Working the Plate: Another View, Part 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2 Umpire System (Rotation) Fast Pitch and Modified Pitch the 2 Umpire System Requires That Umpires Move Into Positions Appropriate for Each Play

2 Umpire System (Rotation) Fast Pitch and Modified Pitch The 2 umpire system requires that umpires move into positions appropriate for each play. The information referring to positioning and the calling of plays is written for ideal circumstances and for the best possible positioning for the majority of plays. Proper positioning can be achieved if you think in terms of 'keeping the play in front of you'. In order to do this there are four basic elements that must be kept in your vision. 1 The ball 2 The defensive player making the play 3 The batter runner or runner and 4 The base or area where the above elements meet Three Basic Principles There are three basic principles that apply to the Two Umpire Rotation System; the division principle, the infield/outfield principle and the leading runner principle. 1 The Division Principle The home Plate Umpire takes all calls at Home Plate and third base and the Base Umpire takes all calls at first and second bases. Exceptions 1 When the Batter Runner goes to third base, the Base Umpire then takes Batter Runner to third 2 On an Infield play, the Base Umpire takes the first call on a base, even if it is at third base 3 When a Runner steals to third base, the Base Umpire takes the call 4 If you must deviate, communicate your deviation to your partner May 1. 2017 Fast Pitch Adapted from Softball Australia Page 1 2 The Infield/Outfield Principle When the ball is in the infield, the Base Umpire moves or stays in the outfield. -

2020 Umpire Manual

UMPIRE MANUAL LETTER FROM THE USA SOFTBALL NATIONAL OFFICE USA Softball Umpires We want to welcome you to the 2020 Softball Season. Thank you for being a USA Softball Umpire as it is because of you we continue to have the best dressed, best trained and dedi- cated umpires in the country. Without all of you we could not continue to make the umpire program better every year. From those who umpire USA Softball league softball night in and night out, those who represent us on the National Stage and those who umpire on the World Stage you are the ones that show everyone we are the best umpires in the world of Softball. We continue to look at ways to help our program get better every year. We have a new agenda for the USA Softball National Umpire Schools that is working well. We have also revamped the Fast Pitch Camps and Slow Pitch Camps, to be more advanced in techniques and philosophies targeted to those umpires who want to take the next step in their umpire career. We have established a new committee to revamp the Slow Pitch Camp agenda to make it centered around the areas of Slow Pitch Softball that need the most attention. As our upper level Slow Pitch opportunities grow, we must design a camp around working that upper level while still helping the umpires trying to get to that level. This is the third year for the umpire manual to be in electronic form posted on the web. It is also available with the rule book app that is updated every year. -

AROUND the HORN News & Notes from the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum September Edition

NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME AND MUSEUM, INC. 25 Main Street, Cooperstown, NY 13326-0590 Phone: (607) 547-0215 Fax: (607)547-2044 Website Address – baseballhall.org E-Mail – [email protected] NEWS Brad Horn, Vice President, Communications & Education Craig Muder, Director, Communications Matt Kelly, Communications Specialist P R E S E R V I N G H ISTORY . H O N O R I N G E XCELLENCE . C O N N E C T I N G G ENERATIONS . AROUND THE HORN News & Notes from the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum September Edition Sept. 17, 2015 volume 22, issue 8 FRICK AWARD BALLOT VOTING UNDER WAY The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s Ford C. Frick Award is presented annually since 1978 by the Museum for excellence in baseball broadcasting…Annual winners are announced as part of the Baseball Winter Meetings each year, while awardees are presented with their honor the following summer during Hall of Fame Weekend in Cooperstown, New York…Following changes to the voting regulations implemented by the Hall of Fame’s Board of Directors in the summer of 2013, the selection process reflects an era-committee system where eligible candidates are grouped together by years of most significant contributions of their broadcasting careers… The totality of each candidate’s career will be considered, though the era in which the broadcaster is deemed to have had the most significant impact will be determined by a Hall of Fame research team…The three cycles reflect eras of major transformations in broadcasting and media: The “Broadcasting Dawn Era” – to be voted on this fall, announced in December at the Winter Meetings and presented at the Hall of Fame Awards Presentation in 2016 – will consider candidates who contributed to the early days of baseball broadcasting, from its origins through the early-1950s. -

2020 MLB Ump Media Guide

the 2020 Umpire media gUide Major League Baseball and its 30 Clubs remember longtime umpires Chuck Meriwether (left) and Eric Cooper (right), who both passed away last October. During his 23-year career, Meriwether umpired over 2,500 regular season games in addition to 49 Postseason games, including eight World Series contests, and two All-Star Games. Cooper worked over 2,800 regular season games during his 24-year career and was on the feld for 70 Postseason games, including seven Fall Classic games, and one Midsummer Classic. The 2020 Major League Baseball Umpire Guide was published by the MLB Communications Department. EditEd by: Michael Teevan and Donald Muller, MLB Communications. Editorial assistance provided by: Paul Koehler. Special thanks to the MLB Umpiring Department; the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum; and the late David Vincent of Retrosheet.org. Photo Credits: Getty Images Sport, MLB Photos via Getty Images Sport, and the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Copyright © 2020, the offiCe of the Commissioner of BaseBall 1 taBle of Contents MLB Executive Biographies ...................................................................................................... 3 Pronunciation Guide for Major League Umpires .................................................................. 8 MLB Umpire Observers ..........................................................................................................12 Umps Care Charities .................................................................................................................14 -

The Ballgame

www.birminghamtrackclub.com Birmingham’s Area Running Club BIRMINGHAM TRACK CLUB www.myspace.com/birminghamtrackclub www.rrca.org VOL. 32 AUGUST 2008 ISSUE 7 TAKE ME OUT TO thE ballgamE Club takes road trip to see Atlanta Braves – By Michele Parr, Treasurer through the efforts of Danny Guccione’s tight strike zone runs were as exciting as it got Haralson and John Gordon, the made it a long day for Braves’ for the home crowd. What do you get when you Braves trip was brought back by pitchers Jo-Jo Reyes and Buddy But for many who made the put a few dozen BTC members, member request. Carlyle, who gave up 12 of the trip, it wasn’t just about base- their families, and their friends If you’re a Braves’ fan, it 15 runs in just 3 innings. The ball. Some, like Patty Landry, on a bus, point it east, and ride wasn’t the best baseball you’ve tough ball/strike calls finally had never been to a Braves for three hours? A great day seen them play. It can be tough got to Braves’ manager Bobby game. “The cost was a great at the ballpark! That’s exactly sitting in the July heat watching Cox, who got ejected for the deal, so why not go?” she said. what happened on July 20. Af- the home team get clobbered 141st time in his career. That Jason McLaughlin, who had ter a couple of years without it, 15-6. Home plate umpire Chris and Mark Texiera’s two home never been to Turner Field, joined Cindy Sullivan and Jus- tin Arcury for a guided tour of the stadium provided by Terri Chandler, who used to live in Atlanta. -

April 2021 Auction Prices Realized

APRIL 2021 AUCTION PRICES REALIZED Lot # Name 1933-36 Zeenut PCL Joe DeMaggio (DiMaggio)(Batting) with Coupon PSA 5 EX 1 Final Price: Pass 1951 Bowman #305 Willie Mays PSA 8 NM/MT 2 Final Price: $209,225.46 1951 Bowman #1 Whitey Ford PSA 8 NM/MT 3 Final Price: $15,500.46 1951 Bowman Near Complete Set (318/324) All PSA 8 or Better #10 on PSA Set Registry 4 Final Price: $48,140.97 1952 Topps #333 Pee Wee Reese PSA 9 MINT 5 Final Price: $62,882.52 1952 Topps #311 Mickey Mantle PSA 2 GOOD 6 Final Price: $66,027.63 1953 Topps #82 Mickey Mantle PSA 7 NM 7 Final Price: $24,080.94 1954 Topps #128 Hank Aaron PSA 8 NM-MT 8 Final Price: $62,455.71 1959 Topps #514 Bob Gibson PSA 9 MINT 9 Final Price: $36,761.01 1969 Topps #260 Reggie Jackson PSA 9 MINT 10 Final Price: $66,027.63 1972 Topps #79 Red Sox Rookies Garman/Cooper/Fisk PSA 10 GEM MT 11 Final Price: $24,670.11 1968 Topps Baseball Full Unopened Wax Box Series 1 BBCE 12 Final Price: $96,732.12 1975 Topps Baseball Full Unopened Rack Box with Brett/Yount RCs and Many Stars Showing BBCE 13 Final Price: $104,882.10 1957 Topps #138 John Unitas PSA 8.5 NM-MT+ 14 Final Price: $38,273.91 1965 Topps #122 Joe Namath PSA 8 NM-MT 15 Final Price: $52,985.94 16 1981 Topps #216 Joe Montana PSA 10 GEM MINT Final Price: $70,418.73 2000 Bowman Chrome #236 Tom Brady PSA 10 GEM MINT 17 Final Price: $17,676.33 WITHDRAWN 18 Final Price: W/D 1986 Fleer #57 Michael Jordan PSA 10 GEM MINT 19 Final Price: $421,428.75 1980 Topps Bird / Erving / Johnson PSA 9 MINT 20 Final Price: $43,195.14 1986-87 Fleer #57 Michael Jordan -

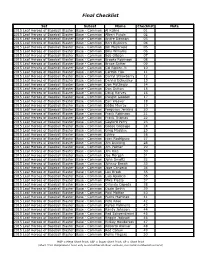

Final Checklist

Final Checklist Set Subset Name Checklist Note 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Al Kaline 01 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Albert Pujols 02 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Andre Dawson 03 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Bert Blyleven 04 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Bill Mazeroski 05 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Billy Williams 06 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Bob Gibson 07 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Brooks Robinson 08 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Bruce Sutter 09 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Cal Ripken Jr. 10 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Carlton Fisk 11 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Darryl Strawberry 12 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Dennis Eckersley 13 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Don Mattingly 14 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Don Sutton 15 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Doug Harvey 16 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Dwight Gooden 17 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Earl Weaver 18 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Eddie Murray 19 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Ferguson Jenkins 20 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Frank Robinson 21 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Frank Thomas 22 2015 Leaf Heroes of -

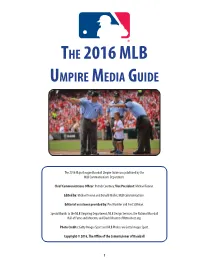

2016 Umpire Media Guide

THE 2016 MLB UMPIRE MEDIA GUIDE The 2016 Major League Baseball Umpire Guide was published by the MLB Communications Department. Chief Communications Offi cer: Patrick Courtney; Vice President: Michael Teevan. Edited by: Michael Teevan and Donald Muller, MLB Communications. Editorial assistance provided by: Paul Koehler and Fred Stillman. Special thanks to the MLB Umpiring Department; MLB Design Services; the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum; and David Vincent of Retrosheet.org. Photo Credits: Getty Images Sport and MLB Photos via Getty Images Sport. Copyright © 2016, The Offi ce of the Commissioner of Baseball 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS MLB Executive Biographies ................................................................................................................................. 3 MLB Umpire Observers ...................................................................................................................................... 12 Umpire Initiatives .............................................................................................................................................. 14 Umpires in the National Baseball Hall of Fame .................................................................................................. 16 Retired Uniform Numbers ................................................................................................................................. 19 MLB Umpire Roster .......................................................................................................................................... -

Hey Blue On-Line Fall 2018

Volume 9 Edition 1 September 2018 Membership Record It’s a record folks! BCBUA membership has topped 1600 for the first time in history. While final num- bers for the year will not be available until after the fiscal year closes Septem- ber 30, the online database shows over 1600 members to date. Previously the all time high had been 1587. In 2017, the BCBUA saw a sharp increase in umpire numbers to 1500, and this year’s jump is equally im- pressive. SCHEURWATER HIRED BY MLB Regina’s Stu Scheurwater was Victoria’s Ian Lamplugh hired to the full time MLB worked over 200 games as staff prior to the 2018 season. a call up in the early He becomes the first Canadian 2000’s. There are just a hired full time since Jim handful of Canadian McKean of Montreal. umpires working in the minors in 2018. Sean Sullivan gives a “Thumbs Up” to 2018 BCBUA AGM DATE SET! The BCBUA Annual location. Please come out and meet your fellow umpires. General Meeting will be Election of officers and a held in Kelowna on : an update on our bylaw review are up for voting AGM October 27, 2018 this year. In addition, our annual awards will be pre- 1:00 p.m. sented along with the vari- Oct. 27 1pm ous committee reports. A PUBLICATION OF THE BCBUA Check the website for the Kelowna. BC Inside this issue: Special points of interest: West Coast League Finals 2 Baseball Canada Umpire of the Week National Umpire Assignments 3 Grand Forks floods—tournament cancelled Pictures, Pictures, Pictures…. -

Kit Young's Sale #154

Page 1 KIT YOUNG’S SALE #154 AUTOGRAPHED BASEBALLS 500 Home Run Club 3000 Hit Club 300 Win Club Autographed Baseball Autographed Baseball Autographed Baseball (16 signatures) (18 signatures) (11 signatures) Rare ball includes Mickey Mantle, Ted Great names! Includes Willie Mays, Stan Musial, Eddie Murray, Craig Biggio, Scarce Ball. Includes Roger Clemens, Williams, Barry Bonds, Willie McCovey, Randy Johnson, Early Wynn, Nolan Ryan, Frank Robinson, Mike Schmidt, Jim Hank Aaron, Rod Carew, Paul Molitor, Rickey Henderson, Carl Yastrzemski, Steve Carlton, Gaylord Perry, Phil Niekro, Thome, Hank Aaron, Reggie Jackson, Warren Spahn, Tom Seaver, Don Sutton Eddie Murray, Frank Thomas, Rafael Wade Boggs, Tony Gwynn, Robin Yount, Pete Rose, Lou Brock, Dave Winfield, and Greg Maddux. Letter of authenticity Palmeiro, Harmon Killebrew, Ernie Banks, from JSA. Nice Condition $895.00 Willie Mays and Eddie Mathews. Letter of Cal Ripken, Al Kaline and George Brett. authenticity from JSA. EX-MT $1895.00 Letter of authenticity from JSA. EX-MT $1495.00 Other Autographed Baseballs (All balls grade EX-MT/NR-MT) Authentication company shown. 1. Johnny Bench (PSA/DNA) .........................................$99.00 2. Steve Garvey (PSA/DNA) ............................................ 59.95 3. Ben Grieve (Tristar) ..................................................... 21.95 4. Ken Griffey Jr. (Pro Sportsworld) ..............................299.95 5. Bill Madlock (Tristar) .................................................... 34.95 6. Mickey Mantle (Scoreboard, Inc.) ..............................695.00 7. Don Mattingly (PSA/DNA) ...........................................99.00 8. Willie Mays (PSA/DNA) .............................................295.00 9. Pete Rose (PSA/DNA) .................................................99.00 10. Nolan Ryan (Mill Creek Sports) ............................... 199.00 Other Autographed Baseballs (Sold as-is w/no authentication) All Time MLB Records Club 3000 Strike Out Club 11. -

Kit Young's Sale #131

page 1 KIT YOUNG’S SALE #131 1952-55 DORMAND POSTCARDS We are breaking a sharp set of the scarce 1950’s Dormand cards. These are gorgeous full color postcards used as premiums to honor fan autograph requests. These are 3-1/2” x 5-1/2” and feature many of the game’s greats. We have a few of the blank back versions plus other variations. Also, some have been mailed so they usually include a person’s address (or a date) plus the 2 cent stamp. These are marked with an asterisk (*). 109 Allie Reynolds .................................................................................. NR-MT 35.00; EX-MT 25.00 110 Gil McDougald (small signature) ..................................................................... autographed 50.00 110 Gil McDougald (small signature) ..............................................................................NR-MT 50.00 110 Gil McDougald (large signature) ....................................................... NR-MT 30.00; EX-MT 25.00 111 Mickey Mantle (bat on shoulder) ................................................. EX 99.00; GD watermark 49.00 111 Mickey Mantle (batting) ........................................................................................ EX-MT 199.00 111 Mickey Mantle (jumbo 6” x 9” blank back) ..................................................... EX-MT rare 495.00 111 Mickey Mantle (jumbo 6” x 9” postcard back) ................................................ GD-VG rare 229.00 111 Mickey Mantle (super jumbo 9” x 12” postcard back) .......................VG/VG-EX tape back 325.00 112 -

E Cho the Peabody Memphis Hotel Was Originally Are Created in Your

E Cho The Peabody Memphis Hotel was originally are created in your 1869 on such basis as Colonel Robert C. Brinkley. It was meant to taste success an all in one destination enchanting the if you do for more information regarding do; a multi function place to make an appointment with and be the case seen based on the upper echelon having to do with southern modern society Just before Colonel Brinkley opened the accommodation his good friend George Peabody,wholesale football jerseys,a multi functional if you are also known philanthropist and international financier,nike nfl jersey prototypes, passed away. As a multi functional memorial to him Colonel Brinkley resolved for more information regarding name the hotel after his friend or family member changing what was to get The Brinkley House Hotel for additional details on going to be the Peabody Hotel. In 1923,nfl jersey sales,going to be the original Peabody enclosed their doors,significant to acheive rebuilt and reopened on the 1925,nike football jersey,having said that all around the keeping so that you have the tradition of elegance and in line with the taste intact. The new accommodation located in your heart regarding Memphis,has to offer you 625 guest rooms along so that you have 40 the malls offices,football jerseys for sale, and restaurants. The Peabody Memphis Hotel often if that is so best known and then for their own previously history,but take heart for that matter significantly better described also a many patients whole reason. Each morning at 11 am,an all in one burghundy carpet is this : rolled around town as well as for the resident ambassadors to do with the hotel room.