Exhibition Guide EN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sam Elliott “I Think Anytime You Can Affect People in General, in a Positive Way, Then You’Re a Lucky Individual.” —Sam Elliott

Julia Louis-Dreyfus Contributing Writers: Howard Erman Les Goldberg Ronnie Greenberg Dr. Robert Horseman Judith Rogow Debbie L. Sklar VOLUME 45, NUMBER 8 Nick Thomas AUGUST 2019 “Serving The Needs of Orange County & Long Beach Seniors Since 1974” Sam Elliott “I think anytime you can affect people in general, in a positive way, then you’re a lucky individual.” —Sam Elliott What’s Inside.... Calendar of Events ....................................5 Classifieds .............................................6-7 Sam Elliott..............................................10 Gadget Geezer ........................................12 Fabulous Finds ........................................14 Book Club ...............................................21 Magic of Cambria .....................................22 Busy Boomers .........................................31 In The Spotlight ......................................35 Tinseltown Talks ......................................41 Orange County • Long Beach Page 2 SENIOR REPORTER [email protected] AUGUST 2019 Advertise in The Senior Reporter’s CLASSIFIED & $2,945 PROFESSIONAL $2,745 SERVICE $3,185 DIRECTORY $2,745 $575 Only $37.50/ mo with a 6-mo. commitment seniorreporter [email protected] or call Bill Thomas at (714) 458-5703 Page 3 SENIOR REPORTER [email protected] AUGUST 2019 New Cars By Jim McDevitt While my new car is un- and down while keeping dergoing repairs, I have a my foot on the brake pedal See the world’s only authentic flying new 2019 loaner car. Ev- until a very small red light Japanese Zero fighter I still have monthly pay- ery time I start this car appears on the dashboard ments I am making on the up the radio goes on with that says park. someone yelling words to Planes of Fame 2016 car I bought new. I Air Museum have it over 3 years now hip hop music. -

David Wojnarowicz and the Surge of Nuances. Modifying Aesthetic Judgment with the Influx of Knowledge

David Wojnarowicz and the Surge of Nuances. Modifying Aesthetic Judgment with the Influx of Knowledge Author Affiliation Paul R. Abramson & University of California, Tania L. Abramson Los Angeles Abstract: Learning that an artist was a victim of inconceivable torment is critical to how their artworks are experienced. Forced as it were to absorb the wretched demons from the here and now, artists such as David Wojnarowicz have implau- sibly found the resolve to depict this adversity, and its psychological detritus, in their singularly creative manners. Recognised for his autobiographical writings no less than his artwork, Wojnarowicz is especially admired for his sheer defiance of conventional life scripts, and his fortitude in the face of adversity in the circum- scribed world of imaginative constructions. Arthur Rimbaud in New York, A Fire in My Belly, and Wind (for Peter Hujar) for example. The enduring value of his artwork, inextricably enhanced by his diaries and essays, is that they simultane- ously provide a narrative portal into the untangling of his inner life, as well as fundamentally influence how these works are perceived. When looking at two paintings, ostensibly by Rembrandt, is there an aesthetic difference in how these paintings are experienced if we know that one of the two paintings is a forgery? Most certainly, declared Nelson Goodman, who noted that this bit of knowledge ‘makes the consequent demands that modify and differentiate my present experience in looking at the two [Rembrandt] paintings’.1 Is that also true about depictions of Christ on the cross? Does knowledge of Christ’s story alter how Michelangelo’s Christ on the Cross is experienced? If what we know, or think we know, has the capacity to ultimately influence © Aesthetic Investigations Vol 3, No 1 (2020), 146-157 Paul R. -

Community Connection Third Annual Poetry & Prose 2013

DECEMBER 2013 ILLINOIS TENTH CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT DEMOCRATS NEWSLETTER: SLAM EDITION COMMUNITY CONNECTION THIRD ANNUAL POETRY & PROSE 2013 LITERARY EDITION OUR 2013 POETRY + PROSE SLAM WINNERS First Prize, Poetry First Prize, Prose Topiltzin Gomez, Waukegan High School, Ulises Acosta, Cristo Rey St. Martin College Prep, “Red Eye Lullaby ” “The Man in the Dark Corner” Second Prize, Poetry Second Prize, Prose Nathali Ibarra, Waukegan High School, Jennifer Cornejo, Cristo Rey St. Martin College Prep, “Above My Head” “Something Lovely Wicked and True” Third Prize, Poetry Third Prize, Prose Alejandro Martinez, Waukegan High School, Josue Pasillas, Waukegan High School, “We Both Reached for the Gun” “A Sunny Summer Day” Honorable Mention, Poetry Honorable Mention, Prose Manuel Gutierrez, Cristo Rey St. Martin College Gilberto Colin, Waukegan High School, Prep, “From Where?” “Fitting In” Honorable Mention, Poetry Honorable Mention, Prose Michelle Hinojosa, Cristo Rey St. Martin College Abrianna Matus, Cristo Rey St. Martin College Prep, Prep, “Dreamers Dilemma” “That Old Nightmare” Honorable Mention, Poetry Honorable Mention, Prose Jenny Nolasco, Cristo Rey St. Martin College Prep, “Dream Catcher” Bianca Uribe, Cristo Rey St. Martin College Prep, “Untitled” Honorable Mention, Poetry Sahely Rivera, Cristo Rey St. Martin College Prep, “Ocean of Dreamers” Slam participants pose with Judge Judy Tepfer 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Winners .............................................................. 2 A View from the Audience, Part 1 ......................................... -

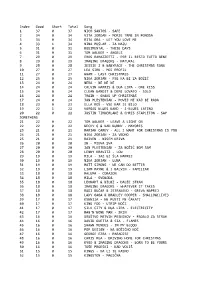

Index Good Short Total Song 1 37 0 37 NICO SANTOS

Index Good Short Total Song 1 37 0 37 NICO SANTOS - SAFE 2 34 0 34 VITA JORDAN - MORJE TRME IN PONOSA 3 34 0 34 RITA ORA - LET YOU LOVE ME 4 33 1 34 NINA PUŠLAR - ZA NAJU 5 31 0 31 RUDIMENTAL - THESE DAYS 6 31 0 31 TOM WALKER - ANGELS 7 29 0 29 EROS RAMAZZOTTI - PER IL RESTO TUTTO BENE 8 29 0 29 IMAGINE DRAGONS - NATURAL 9 28 0 28 JESSIE J & BABYFACE - THE CHRISTMAS SONG 10 27 0 27 LEA SIRK - MOJ PROFIL 11 27 0 27 WHAM - LAST CHRISTMASS 12 25 0 25 NIKA ZORJAN - FSE KA BI ZA BOŽIČ 13 24 0 24 NERA - NE NE NE 14 24 0 24 CALVIN HARRIS & DUA LIPA - ONE KISS 15 24 0 24 CLEAN BANDIT & DEMI LOVATO - SOLO 16 24 0 24 TRAIN - SHAKE UP CHRISTMAS 17 24 0 24 JAN PLESTENJAK - POVEJ MI KAJ BI RADA 18 23 0 23 ELLA ROŠ - VSE KAR JE BILO 19 22 1 23 VARGAS BLUES BAND - 1-BLUES LATINO 20 22 0 22 JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE & CHRIS STAPLETON - SAY SOMETHING 21 22 0 22 TOM WALKER - LEAVE A LIGHT ON 22 22 0 22 BECKY G & BAD BUNNY - MAYORES 23 21 0 21 MARIAH CAREY - ALL I WANT FOR CHRISTMAS IS YOU 24 21 0 21 NIKA ZORJAN - ZA VEDNO 25 21 0 21 RAIVEN - NISEM KRIVA 26 20 0 20 2B - MIDVA SVA 27 20 0 20 JAN PLESTENJAK - ZA BOŽIČ BOM SAM 28 20 0 20 LENNY KRAVITZ - LOW 29 19 0 19 MILA - JAZ BI ŠLA NAPREJ 30 19 0 19 NIKA ZORJAN - LUNA 31 19 0 19 MATT SIMONS - WE CAN DO BETTER 32 19 0 19 LIAM PAYNE & J BALVIN - FAMILIAR 33 18 0 18 MALUMA - CORAZON 34 18 0 18 MILA - SVOBODA 35 18 0 18 LEONART & BILBI - DALEČ STRAN 36 18 0 18 IMAGINE DRAGONS - WHATEVER IT TAKES 37 18 0 18 RUDI BUČAR & ISTRABEND - GREVA NAPREJ 38 18 0 18 LADY GAGA & BRADLEY COOPER - SHALLOW(LIVE) 39 17 0 17 KSENIJA -

Pdf Liste Totale Des Chansons

40ú Comórtas Amhrán Eoraifíse 1995 Finale - Le samedi 13 mai 1995 à Dublin - Présenté par : Mary Kennedy Sama (Seule) 1 - Pologne par Justyna Steczkowska 15 points / 18e Auteur : Wojciech Waglewski / Compositeurs : Mateusz Pospiezalski, Wojciech Waglewski Dreamin' (Révant) 2 - Irlande par Eddie Friel 44 points / 14e Auteurs/Compositeurs : Richard Abott, Barry Woods Verliebt in dich (Amoureux de toi) 3 - Allemagne par Stone Und Stone 1 point / 23e Auteur/Compositeur : Cheyenne Stone Dvadeset i prvi vijek (Vingt-et-unième siècle) 4 - Bosnie-Herzégovine par Tavorin Popovic 14 points / 19e Auteurs/Compositeurs : Zlatan Fazlić, Sinan Alimanović Nocturne 5 - Norvège par Secret Garden 148 points / 1er Auteur : Petter Skavlan / Compositeur : Rolf Løvland Колыбельная для вулкана - Kolybelnaya dlya vulkana - (Berceuse pour un volcan) 6 - Russie par Philipp Kirkorov 17 points / 17e Auteur : Igor Bershadsky / Compositeur : Ilya Reznyk Núna (Maintenant) 7 - Islande par Bo Halldarsson 31 points / 15e Auteur : Jón Örn Marinósson / Compositeurs : Ed Welch, Björgvin Halldarsson Die welt dreht sich verkehrt (Le monde tourne sens dessus dessous) 8 - Autriche par Stella Jones 67 points / 13e Auteur/Compositeur : Micha Krausz Vuelve conmigo (Reviens vers moi) 9 - Espagne par Anabel Conde 119 points / 2e Auteur/Compositeur : José Maria Purón Sev ! (Aime !) 10 - Turquie par Arzu Ece 21 points / 16e Auteur : Zenep Talu Kursuncu / Compositeur : Melih Kibar Nostalgija (Nostalgie) 11 - Croatie par Magazin & Lidija Horvat 91 points / 6e Auteur : Vjekoslava Huljić -

David Wojnarowicz. History Keeps Me Awake at Night

David Wojnarowicz. History Keeps Me Awake at Night DATES: 29 May – 30 September, 2019 PLACE: Sabatini Building, Floor 1 ORGANIZATION: Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, in collaboration with the Museo Reina Sofia, Madrid, and the Mudam Luxembourg – Musée d’Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean, Luxembourg CURATORSHIP: David Breslin and David Kiehl COORDINATION: Rafael García TOUR: Whitney Museum of American Art, Nueva York: 13 July– 30 September, 2018 Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid: 29 May – September 30, 2019 Mudam Luxembourg - Musée d’Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean, Luxemburg: 26 October, 2019 – 2 February 2020 The exhibition David Wojnarowicz. History Keeps Me Awake at Night is the first major review of the multifaceted creative work of the artist, writer and activist David Wojnarowicz (New Jersey, 1954-New York, 1992) since the 1999 exhibition at the New Museum in New York and the 2012 publication of Fire in the Belly: The Life and Times of David Wojnarowicz, his Cynthia Carr's detailed biography. This major retrospective, organized by the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York in collaboration with the Reina Sofia Museum and the Mudam Luxembourg - Musée d'Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean, not only examines the plurality of styles and media that the artist displayed in his practice, but also relates his work to the political, social and artistic context of New York in the 1980s and early 1990s. That was a time marked by economic uncertainty and the terrible AIDS epidemic, but also by creative energy and a series of profound cultural changes: the intersection of different movements - graffiti, new wave and no wave music, conceptual photography, performance and neo-expressionist painting - turned the American city into an artistic laboratory for innovation. -

DAVID WOJNAROWICZ (1954–1992) B

DAVID WOJNAROWICZ (1954–1992) b. 1954, Red Bank, NJ d. 1992, New York, NY SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2020 I is Someone Else, Morán Morán, Los Angeles CA David Wojnarowicz, Photography & Film, Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, Vancouver, BC 2019 History Keeps Me Awake at Night, Museum Reina Sofia, Madrid David Wojnarowicz, Photography & Film, Kunst-Werke Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin 2018 History Keeps Me Awake at Night, The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY Soon All This Will be Picturesque Ruins: The Installations of David Wojnarowicz, P·P·O·W, New York, NY David Wojnarowicz: Video and Photography, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, Germany. David Wojnarowicz: Flesh of My Flesh, Iceberg Projects, Chicago, IL 2016 Raging Through: The Art of David Wojnarowicz, Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ 2011 Spirituality, P·P·O·W, New York, NY 2009 David Wojnarowicz, Supportico Lopez, Berlin, Germany 2006 Rimbaud in New York, CABINET, London, England David Wojnarowicz, Between Bridges, London, England 2004 Out of Silence: Artworks with Original Text by David Wojnarowicz, P·P·O·W, New York, NY David Wojnarowicz: Rimbaud in New York, Roth Horowitz Gallery, New York, NY Close Up sur David Wojnarowicz, Forum des Halles Espace Rencontres, Paris, France 2001 Featured Works VI: David Wojnarowicz: The Elements, Fire and Water, Earth and Wind, Krannert Art Museum, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, IL 1999 Fever: The Art of David Wojnarowicz, New Museum, New York, NY David Wojnarowicz: The Boys Go Off -

November 2018

Date time: Number: Title: Artist: Publisher Lang: 01.11.2018 00:02:30 HD 010041 ONE FOR YOU, ONE FOR ME LA BIONDA ARCADE 00:03:06 ANG 01.11.2018 00:05:27 HD 004486 OTKAD SI OTIŠLA VLADO KALEMBER HIPERSOUND00:03:46 CRO 01.11.2018 00:09:12 HD 006575 KRALJICA POROČNEGA POTOVANJA (REMIX)CALIFORNIA MENART 00:04:18 SLO 01.11.2018 00:13:45 HD 002714 BACKSEAT OF YOUR CADILLAC CC CATCH BMG 00:03:19 ANG 01.11.2018 00:17:00 HD 018164 NE ZNAM PLESAT GIBONNI DALLAS 00:03:49 CRO 01.11.2018 00:20:49 HD 037931 POD MOJO KOŽO REBEKA DREMELJ 00:03:37 SLO 01.11.2018 00:24:49 HD 028309 LOVE CHANGES EVERYTHING MUSIKK FEAT. JOHN ROCK ORPHEUS MUSIC00:03:47 ANG 01.11.2018 00:28:35 HD 003499 1 MILJO OD OBALE CALIFORNIA MENART 00:03:13 SLO 01.11.2018 00:31:46 HD 020857 DELAM JANI KOVAČIČ RTS 00:03:16 SLO 01.11.2018 00:35:09 HD 002272 TO THE MOON AND BACK SAVAGE GARDEN COLUMBIA 00:05:36 ANG 01.11.2018 00:40:35 HD 002049 OLD POP IN AN OAK REDNEX ZOMBA RECORDS00:03:31 ANG 01.11.2018 00:44:05 HD 002456 DAJ MI EN DIM SLAVKO IVANČIČ NIKA 00:03:53 SLO 01.11.2018 00:48:05 HD 024889 I NEED MORE OF YOU (ALMIGHTY RADIOTHE MIX) BELLAMY BROTHERS 00:03:55 ANG 01.11.2018 00:51:54 HD 048445 HČI VAŠKEGA UČITELJA MI 2 00:03:44 SLO 01.11.2018 00:55:32 HD 005718 VROČA LINIJA BABILON 00:03:44 SLO 01.11.2018 00:59:27 HD 019212 KISS THE ART OF NOISE FEAT. -

Največkrat Predvajane Skladbe V Letu 2020 Na Radiu 94

Največkrat predvajane skladbe v letu 2020 na Radiu 94 Mesto Predv. Izvajalec in skladba 1 311 REGARD - RIDE IT 2 259 MAROON 5 - MEMORIES 3 240 ONE REPUBLIC - BETTER DAYS 4 239 TONES AND I - DANCE MONKEY 5 232 ZMELKOOW & JANEZ DOWČ - KAJ NAM FALI(2020) 6 227 TABU - NA KONICAH PRSTOV 7 215 MEDUZA & BECKY HILL & GOODBOYS - LOSE CONTROL 8 212 BILLIE EILISH - BAD GUY 9 205 SAM SMITH & NORMANI - DANCING WITH A STRANGER 10 204 ROLLING STONES - LIVING IN A GHOST TOWN 11 201 LEA SIRK - V DVOJE 12 199 THEORY OF A DEADMAN - SAY NOTHING 13 196 KYGO & WHITNEY HOUSTON - HIGHER LOVE 14 194 LEWIS CAPALDI - BRUISES 15 193 HARRY STYLES - ADORE YOU 16 193 FED HORSES - ZAHODNO DEKLE 17 188 LEVANTE - SIRENE 18 188 TOM WALKER - JUST YOU AND I 19 188 LEA SIRK - PO SVOJE 20 187 BISERI - ZA NJO 21 185 LENNON STELLA & CHARLIE PUTH - SUMMER FEELINGS 22 185 VITAVOX - RAVNO OBRATNO 23 182 NINA PUŠLAR - VČERAJ IN ZA ZMERAJ 24 181 TINKARA KOVAČ - BODI Z MANO DO KONCA 25 181 MARY ROSE - KO TAKO OBJAME 26 177 SOPRANOS - NIMAM SKRBI 27 173 ŠANK ROCK - DVIGNI POGLED 28 168 AVICII & ALOE BLAC - SOS 29 167 GROMEE - LIGHT ME UP 30 165 TOPIC feat. & A7S - BREAKING ME 31 165 MATIC MARENTIČ & V. DIMENZIJA - IZBRIŠI ME S SEZNAMA 32 163 EME & ZEEBA - SAY GOODBYE 33 162 LADY GAGA - STUPID LOVE 34 159 JAN PLESTENJAK - ČLOVEK BREZ IMENA 35 155 VITAVOX - TRIK 36 154 I.C.E. - LAHKO BI BILO LEPO 37 154 AVA MAX - SO AM I 38 151 ROBIN SCHULZ & WES - ALANE 39 150 SCORPIONS - SING OF HOPE 40 148 LOST FREQUENCIES & ZONDERLING - CRAZY 41 147 WEEKND - BLINDING LIGHTS 42 146 JONAS BROTHERS -

THE GARY MOORE DISCOGRAPHY (The GM Bible)

THE GARY MOORE DISCOGRAPHY (The GM Bible) THE COMPLETE RECORDING SESSIONS 1969 - 1994 Compiled by DDGMS 1995 1 IDEX ABOUT GARY MOORE’s CAREER Page 4 ABOUT THE BOOK Page 8 THE GARY MOORE BAND INDEX Page 10 GARY MOORE IN THE CHARTS Page 20 THE COMPLETE RECORDING SESSIONS - THE BEGINNING Page 23 1969 Page 27 1970 Page 29 1971 Page 33 1973 Page 35 1974 Page 37 1975 Page 41 1976 Page 43 1977 Page 45 1978 Page 49 1979 Page 60 1980 Page 70 1981 Page 74 1982 Page 79 1983 Page 85 1984 Page 97 1985 Page 107 1986 Page 118 1987 Page 125 1988 Page 138 1989 Page 141 1990 Page 152 1991 Page 168 1992 Page 172 1993 Page 182 1994 Page 185 1995 Page 189 THE RECORDS Page 192 1969 Page 193 1970 Page 194 1971 Page 196 1973 Page 197 1974 Page 198 1975 Page 199 1976 Page 200 1977 Page 201 1978 Page 202 1979 Page 205 1980 Page 209 1981 Page 211 1982 Page 214 1983 Page 216 1984 Page 221 1985 Page 226 2 1986 Page 231 1987 Page 234 1988 Page 242 1989 Page 245 1990 Page 250 1991 Page 257 1992 Page 261 1993 Page 272 1994 Page 278 1995 Page 284 INDEX OF SONGS Page 287 INDEX OF TOUR DATES Page 336 INDEX OF MUSICIANS Page 357 INDEX TO DISCOGRAPHY – Record “types” in alfabethically order Page 370 3 ABOUT GARY MOORE’s CAREER Full name: Robert William Gary Moore. Born: April 4, 1952 in Belfast, Northern Ireland and sadly died Feb. -

Blunting the Knives: Disruption and Disintegration in the Life and Art of David Wojnarowicz

Broad Street Humanities Review, III Blunting the Knives: Disruption and Disintegration in the Life and Art of David Wojnarowicz Helena Aeberli Jesus College, Oxford 13th September 2020 1 Broad Street Humanities Review, III Blunting the Knives For David Wojnarowicz Perception’s broken mirror an umbrella of blacked out text against a newsprint of rain. New York at midnight. Windows gash mercury neon across broken boards the colour of premonitory ash. Your body moves under the shapeless garment of the moon. This darkroom mask — half-developed a luminary of silent touch, the dark-side stigma. Bodies find self-shaped craters. Your temple the shaved edge of a spoon the sirens of your skin wail. Manhattan washed with manmade moonlight. Sometimes you leave the city. Sometimes the city leaves you. In the photos your ears and forehead remain a boy’s the double exposure of chemical paint pooled on water. These things which brushes and touches and silver print cannot conceal. The hidden collarbone of moon. 2 Broad Street Humanities Review, III You stencil your own face into others; so this is posterity, the polyphonic self. 3 Broad Street Humanities Review, III Commentary In 1987 the multidisciplinary artist, writer, and activist David Wojnarowicz stands beside the bed of a dying man. The man is Peter Hujar, a photographer and Wojnarowicz’s closest friend, a onetime lover he describes as ‘my brother my father my emotional link to the world.’1 Finally, after ten months of battling against the disease which has slowly reduced his body to little more than cancer and bones, Hujar slips away. -

The Role of Programming in Interpreting LGBTQ Identities in Contemporary Art Museums

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses 4-2019 The Role of Programming in Interpreting LGBTQ Identities in Contemporary Art Museums Anna Vernacchio [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Vernacchio, Anna, "The Role of Programming in Interpreting LGBTQ Identities in Contemporary Art Museums" (2019). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ROCHESTER INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS THE ROLE OF PROGRAMMING IN INTERPRETING LGBTQ IDENTITIES IN CONTEMPORARY ART MUSEUMS A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE BACHELOR OF SCIENCE DEGREE IN MUSEUM STUDIES DEPARMENTS OF PERFORMING ARTS AND VISUAL CULTURE AND HISTORY BY ANNA VERNACCHIO APRIL 2019 Acknowledgements A huge thanks to Dr. Rebecca DeRoo for her continued encouragement, guidance, support, and positive criticism. To Dr. Petrina Foti, for her guidance in developing this topic and Smithsonian expertise. To my mom, dad, and older brother, Vincent, for all of their love and support. To my uncle and godfather, Dale Anderson, for the love, advice, and encouragement given before it could be fully appreciated. And finally to all of my colleagues in the Museum Studies department at RIT, I could not have gotten through all of this without your support, critique, and the countless jokes. The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Anna Vernacchio submitted on April 25, 2019.