Drama Games for Rehearsals Extract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

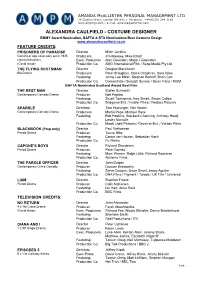

Alexandra Caulfield - Costume Designer

AMANDA McALLISTER PERSONAL MANAGEMENT LTD 74 Claxton Grove, London W6 8HE • Telephone: +44(0)207 244 1159 www.ampmgt.com • e-mail: [email protected] ALEXANDRA CAULFIELD - COSTUME DESIGNER EMMY Award Nomination, BAFTA & RTS Nominations Best Costume Design www.alexandracaulfield.co.uk FEATURE CREDITS: PRISONERS OF PARADISE Director Mitch Jenkins Coming of age Love story set in 1925 Producers Jim Mooney, Mike Elliott colonial Mauritius Exec. Producers Alan Govinden, Maria J Govinden (Covid shoot) Production Co. AMG International Film / Sega Media Pty Ltd THE FLYING SCOTSMAN Director Douglas Mackinnon Bio Drama Producers Peter Broughan, Claire Chapman, Sara Giles Featuring Jonny Lee Miller, Stephen Berkoff, Brian Cox Production Co. ContentFilm / Scottish Screen / Scion Films / MGM BAFTA Nominated Scotland Award Best Film THE BEST MAN Director Stefan Schwartz Contemporary Comedy Drama Producer Neil Peplow Featuring Stuart Townsend, Amy Smart, Simon Callow Production Co. Endgame Ent. / Insider Films / Redbus Pictures SPARKLE Directors Tom Hunsinger, Neil Hunter Contemporary Comedy Drama Producers Martin Pope, Michael Rose Featuring Bob Hoskins, Stockard Channing, Anthony Head, Lesley Manville Production Co. Magic Light Pictures / Revolver Ent. / Vertigo Films BLACKBOOK (Prep only) Director Paul Verhoeven Period Drama Producer Teune Hilte Featuring Carice van Houten, Sebastian Koch Production Co. Fu Works CAPONE’S BOYS Director Richard Standeven Period Drama Producer Peter Barnes Featuring Marc Warren, Ralph Little, Richard Rowntree Production Co. Alchemy Films THE PAROLE OFFICER Director John Duigan Contemporary Crime Comedy Producer Duncan Kenworthy Featuring Steve Coogan, Omar Sharif, Jenny Agutter Production Co. DNA Films / Figment / Toledo / UK Film / Universal LIAM Director Stephen Frears Period Drama Producer Colin McKeown Featuring Ian Hart, Anne Reid Production Co. -

Dryden on Shadwell's Theatre of Violence

James Blac k DRYDEN ON SHADWELL'S THEATRE OF VIOLENCE All admirers of J ohn Dryden can sympathise w ith H.T . Swedenberg's dream of o ne day "finding bundle after bundle of Dryden's manuscripts and a journal kept thro ugho ut his career. .. .! turn in the journal to the 1670's and eagerly scan the leaves to find out precisely when MacFlecknoe was written and what the ultimate occasion for it was. " 1 For the truth is that although MacFlecknoe can be provisionally dated 1678 the " ultimate occasion" of Dryden's satire on Thomas Shadwell has never been satisfactorily explained. We know that for abo ut nine years Dryden and Shadwell had been arguing in prologues and prefaces with reasonably good manners , chiefly over the principles of comedy. R.J. Smith makes a case for Shadwell's being considered the foremost among Dryden's many adversaries in literary argumentatio n, and points out that their discourse had reached the stage where Dryden, in A n Apology for Heroic Poetry ( 16 77), made "an appeal for a live-and-let-live agree ment." 2 T he generally serious and calm nature of their debate makes MacFlecknoe seem almost a shocking intrusion- a personally-or politically-inspired attack which shattered the calm of discourse. Surely-so the reasoning of commentators goes- there must have been a casus belli. It used to be thought that Dryden was reacting to an attack by Shadwell in The Medal of j ohn Bayes, but this theory has been discounted.3 A.S. Borgman, a Shadwell biographer, would like to be able to account for Dryden's "turning against" Shadwell and making him the butt of MacFlecknoe: Had he wearied of [Sh adwell's) rep eated boasts o f friendship w ith the wits? Had he become disgusted with (h is) arrogant treatment of those who did not applaud th e humours in The Virtuoso and A True Widow? Had he tired of DRYDEN ON SHADWELL'S THEATRE OF VIOLENCE 299 seeing Shadwell "wallow in the pit" and condemn plays? Or did some word or act bring to his mind the former controversy and the threat then made of condemning dulness?4 D.M. -

Restoration Comedy.Pdf

RESTORATION COMEDY (1660- 1700) For B.A. Honours Part- 1 Paper – 1 (Content compiled for Academic Purpose only from http://www.theatrehistory.com/ and other websites duly credited) Content compiled by- Dr. Amritendu Ghosal Assistant Professor Department of English Anugrah Memorial College Gaya. Email- [email protected] Topics Covered- 1. INTRODUCTION TO THE RESTORATION AGE 2. NATURE OF RESTORATION COMEDY 3. WOMEN PLAYWRIGHTS 4. APPEARANCE OF WOMEN ON THE ENGLISH STAGE 5. PERSISTENCE OF ELIZABETHAN PLAYS 6. PARODY OF HEROIC DRAMA 7. COLLIER'S ATTACK ON THE STAGE (Image from haikudeck.com) "THEN came the gallant protest of the Restoration, when Wycherley and his successors in drama commenced to write of contemporary life in much the spirit of modern musical comedy. A new style of comedy was improvised, which, for lack of a better term, we may agree to call the comedy of Gallantry, and which Etherege, Shadwell, and Davenant, and Crowne, and Wycherley, and divers others, laboured painstakingly to perfect. They probably exercised to the full reach of their powers when they hammered into grossness their too fine witticisms just smuggled out of France, mixed them with additional breaches of decorum, and divided the results into five acts. For Gallantry, it must be repeated, was yet in its crude youth. For Wycherley and his confreres were the first Englishmen to depict mankind as leading an existence with no moral outcome. It was their sorry distinction to be the first of English authors to present a world of unscrupulous persons who entertained no special prejudices, one way or the other, as touched ethical matters." -- JAMES BRANCH CABELL, Beyond Life. -

FRENCH INFLUENCES on ENGLISH RESTORATION THEATRE a Thesis

FRENCH INFLUENCES ON ENGLISH RESTORATION THEATRE A thesis submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University In partial fulfillment of A the requirements for the Degree 2oK A A Master of Arts * In Drama by Anne Melissa Potter San Francisco, California Spring 2016 Copyright by Anne Melissa Potter 2016 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read French Influences on English Restoration Theatre by Anne Melissa Potter, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree Master of Arts: Drama at San Francisco State University. Bruce Avery, Ph.D. < —•— Professor of Drama "'"-J FRENCH INFLUENCES ON RESTORATION THEATRE Anne Melissa Potter San Francisco, California 2016 This project will examine a small group of Restoration plays based on French sources. It will examine how and why the English plays differ from their French sources. This project will pay special attention to the role that women played in the development of the Restoration theatre both as playwrights and actresses. It will also examine to what extent French influences were instrumental in how women develop English drama. I certify that the abstract rrect representation of the content of this thesis PREFACE In this thesis all of the translations are my own and are located in the footnote preceding the reference. I have cited plays in the way that is most helpful as regards each play. In plays for which I have act, scene and line numbers I have cited them, using that information. For example: I.ii.241-244. -

James Griffiths Director

James Griffiths Director Television 2020 MIGHTY DUCKS Series director, executive producer Writer: Steven Brill, John Goldsmith, Cathy Yuspa Producer: Disney Plus TX TBC 2020 DELILAH Director (TV Movie) Writer: Aisling Bea, Kirker Butler, Sharon Horgan Producers: Kapital Ent. and Merman TX TBC 2019 STUMPTOWN Pilot director (picked up for series), executive producer Writer: Jason Richman Producer: Elias Gertler for ABC Studios Cast: Cobie Smulders TX 25 September 2019 A MILLION LITTLE THINGS Eps 11, 13, 15, 17, executive producer Writer: DJ Nash Producer: Aaron Kaplan, Dana Honor for ABC Studios TX 17 January 2019 2018 WRECKED Ep 310 The Island Family Creators: Jordan and Justin Shipley Producer: Jesse Hara and Ken Topolsky for TBS TX October 2018 A MILLION LITTLE THINGS Pilot, Ep 2, Ep 5, Ep 7, executive producer Writer: DJ Nash Producer: Aaron Kaplan, Dana Honor for ABC Studios TX 26 September 2018 WRECKED Ep 210 Nerd Speak Creators: Jordan and Justin Shipley Producer: Jesse Hara and Ken Topolsky for TBS TX 22 August 2018 2017 THE MAYOR Pilot and Eps 103, 104, 106 and 110, executive producer Writer: Jeremy Bronson EP: Jamie Tarses, Scott Stuber, Dylan Clark for ABC Studios Cast: Lea Michele, Brandon Micheal Hall TX 3 October 2017 BLACK-ISH Ep 323 Liberal Arts Writers: Larry Wilmore and Kenya Barris Cast: Anthony Anderson TX 3 May 2017 2016 CHARITY CASE Pilot, Writer: Robert Padnick Producer: Scott Printz for Twentieth Century Fox Cast: Courteney Cox Produced 2015 COOPER BARRETT’S GUIDE TO SURVIVING LIFE Pilot and series director, executive -

Mccready Dale Elena

McKinney Macartney Management Ltd DALE ELENA McCREADY NZCS - Director of Photography GRACE Director: John Alexander Producer: Kiaran Murray-Smith Starring: John Simm Tall Story Pictures / ITV TIN STAR (Series 3, Episodes 5 & 6) Director: Patrick Harkins Producer: Andy Morgan Starring: Tim Roth, Genevieve O’Reilly and Christina Hendricks Kudos Film and Television BELGRAVIA Director: John Alexander Producer: Colin Wratten Starring: Tamsin Greig, Philip Glenister and Alice Eve Carnival Film and Television BAGHDAD CENTRAL Director: Ben A. Williams Producer: Jonathan Curling Starring: Waleed Zuaiter, Corey Stoll and Bertie Carvel Euston Films TIN STAR (Series 2, Episodes 2, 5, 6 & 7) Directors: Gilles Bannier, Jim Loach and Chris Baugh. Producer: Liz Trubridge Starring: Tim Roth, Genevieve O’Reilly and Christina Hendricks Euston Films THE LAST KINGDOM (Series 3, Episodes 2 & 4) Director: Andy de Emmony Producers: Cáit Collins, Howard Ellis, Adam Goodman and Chrissy Skinns. Starring: Alexander Dreymon, Eliza Butterworth and Ian Hart. Carnival Film and Television THE SPLIT (Series 1) Director: Jessica Hobbs Producer: Lucy Dyke Starring: Nicola Walker, Stephen Mangan and Annabel Scholey. Sister Pictures Best TV Drama nomination – National Film Awards 2019 Gable House, 18 – 24 Turnham Green Terrace, London W4 1QP Tel: 020 8995 4747 E-mail: [email protected] www.mckinneymacartney.com VAT Reg. No: 685 1851 06 DALE ELENA McCREADY Contd ... 2 THE TUNNEL (Series 3, Episodes 1-2) Director: Anders Engstrom Producer: Toby Welch Starring: Clémence -

The English-Speaking Aristophanes and the Languages of Class Snobbery 1650-1914

Pre-print of Hall, E. in Aristophanes in Performance (Legenda 2005) The English-Speaking Aristophanes and the Languages of Class Snobbery 1650-1914 Edith Hall Introduction In previous chapters it has been seen that as early as the 1650s an Irishman could use Aristophanes to criticise English imperialism, while by the early 19th century the possibility was being explored in France of staging a topical adaptation of Aristophanes. In 1817, moreover, Eugene Scribe could base his vaudeville show Les Comices d’Athènes on Ecclesiazusae. Aristophanes became an important figure for German Romantics, including Hegel, after Friedrich von Schlegel had in 1794 published his fine essay on the aesthetic value of Greek comedy. There von Schlegel proposed that the Romantic ideals of Freedom and Joy (Freiheit, Freude) are integral to all art; since von Schlegel regarded comedy as containing them to the highest degree, for him it was the most democratic of all art forms. Aristophanic comedy made a fundamental contribution to his theory of a popular genre with emancipatory potential. One result of the philosophical interest in Aristophanes was that in the early decades of the 18th century, until the 1848 revolution, the German theatre itself felt the impact of the ancient comic writer: topical Lustspiele displayed interest in his plays, which provided a model for German poets longing for a political comedy, for example the remarkable satirical trilogy Napoleon by Friedrich Rückert (1815-18). This international context illuminates the experiences undergone by Aristophanic comedy in England, and what became known as Britain consequent upon the 1707 Act of Union. -

THE BIRTHDAY PARTY by Harold Pinter Directed by Ian Rickson

PRESS RELEASE – Tuesday 6th March 2018 IMAGES CAN BE DOWNLOADED HERE @BdayPartyLDN / TheBirthdayParty.London Sonia Friedman Productions in association with Rupert Gavin, Tulchin Bartner Productions, 1001 Nights Productions, Scott M. Delman present THE BIRTHDAY PARTY By Harold Pinter Directed by Ian Rickson CRITICALLY ACCLAIMED 60th ANNIVERSARY REVIVAL OF THE BIRTHDAY PARTY ENTERS FINAL WEEKS AT THE HAROLD PINTER THEATRE STRICTLY LIMITED WEST END RUN STARRING TOBY JONES, STEPHEN MANGAN, ZOË WANAMAKER AND PEARL MACKIE MUST COME TO AN END ON 14TH APRIL Audiences now have just five weeks left to see the critically acclaimed West End production of playwright Harold Pinter’s The Birthday Party. The company for the major revival, which runs 60 years since the play’s debut, includes Toby Jones, Stephen Mangan, Zoë Wanamaker, Pearl Mackie, Tom Vaughan-Lawlor and Peter Wight, and is directed by Ian Rickson. Stanley Webber (Toby Jones) is the only lodger at Meg (Zoë Wanamaker) and Petey Boles’ (Peter Wight) sleepy seaside boarding house. The unsettling arrival of enigmatic strangers Goldberg (Stephen Mangan) and McCann (Tom Vaughan-Lawlor) disrupts the humdrum lives of the inhabitants and their friend Lulu (Pearl Mackie), and mundanity soon becomes menace when a seemingly innocent birthday party turns into a disturbing nightmare. Truth and alliances hastily shift in Pinter's brilliantly mysterious dark-comic masterpiece about the absurd terrors of the everyday. The production is designed by the Quay Brothers, with lighting by Hugh Vanstone, music by Stephen Warbeck, sound by Simon Baker, and casting by Amy Ball. For more information visit TheBirthdayParty.London -ENDS- For further information please contact The Corner Shop PR on 020 7831 7657 Maisie Lawrence [email protected] / Ben Chamberlain [email protected] LISTINGS Sonia Friedman Productions in association with Rupert Gavin, Tulchin Bartner Productions, 1001 Nights Productions, Scott M. -

"Play Your Fan": Exploring Hand Props and Gender on the Restoration Stage Through the Country Wife, the Man of Mode, the Rover, and the Way of the World

Columbus State University CSU ePress Theses and Dissertations Student Publications 2011 "Play Your Fan": Exploring Hand Props and Gender on the Restoration Stage Through the Country Wife, the Man of Mode, the Rover, and the Way of the World Jarred Wiehe Columbus State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Wiehe, Jarred, ""Play Your Fan": Exploring Hand Props and Gender on the Restoration Stage Through the Country Wife, the Man of Mode, the Rover, and the Way of the World" (2011). Theses and Dissertations. 148. https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations/148 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at CSU ePress. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSU ePress. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://archive.org/details/playyourfanexploOOwieh "Play your fan": Exploring Hand Props and Gender on the Restoration Stage Through The Country Wife, The Man of Mode, The Rover, and The Way of the World By Jarred Wiehe A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of Requirements of the CSU Honors Program For Honors in the Degree of Bachelor of Arts In English Literature, College of Letters and Sciences, Columbus State University x Thesis Advisor Date % /Wn l ^ Committee Member Date Rsdftn / ^'7 CSU Honors Program Director C^&rihp A Xjjs,/y s z.-< r Date <F/^y<Y'£&/ Wiehe 1 'Play your fan': Exploring Hand Props and Gender on the Restoration Stage through The Country Wife, The Man ofMode, The Rover, and The Way of the World The full irony and wit of Restoration comedies relies not only on what characters communicate to each other, but also on what they communicate to the audience, both verbally and physically. -

Print This Article

JOURNAL OF ENGLISH STUDIES – VOLUME 17 (2019), 127-147. http://doi.org/10.18172/jes.3565 “DWINDLING DOWN TO FARCE”?: APHRA BEHN’S APPROACH TO FARCE IN THE LATE 1670S AND 80S JORGE FIGUEROA DORREGO1 Universidade de Vigo [email protected] ABSTRACT. In spite of her criticism against farce in the paratexts of The Emperor of the Moon (1687), Aphra Behn makes an extensive use of farcical elements not only in that play and The False Count (1681), which are actually described as farces in their title pages, but also in Sir Patient Fancy (1678), The Feign’d Curtizans (1679), and The Second Part of The Rover (1681). This article contends that Behn adapts French farce and Italian commedia dell’arte to the English Restoration stage mostly resorting to deception farce in order to trick old husbands or fathers, or else foolish, hypocritical coxcombs, and displaying an impressive, skilful use of disguise and impersonation. Behn also turns widely to physical comedy, which is described in detail in stage directions. She appropriates farce in an attempt to please the audience, but also in the service of her own interests as a Tory woman writer. Keywords: Aphra Behn, farce, commedia dell’arte, Restoration England, deception, physical comedy. 1 The author wishes to acknowledge funding for his research from the Spanish government (MINECO project ref. FFI2015-68376-P), the Junta de Andalucía (project ref. P11-HUM-7761) and the Xunta de Galicia (Rede de Lingua e Literatura Inglesa e Identidade III, ref. ED431D2017/17). 127 Journal of English Studies, vol. 17 (2019) 127-147 Jorge Figueroa DORREGO “DWINDLING DOWN TO FARCE”?: LA APROXIMACIÓN DE APHRA BEHN A LA FARSA EN LAS DÉCADAS DE 1670 Y 1680 RESUMEN. -

Drama Theatre Performance Ebook

DRAMA THEATRE PERFORMANCE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Simon Shepherd,Mick Wallis | 272 pages | 01 Nov 2004 | Taylor & Francis Ltd | 9780415234948 | English | London, United Kingdom Drama Theatre Performance PDF Book Five comic dramatists competed at the City Dionysia though during the Peloponnesian War this may have been reduced to three , each offering a single comedy. Our live performances are the ticket to a great evening spent in Downtown Hammond. The comedies of the golden s and s peak times are significantly different from each other. Southeastern Louisiana University Hammond, Louisiana 1. View all posts. It was patronized by the kings as well as village assemblies. Indian English Drama. Pandey, Sudhakar, and Freya Taraporewala, eds. The project may engage creative practice, but the thesis itself will be a critical, written work engaging the research and dramaturgy involved in the performance or artwork. Hence this is the only generation after Amanat and Agha Hashr who actually write for stage and not for libraries. English Moral Interludes. Theatre portal. The Application Deadline is March 10th for the first round of auditions; August 10th for the second round. Mime is a form of drama where the action of a story is told only through the movement of the body. Prof Hasan, Ghulam Jeelani, J. Toggle navigation Navigation Menu. Sanskrit Theatre in Performance. The First The First. Everyman , for example, includes such figures as Good Deeds, Knowledge and Strength, and this characterisation reinforces the conflict between good and evil for the audience. -

6 X 10.Long New.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-18865-4 - Gender, Theatre, and the Origins of Criticism: From Dryden to Manley Marcie Frank Index More information Index A Comparison Between the Two Stages, 91–93 criticism, 3, 4, 7, 134–135 A Lady’s New-Years Gift, 112 female genealogy of, 10, 93 Addison, Joseph, 1, 6, 10–12, 18, 60, 89, 96, genealogy of, 11, 137–138 102, 113, 137 historical orientation of, 1, 3, 4, 8, 21–22 and Trotter, 114 impartiality of, 12–13, 14, 16, 64, 81–83, 95, Agnew, Jean-Christophe, 5, 14, 95, 140 111, 113, 131, 134 Anderson, Benedict, 17 self-consciousness of, 112–114 Ariadne theatrical orientation of, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 11, She Ventures, and He Wins, 91 27–32, 43, 102, 125–127 Astell, Mary, 108 Crowne, John, 94–96, 157 Auerbach, Erich, 23, 97 Calisto, 94–96 authorship, female, 3, 10, 91–92, 100, 134–135, 136 Davenant, Sir William, 4, 68 Dennis, John, 58 Backscheider, Paula, 91, 100–101 drama, 1, 3, 91 Baldick, Chris, 137–138 affective tragedy, 73–74 Ballaster, Ros, 12, 113, 117, 129–131 comedies of manners, 55, 61 Barry, Elizabeth, 121, 124–125 French vs. English, 19, 28–30, 38–39 Behn, Aphra, 1–2, 4, 11, 12, 18, 105 heroic play, 4, 73, 121–123 and Dryden, 92, 96–98 masque, 95 See also Crowne, John Calisto criticism by, 93, 96–100 modern vs. ancient, 19, 30–31 Agnes de Castro, 104 rehearsal play, 2–3 Oroonoko, 91 The Critic, or A Tragedy Rehearsed, 3 preface to The Dutch Lover, 96–98 The Rehearsal, 2–3, 121 preface to The Lucky Chance, 96–100 The Rehearsal, or Bayes in Petticoats, 3 The Younger Brother, 91 The Two Queens