magheralamfield, in the County of Tyrone; The Ministry of Agriculture for Northern Ireland hereby gives notice in pursuance of Section 5(l)(b) of (Scheme 3): that part of Ballygittle River flowing the Drainage Act (Northern Ireland) 1947 as extended through or between the townlands of by Section 6(2) of the Drainage Act (Northern Ire- Lenadremnagh, Gortnaglogh, Ballygittle, land) 1964, that a Scheme has been prepared for the Drumkern, Drumard, Gortnagwyn in better drainage of that part of Drumgallan Burn the County of Tyrone; flowing through or between the townlands of'Kil- which the Drainage Council have determined to be more Robinson, Kilmore Irvine, Drumgallan in the minor watercourses within the meaning of Section County of Tyrone, which the Drainage Council have 2(1) of the Drainage Act (Northern Ireland) 1964. determined to be a minor watercourse within the Copies of the Schemes may be inspected free of meaning of Section 2(1) of the Drainage Act (Nor- charge by any person during the period 2nd June, thern Ireland) 1964. 1969, to 2nd July, 1969, inclusive, at the offices of A copy of the Scheme may be inspected free of Tyrone County Council, County Hall, Omagh, also charge by any person during the period 2nd June, Dungannon Rural District Council, Market Square, 1969, to 2nd July, 1969, inclusive, at the offices of Dungannon, between the hours of 9.30 a.m. -

The RUC Handling of Certain Intelligence and Its Relationship with Government Communications Headquarters in Relation to the Omagh Bomb on 15 August 1998

Investigation Report The RUC handling of certain intelligence and its relationship with Government Communications Headquarters in relation to the Omagh Bomb on 15 August 1998 Public Statement by the Police Ombudsman for Northern Ireland arising from a referral by the Chief Constable, in accordance with Section 62 of the Police (Northern Ireland) Act 1998 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 On 4 May 2010, I received a Referral from the Chief Constable of the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) concerning a number of specific matters relating to the manner in which the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) Special Branch handled both intelligence and its relationship with Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) in relation to the Omagh Bombing on 15 August 1998. The referral originated from issues identified by the House of Commons Northern Ireland Affairs Committee. 1.2 In 2013 the Chief Constable made a further Referral to my Office in connection with the findings of a report commissioned by the Omagh Support and Self Help Group (OSSHG) in support of a full Public Inquiry into the Omagh Bombing. The report identified and discussed a wide range of issues, including a reported tripartite intelligence led operation based in the Republic of Ireland involving American, British and Irish Agencies, central to which was a named agent. It suggested that intelligence from this operation was not shared prior to, or with those who subsequently investigated the Omagh Bombing. 1 1.3 On 12 September 2013 the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, Theresa Villiers M.P. issued a statement explaining that there were not sufficient grounds to justify a further inquiry beyond those that had already taken place. -

A Seed Is Sown 1884-1900 (1) Before the GAA from the Earliest Times, The

A Seed is Sown 1884-1900 (1) Before the GAA From the earliest times, the people of Ireland, as of other countries throughout the known world, played ball games'. Games played with a ball and stick can be traced back to pre-Christian times in Greece, Egypt and other countries. In Irish legend, there is a reference to a hurling game as early as the second century B.C., while the Brehon laws of the preChristian era contained a number of provisions relating to hurling. In the Tales of the Red Branch, which cover the period around the time of the birth of Christ, one of the best-known stories is that of the young Setanta, who on his way from his home in Cooley in County Louth to the palace of his uncle, King Conor Mac Nessa, at Eamhain Macha in Armagh, practised with a bronze hurley and a silver ball. On arrival at the palace, he joined the one hundred and fifty boys of noble blood who were being trained there and outhurled them all single-handed. He got his name, Cuchulainn, when he killed the great hound of Culann, which guarded the palace, by driving his hurling ball through the hound's open mouth. From the time of Cuchulainn right up to the end of the eighteenth century hurling flourished throughout the country in spite of attempts made through the Statutes of Kilkenny (1367), the Statute of Galway (1527) and the Sunday Observance Act (1695) to suppress it. Particularly in Munster and some counties of Leinster, it remained strong in the first half of the nineteenth century. -

Brave Record Issue 6

Issue 6 Page !1 Brave Record Dungannon and Moy’s rich and varied naval service - Submariner WW1 - Polar expertise aided Arctic convoys - Leading naval surgeon - Naval compass inventor - Key role at Bletchley Park Northern Ireland - Service in the Royal Navy - In Remembrance Issue 6 Page !2 Moy man may be Northern Ireland’s first submariner loss HM Submarine D5 was lost on 03/11/1914. In the ship was 29 year old Fred Bradley. He had previously served during the Boer War. He had also served in HMS Hyacinth in the Somali Expedition. HMS D5 was a British D class submarine built by Vickers, Barrow. D5 was laid down on 23/2/1910, launched 28/08/1911 and was commissioned 19/02/1911. One source states she was sunk by a German mine laid by SMS Stralsund after responding to a German attack on Yarmouth by cruisers. The bombardment, which was very heavy and aimed at the civilian population, was rather ineffective, due to the misty weather and only a few shells landed on the beaches at Gorleston. In response, the submarines D3, E10 and D5 - the latter being under the command of Lt.Cdr. Godfrey Herbert, were ordered out into the roadstead to intercept the enemy fleet. Northern Ireland - Service in the Royal Navy - In Remembrance Issue 6 Page !3 Another source states HMS D5 was sunk by a British mine two miles south of South Cross Buoy off Great Yarmouth in the North Sea. 20 officers and men were lost. There were only 5 survivors including her Commanding Officer. -

Smythe-Wood Series A

Smythe-Wood Newspaper Index – “A” series – mainly Co Tyrone Irish Genealogical Research Society Dr P Smythe-Wood’s Irish Newspaper Index Selected families, mainly from Co Tyrone ‘Series A’ The late Dr Patrick Smythe-Wood presented a large collection of card indexes to the IGRS Library, reflecting his various interests, - the Irish in Canada, Ulster families, various professions etc. These include abstracts from various Irish Newspapers, including the Belfast Newsletter, which are printed below. Abstracts are included for all papers up to 1864, but excluding any entries in the Belfast Newsletter prior to 1801, as they are fully available online. Dr Smythe-Wood often found entries in several newspapers for the one event, & these will be shown as one entry below. Entries dealing with RIC Officers, Customs & Excise Officers, Coastguards, Prison Officers, & Irish families in Canada will be dealt with in separate files, although a small cache of Canadian entries is included here, being families closely associated with Co Tyrone. In most cases, Dr Smythe-Wood has recorded the exact entry, but in some, marked thus *, the entries were adjusted into a database, so should be treated with more caution. There are further large card indexes of Miscellaneous notes on families which are not at present being digitised, but which often deal with the same families treated below. ANC: Anglo-Celt LSL Londonderry Sentinel ARG Armagh Guardian LST Londonderry Standard/Derry Standard BAI Ballina Impartial LUR Lurgan Times BAU Banner of Ulster MAC Mayo Constitution -

Secretarys-Report-2006.Pdf

Coiste Thír Eoghain • An Chomhdháil Bhliantúil 2006 • Orduithe Seasaimh Don Chomhdháil • (Standing Orders For Convention) In order that the proceedings of the Convention be carried out without delay, the following Standing Orders will be observed: 1. The Proposer of a Resolution or of an Amendment thereto may speak for five minutes, but not more than five minutes. 2. A Delegate speaking to a Resolution or an Amendment must not exceed three minutes. 3. The Proposer of a Resolution or of an Amendment may speak a second time for three minutes before a vote is taken, but no other Delegate may speak a second time to the same Resolution or Amendment. 4. The Chairman may, at any time he considers a matter has been sufficiently discussed, call on the Proposer for a reply, and when that has been given a vote must be taken. 5. A Delegate may, with the consent of the Chairman, move ‘that the question be now put’, after which, when the Proposer has spoken, a vote must be taken. 6. Standing Orders shall not be suspended for the purpose of considering any matter not on the Clár, except by the consent of a majority equal to two-thirds of those present and voting. Tyrone Senior Team 2006 2 Coiste Thír Eoghain • An Chomhdháil Bhliantúil 2006 • Cumann Lúthchleas Gael Coiste Thír Eoghain • A Chara Tionólfár an Chomhdháil Bhliantúil de Chumann Lúthchleas Gael, Contae Thír Eoghain ar an Bearach (Cumann na Craoibhe Rua) ar an Máirt 12ú Nollaig 2006 ag tosnu ar 7.30 i.n. Mise, le fíor-mheas Damhnaic Mac Eochaidh Rúnaí • Clár • 1.