Range, Trends and Conservation Status

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sino-Himalayan Mountain Forests (PDF, 760

Sino-Himalayan mountain forests F04 F04 Threatened species HIS region is made up of the mid- and high-elevation forests, Tscrub and grasslands that cloak the southern slopes of the CR EN VU Total Himalayas and the mountains of south-west China and northern 1 1 1 26 28 Indochina. A total of 28 threatened species are confined (as breeding birds) to the Sino-Himalayan mountain forests, including six which ———— are relatively widespread in distribution, and 22 which inhabit one of the region’s six Endemic Bird Areas: Western Himalayas, Eastern Total 1 1 26 28 Himalayas, Shanxi mountains, Central Sichuan mountains, West Key: = breeds only in this forest region. Sichuan mountains and Yunnan mountains. All 28 taxa are 1 Three species which nest only in this forest considered Vulnerable, apart from the Endangered White-browed region migrate to other regions outside the breeding season, Wood Snipe, Rufous- Nuthatch, which has a tiny range, and the Critically Endangered headed Robin and Kashmir Flycatcher. Himalayan Quail, which has not been seen for over a century and = also breeds in other region(s). may be extinct. The Sino-Himalayan mountain forests region includes Conservation International’s South- ■ Key habitats Montane temperate, subtropical and subalpine central China mountains Hotspot (see pp.20–21). forest, and associated grassland and scrub. ■ Altitude 350–4,500 m. ■ Countries and territories China (Tibet, Qinghai, Gansu, Sichuan, Yunnan, Guizhou, Shaanxi, Shanxi, Hebei, Beijing, Guangxi); Pakistan; India (Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Uttaranchal, West Bengal, Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Meghalaya, Nagaland, Manipur, Mizoram); Nepal; Bhutan; Myanmar; Thailand; Laos; Vietnam. -

A Study on Avifauna Present in Different Zones of Chitral Districts

Journal of Bioresource Management Volume 4 Issue 1 Article 4 A Study on Avifauna Present in Different Zones of Chitral Districts Madeeha Manzoor Center for Bioresource Research Adila Nazli Center for Bioresource Research, [email protected] Sabiha Shamim Center for Bioresource Research Fida Muhammad Khan Center for Bioresource Research Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/jbm Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Manzoor, M., Nazli, A., Shamim, S., & Khan, F. M. (2017). A Study on Avifauna Present in Different Zones of Chitral Districts, Journal of Bioresource Management, 4 (1). DOI: 10.35691/JBM.7102.0067 ISSN: 2309-3854 online (Received: May 29, 2019; Accepted: May 29, 2019; Published: Jan 1, 2017) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Bioresource Management by an authorized editor of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Study on Avifauna Present in Different Zones of Chitral Districts Erratum Added the complete list of author names © Copyrights of all the papers published in Journal of Bioresource Management are with its publisher, Center for Bioresource Research (CBR) Islamabad, Pakistan. This permits anyone to copy, redistribute, remix, transmit and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes provided the original work and source is appropriately cited. Journal of Bioresource Management does not grant you any other rights in relation to this website or the material on this website. In other words, all other rights are reserved. For the avoidance of doubt, you must not adapt, edit, change, transform, publish, republish, distribute, redistribute, broadcast, rebroadcast or show or play in public this website or the material on this website (in any form or media) without appropriately and conspicuously citing the original work and source or Journal of Bioresource Management’s prior written permission. -

"Official Gazette of RM", No. 28/04 and 37/07), the Government of the Republic of Montenegro, at Its Meeting Held on ______2007, Enacted This

In accordance with Article 6 paragraph 3 of the FT Law ("Official Gazette of RM", No. 28/04 and 37/07), the Government of the Republic of Montenegro, at its meeting held on ____________ 2007, enacted this DECISION ON CONTROL LIST FOR EXPORT, IMPORT AND TRANSIT OF GOODS Article 1 The goods that are being exported, imported and goods in transit procedure, shall be classified into the forms of export, import and transit, specifically: free export, import and transit and export, import and transit based on a license. The goods referred to in paragraph 1 of this Article were identified in the Control List for Export, Import and Transit of Goods that has been printed together with this Decision and constitutes an integral part hereof (Exhibit 1). Article 2 In the Control List, the goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license, were designated by the abbreviation: “D”, and automatic license were designated by abbreviation “AD”. The goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license designated by the abbreviation “D” and specific number, license is issued by following state authorities: - D1: the goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license issued by the state authority competent for protection of human health - D2: the goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license issued by the state authority competent for animal and plant health protection, if goods are imported, exported or in transit for veterinary or phyto-sanitary purposes - D3: the goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license issued by the state authority competent for environment protection - D4: the goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license issued by the state authority competent for culture. -

Prelims Booster Compilation

PRELIMS BOOSTER 1 INSIGHTS ON INDIA PRELIMS BOOSTER 2018 www.insightsonindia.com WWW.INSIGHTSIAS.COM PRELIMS BOOSTER 2 Table of Contents Northern goshawk ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Barasingha (swamp deer or dolhorina (Assam)) ..................................................................................... 4 Blyth’s tragopan (Tragopan blythii, grey-bellied tragopan) .................................................................... 5 Western tragopan (western horned tragopan ) ....................................................................................... 6 Black francolin (Francolinus francolinus) ................................................................................................. 6 Sarus crane (Antigone antigone) ............................................................................................................... 7 Himalayan monal (Impeyan monal, Impeyan pheasant) ......................................................................... 8 Common hill myna (Gracula religiosa, Mynha) ......................................................................................... 8 Mrs. Hume’s pheasant (Hume’s pheasant or bar-tailed pheasant) ......................................................... 9 Baer’s pochard ............................................................................................................................................. 9 Forest Owlet (Heteroglaux blewitti) ....................................................................................................... -

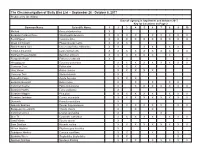

The Circumnavigation of Sicily Bird List -- September 26

The Circumnavigation of Sicily Bird List -- September 26 - October 8, 2017 Produced by Jim Wilson Date of sighting in September and October 2017 Key for Locations on Page 2 Common Name Scientific Name 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Mallard Anas platyrhynchos X Eurasian Collared Dove Streptopelia decaocto X X X X X X X X X Feral Pigeon Columba livia X X X X X X X X X X Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo X X X Black-headed Gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus X X X X X X Yellow-legged Gull Larus michahellis X X X X X X X X X X Northern House Martin Delichon urbicum X X X X X X X European Robin Erithacus rubecula X X Woodpigeon Columba palumbus X X X X X X X X X Common Coot Fulica atra X X X Grey Heron Ardea cinerea X X X X X Common Tern Sterna hirundo X Bonnelli's Eagle Aquila fasciata X X X Eurasian Buzzard Buteo buteo X X X X X Common Kestrel Falco tinnunculus X X X X X X X X Eurasian Hobby Falco subbuteo X Eurasian Magpie Pica pica X X X X X X X X Eurasian Jackdaw Corvus monedula X X X X X X X X X Dunnock Prunella modularis X Spanish Sparrow Passer hispaniolensis X X X X X X X X European Greenfinch Chloris chloris X X X Common Linnet Linaria cannabina X X Blue Tit Cyanistes caeruleus X X X X X X X X Sand Martin Riparia riparia X Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica X X X X X X X X X Willow Warbler Phylloscopus trochilus X Subalpine Warbler Curruca cantillans X X X X Eurasian Wren Troglodytes troglodytes X X X Spotless Starling Spotless Starling X X X X X X X X Common Name Scientific Name 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Sardinian Warbler Curruca melanocephala X X X X -

Status and Phylogenetic Analyses of Endemic Birds of the Himalayan Region

Pakistan J. Zool., vol. 47(2), pp. 417-426, 2015. Status and Phylogenetic Analyses of Endemic Birds of the Himalayan Region M.L. Thakur* and Vineet Negi Himachal Pradesh State Biodiversity Board; Department of Environment, Science & Technology, Shimla-171 002 (HP), India Abstract.- Status and distribution of 35 species of birds endemic to Himalayas has been analysed during the present effort. Of these, relatively very high percentage i.e. 46% (16 species) is placed under different threat categories. Population of 24 species (74%) is decreasing. A very high percentage of these Himalayan endemics (88%) are dependent on forests. Population size of most of these bird species (22 species) is not known. Population size of some bird species is very small. Distribution area size of some of the species is also very small. Three species of endemic birds viz., Callacanthis burtoni, Pyrrhula aurantiaca and Pnoepyga immaculata appear to have followed some independent evolutionary lineage and also remained comparatively stable over the period of time. Three different evolutionary clades of the endemic bird species have been observed on the basis of phylogenetic tree analyses. Analyses of length of branches of the phylogenetic tree showed that the three latest entries in endemic bird fauna of Himalayan region i.e. Catreus wallichii, Lophophorus sclateri and Tragopan blythii have been categorised as vulnerable and therefore need the highest level of protection. Key Words: Endemic birds, Himalayan region, conservation status, phylogeny. INTRODUCTION broadleaved forests in the mid hills, mixed conifer and coniferous forests in the higher hills, and alpine meadows above the treeline mainly due to abrupt The Himalayas, one of the hotspots of rise of the Himalayan mountains from less than 500 biodiversity, include all of the world's mountain meters to more than 8,000 meters (Conservation peaks higher than 8,000 meters, are stretched in an International, 2012). -

TRAFFIC POST Galliformes in Illegal Wildlife Trade in India: a Bird's Eye View in FOCUS TRAFFIC Post

T R A F F I C NEWSLETTER ON WILDLIFE TRADE IN INDIA N E W S L E T T E R Issue 29 SPECIAL ISSUE ON BIRDS MAY 2018 TRAFFIC POST Galliformes in illegal wildlife trade in India: A bird's eye view IN FOCUS TRAFFIC Post TRAFFIC’s newsletter on wildlife trade in India was started in September 2007 with a primary objective to create awareness about poaching and illegal wildlife trade . Illegal wildlife trade is reportedly the fourth largest global illegal trade after narcotics, counterfeiting and human trafficking. It has evolved into an organized activity threatening the future of many wildlife species. TRAFFIC Post was born out of the need to reach out to various stakeholders including decision makers, enforcement officials, judiciary and consumers about the extent of illegal wildlife trade in India and the damaging effect it could be having on the endangered flora and fauna. Since its inception, TRAFFIC Post has highlighted pressing issues related to illegal wildlife trade in India and globally, flagged early trends, and illuminated wildlife policies and laws. It has also focused on the status of legal trade in various medicinal plant and timber species that need sustainable management for ensuring ecological and economic success. TRAFFIC Post comes out three times in the year and is available both online and in print. You can subscribe to it by writing to [email protected] All issues of TRAFFIC Post can be viewed at www.trafficindia.org; www.traffic.org Map Disclaimer: The designations of the geographical entities in this publication and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WWF-India or TRAFFIC concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

ZSL National Red List of Nepal's Birds Volume 5

The Status of Nepal's Birds: The National Red List Series Volume 5 Published by: The Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London, NW1 4RY, UK Copyright: ©Zoological Society of London and Contributors 2016. All Rights reserved. The use and reproduction of any part of this publication is welcomed for non-commercial purposes only, provided that the source is acknowledged. ISBN: 978-0-900881-75-6 Citation: Inskipp C., Baral H. S., Phuyal S., Bhatt T. R., Khatiwada M., Inskipp, T, Khatiwada A., Gurung S., Singh P. B., Murray L., Poudyal L. and Amin R. (2016) The status of Nepal's Birds: The national red list series. Zoological Society of London, UK. Keywords: Nepal, biodiversity, threatened species, conservation, birds, Red List. Front Cover Back Cover Otus bakkamoena Aceros nipalensis A pair of Collared Scops Owls; owls are A pair of Rufous-necked Hornbills; species highly threatened especially by persecution Hodgson first described for science Raj Man Singh / Brian Hodgson and sadly now extinct in Nepal. Raj Man Singh / Brian Hodgson The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of participating organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of any participating organizations. Notes on front and back cover design: The watercolours reproduced on the covers and within this book are taken from the notebooks of Brian Houghton Hodgson (1800-1894). -

![Explorer Research Article [Tripathi Et Al., 6(3): March, 2015:4304-4316] CODEN (USA): IJPLCP ISSN: 0976-7126 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL of PHARMACY & LIFE SCIENCES (Int](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4638/explorer-research-article-tripathi-et-al-6-3-march-2015-4304-4316-coden-usa-ijplcp-issn-0976-7126-international-journal-of-pharmacy-life-sciences-int-1074638.webp)

Explorer Research Article [Tripathi Et Al., 6(3): March, 2015:4304-4316] CODEN (USA): IJPLCP ISSN: 0976-7126 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL of PHARMACY & LIFE SCIENCES (Int

Explorer Research Article [Tripathi et al., 6(3): March, 2015:4304-4316] CODEN (USA): IJPLCP ISSN: 0976-7126 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PHARMACY & LIFE SCIENCES (Int. J. of Pharm. Life Sci.) Study on Bird Diversity of Chuhiya Forest, District Rewa, Madhya Pradesh, India Praneeta Tripathi1*, Amit Tiwari2, Shivesh Pratap Singh1 and Shirish Agnihotri3 1, Department of Zoology, Govt. P.G. College, Satna, (MP) - India 2, Department of Zoology, Govt. T.R.S. College, Rewa, (MP) - India 3, Research Officer, Fishermen Welfare and Fisheries Development Department, Bhopal, (MP) - India Abstract One hundred and twenty two species of birds belonging to 19 orders, 53 families and 101 genera were recorded at Chuhiya Forest, Rewa, Madhya Pradesh, India from all the three seasons. Out of these as per IUCN red list status 1 species is Critically Endangered, 3 each are Vulnerable and Near Threatened and rest are under Least concern category. Bird species, Gyps bengalensis, which is comes under Falconiformes order and Accipitridae family are critically endangered. The study area provide diverse habitat in the form of dense forest and agricultural land. Rose- ringed Parakeets, Alexandrine Parakeets, Common Babblers, Common Myna, Jungle Myna, Baya Weavers, House Sparrows, Paddyfield Pipit, White-throated Munia, White-bellied Drongo, House crows, Philippine Crows, Paddyfield Warbler etc. were prominent bird species of the study area, which are adapted to diversified habitat of Chuhiya Forest. Human impacts such as Installation of industrial units, cutting of trees, use of insecticides in agricultural practices are major threats to bird communities. Key-Words: Bird, Chuhiya Forest, IUCN, Endangered Introduction Birds (class-Aves) are feathered, winged, two-legged, Birds are ideal bio-indicators and useful models for warm-blooded, egg-laying vertebrates. -

Seasonal Variation in Nest Mass and Dimensions in an Open-Cup Ground-Nesting Shrub-Steppe Passerine: the Tawny Pipit Anthus Campestris

Ardeola 52(1), 2005, 43-51 SEASONAL VARIATION IN NEST MASS AND DIMENSIONS IN AN OPEN-CUP GROUND-NESTING SHRUB-STEPPE PASSERINE: THE TAWNY PIPIT ANTHUS CAMPESTRIS Francisco SUÁREZ*, Manuel B. MORALES* 1, Israel MÍNGUEZ* & Jesús HERRANZ* SUMMARY.—SUMMARY.- Seasonal variation in nest mass and dimensions in an open-cup ground nesting shrub-steppe passerine: The Tawny Pipit Anthus campestris. Aims: The main aim was to study seasonal variation in the mass and dimensions of nests of Tawny Pipits Anthus campestris. Location: The study was conducted in Layna (Soria). Methods: Seasonal variation in the mass and dimensions of 88 nests of Tawny Pipits was studied over five years. The data were evaluated against five hypotheses (involving predation, clutch size, incubatory efficiency, thermoregulation and sexual selection). Results: The probability of predation was unrelated to outer nest diameter nor was there any relationship bet- ween internal diameter and the presence of unhatched eggs. Wall thickness and nest mass declined as the se- ason progressed but there was no relationship between these variables and the mean environmental tempe- rature during either seven or four days preceding the start of nest building. Clutch size did not correlate with outer nest diameter nor with nest mass but was positively related to nest volume. Conclusions: It is concluded that the clutch size hypothesis, in which females are capable of adjusting nest size to clutch size, best explains the observed variation. This is the first demonstration of the applicabi- lity of this hypothesis to a ground-nesting, open-cup nest building species. Key words: Motacillidae, clutch size, nest size variation, clutch size hypothesis, Tawny Pipit, Anthus campestris. -

Conservation of Breeding Colonies of the Bank Myna, Acridotheres Ginginianus (Latham 1790), in Chapai Nawabganj, Bangladesh

Univ. j. zool. Rajshahi Univ. Vol. 30, 2011 pp. 49-53 ISSN 1023-6104 http://journals.sfu.ca/bd/index.php/UJZRU © Rajshahi University Zoological Society Conservation of breeding colonies of the bank myna, Acridotheres ginginianus (Latham 1790), in Chapai Nawabganj, Bangladesh M Farid Ahsan and M Tarik Kabir Department of Zoology, University of Chittagong, Chittagong, Bangladesh Abstact: A study on the conservation on breeding colonies of bank myna, Acridotheres ginginianus (Latham 1790), was conducted in Chapai Nawabganj district of Bangladesh during a period from June 2007 to October 2009. The total population in the breeding colonies was estimated as 4,452. The preferable breeding habitats of bird are bank of the river, soil heap/ditches of brickfield and holes of culvert. Environmental calamities such as bank erosion and flooding, drought and rain affect the breeding colonies. Human settlement near breeding habitats, hunting, collecting eggs and nestlings by children, and use of nets to prevent nesting at bank of the river are the main human impacts on the breeding colonies. Major threats are flood, children-fun, predators and human for its meat. Conservation awareness for this species have depicted in this paper. Key words: Conservation, breeding colonies, bank myna, Acridotheres ginginianus, Chapai Nawabganj, Bangladesh. example, Grimmett et al. (1998), Inskipp et al. Introduction (1996), Sibley & Monroe (1993, 1990), Sibley & Conservation biology is the new multidisciplinary Ahlquist (1990), Ripley (1982), Husain (2003, science that -

Sturnus Roseus

Report under the Article 12 of the Birds Directive European Environment Agency Period 2008-2012 European Topic Centre on Biological Diversity Sturnus roseus Annex I No International action plan No Rosy Starling, Sturnus roseus, is a species of passerine bird in the starling family found in heathland and shrub and unvegetated or sparsely vegetated land ecosystems. Sturnus roseus has a breeding population size of 260-32300 pairs and a breeding range size of 3700 square kilometres in the EU27. The breeding population trend in the EU27 is Unknown in the short term and Unknown in the long term. The EU population status for Sturnus roseus is Unknown, as the data reported were not sufficient to assess the population status of the species. Page 1 Sturnus roseus Report under the Article 12 of the Birds Directive Assessment of status at the European level Breeding Breeding range Winter population Winter Breeding population trend Range trend trend Population population population size area status Short Long Short Long size Short Long term term term term term term 260 - 32300 p x x 3700 Unknown See the endnotes for more informationi Page 2 Sturnus roseus Report under the Article 12 of the Birds Directive Page 3 Sturnus roseus Report under the Article 12 of the Birds Directive Trends at the Member State level Breeding Breeding range Winter population Winter % in Breeding population trend Range trend trend MS/Ter. population EU27 population size area Short Long Short Long size Short Long term term term term term term BG 53.3 10 - 7300 p F F 1600 F F GR RO 46.7 250 - 24000 p x x 2100 x x See the endnotes for more informationii Page 4 Sturnus roseus Report under the Article 12 of the Birds Directive Page 5 Sturnus roseus Report under the Article 12 of the Birds Directive Short-term winter population trend was not reported for this species.