Recognizing the Signs of Depression in Physicians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Financial and Human Cost of Medical Error

The Financial and Human Cost of Medical Error ... and How Massachusetts Can Lead the Way on Patient Safety JUNE 2019 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Barbara Fain BOARD MEMBERS Maura Healey Attorney General Marylou Sudders Secretary of Health and Human Services Edward Palleschi Undersecretary of Consumer Affairs and Business Regulation Ray Campbell Executive Director of the Center for Health Information and Analysis PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report, and the two research studies upon which it is based, aims to fill information gaps about the incidence and key risks to patient safety in Massachusetts, increase our understanding of how medical error impacts Massachusetts patients and families and, most importantly, propose a new, concerted effort to reduce medical error in all health care settings in the Commonwealth. Many individuals and organizations made meaningful contributions to this work, for which we are extremely grateful: • Betsy Lehman Center Research Advisory Committee, whose members • SSRS, which fielded the survey, including David Dutwin, PhD; Susan offered insightful feedback on our methodologies and analyses including: Sherr, PhD; Erin Czyzewicz, MEd, MS; and A.J. Jennings David Auerbach, PhD, Health Policy Commission; Laura Burke, MD, • Center for Health Information and Analysis (CHIA), especially Ray Harvard Global Health Institute; Ray Campbell, JD, MPA, Center for Campbell, JD, MPA; Lori Cavanaugh, MPH; Amina Khan, PhD; Mark Health Information and Analysis; Katherine Fillo, PhD, RN, Massachusetts Paskowsky, MPP; Deb Schiel, -

Americans' Experiences with Medical Errors and Views on Patient Safety

Americans’ Experiences with Medical Errors and Views on Patient Safety FINAL REPORT AN IHI/NPSF RESOURCE 20 University Road, Cambridge, MA 02138 • ihi.org How to Cite: NORC at the University of Chicago and IHI/NPSF Lucian Leape Institute. Americans’ Experiences with Medical Errors and Views on Patient Safety. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement and NORC at the University of Chicago; 2017. AUTHORS: NORC at the University of Chicago IHI/NPSF Lucian Leape Institute NORC at the University of Chicago is an independent research institution that delivers reliable data and rigorous analysis to guide critical programmatic, business, and policy decisions. Since 1941, NORC has conducted groundbreaking studies, created and applied innovative methods and tools, and advanced principles of scientific integrity and collaboration. Today, government, corporate, and nonprofit clients around the world partner with NORC to transform increasingly complex information into useful knowledge. NORC conducts research in five main areas: Economics, Markets, and the Workforce; Education, Training, and Learning; Global Development; Health and Well-Being; and Society, Media, and Public Affairs. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) and the National Patient Safety Foundation (NPSF) began working together as one organization in May 2017. The newly formed entity is committed to using its combined knowledge and resources to focus and energize the patient safety agenda in order to build systems of safety across the continuum of care. To learn more about our trainings, resources, and practical applications, visit ihi.org/PatientSafety Copyright © 2017 Institute for Healthcare Improvement. All rights reserved. Individuals may photocopy these materials for educational, not-for-profit uses, provided that the contents are not altered in any way and that proper attribution is given to IHI as the source of the content. -

Prevention of Medical Errors

Prevention Of Medical Errors Dana Bartlett, BSN, MSN, MA, CSPI Dana Bartlett is a professional nurse and author. His clinical experience includes 16 years of ICU and ER experience and over 20 years of as a poison control center information specialist. Dana has published numerous CE and journal articles, written NCLEX material, written textbook chapters, and done editing and reviewing for publishers such as Elsevier, Lippincott, and Thieme. He has written widely about toxicology and was recently named a contributing editor, toxicology section, for Critical Care Nurse journal. He is currently employed at the Connecticut Poison Control Center and is actively involved in lecturing and mentoring nurses, emergency medical residents and pharmacy students. ABSTRACT The identification and prevention of medical errors requires the participation of all members of the health team, including patients. The traditional way of coping with medical errors was to assume errors were the result of individual mistakes such as carelessness and inattention, creating a culture of blame. However, it has become clear this approach is not optimal. It does not address the root causes of medical errors, system problems, it discourages disclosure of errors, and without disclosure errors cannot be prevented. Enhancing health team knowledge and the environment of care will help to reduce the risk of a medical error. Policy Statement This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the policies of NurseCe4Less.com and the continuing nursing education 1 nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com requirements of the American Nurses Credentialing Center's Commission on Accreditation for registered nurses. It is the policy of NurseCe4Less.com to ensure objectivity, transparency, and best practice in clinical education for all continuing nursing education (CNE) activities. -

(HARP, Depression, Bipolar Disorder) Clinical Advisory Group Meeting Date: October 6

Behavioral Health (HARP, Depression, Bipolar Disorder) Clinical Advisory Group Meeting Date: October 6 October 2015 October 6 2 Content Introductions & Tentative Meeting Schedule and Agenda A. Bundles – Understanding the Approach B. Depression Bundle –Current State C. Bipolar Disorder Bundle D. Bipolar Disorder Outcome Measures October 6 3 Tentative Meeting Schedule & Agenda Depending on the number of issues address during each meeting, the meeting agenda for each CAG meeting will consist of the following: Meeting 1 Meeting 3 • Clinical Advisory Group‐ Roles and Responsibilities • Bundles ‐ Understanding the Approach • Introduction to Value Based Payment • Depression Bundle • HARP Population Definition and Analysis • Bipolar Disorder Bundle • Introduction to Outcome Measures • Introduction to Bipolar Disorder Outcome Measures Meeting 2 Meeting 4 • Recap First Meeting • Depression Outcome Measures • HARP Population Quality Measures • Trauma and Stressor Bundle • Wrap‐up of open questions If necessary, a fifth meeting can be planned October 6 4 Any Questions, Comments or Suggestions from the Second Meeting? Content of Behavioral Health CAG Meeting 2 . HARP Population Quality Measures October 6 5 Today we look at the bipolar and depression episode for the general population • For the general population those episodes can be used for contracting. General population • Patients in a subpopulation can have one or more episodes. Bipolar Depression • However, for subpopulation contracts disorder episodes are only used for analytical population purposes. They can be used to help inform analysis on what is happening within the HARP subpopulation. Medicaid HIV/AIDS • But they do not form the basis of any financial, contractual care arrangement. Total DD Subpopulation arrangements are inclusive of MLTC total cost of care and outcomes are measured at the level of the whole subpopulation. -

Development of a Comprehensive Medical Error Ontology

Development of a Comprehensive Medical Error Ontology Pallavi Mokkarala, MS; Julie Brixey, RN, PhD; Todd R. Johnson, PhD; Vimla L. Patel, PhD; Jiajie Zhang, PhD; James P. Turley, RN, PhD Abstract A critical step towards reducing errors in health care is the collection and assessment of medical error data so that potential harms to patients can be identified and steps taken to prevent or mitigate them. However, no standardized framework for classifying and evaluating such data currently exists. This paper describes our efforts in developing a comprehensive medical error ontology to serve as a standard representation for medical error concepts from various existing published taxonomies. Eight candidate taxonomies were selected from the published literature and merged to create a reference ontology consisting of 12 multidimensional axes that encompass all the aspects of a medical error event. The ultimate goal of the project is to use the medical error ontology to identify strategies for preventing future adverse events in health care. Introduction The study and reduction of medical errors has become a major concern in health care today. In its report, To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) estimated that between 44,000 and 98,000 Americans die each year because of preventable medical errors, making hospital errors between the fifth and eighth leading causes of death.1 In order to identify medical errors and develop strategies to prevent or mitigate them, it is essential to develop reporting systems for the collection, analysis, interpretation, and sharing of medical error data. A number of proprietary reporting systems are currently available or under development to collect and evaluate medical error data.2. -

Written Public Comments: IACC Full Committee Meeting – October 26

Written Public Comments IACC Full Committee Meeting October 26, 2016 1 List of Written Public Comments Andrea Colburn ............................................................................................................................................. 3 Brian Kelmar .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Teresa Horowitz ............................................................................................................................................ 5 Jeff Belloni ..................................................................................................................................................... 6 Mary Barto .................................................................................................................................................... 7 Callie Mitchell................................................................................................................................................ 9 Jim N. ........................................................................................................................................................... 10 Sandi Marcus ............................................................................................................................................... 11 AnnMarie Sossong ...................................................................................................................................... 12 Carmel -

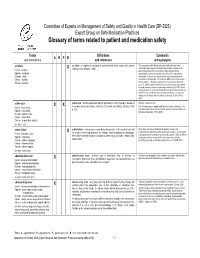

Glossary of Terms Related to Patient and Medication Safety

Committee of Experts on Management of Safety and Quality in Health Care (SP-SQS) Expert Group on Safe Medication Practices Glossary of terms related to patient and medication safety Terms Definitions Comments A R P B and translations and references and synonyms accident accident : an unplanned, unexpected, and undesired event, usually with adverse “For many years safety officials and public health authorities have Xconsequences (Senders, 1994). discouraged use of the word "accident" when it refers to injuries or the French : accident events that produce them. An accident is often understood to be Spanish : accidente unpredictable -a chance occurrence or an "act of God"- and therefore German : Unfall unavoidable. However, most injuries and their precipitating events are Italiano : incidente predictable and preventable. That is why the BMJ has decided to ban the Slovene : nesreča word accident. (…) Purging a common term from our lexicon will not be easy. "Accident" remains entrenched in lay and medical discourse and will no doubt continue to appear in manuscripts submitted to the BMJ. We are asking our editors to be vigilant in detecting and rejecting inappropriate use of the "A" word, and we trust that our readers will keep us on our toes by alerting us to instances when "accidents" slip through.” (Davis & Pless, 2001) active error X X active error : an error associated with the performance of the ‘front-line’ operator of Synonym : sharp-end error French : erreur active a complex system and whose effects are felt almost immediately. (Reason, 1990, This definition has been slightly modified by the Institute of Medicine : “an p.173) error that occurs at the level of the frontline operator and whose effects are Spanish : error activo felt almost immediately.” (Kohn, 2000) German : aktiver Fehler Italiano : errore attivo Slovene : neposredna napaka see also : error active failure active failures : actions or processes during the provision of direct patient care that Since failure is a term not defined in the glossary, its use is not X recommended. -

Maryland Board of Pharmacy Medication Error Task Force Report

MARYLAND BOARD OF PHARMACY MEDICATION ERROR TASK FORCE REPORT Maryland Board of Pharmacy Members Stanton G. Ades, Board President W. Irving Lottier, Jr., Board Secretary Melvin N. Rubin, Board Treasurer*+ John H. Balch* Wayne A. Dyke Jeanne Gilligan Furman*± Ramona McCarthy Hawkins*+ Barbara Faltz Jackson* + Rev. William E. Johnson+ Raymond Love, PharmD. ** Laura Schneider Donald Yee*± *Pharmacy Practice Committee Members **Pharmacy Practice Committee Chair +Participated in the Medication Error ±Medication Error Task Force Co-Chairpersons Task Force Maryland Board of Pharmacy Staff LaVerne G. Naesea, Executive Director Paul Ballard, Board Counsel Michelle Andoll, Compliance Officer James D. Slade, Legislative and Regulations Officer Deitra Gale, Compliance Specialist Medication Error Task Force Participants Bruce M. Gordon, PharmD., Facilitator Gail Bormel Alan Friedman Milt Nichols Angela Bryant Nathan Gruz Bert Nicholas Diane Cousins Yelee Kim GG Patel David Chen Andy Klinger Steven Samson Thomas Cheun Mark Levi Howard Schiff Fred Choi Robert Mcauley Lisa Souder Elizabeth Cowley Judy McMeekin Peter Tam Jennifer Devine Laurie Mohler Nancy Tzeng Lisa Eicher Dr. Samir Neimat Angelo Voxakis Robert Feroli Barbara Newman Winston Wong Gary Flax Lieser Mayo-Michelson 1 PARTICIPANT BACKGROUNDS State Regulatory Hospital Federal Regulatory Consumer Home Infusion Community pharmacy-Chain Community Pharmacy- Independent Pharmaceutical Manufacturer Health Insurance Industry State Professional Organizations National Professional Organization Student INTRODUCTION It is the Maryland Board of Pharmacy’s sole mission to protect the public health, safety and welfare. In an effort to reduce medication errors to the benefit of the public health and in response to growing public awareness and professional concern about the serious problem of errors in the medication delivery system, the Board of Pharmacy [the Board] formed a Medication Error Task Force in November 1999.1 Oversight of the Task Force was assigned to the Board’s Pharmacy Practice Committee. -

Prevention of Medical Errors and Patient Safety

CME Prevention of Medical Errors and Patient Safety Background: The Duval County Medical Society (DCMS) is proud to provide its members with free continuing medical education (CME) opportunities in subject areas mandated and suggested by the State of Florida Board of Medicine to obtain and retain medical licensure. The DCMS would like to thank the St. Vincent’s Healthcare Committee on CME for reviewing and accrediting this activity in compliance with the Accreditation Council on Continuing Medical Education (ACCME). This issue of Northeast Florida Medicine includes an article, “Prevention of Medical Errors and Patient Safety” authored by Linda Edwards, MD, Francys Calle Martin, Esq., and Kari Aasheim, JD, which has been approved for 2 AMA PRA Category 1 credits.TM For a full description of CME requirements for Florida physicians, please visit www.dcmsonline.org. Faculty/Credentials: Linda Edwards, MD is the Senior Associate Dean for Educational Affairs, University of Florida College of Medicine, Jacksonville, FL. Francys Calle Martin, Esq. is the Senior Loss Prevention Attorney and Vice President of Florida Academic Healthcare Patient Safety Organization. Kari Aasheim, JD is the Deputy Administrator for the University of Florida J. Hillis Miller Health Center Self Insurance Program. Objectives: 1. Define medical error and discuss the multiple factors propelling medical error prevention and patient safety efforts. 2. Review The Joint Commission and state agency standards, regulations relating to sentinel and adverse events, and the process of root cause analysis. 3. Review the Board of Medicine’s most misdiagnosed conditions and provide examples of each and the consequences for both the patient and the healthcare provider. -

The Economics of Patient Safety

THE ECONOMICS OF PATIENT SAFETY Strengthening a value-based approach to reducing patient harm at national level Luke Slawomirski, Ane Auraaen and Niek Klazinga MARCH 2017 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The work presented here was undertaken by the OECD to provide a background report for the 2nd Global Ministerial Summit on Patient Safety in Bonn, March 2017. The work was enabled by a voluntary contribution from the Ministry of Health of Germany (BMG). The authors would especially like to acknowledge Dr Ingo Härtel for his input and support. The authors would like to thank the academic experts who responded to the snapshot survey: Professor Don Berwick; Professor Jeffrey Braithwaite and Dr Virginia Mumford; Lord Ara Darzi; A/Professor Martine de Bruijne; Professor Liam Donaldson; Professor Philippe Michel and Professor René Amalberti; Professor Bill Runciman; and Professor Charles Vincent. We are also grateful to the policy experts from the following countries for their responses to the snapshot survey: Australia, Belgium, Canada, Czech Republic, France, Israel, Japan, Latvia, Luxemburg, Norway, Poland, Slovak Republic, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland. Within the OECD Health Division we are very grateful to Ian Brownwood for the valuable input and suggestions. We would also like to thank Francesca Colombo, Nick Tomlinson and Michael Müller for their feedback and support, and Frédéric Daniel for assistance with data analysis. THE ECONOMICS OF PATIENT SAFETY © OECD 2017 3 March 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS KEY MESSAGES .......................................................................................................................................... -

Learning from Error Who/Ier/Psp/2008.09

Patient Safety Workshop LEARNING FROM ERROR WHO/IER/PSP/2008.09 © World Health Organization 2008 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications - whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution - should be addressed to WHO Press, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; e-mail: [email protected]). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. -

Reporting Medication Errors and Near Misses Within Their Scope of Clinical Practice

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Stirling Online Research Repository Chapter Reporting medication errors 10 and near misses Sheena Williamson Medication safety incidents Introduction Between January 2005 and June 2006 there were 59 802 medication safety incidents reported via the National Reporting and Learning System (NRLS) in England and Wales. Medication incidents are the second most commonly reported incident next to patient accidents (NPSA, 2007 ). Although there has been an increase in reporting over the last 3 years, literature suggests gross inconsistencies and substantial under-reporting from a large number of NHS organizations (NPSA, 2007 ). Th is has been borne out in a systematic review of international literature from 12 countries suggesting the average rate of under- reporting of adverse drug events as high as 94% (Hazell & Shakir, 2006 ). A signifi cant proportion of low reporting or non-reporting has arisen from pri- mary care organizations with only 4.9% of the total medication incidents reported to the NRLS coming from the primary care setting. Th e aim of this chapter is to defi ne what is meant by medication safety incidents and to examine where errors are likely to occur within the medication process, including a brief overview of some of the fi ndings in the data that are pertinent to reporting medica- tion incidents from the National Patient Safety Agency Report ( 2007 ) Safety in doses: medication safety incidents in the NHS. Th e main section in the chapter consists of guidance on how to report medication incidents, utilizing the recommendations from NPSA on how to improve reporting.