MALCOLM CHASE Unemployment Without Protest: the Ironstone Mining Communities of East Cleveland in the Inter-War Period

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Nortli Skgfton PC Cup.Winners!

Edition No. 15 A UGUST 1996 A NEWSPAPER for NORTH SKELTON & LAYLAND 'Nortli Skgfton PC Cup.Winners! On a wet and miserable evening, nearly all the village turned out to applaud the two teams of footballers on their achievements in what was one ofthe most successful seasons ever for North Skelton FC - 1953/54. The players proudly displaying the trophies won were driven around the village on the back ofNorth Skelton Mines engineering shop's lorry proceeded by North Skelton Band.This was followed by a reception and presentation at the Village Hall of individual trophies to team members by a senior official of the North Riding FA. An excellent meal was provided by the lady supporters and committee members. Names of persons riding on the lorry from left to right: Sitting - Wilf Stunnan, Owen Laffey?, Joe Hughes, 'Chiggy" Thomas. Standing - John Chamberlain, Norman Stunnan, Bill Fraser, Jim Ramage, Colin Berwick, Keith Ovington, Len Douglass (displaying The North Riding Amateur Cup), and Jack May (McMillan Cup) . Nurse Wardaugh. the then District Nurse, can be seen standing on her front doorstep lending her support. ~~~ Poge 2 ~~~~~~~~~~~ Tile Keg ~ ~ ~~ Hello everyone! Our New Local 'Bobby' Thank you all again for your donations, espe cially to senior citizen Effie May Brough who First of all may I introduce myself to you always gives so generously. all. My name is Paul Bland and following the retirement of PC Tom Towers in A visit from J immy . March I was chosen as his replacement to Hauxwell, and many be your local bobby on the beat. -

Action North Skelton

ISS UE NO 30 AUGUST2001 THE A NEWSPAPER FOR NORTH SKELTON & LAYLAND All aerial view ofNorth Skelton & Layland - photo by Stuart MacMillall, 4th July 2001 'Fun Day' Don ami I have received numerous e-ntails from readers at the Bull's Head all over the British Isles ami around the world. We ap preciate each one sent and try to reply as quickly as pos sible. I am particularly grateful for all the lovely letters you semi to me - thankyou. Saturday 18th August at the Bull's Head, North Skelton Don't forget ifyou would like to send a Christmas or Congratulations message to anyone please let me have it by the beginning ofOctober. This facility remainsfree to lOam: Car Boot Sale, Cake Competition, North Skelton ami Layland residents - there is a small 'Feed the Goal', Tombola, charge of£2.00 to anyone else. Tea, Coffee and more ... On 3rd May 2001, Eddie Britton presented me with a cheque for £25 on behalf of the R.O.A.B. St Thomas' Lodge, Green bill, Skelton Green - thankyou so much. 12.30pm: Bar B Q, Speed Pool, Greasy Pole Knockout: Pool, Dominoes &Darts Your donations are still very much appreciated - please make cheques payable to 'The Key'. Children's races: Egg & Spoon, 3-Legged, plus much more ... 7pm: Adults' Fancy Dress Disco Editor: Norma Templeman, 7Bolckow St, North Skelton, Saltburn, Cleveland TS12 2AN Cowboy/Girl & Indian Tel: 01287653853 Assistant Editor: Don Burluraux, 8 North Terrace, Tickets on Sale now - only £1.50 Skelton, Saltburn, Cleveland TS12 2ES Tel: 01287652312 9pm: Raffle Draw and 'The Full Monty' or e-mail: [email protected] Can you drink a 'yardofale I ? Photos from 'The Key' can be found on the Internet Come andshow us how it's done then! the website address is: "ttp:IIII'JI'JI'.IJIIrlllraIlX1.fi·eeserl'e. -

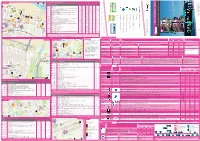

Towards Middlesbrough Bus Station Stand 11

SAPPHIRE - Middlesbrough to Easington 5, 5, 5A Middlesbrough to Skelton 5A via Guisborough Monday to Friday - towards Easington Ryelands Park 5 5 5 5 5A 5 5A 5 5A 5 5 5 5A 5 5A 5 5A 5 5A 5 Middlesbrough Bus Station Stand 8 0622 0652 0722 0752 0807 0827 42 57 12 27 1412 1432 1447 1502 1517 1532 1547 1602 1617 1632 Middlesbrough Centre Square 0626 0656 0726 0756 0811 0831 46 01 16 31 1416 1436 1451 1506 1521 1536 1551 1606 1621 1636 North Ormesby Market Place 0631 0701 0731 0803 0818 0838 53 08 23 38 1423 1443 1458 1513 1528 1543 1558 1613 1628 1643 Ormesby Crossroads 0638 0708 0740 0814 0829 0847 02 17 32 47 1432 1452 1507 1522 1537 1552 1607 1622 1637 1657 Nunthorpe Swans Corner Roundabout 0642 0712 0744 0820 0835 0851 06 21 36 51 1436 1456 1511 1526 1541 1556 1611 1626 1641 1701 Guisborough Market Place 0653 0723 0756 0832 0847 0903 18 33 48 03 1448 1508 1523 1538 1553 1608 1623 1638 1653 1713 Skelton Co-op 0703 0733 0806 0842 0857 0913 28 43 58 13 1458 1518 1533 1548 1603 1618 1633 1648 1703 1723 Then past Hollybush Estate The Hollybush -- -- -- -- 0859 -- at 30 -- 00 -- each 1500 -- 1535 -- 1605 -- 1635 -- 1705 -- New Skelton Rievaulx Road End -- -- -- -- -- -- these -- -- -- -- hour -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- mins until North Skelton The Bulls Head 0707 0737 0810 0846 -- 0917 -- 47 -- 17 -- 1522 -- 1552 -- 1622 -- 1652 -- 1727 Brotton The Green Tree 0711 0741 0815 0851 -- 0922 -- 52 -- 22 -- 1527 -- 1557 -- 1627 -- 1657 -- 1732 Carlin How War Memorial 0715 0745 0819 0855 -- 0926 -- 56 -- 26 -- 1531 -- 1601 -- 1631 -- 1701 -- 1736 -

Down Memorylane

Edition No. 6 August 1993 A NEWSPAPER FOR NORTH SKELTON & LAYLAND Down MemoryLane I wonder how many of you recognise some of the characters from this photograph kindly supplied to us hy Len Douglas. Sadly. nUInY of them are no longer with us bnt I'm sure a lot of you will remember old friends and even relatives. I wonder. also. if any of you know the occasion for which the photo was taken and the approximate dale. Have It good look at the photograph and sec who you recognise. Len has named as many as he can remember on Page I. Ir he's wrong with anyone or if ynll know someone we don't then please let us know. Also if you have ally' old school or (CHIlI photographs \II' local interest we'd love to hear Irom you and publish them in future lAliliuns of 'The Key'. _- fYlw d~!f -----.l1li....----- :!IarJ,f} ;J Hello Everybody, I am sure that our photo gallery in the centre pages will cause a lot of interest so if any of you have any information or stories to tell on any 0 f the pho tos , please let me know (Norma Templeman ~ Tel: 653853). Thank you to all who loaned us the photos. We now have a well run team with regular writers. Thank Clr Norman Lantsberry present you and keep on writing, ing ~ cheque to The Key, being ple~se . keJep the donations rece~ved by our representative com~ng ~n. Tony Chapman. A welcome grant from the Community & Economic ~CA-- Grant Fund towards producing our village paper. -

Redcar & Cleveland Ironstone Heritage Trail

Redcar & Cleveland Ironstone Heritage Trail Car and Walk Trail this is Redcar & Cleveland Redcar & Cleveland Ironstone Heritage Trail The History of Mining Ironstone Villages Ironstone mining began in Redcar & A number of small villages grew up in Cleveland in the 1840s, with the East Cleveland centred around the Redcar & Cleveland collection of ironstone from the ironstone mines and the differing Ironstone Heritage Trail foreshore at Skinningrove. A drift mine facilities available at these villages. celebrates the iron and steel was opened in the village in 1848. The Those that were established by ironstone industry on Teesside grew Quaker families did not permit public history of the Borough. Linking rapidly following the discovery of the houses to be built. At New Marske, Eston and Skinningrove, the Main Seam at Eston on 8th June 1850 the owners of Upleatham Mine, the by John Vaughan and John Marley. In two areas that were both Pease family, built a reading room for September a railway was under the advancement of the mining integral to the start of the construction to take the stone to both industry, the trail follows public the Whitby-Redcar Railway and the community. In many villages small schools and chapels were footpaths passing industrial River Tees for distribution by boat. The first stone was transported along the established, for example at Margrove sites. One aspect of the trail is branch line from Eston before the end Park. At Charltons, named after the that it recognises the of 1850. Many other mines were to first mine owner, a miners’ institute, commitment of many of the open in the following twenty years as reading room and miners’ baths were the industry grew across the Borough. -

Industry in the Tees Valley

Industry in the Tees Valley Industry in the Tees Valley A Guide by Alan Betteney This guide was produced as part of the River Tees Rediscovered Landscape Partnership, thanks to money raised by National Lottery players. Funding raised by the National Lottery and awarded by the Heritage Lottery Fund It was put together by Cleveland Industrial Archaeology Society & Tees Archaeology Tees Archaeology logo © 2018 The Author & Heritage Lottery/Tees Archaeology CONTENTS Page Foreword ........................................................................................ X 1. Introduction....... ...................................................................... 8 2. The Industrial Revolution .......... .............................................11 3. Railways ................................................................................ 14 4. Reclamation of the River ....................................................... 18 5. Extractive industries .............................................................. 20 6. Flour Mills .............................................................................. 21 7. Railway works ........................................................................ 22 8. The Iron Industry .................................................................... 23 9. Shipbuilding ........................................................................... 27 10. The Chemical industry ............................................................ 30 11. Workers ................................................................................. -

NORTH RIDING YORKSHIRE. NORTH ORMESBY. 283 ORMESBY Is a Parish and Pleasant Village on the James Worsley Pennyman Esq

DI'BEOTORY. J NORTH RIDING YORKSHIRE. NORTH ORMESBY. 283 ORMESBY is a parish and pleasant village on the James Worsley Pennyman esq. who is lord of the manor, road from Stockton to Redcar, about I mile east from and Lord Furness, of Grantley Hall, Ripon, are the the Ormesby station on the Middlesbrough and Guis chief landowners. The soil is clayey; subsoil, strong borough branch of the North Eastern railway, 3! south clay. The chief crops are wheat, barley, oati and east from Middlesbrough, 6 north-by-west from (luis beans. The area of .the civil parish and Urban Dis~rict borough, 7 east-south-east from Stockton and 8 south is 2,833 acres, including North Ormesby; rateable value, west from Redcar, in the Cleveland division of the Rid £4o,679; the population in 1901 was 9,482 and of the ing, west division of the Langbaurgh liberty, petty ses e<lClesiastical parish 547, and in : 9tr, of the civil parish, sional division of Langbaurgh North, Middlesbrough 14,582 and of the ecclesiastical parish 528. union and county court district, rural deanery of Mid Parish Clerk, Robert Hardy. dlesbrough, archdeaconry of Cleveland and diocese of Post & M. 0. Office (letters should have Yorks added). York. Under the provisions of the "Local Government -Miss Amy Sandel'l3on, sub-postmistress. Letters Act, r.B94," that portion of the original Ormesby civil arrive at 6.40 a.m. & 12.40 & 5.20 p.m. & are dis• parish included within the Middlesbrough municipal patched at rr.w a.m. & 12.40 & 6.5 & 9 p.m. -

B Us Train M Ap G Uide

R d 0 100 metres Redcar Town Centre Bus Stands e r n Redcar m d w G d B d e o i i e a u Stand(s) i w r t r 0 100 yards h c e s Service l t e w . h c t t Key destinations u c Redcar Wilton High Street Bus Railway Park e t i y . number e m t N Contains Ordnance Survey data e b t o e u © Crown Copyright 2016 Clock Street East Station # Station Avenue t e e v o l s g G y s Regent x l N t e Digital Cartography by Pindar Creative o 3 w i t y o m c ◆ Marske, Saltburn, Skelton, Lingdale A–L Q ––– f o e m Cinema B www.pindarcreative.co.uk a r u e o ©P1ndar n t o e l u r d v u s m T s e r Redcar Redcar Clock C–M R ––– m f r s a r o y c e P C e r n t o Beacon m s e r r y e o . b 22 Coatham, Dormanstown, Grangetown, Eston, Low Grange Farm, Middlesbrough F* J M R* 1# –– a m o d e o t i v a u u l n t e b e o r c r s t l s e b Ings Farm, The Ings , Marske , New Marske –HL Q ––– i . ◆ ◆ ◆ i T t l . n d c u Redcar and Cleveland o e i . u a p p r e a N n e Real Opportunity Centre n o 63 Lakes Estate, Eston, Normanby, Ormesby, The James Cook University Hospital, D G* H# K* –2– – e e d j n E including ShopMobility a r w p Linthorpe, Middlesbrough L# Q# n S W c r s i t ’ Redcar Sands n d o o r e S t e St t t d e m n t la e 64 Lakes Estate, Dormanstown, Grangetown, Eston, South Bank, Middlesbrough F* J M P* 1# 2– c Clev s S a e n d t M . -

1911 Census for England & Wales

1911 Census For England & Wales Relationship Children Number on Years Total Children Children Employer or Working at Number Surname First Name to Head of Birth year Age Marriage Who Have Occupation Industry Place Of Birth Address Nationality Infirmity Location Schedule Married Born Alive Still Living Worker Home Rooms Family Died 29 Ackroyd Eliza Head 1843 68 Widow 12 8 5 3 Bishop Monkton, Yorkshire Pilots Cottage 6 Great Ayton 4 Adams Minnie Housemaid 1887 24 Single Housemaid Aldershot, Hampshire Cleveland Lodge 22 Great Ayton Friends School Aisnley Eva Scholar 1896 15 Single At Boarding School Durham Friends School Great Ayton Friends School Alderson Reuben Scholar 1897 14 Single At Boarding School Shildon,Durham Friends School Great Ayton 158 Alexander Edward Son 1893 18 Single Pumping Engineer Ironstone Mine Worker New Marske, Yorkshire 1, Monkabeque Road Great Ayton 158 Alexander Emma Wife 1867 24 Wife 25 5 4 1 Coatham, Yorkshire 1, Monkabeque Road Great Ayton 158 Alexander Florance Daughter 1902 9 School New Marske, Yorkshire 1, Monkabeque Road Great Ayton 158 Alexander Wilfrid Son 1897 14 Blacksmith Striker Ironstone Mine Worker New Marske, Yorkshire 1, Monkabeque Road Great Ayton 158 Alexander William Head 1863 48 Head Pipe Fitter Ironstone Mine Worker Manningford, Wiltshire 1, Monkabeque Road 5 Great Ayton 276 Alliram Francis Elizabeth Servant 1887 24 Single Housemaid Guisborough, Yorkshire Ayton House, Great Ayton 11 Great Ayton Friends School Ames Winifred Alice Housemaid 1890 21 Single Housemaid Worker Loose Valley,Kent Friends -

Sacred Heart Catholic Secondary Home to School Transport 2020-21

Sacred Heart Catholic Secondary Part of the Nicholas Postgate Catholic Academy Trust. Home to School Transport 2020-21 A guide for young people, parents and carers Sacred Heart Catholic Secondary Mersey Road REDCAR TS10 1PJ pg. 1 Introduction The School has arranged transport provision for areas in East Cleveland for the academic year 2020-21, at the request of parents/carers. This guide provides information on the transport service we have put in place and outlines the standards that we expect in return. This ensures that we provide a service that is safe, comfortable, and reliable and represents value for money for parents and carers. The guide is divided into four parts: Part 1 – Information about the School Transport service Part B – Passenger Code of Conduct Appendix 1 – Bus Timetables Appendix 2 – School/Parent/Passenger Agreement Dedicated Bus Service The Trust has appointed Skelton Coaches to run four buses for home to school transport. The routes were based on numbers of applications and home locations of the students wishing to use a service. The routes have been designated as follows: Route 33 – Liverton Mines – Skinningrove - Brotton – Skelton - New Marske Route 34 – Easington – Loftus - Carlin How - Saltburn Route 35 – Guisborough - Dunsdale Route 36 – Boosbeck – Guisborough – Upleatham - Marske Timetables for the academic year 2020-21 can be found at Appendix 1. Cost of Travel The cost of travel for the academic year 2020-21 is £560 per seat. Payment of the annual fee does entitle the student to travel on an alternative route than the one issued. This can be paid in full or in ten monthly instalments. -

York-Thirsk-Northallerton 58

YORK-THIRSK-NORTHALLERTON 58 Operated by John Smith & Sons, Monday To Friday (not Bank Holidays) Service No 58 58 58 58 58 58 58 Operator JSS JSS JSS JSS JSS JSS JSS Days CD NCD CD NCD Askham Bryan College - 0900 - - - 1640 - Dringhouses, York College - 0910 - - - 1645 - York, Railway Station - 0925 0925 1105 1405 1700 1700 York, Exhibition Square - 0926 0926 1106 1406 1702 1702 Clifton Green - 0933 0933 1113 1413 1710 1710 Shipton by Beningbrough - 0939 0939 1119 1419 1720 1720 Easingwold Market Place - 0950 0950 1130 1430 1730 1730 Carlton Husthwaite, Lane End - 0957 0957 1140 1440 1740 1740 Bagby, Lane End - 1000 1000 1145 1445 1744 1744 Thirsk, Industrial Park - 1003 1003 1148 1448 1747 1747 Thirsk, Market Place 0705 1005 1005 1150 1450 1750 1750 Thornton le Street - - - - - 1755 1755 Thornton le Moor, Lane End - - - - - 1800 1800 Northallerton, High St,Post Office 0720 - - - - 1808 1808 Northallerton, Buck Inn 0722 - - - - 1810 1810 Notes: CD College Days Only JSS John Smith & Sons NCD Non College Days NORTHALLERTON - THIRSK - YORK 58 Operated by John Smith & Sons, Monday To Friday (not Bank Holidays) Service No 58 58 58 58 58 58 58 Operator JSS JSS JSS JSS JSS JSS JSS Days CD NCD CD NCD Northallerton, Buck Inn 0725 0725 - - - - 1820 Northallerton,High St, Nags Head 0726 0726 - - - - 1821 Thornton le Moor, Lane End 0731 0731 - - - - 1826 Thornton le Street 0735 0735 - - - - 1830 Thirsk, Market Place 0740 0740 1010 1300 1530 1530 1835 Thirsk, Long Street 0742 0742 1012 1302 - - - Thirsk, Industrial Park 0743 0743 1013 1303 - - - Bagby, -

MIDDLESBROUGH. 163 Population Was 25 J in 2:8N, 3.5; in 1821 1 40; in 1831 1 154; X88r, 18 8 :£

• . DIRECTORY. J NORTH RIDING YORKSHIRE: MIDDLESBROUGH. 163 population WaS 25 J in 2:8n, 3.5; in 1821 1 40; in 1831 1 154; x88r, 18 8 :£.. in 1841,_ 5,463; in :1851,.- 7,631 l in x86r~ 8,!!92; in 1871, Eswn, part of _. .• -·.,. ~· .. ....,, 2,88o 71311 39,284; in r88t, 55,288, and in x89r, 75,516. Linthorpe, part of ;., ......._ 18,334 25,178 The population of the municipal and parliamentary Marton, part of ,,~,, ....... , ... 458 6ox borough in x881 and 189:r, was as follows : ' Middlesbrough .1, ••• , .......... 36,63x 49,6r3 1881. 189:t. N ormanby, part of ..~ ...- •. ., 6,455 7.884 Linthorpe, part of ........... t18,717 t25,173 Ormesby, part of ........... 7,387 8,34+ Marton, part of ·········-·•·.- 531 i. 001 Middlesbrough ............. .. 36,631 49,613 Parliamentary limits ... 72 • 145 98,931 Ormesby, part of ........... 55 I24 - t Including 16 officers and 6o7 inmates in the Workhouse,. ;Municipal limits ..... ~ . ..J Parish Clerk of Middlesbrough, vacani. 55.934 75.516 - Official Establishments, Local Institutions &c. PosT, M. 0. & T. 0., S. B. Annuity & Insurance Office, Post tNorth street, John Westrip, receiver, 5.3o, 9.30 & II.JO Office buildingB.-George Brooks, postmaster a.m.; I. 15, g, 5j 6. J5, 7, 7-45 & 9.20 p.m. Sunday, 4·30 MA.ILS DISPATCHED-BOX CLEARED. tRussellstreetl William R. Meggeson, receiver, 5.30, 9.30 Redcar, Eston Junction, Grangetown, Marton, Nunthorpe & 11.30 a.m.; ~.15, 3, s, 6, 7, 8 & 9.20 p.m. · Sunday, & South Bank, 5-55 a.m.; Cowpen-Bewley, Hemlington, 4 p.m Linthorpe Estate, Port Clarence, Haverton Hill, Ormesby, t*Sussex street, Laverick Brothers, receivers, 5-300 9.30 & Norman by,.