Journal of Mormon History Vol. 8, 1981

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Chapter (PDF)

CONTENTS Introduction by Fawn Μ. Brodie Note on the Text ROUTE FROM LIVERPOOL το GREAT SALT LAKE VALLEY Preface [Chapters I-IX by Linforth] Chapter I. Commencement of the Latter-day Saints' Emigration—History until the Suspension in 1846 Chapter II. Memorial to the Queen—Re-opening of the Emigration—History until 1851 Chapter III. History of the Perpetual Emigrating Fund—Act of Incorporation by the General Assembly of Deseret Chapter IV. History of the Emigration from 1851 to 1852—Contemplated Routes via the Isthmus of Panama and Cape Horn Chapter V. History of the Emigration from 1852 to April, 1854—Extensive Operations of the Perpetual Emigrating Fund Company vi CONTENTS Chapter VI. Foreign Emigration passing through Liverpool 38 Chapter VII. Statistics of the Latter-day Saints' Emigration from the British Isles 40 Chapter VIII. Mode of conducting the Emigration 49 Chapter IX. Instructions to Emigrants 54 [Chapters X-XXI by Piercy] Chapter X. Departure from Liverpool—San Domingo—Cuba—The Gulf of Mexico—The Mississippi River—The Balize—Arrival at New Orleans—Attempts of "Sharpers" to board the Ship and pilfer from the Emigrants 62 Chapter XI. Louisiana—The City of New Orleans—Disembarkation 71 Chapter XII. Departure from New Orleans—Steam-Boats—Negro-Slavery— Carrollton—The Face of the Country—-Baton Rouge—Red River —Mississippi—Unwholesomeness of the waters of the Mississippi —Danger in procuring Water from the Stream—Washing away of the Banks of the River—Snags—Landing at Natchez at night —Beautiful effect caused by reflection on the Water of the Light from the Steamboat Windows—^American Taverns and Hospi- tality—Rapidity at Meals—American Cooking Stoves and Wash- ing Boards—Old Fort Rosalie—An Amateur Artist 73 Chapter XIII. -

Joseph Smith Ill's 1844 Blessing Ana the Mormons of Utah

Q). MicAael' J2umw Joseph Smith Ill's 1844 Blessing Ana The Mormons of Utah JVlembers of the Mormon Church headquartered in Salt Lake City may have reacted anywhere along the spectrum from sublime indifference to temporary discomfiture to cold terror at the recently discovered blessing by Joseph Smith, Jr., to young Joseph on 17 January 1844, to "be my successor to the Presidency of the High Priesthood: a Seer, and a Revelator, and a Prophet, unto the Church; which appointment belongeth to him by blessing, and also by right."1 The Mormon Church follows a line of succession from Joseph Smith, Jr., completely different from that provided in this document. To understand the significance of the 1844 document in relation to the LDS Church and Mormon claims of presidential succession from Joseph Smith, Jr., one must recognize the authenticity and provenance of the document itself, the statements and actions by Joseph Smith about succession before 1844, the succession de- velopments at Nauvoo after January 1844, and the nature of apostolic succes- sion begun by Brigham Young and continued in the LDS Church today. All internal evidences concerning the manuscript blessing of Joseph Smith III, dated 17 January 1844, give conclusive support to its authenticity. Anyone at all familiar with the thousands of official manuscript documents of early Mormonism will immediately recognize that the document is written on paper contemporary with the 1840s, that the text of the blessing is in the extraordinar- ily distinctive handwriting of Joseph Smith's personal clerk, Thomas Bullock, that the words on the back of the document ("Joseph Smith 3 blessing") bear striking similarity to the handwriting of Joseph Smith, Jr., and that the docu- ment was folded and labeled in precisely the manner all one-page documents were filed by the church historian's office in the 1844 period. -

The Secret Mormon Meetings of 1922

University of Nevada, Reno THE SECRET MORMON MEETINGS OF 1922 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History By Shannon Caldwell Montez C. Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D. / Thesis Advisor December 2019 Copyright by Shannon Caldwell Montez 2019 All Rights Reserved UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA RENO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by SHANNON CALDWELL MONTEZ entitled The Secret Mormon Meetings of 1922 be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS C. Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D., Advisor Cameron B. Strang, Ph.D., Committee Member Greta E. de Jong, Ph.D., Committee Member Erin E. Stiles, Ph.D., Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School December 2019 i Abstract B. H. Roberts presented information to the leadership of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in January of 1922 that fundamentally challenged the entire premise of their religious beliefs. New research shows that in addition to church leadership, this information was also presented during the neXt few months to a select group of highly educated Mormon men and women outside of church hierarchy. This group represented many aspects of Mormon belief, different areas of eXpertise, and varying approaches to dealing with challenging information. Their stories create a beautiful tapestry of Mormon life in the transition years from polygamy, frontier life, and resistance to statehood, assimilation, and respectability. A study of the people involved illuminates an important, overlooked, underappreciated, and eXciting period of Mormon history. -

Lorin C. Woolley Biography

"I Love to Hear Him Talk and Rehearse" The Life and Teachings of Lorin C. Woolley by Brian C. Hales Copyright 1993 Lorin C. Woolley became popular in the 1920s as a speaker among different groups of dissenters from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. His acceptance was greatest among men and women who had been excommunicated for practicing polygamy. On one occasion Joseph White Musser, who had listened to him many times, recorded: "I love to hear him talk and rehearse."(1) During his lifetime, Lorin C. Woolley shared many fascinating stories with his listeners. THE IMPORTANCE OF LORIN C. WOOLLEY Since the Manifesto, the practice of polygamy outside of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has been advocated by a number of interesting and dedicated individuals. Many have served as leaders in their respective pseudo-church organizations. These men have demonstrated sincerity, charisma and commitment to their cause. They have endured persecution from external sources including suffering prison sentences. Nevertheless, none of their contributions to the practice of post-manifesto polygamy compares with the offering presented by Lorin C. Woolley. Through his recollections he provided his followers with access to a line of priesthood authority, ostensibly allowing them to eternally seal plural marriages. The Need for Legitimate Authority To understand why proper authority is so important, we recall the Lord's instructions concerning the sealing power restored to Joseph Smith: All covenants, contracts, bonds, obligations, -

Moderating the Mormon Discourse on Modesty

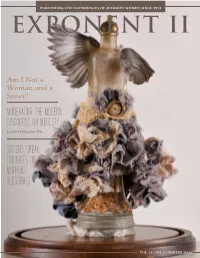

PUBLISHING THE EXPERIENCES OF MORMON WOMEN SINCE 1974 EXPONENT II Am I Not a Woman and a Sister? MODERATING THE MODERN DISCOURSE ON MODESTY Jennifer Finlayson-Fife SISTERS SPEAK: THOUGHTS ON MOTHERS’ BLESSINGS VOL. 33 | NO. 3 | WINTER 2014 04 PUBLISHING THE EXPERIENCES OF 18 Mormon Women SINCE 1974 14 16 WHAT IS EXPONENT II ? The purpose of Exponent II is to provide a forum for Mormon women to share their life 34 experiences in an atmosphere of trust and acceptance. This exchange allows us to better understand each other and shape the direction of our lives. Our common bond is our connection to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and our commitment to 24 women. We publish this paper as a living history in celebration of the strength and diversity 30 of women. 36 FEATURED STORIES ADDITIONAL FEATURES 03 LETTER FROM THE EDITOR 24 FLANNEL BOARD New Recruits in the Armies of Shelaman: Notes from a Primary Man MODERATING THE 04 AWAKENINGS Rob McFarland Making Peace with Mystery: To Prophet Jonah MORMON DISCOURSE ON MODESTY Mary B. Johnston 28 Reflections on a Wedding BY JENNIFER FINLAYSON-FIFE, WILMETTE, ILLINOIS Averyl Dietering 07 SISTERS SPEAK ON THE COVER: I believe the LDS cultural discourse around modesty is important because Sharing Experiences with Mothers’ Blessings 30 SABBATH PASTORALS Page Turner of its very real implications for women in the Church. How we construct Being Grateful for God’s Hand in a World I our sexuality deeply affects how we relate to ourselves and to one another. Moderating the Mormon Discourse on -

Essays on the Persecution of Religious Minorities by David Thomas Smith

Essays on the Persecution of Religious Minorities by David Thomas Smith A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Political Science) in the University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor William R. Clark, co-chair Professor Anna M. Grzymala-Busse, co-chair Professor Robert J. Franzese, Jr. Professor Andrei S. Markovits Professor Robert W. Mickey i Acknowledgements Throughout the last six and a half years I have benefited enormously from the mentorship and friendship of my wonderful dissertation committee members: Bill Clark, Anna Grzymala-Busse, Andy Markovits, Rob Mickey and Rob Franzese. I assembled this committee before I even knew what I wanted to write about, and I made the right choices—I cannot imagine a more supportive, patient and insightful group of advisers. They gave me badly-needed discipline when I needed it (which was all the time) and oversaw numerous episodes of Schumpeterian “creative destruction.” They also gave me more ideas than I could ever hope to assimilate, ideas which will be providing me with directions for future research for many years to come. But these huge contributions are minor in comparison to the fact that they taught me how to think like a political scientist. I couldn’t ask for anything more. All of these papers had trial runs in various internal workshops and seminars at the University of Michigan, and I profited greatly from the structured feedback that I received from the Michigan political science community, faculty and grad students alike. Thanks to everyone who was a discussant for one of these papers—Zvi Gitelman, Chuck Shipan, Sana Jaffrey, Cassie Grafstrom (twice!), Ron Inglehart, Ken Kollman, Allison Dale, Pam Brandwein, Andrea Jones-Rooy, Rob Salmond and Jenna Bednar. -

Appendix 1 Andrew Jenson, Mormon Encyclopedist Davis Bitton and Leonard J

Appendix 1 Andrew Jenson, Mormon Encyclopedist Davis Bitton and Leonard J. Arrington In November 1876, shortly after the appearance of Edward Tullidge’s zealous collector of historical records, faithful diarist, and author of Life of Brigham Young; Or, Utah and Her Founders, a twenty-six-year- more than five thousand published biographical sketches. Jenson may old Danish settler in Pleasant Grove, Utah, wrote to Daniel H. Wells, have contributed more to preserving the factual details of Latter-day a close adviser to Brigham Young. Hopeful that he would not have to Saint history than any other person; at least for sheer quantity, his spend the rest of his life as a manual laborer, the young man asked if projects will likely remain unsurpassed. Jenson’s industry, persistence, he might have permission to prepare and publish a history of Joseph and dogged determination in the face of rebuffs and disappointments Smith in the Danish language. Wells replied that he had “no hesi- have caused every subsequent Mormon historian to be indebted to him. tancy” in approving the proposal but doubted that the project, although Andreas Jensen was born in 1850 in the country village of Damgren, worthwhile, would be financially remunerative. The young immigrant in Torslev Parish, Hjørring County, Jutland, Denmark, the second son arranged his affairs at home, began the work of translating and writing, of Danish peasants.1 When Andreas was four, his parents were visited and canvassed for subscribers. by Mormon missionaries in Denmark and converted. Andreas and his Thus began the historical labors of Andrew Jenson, who for the older brother, Jens, who were subjected to harassment at school because next sixty-five years worked prodigiously in the cause of Mormon his- 1. -

WILFORD WOODRUFF's JOURNAL Kraut's PIONEER PRESS 7285

WILFORD WOODRUFF'S JOURNAL Kraut's PIONEER PRESS 7285 Highland Drive Salt Lake City, Utah 84121 Typography by ANNE WILDE PREFACE Wilford Woodruff kept one of the most important journals in the early Church. Recorded within its pages are some of the greatest moments in the Church's history, much of which might otherwise have gone unrecorded. He was personally acquainted with the Prophet Joseph Smith, Brigham Young and John Taylor, and kept a faithful record of many of their private meetings and counsel. Here for the first time in print are selected out the choicest gems of doctrine and history as they were recorded by this great man. Davis Bitton, Assistant Church Historian, wrote the following about Wilford Woodruff's journal, which covered the years from 1834 to 1898: It is one of this monumental examples of personal record-keeping. From the time he joined the Church in 1833 and through his long, eventful life, Wilford Woodruff must have spent an hour a day on it, even more when the occasion required, carefully setting down his experiences and feelings. Since he lived through exciting times and was often close to the centers of activity, his ardent consistency in writing produced one of the magnificent primary sources for the history of the Church during the nineteenth century. There are hundreds of surviving personal records from the Saints of the past century. To some extent the practice continues to the present. * * * Probably no people, with the possible exception of the Puritans or the early Quakers, have been so mindful of personal records as have the Latter-day Saints. -

Rentmeister Book Collection

Rentmeister Book Collection Contents Utah 2 Geology; Land Use ..................................................................................... 2 History ........................................................................................................ 2 Miscellaneous ............................................................................................. 7 County, Local, and Regional Utah Histories, Guidebooks, etc. ................. 8 Native Americans 17 The West 22 General ...................................................................................................... 22 Arizona ..................................................................................................... 32 California .................................................................................................. 32 Idaho ......................................................................................................... 34 Montana .................................................................................................... 34 Nevada ...................................................................................................... 35 New Mexico ............................................................................................. 35 Wyoming .................................................................................................. 35 The West (Time-Life Books Series) ........................................................ 36 Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints 39 Bibliography ............................................................................................ -

The Assigned Theme for This Lecture Is “How My Scholarship Informs

TRUTH IS REASON Robert Worrell—Department of English he assigned theme for this lecture is “How My Scholarship Informs TMy Theology.” That appears to be an invitation to bypass some of the formalities of academic writing and use the first person. The phraseology also seems to indicate that scholarship, in general, may impart information and give character to my personal theology, but it does not imply that scholarship informs theology in general. I am comfortable with that. In fact, the subjects I learn and teach in my academic discipline Academic subjects have made me aware of a number of connections and patterns in the have made me scriptures that, without scholarly study, would have remained hidden from me. Perhaps that happens because I am a student of language, and aware of a number the scriptures are written in language, but I think such experiences are of connections and not limited to people in the English Department. Nevertheless, in my case, insights have come as a result of studying and teaching literature, patterns in the and also as a result of studying and teaching writing. scriptures. For this occasion, I will focus on just one of the areas I have learned as a student of language. That area of scholarship is formal logic.I nterestingly, I have been acquainted with some academicians who laud scholarship but avoid formal logic with the same care they take to avoid salmonella poisoning. The contention is that they can “sense” when an argument is right or wrong, and they do not need to be encumbered with all of the tools and paraphernalia. -

Worth Their Salt, Too

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DigitalCommons@USU Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2000 Worth Their Salt, Too Colleen Whitley Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Whitley, C. (2000). Worth their salt, too: More notable but often unnoted women of Utah. Logan: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Worth Their Salt, Too More Notable but Often Unnoted Women of Utah WORTH THEIR SALT, TOO More Notable but Often Unnoted Women of Utah Edited by Colleen Whitley UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS Logan, Utah 2000 Copyright © 2000 Utah State University Press “Marion Davis Clegg: The Lady of the Lakes” copyright © 2000 Carol C. Johnson All rights reserved Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 84322-7800 All royalties from the sale of this book will be donated to support the Exhibits office of the Utah State Historical Society. Cover photos: Marion Davis Clegg, courtesy of Photosynthesis; Verla Gean FarmanFarmaian, courtesy of Gean FarmanFarmaian; Ora Bailey Harding, courtesy of Lurean S. Harding; Alberta Henry, courtesy of the Deseret News; Esther Peterson, courtesy of Paul A. Allred; Virginia Sorensen, courtesy of Mary Bradford Typography by WolfPack Printed in Canada Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Worth their salt, too : more notable but often unnoted women of Utah / edited by Colleen Whitley. -

Heber C. Kimball and Family, the Nauvoo Years

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 15 Issue 4 Article 7 10-1-1975 Heber C. Kimball and Family, The Nauvoo Years Stanley B. Kimball Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Part of the Mormon Studies Commons, and the Religious Education Commons Recommended Citation Kimball, Stanley B. (1975) "Heber C. Kimball and Family, The Nauvoo Years," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 15 : Iss. 4 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol15/iss4/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Kimball: Heber C. Kimball and Family, The Nauvoo Years heber C kimball and family the nauvoo years stanley B kimball As one of the triumviritriumvirsof early mormon history heber C kimball led an adventuresome if not heroic life by the time he settled in nauvoo during may of 1839 he had been a black- smith and a potter had married and had five children two of whom had died he had lived in vermont new york ohio and missouri and had left or been driven out of homes in each state he had served fourteen years in a horse company of the new york militia had joined and left the close com- munion baptist church accepted mormonism had gone on four missions including one to england had become an apostle hadbad helped build the temple at kirtland had ded- icated the temple site at