A Framework and Guidelines for Moving Toward Sustainable Water Resources Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ensuring Availability and Sustainable Management Of

Issue brief SDG 6 © Dan-Roizer ENSURING AVAILABILITY AND SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF WATER AND SANITATION FOR ALL Sustainable Development Goal 6 (SDG 6) – Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all – confirms the importance of water and sanitation in the global political agenda. Building on the relevant Millennium Development Goal, SDG 6 addresses the sustainability of access to water and sanitation by focusing on the quality, availability and management of freshwater resources. The individual targets of SDG 6 Environmental dimension of UN Environment and SDG 6 cover the entire water cycle and its SDG 6 interconnections: As the global environmental authority, the SDG 6 recognizes that countries’ social United Nations Environment Programme ➡ 6.1: provision of drinking water development and economic prosperity (UN Environment) connects the issue of depend on the sustainable management of freshwater to other aspects of sustainable ➡ 6.2: sanitation and hygiene freshwater resources and ecosystems. development, such as oceans, land and services SDG 6 acknowledges that ecosystems and agriculture. This work entails building their inhabitants, including humans, are national capacity to monitor freshwater ➡ 6.3: treatment and reuse of water users and that their activities on land ecosystem health, including water wastewater and ambient can compromise the quality and availability quality, facilitating integrated water water quality of fresh water. resources management processes and ➡ 6.4: water-use efficiency and the implementation thereof, and providing scarcity The water-related ecosystems addressed guidelines and inputs for country-level in SDG 6 include wetlands, rivers, aquifers action to protect and restore freshwater ➡ 6.5: integrated water resources and lakes, which sustain a high level of ecosystems at the national level. -

Past and Future Freshwater Use in the United States: a Technical Document Supporting the 2000 USDA Forest Service RPA Assessment

PastPast andand FutureFuture FreshwaterFreshwater UseUse inin thethe UnitedUnited StatesStates THOMAS C. BROWN UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE A Technical Document Supporting the 2000 USDA Forest Service RPA Assessment FOREST SERVICE ROCKY MOUNTAIN RESEARCH STATION GENERAL TECHNICAL REPORT RMRS-GTR-39 SEPTEMBER 1999 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE FOREST SERVICE Abstract Brown, Thomas C. 1999. Past and future freshwater use in the United States: A technical document supporting the 2000 USDA Forest Service RPA Assessment. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-39. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, 47 p. Water use in the United States to the year 2040 is estimated by extending past trends in basic water- use determinants. Those trends are largely encouraging. Over the past 35 years, withdrawals in industry and at thermoelectric plants have steadily dropped per unit of output, and over the past 15 years some irrigated regions have also increased the efficiency of their water use. Further, per-capita domestic withdrawals may have finally peaked. If these trends continue, aggregate withdrawals in the U.S. over the next 40 years will stay below 10% of the 1995 level, despite a 41% expected increase in population. However, not all areas of the U.S. are projected to fare as well. Of the 20 water resource regions in the U.S., withdrawals in seven are projected to increase by from 15% to 30% above 1995 levels. Most of the substantial increases are attributable to domestic and public or thermoelectric use, although the large increases in 3 regions are mainly due to growth in irrigated acreage. -

Ecological Sustainability Within California's Improved Forest Management Carbon Offsets Program Cory Hertog Clark University, [email protected]

Clark University Clark Digital Commons International Development, Community and Master’s Papers Environment (IDCE) 5-2018 Ecological Sustainability within California's Improved Forest Management Carbon Offsets Program Cory Hertog Clark University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.clarku.edu/idce_masters_papers Part of the Environmental Policy Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Nature and Society Relations Commons, Physical and Environmental Geography Commons, and the Policy Design, Analysis, and Evaluation Commons Recommended Citation Hertog, Cory, "Ecological Sustainability within California's Improved Forest Management Carbon Offsets Program" (2018). International Development, Community and Environment (IDCE). 195. https://commons.clarku.edu/idce_masters_papers/195 This Capstone is brought to you for free and open access by the Master’s Papers at Clark Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Development, Community and Environment (IDCE) by an authorized administrator of Clark Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Ecological Sustainability within California’s Improved Forest Management Carbon Offsets Program Cory Hertog May 2018 A Master’s Paper Submitted to the faculty of Clark University, Worcester, Massachusetts, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degrees of Master of Science of Environmental Science and Policy in the department of International Development, Community, and Environment and a Master of Business Administration in the Graduate School of Management And accepted on the recommendation of Dominik Kulakowski - Ph.D. Will O’Brien - J.D., M.B.A Graduate School of Geography Graduate School of Management Abstract Ecological Sustainability within California’s Improved Forest Management Carbon Offsets Program Cory Hertog Forest Carbon offsets are being used as a climate change mitigation strategy in multiple programs around the world. -

Sparrow-Web: a Graphical Interactive System for Displaying Reach-Level Water- Resource Information for Rivers of the Conterminous United States

SPARROW-WEB: A GRAPHICAL INTERACTIVE SYSTEM FOR DISPLAYING REACH-LEVEL WATER- RESOURCE INFORMATION FOR RIVERS OF THE CONTERMINOUS UNITED STATES Michael C. Ierardi, Richard B. Alexander, Gregory E. Schwarz, and Richard A. Smith* ABSTRACT: The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) has developed an interactive Web-based tool called SPARROW-Web, for displaying water-quality model results and associated reach-level information for more than 63,000 rivers in the conterminous United States. Access is provided through a user-navigated hierarchical system of mapped watersheds, based on the Water Resources Council hydrologic drainage basin classification for the United States. These nested drainage basin classifications include 18 water-resources regions, 204 subregions, 334 accounting units, and 2,106 hydrologic cataloging units (HUC). Interactive maps of the HUC watersheds include state and county boundaries, major cities, HUC names and HUC code numbers, and river reaches from the enhanced U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's River Reach File (1:500,000 RF1). Additional information can be accessed below the cataloging unit interactive maps that reference the ”Science in Your Watershed” Web site. This site provides access to USGS National Water Information System (NWIS) real- time streamflow stations and other water-resource information related to the selected watershed. Selection of an individual river reach on the HUC-level maps displays stream characteristics such as mean discharge and velocity, and watershed characteristics for the drainage basin above the reach, including drainage area, land-use, population, nutrient sources, and predictions of mean-annual nutrient concentrations and yields (total nitrogen and phosphorus) from the SPARROW (SPAtially Referenced Regressions On Watershed attributes) model. -

Sustainable Livelihoods and Ecosystems Management

Created in 1948, IUCN - The World Conservation Union brings together 77 states, 112 government agencies, 735 NGOs, 35 affiliates, and some 10,000 scientists and experts from 181 countries in a unique worldwide partnership. IUCN’s mission is to influence, e ncourage and assist societies throughout the world to con- serve the integrity and diversity of nature and to ensure that any use of natural resources is equitable and ecologically sustain- able. IUCN is the world's largest environmental knowledge network and has helped over 75 countries to prepare and implement national conservation and biodiversity strategies. IUCN is a multi- cultural, multilingual organization with 1000 staff located in 42 countries. Its headquarters are in Gland, Switzerland. http://www.iucn.org [email protected] Sustainable livelihoods and ecosystems management For the Preparatory Committee for the World Summit on Sustainable Development - 4 th Preparatory Meeting, Bali (Indonesia) While one cannot say with any confidence what forms an ecological crunch might take, when it might happen, or how severe it might be, it is easier to predict who will have the worst of it. The poor and powerless cannot shield themselves from ecological problems today, nor will they be able to do it in the future. J.R. McNeill, “Something New under the Sun” Introduction As a conservation organization that puts people at centre stage in its mission and vision, IUCN welcomes the new international focus on poverty alleviation. We know from our own experience that the pursuit of enviro nmental goals at the expense of economic well-being and social justice is doomed to fail. -

Green Consumerism: Moral Motivations to a Sustainable Future

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Green consumerism: moral motivations to a sustainable future 1 2 3 Sonya Sachdeva , Jennifer Jordan and Nina Mazar Green consumerism embodies a dilemma inherent in many more expensive green products that may act as a barrier to prosocial and moral actions — foregoing personal gain in favor engaging in green consumerism. Nonetheless there are of a more abstract, somewhat intangible gain to someone or several recurring themes in the expanse of literature on something else. In addition, as in the case of purchasing more the topic of green consumerism, which may shine a light expensive green products, there is sometimes a very literal cost on ways to promote green consumerism. that may act as a barrier to engaging in green consumerism. The current review examines endogenous, exogenous, and structural factors that promote green consumerism. We also What is green consumerism? 4 discuss its potential positive and negative spillover effects. We Oxymoronic implications aside, green consumerism is, close by discussing areas of research on green consumerism for a significant portion of the Western industrial popula- that are lacking — such as the moral framing of green tion, an accessible way to engage in pro-environmental, consumerism and the expansion of the cultural context in which sustainable behavior. An operational definition of green it is defined and studied. consumerism subsumes a list of behaviors that are under- Addresses taken with the intention of promoting positive environ- 1 5 U.S. Forest Service, United States mental effects. Some prototypical behaviors that fall 2 University of Groningen, The Netherlands within this rather vague definition are purchasing appli- 3 University of Toronto, Canada ances with energy star labels, buying organic products, or turning off electrical appliances when not in use, and Corresponding author: Sachdeva, Sonya ([email protected]) taking shorter showers. -

Perspectives on Climate Change and Sustainability

20 Perspectives on climate change and sustainability Coordinating Lead Authors: Gary W. Yohe (USA), Rodel D. Lasco (Philippines) Lead Authors: Qazi K. Ahmad (Bangladesh), Nigel Arnell (UK), Stewart J. Cohen (Canada), Chris Hope (UK), Anthony C. Janetos (USA), Rosa T. Perez (Philippines) Contributing Authors: Antoinette Brenkert (USA), Virginia Burkett (USA), Kristie L. Ebi (USA), Elizabeth L. Malone (USA), Bettina Menne (WHO Regional Office for Europe/Germany), Anthony Nyong (Nigeria), Ferenc L. Toth (Hungary), Gianna M. Palmer (USA) Review Editors: Robert Kates (USA), Mohamed Salih (Sudan), John Stone (Canada) This chapter should be cited as: Yohe, G.W., R.D. Lasco, Q.K. Ahmad, N.W. Arnell, S.J. Cohen, C. Hope, A.C. Janetos and R.T. Perez, 2007: Perspectives on climate change and sustainability. Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, M.L. Parry, O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden and C.E. Hanson, Eds., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 811-841. Perspectives on climate change and sustainable development Chapter 20 Table of Contents .....................................................813 Executive summary 20.7 Implications for regional, sub-regional, local and sectoral development; access ...................814 .............826 20.1 Introduction: setting the context to resources and technology; equity 20.7.1 Millennium Development Goals – 20.2 A synthesis of new knowledge relating -

A Critical Reading of Permaculture Literature

Master thesis in Sustainable Development 2018/14 Examensarbete i Hållbar utveckling The quest for sustainability – a critical reading of permaculture literature ‘ Tove Janzon DEPARTMENT OF EARTH SCIENCES INSTITUTIONEN FÖR GEOVETENSKAPER Master thesis in Sustainable Development 2018/14 Examensarbete i Hållbar utveckling The quest for sustainability – a critical reading of permaculture literature Tove Janzon Supervisor: Frans Lenglet Evaluator: Petra Hansson Copyright © Tove Janzon and the Department of Earth Sciences, Uppsala University Published at Department of Earth Sciences, Uppsala University (www.geo.uu.se), Uppsala, 2018 Content 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Background ........................................................................................................................................ 1 2.1 The sustainable development concept ........................................................................................... 1 2.1.1 History .................................................................................................................................... 1 2.1.2 Definitions .............................................................................................................................. 2 2.2 The permaculture concept ............................................................................................................. 2 2.2.1 History ................................................................................................................................... -

Inclusion of Life Cycle Thinking in a Sustainability-Oriented Consumer's

sustainability Article Inclusion of Life Cycle Thinking in a Sustainability-Oriented Consumer’s Typology: A Proposed Methodology and an Assessment Tool Anna Lewandowska 1,*, Joanna Witczak 1, Pasquale Giungato 2 ID , Christian Dierks 3, Przemyslaw Kurczewski 4 and Katarzyna Pawlak-Lemanska 1 1 Faculty of Commodity Science, Poznan University of Economics and Business, 61-875 Poznan, Poland; [email protected] (J.W.); [email protected] (K.P.-L.) 2 Chemistry Department, University of Bari Aldo Moro, Taranto district-via Alcide de Gasperi, 74123 Taranto, Italy; [email protected] 3 Fraunhofer Project Group Materials Recycling and Resource Strategies, Brentanostrasse 2a, 63755 Alzenau, Germany; [email protected] 4 Faculty of Machines and Transportation, Poznan University of Technology, Piotrowo 3, 60-965 Poznan, Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-61-854-3121 Received: 8 April 2018; Accepted: 29 May 2018; Published: 1 June 2018 Abstract: Characterizing consumers in terms of their propensity to practice sustainable consumption represents an interesting research challenge in which a crucial role is played by the questionnaire in terms of its structure and classification criteria. Various classification rules have been proposed in the literature, which can be used to identify consumer types and signify their propensity to practice the principles of sustainable development in daily life. In this paper, we based our approach in designing a classification tool on a combination of two elements: the concept of voluntary simplicity as a pillar for consumer characteristics and the idea of assessing consumers by using filters, in a modified form introducing many new aspects of life-cycle thinking. -

Sustainable Water Management and Wetland Restoration Strategies in Northern China

China Sustainable Water This book depicts the results of a research project in northern China, where an international and interdisciplinary team of researchers from Italy, Germany and China has applied a broad range of methodology in order to answer basic and Management applied research questions and derive comprehensive re- commendations for sustainable water management and wetland restoration. The project primarily focused on eco- system services, e.g. the purification of water and biomass and Wetland production. In particular, the ecosystem function and use of reed (Phragmites australis) and the perception as well as the value of water as a resource for Central Asia’s multicultural societies was analysed. Restoration Strategies in Northern China Sustainable Water Management and Wetland Restoration Strategies in Northern in Strategies Restoration Wetland and Management Water Sustainable Edited by Giuseppe Tommaso Cirella Stefan Zerbe Cirella, Zerbe (eds.) (eds.) Zerbe Cirella, 25,00 Euro www.unibz.it/universitypress Sustainable Water Management and Wetland Restoration Strategies in Northern China Edited by Giuseppe Tommaso Cirella Stefan Zerbe On behalf of Stifterverband für die Deutsche Wissenschaft Kurt-Eberhard-Bode-Stiftung für medizinische und naturwissenschaftliche Forschung Design: DOC.bz Printing: Digiprint, Bozen/Bolzano © 2014 by Bozen-Bolzano University Press Free University of Bozen-Bolzano All rights reserved 1st edition www.unibz.it/universitypress ISBN 978-88-6046-069-1 E-ISBN 978-88-6046-109-4 This work—excluding the cover and the quotations—is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Contents Introduction Stefan Zerbe, Giuseppe Tommaso Cirella, Niels Thevs ............................................. 1 1. SuWaRest, the “Third Culture” and environmental ethics Konrad Ott ............................................................................................................ -

Dam Nation: a Geographic Census of American Dams and Their Large-Scale Hydrologic Impacts William L

WATER RESOURCES RESEARCH, VOL. 35, NO. 4, PAGES 1305–1311, APRIL 1999 Dam nation: A geographic census of American dams and their large-scale hydrologic impacts William L. Graf Department of Geography, Arizona State University, Tempe Abstract. Newly available data indicate that dams fragment the fluvial system of the continental United States and that their impact on river discharge is several times greater than impacts deemed likely as a result of global climate change. The 75,000 dams in the continental United States are capable of storing a volume of water almost equaling one year’s mean runoff, but there is considerable geographic variation in potential surface water impacts. In some western mountain and plains regions, dams can store more than 3 year’s runoff, while in the Northeast and Northwest, storage is as little as 25% of the annual runoff. Dams partition watersheds; the drainage area per dam varies from 44 km2 (17 miles2) per dam in New England to 811 km2 (313 miles2) per dam in the Lower Colorado basin. Storage volumes, indicators of general hydrologic effects of dams, range 2 2 2 from 26,200 m3 km 2 (55 acre-feet mile 2) in the Great Basin to 345,000 m3 km 2 (725 2 acre-feet mile 2) in the South Atlantic region. The greatest river flow impacts occur in the Great Plains, Rocky Mountains, and the arid Southwest, where storage is up to 3.8 times the mean annual runoff. The nation’s dams store 5000 m3 (4 acre-feet) of water per person. Water resource regions have experienced individualized histories of cumulative increases in reservoir storage (and thus of downstream hydrologic and ecologic impacts), but the most rapid increases in storage occurred between the late 1950s and the late 1970s. -

Synergies Between Adaptation and Mitigation

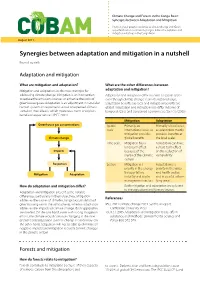

Climate Change and Forests in the Congo Basin: Synergies between Adaptation and Mitigation Analysing local people’s resilience to climate change and REDD+ opportunities to recommend synergies between adaptation and mitigation initiatives in the Congo Basin August 2011 Synergies between adaptation and mitigation in a nutshell Bruno Locatelli Adaptation and mitigation What are mitigation and adaptation? What are the other differences between Mitigation and adaptation are the two strategies for adaptation and mitigation? addressing climate change. Mitigation is an intervention Adaptation and mitigation differ in terms of spatial scales: to reduce the emissions sources or enhance the sinks of even though climate change is an international issue, greenhouse gases. Adaptation is an ‘adjustment in natural or adaptation benefits are local and mitigation benefits are human systems in response to actual or expected climatic global. Adaptation and mitigation also differ in terms of stimuli or their effects, which moderates harm or exploits temporal scales and concerned economic sectors (Tol 2005). beneficial opportunities’ (IPCC 2001). Mitigation Adaptation Greenhouse gas concentrations Spatial Primarily an Primarily a local issue, scale international issue, as as adaptation mostly mitigation provides provides benefits at Climate change global benefits the local scale Time scale Mitigation has a Adaptation can have long-term effect a short-term effect Impacts because of the on the reduction of inertia of the climatic vulnerability system Responses Sectors Mitigation is a Adaptation is a priority in the energy, priority in the water transportation, and health sectors Mitigation Adaptation industry and waste and in coastal or low- management sectors lying areas How do adaptation and mitigation differ? Both mitigation and adaptation are relevant to the agriculture and forestry sectors Adaptation and mitigation present some notable differences, particularly in their objectives.