Tissue Donation Potential Beyond Acute Care

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open 1-Megan Shivy Thesis.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF SUPPLY CHAIN AND INFORMATION SYSTEMS THE OPTIMIZATION OF ORGAN TRANSPLANTATION MEGAN KAITLAN SHIVY SPRING 2015 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in Supply Chain and Information Systems with honors in Supply Chain and Information Systems Reviewed and approved* by the following: Robert Novack Associate Professor of Supply Chain Management Thesis Supervisor John Spychalski Professor Emeritus of Supply Chain Management Honors Adviser * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT The purpose of this thesis is to give a high level overview of the supply chain process associated with organ transplantation in the United Sates. Using information on organ transplantation programs from other areas of the world coupled with input from transplant expertise this thesis will highlight areas for logistical improvement to improve the success rate of organ transplantation in the United States. This thesis concluded that while the ultimate solution of improving the success rate of organ transplantation may take legislative action, standardization of transportation by organ is a viable option to save the lives of people waiting for life saving transplants. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ..................................................................................................... iii LIST OF TABLES ...................................................................................................... -

Animal-To-Human Transplantation: Should Canada Proceed?

Animal-to-human transplantation: Should Canada proceed? A public consultation on xenotransplantation Canadian Public Health Association Animal-to-human transplantation: Should Canada proceed? A public consultation on xenotransplantation © December 2001 by the Canadian Public Health Association Permission is granted for non-commercial reproduction only, provided there is a clear acknowledgement of the source. ISBN 1-894324-20-X Canadian Public Health Association 400-1565 Carling Avenue Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, K1Z 8R1 CPHA’s Mission Statement The Canadian Public Health Association (CPHA) is a national, independent, not-for- profit, voluntary association representing public health in Canada with links to the international public health community. CPHA’s members believe in universal and equitable access to the basic conditions which are necessary to achieve health for all Canadians. CPHA’s mission is to constitute a special national resource in Canada that advocates for the improvement and maintenance of personal and community health according to the public health principles of disease prevention, health promotion and protection, and healthy public policy. This consultation was funded by Health Canada. The views expressed in this report are those of the Public Advisory Group, and are based on consultations with a broad sector of the Canadian public. They do not necessarily represent the official policy or views of Health Canada or the Canadian Public Health Association. The English and French reports and executive summaries are available on the consultation website at http://www.xeno.cpha.ca or through http://www.cpha.ca. French translation by Sylvie Lee January 7, 2002 The Honourable Allan Rock Minister of Health Brooke Claxton Building, Tunney’s Pasture Ottawa, Ontario, K1A 0K9 Dear Minister Rock: It is our pleasure to provide you with the report Animal-to-human transplantation: Should Canada proceed? This report documents the results of a comprehensive consultation with Canadians on the complex issue of xenotransplantation. -

Partnering with Your Transplant Team the Patient’S Guide to Transplantation

Partnering With Your Transplant Team The Patient’s Guide to Transplantation U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Health Resources and Services Administration This booklet was prepared for the Health Resources and Services Administration, Healthcare Systems Bureau, Division of Transplantation by the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS). PARTNERING WITH YOUR TRANSPLANT TEAM THE PATIENT’S GUIDE TO TRANSPLANTATION U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Health Resources and Services Administration Public Domain Notice All material appearing in this document, with the exception of AHA’s The Patient Care Partnership: Understanding Expectations, Rights and Responsibilities, is in the public domain and may be reproduced without permission from HRSA. Citation of the source is appreciated. Recommended Citation U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2008). Partnering With Your Transplant Team: The Patient’s Guide to Transplantation. Rockville, MD: Health Resources and Services Administration, Healthcare Systems Bureau, Division of Transplantation. DEDICATION This book is dedicated to organ donors and their families. Their decision to donate has given hundreds of thousands of patients a second chance at life. CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION.........................................................................................................................1 THE TRANSPLANT EXPERIENCE .........................................................................................3 The Transplant Team .......................................................................................................................4 -

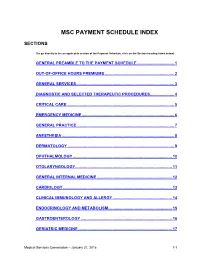

Msc Payment Schedule Index

MSC PAYMENT SCHEDULE INDEX SECTIONS (To go directly to the an applicable section of the Payment Schedule, click on the Section heading listed below) GENERAL PREAMBLE TO THE PAYMENT SCHEDULE .................................. 1 2. OUT-OF-OFFICE HOURS PREMIUMS ............................................................... 2 3. GENERAL SERVICES ......................................................................................... 3 4. DIAGNOSTIC AND SELECTED THERAPEUTIC PROCEDURES ...................... 4 5. CRITICAL CARE .................................................................................................. 5 6. EMERGENCY MEDICINE .................................................................................... 6 7. GENERAL PRACTICE ......................................................................................... 7 8. ANESTHESIA ...................................................................................................... 8 9. DERMATOLOGY ................................................................................................. 9 10. OPHTHALMOLOGY .......................................................................................... 10 11. OTOLARYNGOLOGY ........................................................................................ 11 12. GENERAL INTERNAL MEDICINE .................................................................... 12 13. CARDIOLOGY ................................................................................................... 13 14. CLINICAL IMMUNOLOGY AND ALLERGY -

Chronic Hepatitis C Viral Infection: Natural History and Treatment Outcomes in Substance Abusers

Chronic Hepatitis C Viral Infection: Natural History and Treatment Outcomes in Substance Abusers by Ava Ayana John-Baptiste A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation University of Toronto © Copyright by Ava Ayana John-Baptiste, 2010 Chronic Hepatitis C Viral Infection: Natural History and Treatment Outcomes in Substance Abusers Ava Ayana John-Baptiste Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation University of Toronto 2010 Abstract Hepatitis C is the most common blood-borne viral illness in the North America. Chronic hepatitis C infection may lead to cirrhosis of the liver, liver failure and liver cancer. In North America, injection drug use is the most important risk factor for infection and substance abusing populations are disproportionately affected by the disease. Antiviral therapy exists and approximately 50% of infected individuals can be cured. The aim of this thesis was to provide information to help clinicians and policy-makers minimize the impact of hepatitis C in substance abusers. The thesis is comprised of three studies. The first assessed the rate of progression to cirrhosis for those acquiring infection through injection drug use, using a meta-analysis of 44 studies from the published literature. We estimated that fibrosis progression occurs at a rate of 8.1 per 1000 person-years (95% Credible Region (CR), 3.9 to 14.7) corresponding to a 20-year cirrhosis prevalence of 14.8% (95% CR, 7.5 to 25.5). The second study measured the association between successful antiviral therapy and quality of life. -

Organ Utilization Among Deceased Donors in Canada, 1993–

838 NEUROANESTHESIACANADIAN JOURNAL AND OFINTENSIVE ANESTHESIA CARE Organ utilization among deceased donors in Canada, 1993–2002 [L’utilisation d’organes de donneurs décédés au Canada de 1993 à 2002] Kim Badovinac MA MBA,* Paul D. Greig MD FRCS(C),† Heather Ross MD MHSc FRCPC,‡ Christopher J. Doig MD MSc FRCPC,§ Sam D. Shemie MD¶ Background: Optimizing organ utilization from consented Contexte : Optimaliser l’utilisation d’organes de donneurs con- donors is a critical need, given a static organ donation rate. We sentants est une véritable nécessité, étant donné la stabilité actu- report changes in the characteristics of donors and organ utili- elle du taux de don d’organes. Nous présentons les caractéristiques zation patterns in Canada over a ten-year period. des donneurs et de l’utilisation des organes au Canada au cours Methods: For the decade spanning the years 1993–2002, data d’une décennie. were extracted from the Canadian Organ Replacement Register Méthode : Pour la décennie 1993-2202, les données ont été (CORR), the national transplant registry. A donor was defined extraites du Registre canadien des insuffisances et des transplan- as a deceased person from whom at least one vital organ was tations d’organes (RCITO). Un donneur était défini comme une retrieved and transplanted. personne décédée chez qui un organe au moins était prélevé et Results: The donor pool is aging (median age of donors transplanté. increased eight years over the decade), with proportionately Résultats : Le pool de donneurs est âgé (l’âge moyen a augmenté fewer donors dying from head trauma (motor vehicle collisions) de huit ans pendant la décennie) et il y a proportionnellement and proportionately more from cerebrovascular accidents. -

Lung Transplant

Lung Transplant Information for Alberta & NWT Residents Disclaimer The information in this booklet is a guide and is meant to support the information given to you by your healthcare professionals. All information was current at the time of printing but things can and do change. The transplant centre team will provide much more information about lung transplants once a person is referred for assessment. c o n t e n t s 4 Introduction 6 The Basics of Breathing 7 General Transplant Information 9 Your Questions Answered 17 Becoming a Lung Transplant Candidate 21 The Costs of a Lung Transplant 27 Resources 30 Funding Uninsured Costs 35 Other Things to Consider 39 End of Life and Legal Decisions 42 Glossary of Lung Diseases 45 Planning Checklist 48 Notes 3 i n t r o d u c t i o n For those suffering from severe lung disease, having a lung transplant may be their only option to survive. This can be intimidating and at the same time it can be difficult to acquire qualified information to help make informed decisions regarding treatment. If you have been told that you need a lung transplant (or may need one in the future), you likely have many questions about what happens next. Not knowing what to expect can create a lot of fear and worry. This booklet is available to supplement the information available from other sources; more detailed or individually relevent information would be provided to you from the transplant team should you move forward with needing a lung transplant. There are currently five hospitals in Canada that perform lung transplants. -

Transplantation the Official Journal of the Transplantation Society

Supplement to June 15, 2011 ா Volume 91 Number 11S Transplantation The Official Journal of the Transplantation Society www.transplantjournal.com Contents - Note from the Secretariat ................................................... S27 - The Madrid Resolution on Organ Donation and Transplantation .................... S29 - Executive Summary ....................................................... S32 - Report of the Madrid Consultation Part 1: European and Universal Challenges in Organ Donation and Transplantation, Searching for Global Solutions ................... S39 - Report of the Madrid Consultation Part 2: Reports from the Working Groups ......... S67 - Working Group 1: Assessing Needs for Transplantation........................... S67 - Working Group 2: System Requirements for the Pursuit of Self-Sufficiency ........... S71 - Working Group 3: Meeting Needs through Donation ............................. S73 - Working Group 4: Monitoring Outcomes in the Pursuit of Self-Sufficiency ........... S75 - Working Group 5: Fostering Professional Ownership of Self-Sufficiency in the Emergency Department and Intensive Care Unit ........................................ S80 - Working Group 6: The Role of Public Health and Society in the Pursuit of Self-Sufficiency ........................................................ S82 - Working Group 7: Ethics of the Pursuit of Self-Sufficiency ......................... S87 - Working Group 8: Effectiveness in the Pursuit of Self-Sufficiency - Achievements and Opportunities ......................................................... -

Providing Better Access to Organs: a Comprehensive Overview of Organ-Access Initiatives from the ASTS PROACTOR Task Force

Received: 9 February 2017 | Revised: 25 June 2017 | Accepted: 13 July 2017 DOI: 10.1111/ajt.14441 SPECIAL ARTICLE PROviding Better ACcess To ORgans: A comprehensive overview of organ- access initiatives from the ASTS PROACTOR Task Force M. J. Hobeika1 | C. M. Miller2 | T. L. Pruett3 | K. A. Gifford4 | J. E. Locke5 | A. M. Cameron6 | M. J. Englesbe7 | C. S. Kuhr8 | J. F. Magliocca9 | K. R. McCune10 | K. L. Mekeel11 | S. J. Pelletier12 | A. L. Singer13 | D. L. Segev6 1Department of Surgery, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX, USA 2Liver Transplantation Program, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, USA 3Division of Transplantation, Department of Surgery, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA 4American Society of Transplant Surgeons, Arlington, VA, USA 5University of Alabama at Birmingham Comprehensive Transplant Institute, Birmingham, AL, USA 6Department of Surgery, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA 7Department of Surgery, Section of Transplantation, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA 8Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle, WA, USA 9Department of Surgery, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, USA 10Department of Surgery, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA 11Division of Transplantation and Hepatobiliary Surgery, University of California San Diego, San Diego, CA, USA 12Division of Transplant Surgery, Department of Surgery, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA 13Transplant Center, Mayo Clinic, Phoenix, AZ, USA Correspondence Dorry L. Segev The American Society of Transplant Surgeons (ASTS) PROviding better Access To Email: [email protected] Organs (PROACTOR) Task Force was created to inform ongoing ASTS organ access efforts. Task force members were charged with comprehensively cataloguing current organ access activities and organizing them according to stakeholder type. -

The Legacy of Tom Starzl Is Alive and Well in Transplantation Today1

The Legacy of Tom Starzl Is Alive and Well in Transplantation Today1 JAMES F. MARKMANN Chief, Division of Transplant Surgery Co-Director, Center for Transplantation Sciences Department of Surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital Claude E. Welch Professor, Harvard Medical School Introduction It is an honor to celebrate the life and career of Dr. Thomas Starzl with the American Philosophical Society. As Dr. Clyde Barker so elegantly summarized in his talk, “Tom Starzl and the Evolution of Transplanta- tion,”2 Dr. Starzl was a larger-than-life figure whose allure drew young surgeons to the field of liver transplantation and spurred them to careers as surgeon-scientists. Dr. Starzl’s impact still lives on today through those he inspired and by the influence of his body of work. To illustrate the enduring nature of his scientific contributions, I will review three areas of active transplant research that have the potential to radically advance the field, which connect with foundational work by Dr. Starzl. The compendium of Dr. Starzl’s work, with over 2,200 scientific papers, 300 books and chapters, 1,300 presentations, and hundreds of trainees, far exceeds even the most prolific efforts of other contributors to transplantation; corroborating his preeminence in the field, in 1999 he was identified as the most cited scientist in all of clin- ical medicine.3 It was a relatively simple task to find robust threads of his early investigations in the advances of today because his work permeates nearly every aspect of the field. The areas of work on which I will focus seek to address the two primary challenges facing the field of transplantation—the need for toxic lifelong immunosuppression to prevent allograft rejection, and an inadequate organ supply to treat all those who would benefit from organ replacement. -

Of Organ Transplants

2 • Weekender, April 27, 2019, Reid Newspapers Family and friends walk Oklahoma City Memorial Marathon to honor Perry teen Two families bonded together by sports with determination, passion donor. We wanted something good to earlier he wouldn’t make it the heart of a teenage baseball player and focus — and inspired his fellow come of our son’s death, and helping through the night. carry on Brendon McLarty’s legacy teammates to play the best they to save other’s lives was just that,” “We are so very appreciative by embracing what he cared about. could. Brendon’s mom, Lori McLarty said. his heart went to such an amazing Friends and family of the teen will “He was very selfless in a way Oklahoma is a first person man, and so happy to have had the walk in the Oklahoma City Memorial that’s hard to articulate,” Jennifer authorization state, which is an opportunity to meet Kerry and hear Marathon this year, not only Blair, Brendon’s aunt said. “He individual’s legally binding decision Brendon’s heart beat again,” Lori remembering the lives lost in the appreciated the small things in life. to become an organ and tissue donor said. 1995 bombing, but also to celebrate He lived life and touched so many after his or her death. The decision The Creach and McLarty families the life of a young organ donor who people’s lives in 16 years, and was to become an organ donor by an have been in touch for the past passed away in 2012. -

Living with Liver Transplantation Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Main Entry Under Title: Living with Liver Transplantation Includes Index

Living with Liver Transplantation Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Main entry under title: Living with liver transplantation Includes index. 1. Liver--Transplantation 2. Liver--Transplantation--Patients--Care. I. British Columbia Transplant Society. RD546.L48 1995 617.5’560592 C95-911011-9 Copyright © British Columbia Transplant Society, 1996 No part of this manual may be reproduced without the written permission of the Director (or designate) of the British Columbia Transplant Society. 2 Living with Liver Transplantation Acknowledgments I would like to thank all of the health care professionals of the various transplant teams who participated in the development of this manual. Their time, patience, and guidance was appreciated. I would like to extend a very special thank you to the manual committee members from the Vancouver Hospital and Health Sciences Centre, St. Paul’s Hospital, and BC Transplant Society for their involvement in the monumental task of writing multi-organ manuals. Without their commitment of time, sharing of expertise, and genuine concern for providing the best possible patient education material, this manual would not be possible. I would also like to thank the Kidney Foundation of Canada for permission to use some of the graphics in this manual. Yours Sincerely, Sue Howard Clinical Coordinator British Columbia Transplant Society Manual Committee Chairperson Living with Liver Transplantation 3 Table of Contents Introduction Chapter 1: Transplantation History of Transplantation ............................................................7-8