Sustainability Reporting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supply Chain Operations Audit

Building 243 University Campus Cranfield Bedford MK43 0AL Tel: +44 (0)1234 750323 Fax: +44 (0)1234 752040 www.scp-uk.co.uk Supply Chain Operations Audit by Dr. David Lascelles, Supply Chain Planning UK Limited High Impact Supply Chains Supply chain excellence has a real impact on business strategy. Supply chain management is a high impact mission that goes to the roots of a company’s very competitiveness. High-impact supply chains win market share and customer loyalty, create shareholder value, extend the strategic capability and reach of the business. Independent research shows that excellent supply chain management can yield: · 25-50% reduction in total supply chain costs · 25-60% reduction in inventory holding · 25-80% increase in forecast accuracy · 30-50% improvement in order-fulfilment cycle time · 20% increase in after-tax free cash flows That’s what we mean by high-impact. Does a high-impact supply chain leverage your business enterprise? Five Critical Success Factors Building a high-impact supply chain represents one of the most exciting opportunities to create value – and one of the most challenging. The key to success lies in knowing which levers to pull. Our research, together with practical experience, reveals that high-impact supply chains are, essentially, a function of five critical success factors: 1. A clear strategy: for the entire supply chain, tuned to market opportunities and focussed on customer service needs. 2. An integrated organisation structure: enabling the supply chain to operate as a single synchronised entity. 3. Excellent processes: for implementing the strategy, embracing all plan- source-make-deliver operations. -

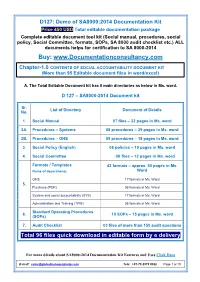

SA 8000:2014 Documents with Manual, Procedures, Audit Checklist

D127: Demo of SA8000:2014 Documentation Kit Price 450 USD Total editable documentation package Complete editable document tool kit (Social manual, procedures, social policy, Social Committee, formats, SOPs, SA 8000 audit checklist etc.) ALL documents helps for certification to SA 8000-2014 Buy: www.Documentationconsultancy.com Chapter-1.0 CONTENTS OF SOCIAL ACCOUNTABILITY DOCUMENT KIT (More than 95 Editable document files in word/excel) A. The Total Editable Document kit has 8 main directories as below in Ms. word. D 127 – SA8000-2014 Document kit Sr. List of Directory Document of Details No. 1. Social Manual 07 files – 22 pages in Ms. word 2A. Procedures – Systems 08 procedures – 29 pages in Ms. word 2B. Procedures – OHS 09 procedures – 18 pages in Ms. word 3. Social Policy (English) 08 policies – 10 pages in Ms. word 4. Social Committee 08 files – 12 pages in Ms. word Formats / Templates 43 formats – approx. 50 pages in Ms. Name of departments Word OHS 17 formats in Ms. Word 5. Purchase (PUR) 05 formats in Ms. Word System and social accountability (SYS) 17 formats in Ms. Word Administration and Training (TRG) 05 formats in Ms. Word Standard Operating Procedures 6. 10 SOPs – 15 pages in Ms. word (SOPs) 7. Audit Checklist 03 files of more than 150 audit questions Total 96 files quick download in editable form by e delivery For more détails about SA8000:2014 Documentation Kit Features and Uses Click Here E-mail: [email protected] Tele: +91-79-2979 5322 Page 1 of 10 D127: Demo of SA8000:2014 Documentation Kit Price 450 USD Total editable documentation package Complete editable document tool kit (Social manual, procedures, social policy, Social Committee, formats, SOPs, SA 8000 audit checklist etc.) ALL documents helps for certification to SA 8000-2014 Buy: www.Documentationconsultancy.com Part: B. -

Guide to Inspections of Quality Systems

FOOD AND DRUG ADMINISTRATION GUIDE TO INSPECTIONS OF QUALITY SYSTEMS 1 August 19991 2 Guide to Inspections of Quality Systems This document was developed by the Quality System Inspec- tions Reengineering Team Members Office of Regulatory Affairs Rob Ruff Georgia Layloff Denise Dion Norm Wong Center for Devices and Radiological Health Tim Wells – Team Leader Chris Nelson Cory Tylka Advisors Chet Reynolds Kim Trautman Allen Wynn Designed and Produced by Malaka C. Desroches 3 Foreword This document provides guidance to the FDA field staff on a new inspectional process that may be used to assess a medical device manufacturer’s compliance with the Quality System Regulation and related regulations. The new inspectional process is known as the “Quality System Inspection Technique” or “QSIT”. Field investigators may conduct an ef- ficient and effective comprehensive inspection using this guidance material which will help them focus on key elements of a firm’s quality system. Note: This manual is reference material for investi- gators and other FDA personnel. The document does not bind FDA and does not confer any rights, privi- leges, benefits or immunities4 for or on any person(s). Table of Contents Performing Subsystem Inspections. 7 Pre-announced Inspections. ..13 Getting Started. .15 Management Controls. .17 Inspectional Objectives 18 Decision Flow Chart 19 Narrative 20 Design Controls. .31 Inspectional Objectives 32 Decision Flow Chart 33 Narrative 34 Corrective and Preventive Actions (CAPA). .47 Inspectional Objectives 48 Decision Flow Chart 49 Narrative 50 Medical Device Reporting 61 Inspectional Objectives 62 Decision Flow Chart 63 Narrative 64 Corrections & Removals 67 Inspectional Objectives 68 Decision Flow Chart 69 Narrative 70 Medical Device Tracking 73 Inspectional Objectives 74 Decision Flow Chart 75 Narrative 76 Production and Process Controls (P&PC). -

Social Accounting: a Practical Guide for Small-Scale Community Organisations

Social Accounting: A Practical Guide for Small-Scale Community Organisations Social Accounting: A Practical Guide for Small Community Organisations and Enterprises Jenny Cameron Carly Gardner Jessica Veenhuyzen Centre for Urban and Regional Studies, The University of Newcastle, Australia. Version 2, July 2010 This page is intentionally blank for double-sided printing. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………..1 How this Guide Came About……………………………………………………2 WHAT IS SOCIAL ACCOUNTING?………………………………………………..3 Benefits.………………………………………………………………………....3 Challenges.……………………………………………………………………....4 THE STEPS………………………………………...…………………………………..5 Step 1: Scoping………………………………….………………………………6 Step 2: Accounting………………………………………………………………7 Step 3: Reporting and Responding…………………….……………………….14 APPLICATION I: THE BEANSTALK ORGANIC FOOD…………………….…16 APPLICATION II: FIG TREE COMMUNITY GARDEN…………………….…24 REFERENCES AND RESOURCES…………………………………...……………33 Acknowledgements We would like to thank The Beanstalk Organic Food and Fig Tree Community Garden for being such willing participants in this project. We particularly acknowledge the invaluable contribution of Rhyall Gordon and Katrina Hartwig from Beanstalk, and Craig Manhood and Bill Roberston from Fig Tree. Thanks also to Jo Barraket from the The Australian Centre of Philanthropy and Nonprofit Studies, Queensland University of Technology, and Gianni Zappalà and Lisa Waldron from the Westpac Foundation for their encouragement and for providing an opportunity for Jenny and Rhyall to present a draft version at the joint QUT and Westpac Foundation Social Evaluation Workshop in June 2010. Thanks to the participants for their feedback. Finally, thanks to John Pearce for introducing us to Social Accounting and Audit, and for providing encouragement and feedback on a draft version. While we have adopted the framework and approach to suit the context of small and primarily volunteer-based community organisations and enterprises, we hope that we have remained true to the intentions of Social Accounting and Audit. -

Chemical Management Audit Certification Supplier Management Verification Solutions

CHEMICAL MANAGEMENT AUDIT CERTIFICATION SUPPLIER MANAGEMENT VERIFICATION SOLUTIONS Intertek’s Chemical Management Audit solution is designed to help retailers and brands verify the safe handling and proper disposal of chemicals, in order to promote chemical management best practices throughout the global supply chain network. Your challenges, our solutions • Improved chemical management system unique techniques to best drive improvement Intertek’s Chemical Management Audit and practice through reduced environmental footprint, solution can help ensure effective chemical • Benchmarked results with global visibility increased efficiency and cost savings. management across your supply chain. The • Management transparency to enable This Chemical Management Audit is offered as process starts with an application of chemical targeted efforts. part of Intertek’s Supply Chain Solutions which expertise to provide a facility baseline risk help organizations all over the world manage • Identification of process efficiency and cost indicator, from which auditing of your facility compliance, risk, sustainability, and quality in savings can be efficiently planned. the supply chain. Intertek’s web-based platform and software • Assistance with green product design and helps ensure our Chemical Management certification Audit approach is the ideal tool for • Protect reputation risk, people and evaluating, tracking and monitoring chemical environment management performance in factories, Upon satisfactory completion of the chemical FOR MORE INFORMATION ultimately assuring overall performance management assessment and performance improvements. criteria, the manufacturer will receive a Intertek’s Chemical Management Audit report which details performance as well UK +44 116 296 1620 solution includes modular guidance for: as benchmarked comparisons with peers. The report showcases commitments of • Chemical Supply & Policy AMER +1 800 810 1195 moving towards zero discharge of hazardous • Management Practices chemicals. -

Conflict of Interest Program Audit December 6, 2019

City of Edmonton Office of the City Auditor Conflict of Interest Program Audit December 6, 2019 1200, Scotia Place, Tower 1 10060 Jasper Avenue Edmonton, AB T5J 3R8 Phone: 780-496-8300 edmonton.ca/auditor REPORT SUMMARY Conflict of Interest Program Audit 2019 Governance Framework The definition, principles, and roles and Recommendation: Update the responsibilities in the Code of Conduct related to corporate conflict of interest conflicts of interest need to be enhanced to provide governance framework. additional processes and accountabilities to ensure conflicts of interests are understood, prevented, detected, and remediated appropriately. Guiding Documents Recommendation: Develop Conflict of interest guidance is embedded in clear guiding documents the Code of Conduct guiding documents. These specific to conflict of interest documents do not provide clear guidance on that are tailored to the City’s how to manage the conflict of interest risks to needs and risks. which the City is vulnerable. Training and Communication Recommendations: Conflict of interest training is included in • Ensure all employees have Code of Conduct training. Current records completed the Code of Conduct show that 67% of City of Edmonton training upon hiring. employees have completed mandatory • Provide on-going conflict of Code of Conduct training. Conflict of interest communication, and interest information and tools are difficult accessible information and tools. to find. 1 Report Highlights Background .......................................................................... -

Practical Risk-Based Guide for Managing Data Integrity

1 ACTIVE PHARMACEUTICAL INGREDIENTS COMMITTEE Practical risk-based guide for managing data integrity Version 1, March 2019 2 PREAMBLE This original version of this guidance document has been compiled by a subdivision of the APIC Data Integrity Task Force on behalf of the Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient Committee (APIC) of CEFIC. The Task Force members are: Charles Gibbons, AbbVie, Ireland Danny De Scheemaecker, Janssen Pharmaceutica NV Rob De Proost, Janssen Pharmaceutica NV Dieter Vanderlinden, S.A. Ajinomoto Omnichem N.V. André van der Biezen, Aspen Oss B.V. Sebastian Fuchs, Tereos Daniel Davies, Lonza AG Fraser Strachan, DSM Bjorn Van Krevelen, Janssen Pharmaceutica NV Alessandro Fava, F.I.S. (Fabbrica Italiana Sintetici) SpA Alexandra Silva, Hovione FarmaCiencia SA Nicola Martone, DSM Sinochem Pharmaceuticals Ulrich-Andreas Opitz, Merck KGaA Dominique Rasewsky, Merck KGaA With support and review from: Pieter van der Hoeven, APIC, Belgium Francois Vandeweyer, Janssen Pharmaceutica NV Annick Bonneure, APIC, Belgium The APIC Quality Working Group 3 1 Contents 1. General Section .............................................................................................................................. 4 1.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 4 1.2 Objectives and Scope .............................................................................................................. 5 1.3 Definitions and abbreviations ................................................................................................ -

Social Accounting & Audit

Social Accounting & Audit Social accounting and audit (SAA) helps you prove, improve and account for the difference you are making. It can help an organisation to investigate its performance against social, environmental and economic objectives, and ensure that it is working in accordance with its values. It is a logical and flexible framework to understand the impact your organisation has on people, the planet and the way we use resources. It will also help to manage your organisation and improve your effectiveness. This framework is built on: Prove! - account fully for and report on your organisation’s social, environmental and economic performance and impact Improve! – provide the information essential for planning future actions and improving performance; and Account! – be accountable to all those you work with and work for… According to the Social Audit Network (SAN), a network providing assistance to third sector or social economy organisations throughout the UK and internationally, the key principles of social accounting are: Multi-perspective: encompassing the views of people and groups that are important to the organisation Comprehensive: inclusive of all activities of an organisation Comparative: able to be viewed in the light of other organisations and addressing the same issues within same organisation over time Regular: done on an ongoing basis at regular intervals Verified: checked by people external to the organisation Disclosed: readily available to others inside and outside of the organisation To get ready, you need to learn how Social Accounting works, what resources are required, decide how the process will be managed; and make an informed decision about whether to go forward. -

Greenwash: Corporate Environmental Disclosure Under Threat of Audit∗

Greenwash: Corporate Environmental Disclosure under Threat of Audit∗ Thomas P. Lyon†and John W. Maxwell‡ May 23, 2007 Abstract We present an economic model of greenwash, in which a firm strategi- cally discloses environmental information and a non-governmental organi- zation (NGO) may audit and penalize the firm for failing to fully disclose its environmental impacts. We show that disclosures increase when the likelihood of good environmental performance is lower. Firms with in- termediate levels of environmental performance are more likely to engage in greenwash. Under certain conditions, NGO punishment of greenwash induces the firm to become less rather than more forthcoming about its environmental performance. We also show that complementarities with NGO auditing may justify public policies encouraging firms to adopt en- vironmental management systems. 1Introduction The most notable environmental trend in recent years has been the shift away from traditional regulation and towards voluntary programs by government and industry. Thousands of firms participate in the Environmental Protec- tion Agency’s partnership programs, and many others participate in industry- led environmental programs such as those of the World Business Council for Sustainable Development, the Chicago Climate Exchange, and the American Chemistry Council’s “Responsible Care” program.1 However, there is growing scholarly concern that these programs fail to deliver meaningful environmental ∗We would like to thank Mike Baye, Rick Harbaugh, Charlie Kolstad, John Morgan, Michael Rauh, and participants in seminars at the American Economic Association meetings, Canadian Resource and Environmental Economics meetings, Dartmouth, Indiana University, Northwestern, UC Berkeley, UC Santa Barbara and University of Florida for their helpful comments. -

Preparing Your Accounting Records for Audit

© Tony Abeyta PREPARING YOUR ACCOUNTING RECORDS Presented by: FOR AUDIT James Montoya INTRODUCTION James Montoya, CPA — Principal . 20 years providing audit and consulting services . Have provided audit or accounting services to over 120 entities, primarily tribal governments and related entities . Work with a team of accounting specialists that specialize in providing audit preparation accounting services . Have served as the board Treasurer for three organizations and as a board member on another 2 TRIBAL GOVERNMENT AUDIT EXPERIENCE (2016 AUDITED FEDERAL EXPENDITURES BY AUDIT FIRM) Total: $7B in Native American Federal Award Expenditures $890 $576 $559 $530 $442 $384 $341 $269 $260 $187 REDW KPMP Stauffer BKD Moss Adams BDO RSM CLA Joseph Eve Bluebird Millions $890 $576 $559 $530 $442 $384 $341 $269 $260 $187 * Source: 2016 Federal Audit Clearinghouse Data (as of 11/20/17) 4 SESSION TOPICS . Overview of types of financial statements . Provide target timelines for issuing the financial statements . Describe goals for issuing reports timely, receiving unmodified opinions and minimizing audit findings . Techniques to effectively prepare for your audits . Software tools to manage month-end close processes . Common areas that require additional attention . Q&A OBJECTIVES OF PREPARING FOR AN ANNUAL FINANCIAL AUDIT Provide Auditors with Ensure Adequate Information Needed Minimize Audit Accounting Records for a Timely and Findings and Internal Are Maintained Efficient Audit Control Deficiencies Understand Internal Minimize the Control Processes Effectively Disruption to Daily Needing Communicate Results Responsibilities Improvement to Governing Body COMMON TYPES OF TRIBAL GOVERNMENT FINANCIAL STATEMENT REPORTS 1. Audited Financial Statements of Individual Funds, Component Units and Special-purpose Governments – Examples include enterprise funds, housing authorities, tribal schools, etc. -

Auditor-Client Conflicts of Interest

Submission dated 28 October 2019 Parliamentary Joint Committee on Corporations and Financial Services: Regulation of Auditing in Australia By certifying the public reports that collectively depict a corporation’s financial status, the independent auditor assumes a public responsibility transcending any employment relationship with the client. The independent public accountant performing this special function owes ultimate allegiance to the corporation's creditors and stockholders, as well as to the investing public. This "public watchdog" function demands that the accountant maintain total independence from the client at all times and requires complete fidelity to the public trust. - Chief Justice Warren Burger, writing on behalf of a unanimous United States Supreme Court in the case of United States v. Arthur Young & Co. (1984) Auditor-client conflicts of interest In corporate Australia it is the client, not the creditors, stockholders or investing public, who pays, hires and fires the ‘independent’ auditor. Yet it is to the public trust that the auditor owes complete fidelity. In these circumstances can the auditor maintain total independence from the client? University research, referred to below, suggests not. The Joint Accounting Bodies Independence Guide (‘the Guide’) is, ‘intended to assist professional accountants in understanding and applying the auditor independence requirements of the APES 110 Code of Ethics for Professional Accountants (the Code) issued by the Accounting Professional & Ethical Standards Board’.1 The Guide states: In today’s competitive world trust and confidence are essential to the stability of capital markets. The auditing profession plays a critical role in the orderly functioning of capital markets by performing independent audits. The independence of the auditor is crucial to this process and helps to build the trust of shareholders, regulators and other stakeholders in financial information which has been subject to audit.. -

The Importance of Sustainability Audit Report in Go Public Companies Sector, in Indonesia

Advances in Science, Technology and Engineering Systems Journal Vol. 5, No. 4, 217-222 (2020) ASTESJ www.astesj.com ISSN: 2415-6698 The Importance of Sustainability Audit Report in Go Public Companies Sector, in Indonesia Bambang Leo Handoko*, Ang Swat Lin Lindawati Accounting Department, Faculty of Economics and Communication, Bina Nusantara University, Jakarta, 11480, Indonesia A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Article history: Sustainability is considered new for Indonesian state-owned enterprises, also has become Received: 09 April, 2020 an obligation since two years ago. More and more people are aware of the environment for Accepted: 07 July, 2020 the next generation, the survival of mankind in the future. Sustainability issues are no Online: 22 July, 2020 exception in Indonesia. Companies publish sustainability reports as well as financial and annual reports. This sustainability report creates a need, namely the need for audits for Keywords: sustainability reports. This is often referred to as a sustainability audit or assurance report. Sustainability It is a qualitative descriptive survey. Researchers collect data from the literature and study Reporting observations as well as from interviews with stakeholders. The results of our study were Audit obtained because the increasing number of public companies reporting on sustainability Indonesia requires sustainability reporting audits in Indonesian public companies. The advantage of Corporation a sustainability audit report is that, in addition to its reputation or image, it can also add value to the company's planning, structure and accountability. Brand name of the listed company. However, there are weaknesses, the weakness lies in comparability and costs.