1 the 2020 General Election

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Decision of the Election Committee on a Due Impartiality Complaint Brought by the Respect Party in Relation to the London Deba

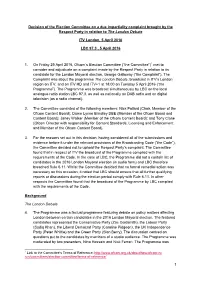

Decision of the Election Committee on a due impartiality complaint brought by the Respect Party in relation to The London Debate ITV London, 5 April 2016 LBC 97.3 , 5 April 2016 1. On Friday 29 April 2016, Ofcom’s Election Committee (“the Committee”)1 met to consider and adjudicate on a complaint made by the Respect Party in relation to its candidate for the London Mayoral election, George Galloway (“the Complaint”). The Complaint was about the programme The London Debate, broadcast in ITV’s London region on ITV, and on ITV HD and ITV+1 at 18:00 on Tuesday 5 April 2016 (“the Programme”). The Programme was broadcast simultaneously by LBC on the local analogue radio station LBC 97.3, as well as nationally on DAB radio and on digital television (as a radio channel). 2. The Committee consisted of the following members: Nick Pollard (Chair, Member of the Ofcom Content Board); Dame Lynne Brindley DBE (Member of the Ofcom Board and Content Board); Janey Walker (Member of the Ofcom Content Board); and Tony Close (Ofcom Director with responsibility for Content Standards, Licensing and Enforcement and Member of the Ofcom Content Board). 3. For the reasons set out in this decision, having considered all of the submissions and evidence before it under the relevant provisions of the Broadcasting Code (“the Code”), the Committee decided not to uphold the Respect Party’s complaint. The Committee found that in respect of ITV the broadcast of the Programme complied with the requirements of the Code. In the case of LBC, the Programme did not a contain list of candidates in the 2016 London Mayoral election (in audio form) and LBC therefore breached Rule 6.11. -

Brochure: Ireland's Meps 2019-2024 (EN) (Pdf 2341KB)

Clare Daly Deirdre Clune Luke Ming Flanagan Frances Fitzgerald Chris MacManus Seán Kelly Mick Wallace Colm Markey NON-ALIGNED Maria Walsh 27MEPs 40MEPs 18MEPs7 62MEPs 70MEPs5 76MEPs 14MEPs8 67MEPs 97MEPs Ciarán Cuffe Barry Andrews Grace O’Sullivan Billy Kelleher HHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH Printed in November 2020 in November Printed MIDLANDS-NORTH-WEST DUBLIN SOUTH Luke Ming Flanagan Chris MacManus Colm Markey Group of the European United Left - Group of the European United Left - Group of the European People’s Nordic Green Left Nordic Green Left Party (Christian Democrats) National party: Sinn Féin National party: Independent Nat ional party: Fine Gael COMMITTEES: COMMITTEES: COMMITTEES: • Budgetary Control • Agriculture and Rural Development • Agriculture and Rural Development • Agriculture and Rural Development • Economic and Monetary Affairs (substitute member) • Transport and Tourism Midlands - North - West West Midlands - North - • International Trade (substitute member) • Fisheries (substitute member) Barry Andrews Ciarán Cuffe Clare Daly Renew Europe Group Group of the Greens / Group of the European United Left - National party: Fianna Fáil European Free Alliance Nordic Green Left National party: Green Party National party: Independents Dublin COMMITTEES: COMMITTEES: COMMITTEES: for change • International Trade • Industry, Research and Energy • Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs • Development (substitute member) • Transport and Tourism • International Trade (substitute member) • Foreign Interference in all Democratic • -

{DOWNLOAD} Politics in Europe: an Introduction To

POLITICS IN EUROPE: AN INTRODUCTION TO POLITICS IN THE UNITED KINGDOM,FRANCE AND GERMANY 5TH EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK M Donald Hancock | 9781604266115 | | | | | Politics in Europe: An Introduction to Politics in the United Kingdom,France and Germany 5th edition PDF Book The public take part in Parliament in a way that is not the case at Westminster through Cross-Party Groups on policy topics which the interested public join and attend meetings of alongside Members of the Scottish Parliament MSPs. Regions of Asia. The radical feminists believe that these are rooted in the structures of family or domestic life. This group currently has 51 MPs. Parsons, T. Under this proposal, most MPs would be directly elected from constituencies by the alternative vote , with a number of additional members elected from "top-up lists. Sheriff courts deal with most civil and criminal cases including conducting criminal trials with a jury, known that as Sheriff solemn Court, or with a Sheriff and no jury, known as Sheriff summary Court. Sociologists usually apply the term to such conflicts only if they are initiated and conducted in accordance with socially recognized forms. The small Gallo-Roman population there became submerged among the German immigrants, and Latin ceased to be the language of everyday speech. Nevertheless, many radical feminists claim that a matriarchal society would be more peaceful compared to the patriarchal one. Powers reserved by Westminster are divided into "excepted matters", which it retains indefinitely, and "reserved matters", which may be transferred to the competence of the Northern Ireland Assembly at a future date. -

Civil Liberties 1/7 (1=Most Free, 7=Least Free)

Ireland | Freedom House Page 1 of 13 Freedom in the World 2018 Ireland Profile FREEDOM Freedom in the World STATUS: Scores Quick Facts FREE Freedom Rating 1/7 Political Rights 1/7 Civil Liberties 1/7 (1=Most Free, 7=Least Free) Aggregate Score: 96/100 (0=Least Free, 100=Most Free) Overview: Ireland is a stable democracy. Political rights and civil liberties are robust, although the government suffers from some incidence of corruption. There is some limited societal discrimination, especially against the traditionally nomadic Irish Travellers. Key Developments in 2017: https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2018/ireland 9/21/2018 Ireland | Freedom House Page 2 of 13 • Leo Varadkar—the son of an Indian immigrant, Dàil as the youngest Prime Minister (Taoiseach) ever, following the decision by Enda Kenny to step down after six years. • In July, the Council of Europe criticized the Irish government for failing to uphold its commitments to implementing anticorruption measures. • In March, the country was shocked by the discovery of a mass grave of babies and children at the site of the former Bon Secours Mother and Baby Home in Tuam, Galway. The facility had housed orphaned children and the children of unwed mothers, and closed in 1961. Political Rights and Civil Liberties: POLITICAL RIGHTS: 39 / 40 A. ELECTORAL PROCESS: 12 / 12 A1. Was the current head of government or other chief national authority elected through free and fair elections? 4 / 4 https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2018/ireland 9/21/2018 Ireland | Freedom House Page 3 of 13 president. Thus, the legitimacy of the prime minister is largely dependent on the conduct of Dàil elections, which historically have free and fair. -

IRLAND Minister of Further and Higher Education, Research, Innovation and Science Department of Further and Higher Education, Research, Innovation and Science

IRLAND Minister of Further and Higher Education, Research, Innovation and Science Department of Further and Higher Education, Research, Innovation and Science Simon HARRIS Born on 17. October 1986 in Greystones He was appointed as Minister of Further and Higher Education, Innovation and Science in June 2020. He is a native of County Wicklow and has been involved in the community all his life. He first became involved in politics through his work as a disability advocate. Before entering politics, Simon established the Wicklow Triple A Alliance, a charity to support children and families affected by Autism. He was first elected to Dáil Éireann in the 2011 General Election and was the youngest member of the 31st Dáil. During that Dail term, Simon served as a member of the Public Accounts Committee, Oireachtas Committee on Finance, Public Expenditure and Reform, Secretary of the Fine Gael Parliamentary Party and Co-Convenor of the Oireachtas Cross Party Group on Mental Health, before being appointed in July 2014 as Minister of State in the Departments of Finance, Public Expenditure and Reform and the Department of the Taoiseach with Special Responsibility for OPW, Public Procurement and International Banking (including IFSC). He was re-elected as TD for Wicklow and East Carlow in the February 2016 General Election and subsequently appointed Minister for Health. Prior to his election to Dáil Éireann, Simon was a member of both Wicklow County Council and Greystones Town Council, having been elected in the 2009 Local Elections with the highest percentage vote of any candidate in the country. He has also served his community as Chairperson of the County Wicklow Policing Committee, Chairperson of the Dublin-Mid Leinster Regional Health Forum, Board Member of Wicklow Tourism and Member of Wicklow Vocational Educational Committee. -

Scottish Parliament Election 2011 – Campaign Expenditure

Scottish Parliament election 2011 – campaign expenditure Contents Table 1: Summary of spending at the Scottish Parliament election 1 2011 Table 2: Total spend at the 2003, 2007 and 2011 Scottish 2 Parliament elections by party Chart 1: Total spend at the 2003, 2007 and 2011 Scottish 2 Parliament elections by party Table 3: Total spend at the Scottish Parliament election 2011 by 3 category Chart 2: Total spend at the Scottish Parliament election 2011 by 4 category Table 4: Total spend at the 2003, 2007 and 2011 Scottish 5 Parliament elections by party and category Chart 3: Total spend at the 2003, 2007 and 2011 Scottish 6 Parliament elections by category Chart 4: Total spend at the 2003, 2007 and 2011 Scottish 7 Parliament elections by party and category Glossary 8 Scottish Parliament election 2011 – campaign expenditure Table 1: Summary of spending at the Scottish Parliament election 2011 Regions Constituencies Spending Payments Notional Party name contested contested limit made expenditure Total All Scotland Pensioners Party 8 2 £664,000 £12,034 £0 £12,034 Angus Independents Representatives (AIR) 1 1 £92,000 £1,699 £0 £1,699 Ban Bankers Bonuses 2 0 £160,000 £4,254 £275 £4,529 British National Party 8 0 £640,000 £9,379 £400 £9,779 Christian Party "Proclaiming Christ's Lordship 8 2 £664,000 £352 £0 £352 Christian People's Alliance 2 0 £160,000 £988 £0 £988 Communist Party of Britain 0 1 £12,000 £0 £0 £0 Conservative and Unionist Party 8 73 £1,516,000 £256,610 £16,852 £273,462 Co-operative Party 0 11 £132,000 £1,865 £0 £1,865 Labour Party -

James Connolly and the Irish Labour Party

James Connolly and the Irish Labour Party Donal Mac Fhearraigh 100 years of celebration? to which White replied, `Put that furthest of all1' . White was joking but only just, 2012 marks the centenary of the founding and if Labour was regarded as conservative of the Irish Labour Party. Like most politi- at home it was it was even more so when cal parties in Ireland, Labour likes to trade compared with her sister parties. on its radical heritage by drawing a link to One historian described it as `the most Connolly. opportunistically conservative party in the On the history section of the Labour known world2.' It was not until the late Party's website it says, 1960s that the party professed an adher- ence to socialism, a word which had been `The Labour Party was completely taboo until that point. Ar- founded in 1912 in Clonmel, guably the least successful social demo- County Tipperary, by James cratic or Labour Party in Western Europe, Connolly, James Larkin and the Irish Labour Party has never held office William O'Brien as the polit- alone and has only been the minority party ical wing of the Irish Trade in coalition. Labour has continued this tra- Union Congress(ITUC). It dition in the current government with Fine is the oldest political party Gael. Far from being `the party of social- in Ireland and the only one ism' it has been the party of austerity. which pre-dates independence. The founders of the Labour The Labour Party got elected a year Party believed that for ordi- ago on promises of burning the bondhold- nary working people to shape ers and defending ordinary people against society they needed a political cutbacks. -

1. Debbie Abrahams, Labour Party, United Kingdom 2

1. Debbie Abrahams, Labour Party, United Kingdom 2. Malik Ben Achour, PS, Belgium 3. Tina Acketoft, Liberal Party, Sweden 4. Senator Fatima Ahallouch, PS, Belgium 5. Lord Nazir Ahmed, Non-affiliated, United Kingdom 6. Senator Alberto Airola, M5S, Italy 7. Hussein al-Taee, Social Democratic Party, Finland 8. Éric Alauzet, La République en Marche, France 9. Patricia Blanquer Alcaraz, Socialist Party, Spain 10. Lord John Alderdice, Liberal Democrats, United Kingdom 11. Felipe Jesús Sicilia Alférez, Socialist Party, Spain 12. Senator Alessandro Alfieri, PD, Italy 13. François Alfonsi, Greens/EFA, European Parliament (France) 14. Amira Mohamed Ali, Chairperson of the Parliamentary Group, Die Linke, Germany 15. Rushanara Ali, Labour Party, United Kingdom 16. Tahir Ali, Labour Party, United Kingdom 17. Mahir Alkaya, Spokesperson for Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation, Socialist Party, the Netherlands 18. Senator Josefina Bueno Alonso, Socialist Party, Spain 19. Lord David Alton of Liverpool, Crossbench, United Kingdom 20. Patxi López Álvarez, Socialist Party, Spain 21. Nacho Sánchez Amor, S&D, European Parliament (Spain) 22. Luise Amtsberg, Green Party, Germany 23. Senator Bert Anciaux, sp.a, Belgium 24. Rt Hon Michael Ancram, the Marquess of Lothian, Former Chairman of the Conservative Party, Conservative Party, United Kingdom 25. Karin Andersen, Socialist Left Party, Norway 26. Kirsten Normann Andersen, Socialist People’s Party (SF), Denmark 27. Theresa Berg Andersen, Socialist People’s Party (SF), Denmark 28. Rasmus Andresen, Greens/EFA, European Parliament (Germany) 29. Lord David Anderson of Ipswich QC, Crossbench, United Kingdom 30. Barry Andrews, Renew Europe, European Parliament (Ireland) 31. Chris Andrews, Sinn Féin, Ireland 32. Eric Andrieu, S&D, European Parliament (France) 33. -

ALAN KELLY TD DELIVERING for the PEOPLE of NENAGH Summer 2015

ALAN KELLY TD DELIVERING FOR THE PEOPLE OF NENAGH Summer 2015 Dear Constituent, I am honoured to serve the people of Nenagh along with Cllr Fiona Bonfield. I am delighted to take this opportunity to update you on some of the local matters that have arisen and show the progress that is being made in all areas for the benefit of the town as a whole. You will find here details of some of the work I have been doing and the funding that I have secured for the local area. As your public representative I am committed to working for all of Tipperary and ensuring that it is treated as a priority by the Government. I am very proud of all that I have delivered for Nenagh to date and that the town has changed for the better over the last four years. It is now very important for me to continue working for the area and my biggest aim is to continue promoting Nenagh as an attractive location for firms to start up or expand and in turn to boost job creation in the town. Please feel free to contact me or Cllr Bonfield at any time. ST. MARY’S MASTERCHEFS Congratulations to Mary’s Masterchefs from St Mary’s Secondary School, Nenagh – Aisling Sheedy, Sorcha Nagle , Jade Corcoran, Roisin Taplin and Niamh Dolan. They were the winners of the Senior Category in the Tipperary Student Enterprise Awards. This book was dedicated to the late Mr Brian McDermott. Brian was a fantastic person. It was always a pleasure to meet him and he was a very kind and funny person. -

Connections & Community

FOSTERING MEANINGFUL CONNECTIONS & COMMUNITY IN CHALLENGING TIMES VIRTUAL • INTERACTIVE • LIVE • ON DEMAND CONNACHT ULSTER LEINSTER MUNSTER IRELAND FINLAND BRITAIN AMERICA IGC NATIONAL CONFERENCE 2021 17th April 2021 • www.igc.ie Main Sponsor TU Dublin Table of CONTENTS Welcome & Thank you from the IGC President 3 Conference Programme 9 Workshop Sessions 11 IGC Conference Speakers 13 President’s Address & Reports 21 Infinite Possibilities at TU Dublin 46 A Guide to Accessing the IGC Virtual Conference 54 Exciting Times at IT Sligo 60 Sponsor Acknowledgment 65 List of Sponsors and Exhibitors 67 ATTENDING VIRTUAL CONFERENCE 1 Complete Pre Conference Log-in Check by Monday 12th April 2 Browse Conference Platform & Book Exhibitor Chats from 8am Monday 12th April 3 Attend Conference from 8am Saturday 17th April or on demand to Sunday 16th May. Full details on page 52 YOUR FUTURE IS I OURUR FOCUSUSS #choo#choose#cho elyit LLYYIT Runner-Up Institute TTeechnology of the YYeear 20211 (Sunday Times, Good University Guide) 9/10 of LYLYIT students have either 4,4,500+ returned to further study or Students gained employment within 4 months of graduation 2 50+ Campuses in Donegal CAO Programmes 37 72% Masters & Postgraduate of courses offer work programmes placement opportunities 15 CPDD part-time & 40+ postgradpgduate programmes Clubss & Societies on campus for Teachers & Educators 43% Affordable & Plentiful Student Accommodation increase in student enrolment in the last seven years ToTo book a schoo school visit, to arrange a campus tour or to findd out mmore about LYIT programmes annd CAO programme options contact: Fiona Kelly Letterkennyy Inst titute offT TeTechnology Schools EngagementEngagem Officeer E: fi[email protected] or [email protected] T: (074) 9186105 M: (086) 33809630963 LYIT_Stats Advert.indd 1 16/02/2021 12:52 WELCOME & THANK YOU Dear Conference Delegate, A warm welcome to you all to the 2021 IGC annual conference. -

Lettre Conjointe De 1.080 Parlementaires De 25 Pays Européens Aux Gouvernements Et Dirigeants Européens Contre L'annexion De La Cisjordanie Par Israël

Lettre conjointe de 1.080 parlementaires de 25 pays européens aux gouvernements et dirigeants européens contre l'annexion de la Cisjordanie par Israël 23 juin 2020 Nous, parlementaires de toute l'Europe engagés en faveur d'un ordre mondial fonde ́ sur le droit international, partageons de vives inquietudeś concernant le plan du president́ Trump pour le conflit israeló -palestinien et la perspective d'une annexion israélienne du territoire de la Cisjordanie. Nous sommes profondement́ preoccuṕ eś par le preć edent́ que cela creerait́ pour les relations internationales en geń eral.́ Depuis des decennies,́ l'Europe promeut une solution juste au conflit israeló -palestinien sous la forme d'une solution a ̀ deux Etats,́ conformement́ au droit international et aux resolutionś pertinentes du Conseil de securit́ e ́ des Nations unies. Malheureusement, le plan du president́ Trump s'ecarté des parametres̀ et des principes convenus au niveau international. Il favorise un controlê israelień permanent sur un territoire palestinien fragmente,́ laissant les Palestiniens sans souverainete ́ et donnant feu vert a ̀ Israel̈ pour annexer unilateralement́ des parties importantes de la Cisjordanie. Suivant la voie du plan Trump, la coalition israelienné recemment́ composeé stipule que le gouvernement peut aller de l'avant avec l'annexion des̀ le 1er juillet 2020. Cette decisioń sera fatale aux perspectives de paix israeló -palestinienne et remettra en question les normes les plus fondamentales qui guident les relations internationales, y compris la Charte des Nations unies. Nous sommes profondement́ preoccuṕ eś par l'impact de l'annexion sur la vie des Israelienś et des Palestiniens ainsi que par son potentiel destabilisateuŕ dans la regioń aux portes de notre continent. -

12.02.16 – 18.02.16 Welcome to Kaspress Ireland, Our Weekly Summary of Relevant and Interesting News from the Irish Press

KASPress Ireland 12.02.16 – 18.02.16 Welcome to KASPress Ireland, our weekly summary of relevant and interesting news from the Irish press. Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung London Office News Summary Email: [email protected] Politics . Taoiseach Enda Kenny will travel to Brussels later as EU leaders try to cut a deal with Britain to prevent a so-called "Brexit". Ireland could be allowed to limit welfare benefits to migrant workers from other European Union member states under a proposal under consideration by the European Commission last night ahead of a key EU summit on Britain’s membership of the bloc. There is growing anxiety in Fine Gael at the party’s failure to generate the momentum it had counted on going into the second half of the general election campaign. Taoiseach Enda Kenny has finally ruled out going into government with Fianna Fáil after the general election, raising the spectre of a hung Dáil. Latest Red C poll reveals a decline in support for Fine Gael and Sinn Féin, while support for Independents has grown. Ireland has been selected to co-chair a major United Nations summit of world leaders on refugees and migration later this year. The prospect of a Fine Gael/Fianna Fáil government moved a step closer after Taoiseach Enda Kenny repeatedly refused to rule out doing business with Micheál Martin. Taoiseach Enda Kenny and Fianna Fáil leader Micheal Martin will take the gloves off this week in an all-out battle to win the support of former Fianna Fáil voters who 'loaned' their vote to Fine Gael and Labour in the last election.