Retroverted Hip Pitcher Like Verlander)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baseball Rule” Faces an Interesting Test

The “Baseball Rule” Faces an Interesting Test One of the many beauties of baseball, affectionately known as “America’s pastime,” is the ability for people to come to the stadium and become ingrained in the action and get the chance to interact with their heroes. Going to a baseball game, as opposed to going to most other sporting events, truly gives a fan the opportunity to take part in the action. However, this can come at a steep price as foul balls enter the stands at alarming speeds and occasionally strike spectators. According to a recent study, approximately 1,750 people get hurt each year by batted 1 balls at Major League Baseball (MLB) games, which adds up to twice every three games. The 2015 MLB season featured many serious incidents that shed light on the issue of 2 spectator protection. This has led to heated debates among the media, fans, and even players and 3 managers as to what should be done to combat this issue. Currently, there is a pending class action lawsuit against Major League Baseball (“MLB”). The lawsuit claims that MLB has not 1 David Glovin, Baseball Caught Looking as Fouls Injure 1,750 Fans a Year, BLOOMBERG BUSINESS (Sept. 9, 2014, 4:05 PM), http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/20140909/baseballcaughtlookingasfoulsinjure1750fansayear. 2 On June 5, a woman attending a Boston Red Sox game was struck in the head by a broken bat that flew into the seats along the third baseline. See Woman hurt by bat at Red Sox game released from hospital, NEW YORK POST (June 12, 2015, 9:32 PM), http://nypost.com/2015/06/12/womanhurtbybatatredsoxgamereleasedfromhospital/. -

Download Preview

DETROIT TIGERS’ 4 GREATEST HITTERS Table of CONTENTS Contents Warm-Up, with a Side of Dedications ....................................................... 1 The Ty Cobb Birthplace Pilgrimage ......................................................... 9 1 Out of the Blocks—Into the Bleachers .............................................. 19 2 Quadruple Crown—Four’s Company, Five’s a Multitude ..................... 29 [Gates] Brown vs. Hot Dog .......................................................................................... 30 Prince Fielder Fields Macho Nacho ............................................................................. 30 Dangerfield Dangers .................................................................................................... 31 #1 Latino Hitters, Bar None ........................................................................................ 32 3 Hitting Prof Ted Williams, and the MACHO-METER ......................... 39 The MACHO-METER ..................................................................... 40 4 Miguel Cabrera, Knothole Kids, and the World’s Prettiest Girls ........... 47 Ty Cobb and the Presidential Passing Lane ................................................................. 49 The First Hammerin’ Hank—The Bronx’s Hank Greenberg ..................................... 50 Baseball and Heightism ............................................................................................... 53 One Amazing Baseball Record That Will Never Be Broken ...................................... -

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

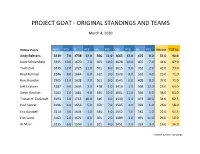

Project Goat - Original Standings and Teams

PROJECT GOAT - ORIGINAL STANDINGS AND TEAMS March 4, 2020 Hitting Points AVG PTS R PTS HR PTS RBI PTS SB PTS Hitting TOTAL Andy Behrens .3219 7.0 1738 12.0 566 11.0 1665 12.0 425 9.0 51.0 94.0 Dave Schoenfield .3295 10.0 1670 7.0 563 10.0 1628 10.0 407 7.0 44.0 87.0 Todd Zola .3339 12.0 1725 11.0 551 8.0 1615 9.0 352 2.0 42.0 73.0 Brad Kullman .3246 8.0 1664 6.0 512 3.0 1579 8.0 362 4.0 29.0 71.0 Ron Shandler .3305 11.0 1628 3.0 561 9.0 1545 6.0 408 8.0 37.0 71.0 Jeff Erickson .3287 9.0 1605 2.0 478 1.0 1410 1.0 508 12.0 25.0 63.0 Steve Gardner .3161 1.0 1681 9.0 596 12.0 1661 11.0 366 5.0 38.0 63.0 Tristan H. Cockcroft .3193 3.0 1713 10.0 546 6.0 1530 5.0 473 10.0 34.0 62.5 Paul Sporer .3196 4.0 1653 5.0 550 7.0 1505 4.0 392 6.0 26.0 58.0 Eric Karabell .3214 5.0 1644 4.0 543 5.0 1552 7.0 342 1.0 22.0 51.5 Eno Sarris .3163 2.0 1671 8.0 504 2.0 1489 3.0 491 11.0 26.0 50.0 AJ Mass .3215 6.0 1599 1.0 521 4.0 1451 2.0 353 3.0 16.0 36.0 *Sorted by final standings Pitching Points W PTS SV PTS K PTS ERA PTS WHIP PTS Pitching TOTAL Andy Behrens 187 11.5 0 1.5 2348 12.0 1.98 9.0 0.90 9.0 43.0 94.0 Dave Schoenfield 187 11.5 0 1.5 2288 11.0 1.95 11.0 0.91 8.0 43.0 87.0 Todd Zola 150 7.0 104 4.0 2154 8.0 2.03 7.0 0.95 5.0 31.0 73.0 Brad Kullman 141 4.5 141 10.5 1941 3.0 1.84 12.0 0.90 12.0 42.0 71.0 Ron Shandler 141 4.5 141 10.5 1886 2.0 1.97 10.0 0.93 7.0 34.0 71.0 Jeff Erickson 151 8.0 112 6.0 2130 6.0 2.01 8.0 0.90 10.0 38.0 63.0 Steve Gardner 147 6.0 105 5.0 2152 7.0 2.06 5.0 0.98 2.0 25.0 63.0 Tristan H. -

2021 Topps Dynamic Duals

Base Checklist 1 Ken Griffey Jr. Ronald Acuña Jr. 2 Kris Bryant Bryce Harper 3 Miguel Cabrera Casey Mize 4 John Smoltz Greg Maddux 5 Yadier Molina Buster Posey 6 Roger Clemens Pedro Martinez 7 Juan Soto Stephen Strasburg 8 Jose Abreu Frank Thomas 9 Corey Seager Cody Bellinger 10 Nolan Arenado Dylan Carlson 11 Trevor Bauer Shane Bieber 12 Matt Chapman Jose Canseco 13 Derek Jeter Mariano Rivera 14 Stan Musial Bob Gibson 15 Dwight Gooden Gary Carter 16 Alec Bohm Ke'Bryan Hayes 17 Xander Bogaerts Bobby Dalbec 18 Vladimir Guerrero Jr. Bo Bichette 19 Kyle Lewis Devin Williams 20 Freddie Freeman Cristian Pache 21 MIke Trout Jo Adell 22 Jacob deGrom Pete Alonso 23 Luis Garcia Nick Madrigal 24 Blake Snell Jake Cronenworth 25 Yordan Alvarez Randy Arozarena Autograph Checklist 1 Ken Griffey Jr. Ronald Acuña Jr. 2 Kris Bryant Bryce Harper 3 Miguel Cabrera Casey Mize 4 John Smoltz Greg Maddux 5 Yadier Molina Buster Posey 6 Roger Clemens Pedro Martinez 7 Juan Soto Stephen Strasburg 8 Jose Abreu Frank Thomas 9 Corey Seager Cody Bellinger 10 Nolan Arenado Dylan Carlson 11 Trevor Bauer Shane Bieber 12 Matt Chapman Jose Canseco 13 Derek Jeter Mariano Rivera 14 Stan Musial Bob Gibson 15 Dwight Gooden Gary Carter 16 Alec Bohm Ke'Bryan Hayes 17 Xander Bogaerts Bobby Dalbec 18 Vladimir Guerrero Jr. Bo Bichette 19 Kyle Lewis Devin Williams 20 Freddie Freeman Cristian Pache 21 MIke Trout Jo Adell 22 Jacob deGrom Pete Alonso 23 Luis Garcia Nick Madrigal 24 Blake Snell Jake Cronenworth 25 Yordan Alvarez Randy Arozarena Manager's Dream Insert MD-1 Mookie Betts Mike Trout MD-2 Fernando Tatis Jr. -

Tonight's Game Information

Thursday, April 1, 2021 Game #1 (0-0) T-Mobile Park SEATTLE MARINERS (0-0) vs. SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS (0-0) Home #1 (0-0) TONIGHT’S GAME INFORMATION Starting Pitchers: LHP Marco Gonzales (7-2, 3.10 in ‘20) vs. RHP Kevin Gausman (3-3, 3.62 in ‘20) 7:10 pm PT • Radio: 710 ESPN / Mariners.com • TV: ROOT SPORTS NW Day Date Opp. Time (PT) Mariners Pitcher Opposing Pitcher RADIO Friday April 2 vs. SF 7:10 pm LH Yusei Kikuchi (6-9, 5.12 in ‘20) vs. RH Johnny Cueto (2-3, 5.40 in ‘20) 710 ESPN Saturday April 3 vs. SF 6:10 pm RH Chris Flexen (8-4, 3.01 in ‘20 KBO) vs. RH Logan Webb (3-4, 5.47 in ‘20) 710 ESPN Sunday April 4 OFF DAY TONIGHT’S TILT…the Mariners open their 45th season against the San Francisco Giants at T-Mobile INSIDE THE NUMBERS Park…tonight is the first of a 3-game series vs. the Giants…following Saturday’s game, the Mariners will enjoy an off day before hosting the White Sox for a 3-game set beginning on Monday, April 5…tonight’s game will be televised live on ROOT SPORTS NW and broadcast live on 710 ESPN Seattle and the 2 Mariners Radio Network. With a win in tonight’s game, Marco Gonzales would join Randy Johnson ODDS AND ENDS…the Mariners open the season against San Francisco for the first time in club history with 2 wins on Opening Day, trailing ...also marks the first time in club history the Mariners open with an interleague opponent...the Mariners are only Félix Hernández (7) for the most 12-4 over their last 16 Opening Day contests...are 3-1 at home during that span. -

Detroit Tigers Clips Wednesday, May 27, 2015

Detroit Tigers Clips Wednesday, May 27, 2015 Detroit Free Press Detroit 1, Oakland 0: Price, pitching holds up for Tigers (Fenech) Tigers' Simon out today; Ryan to start if he makes it (Fenech) Verlander's simulated game a success; rehab start next? (Fenech) Detroit 1, Oakland 0: Why the Tigers won (Fenech) Hernan Perez looking to get more at-bats to end slump (Fenech) The Detroit News Price stifles A's as Tigers eke out a victory (Henning) 399: Kaline's last day short of history, long on regret (Henning) Tigers place Simon on bereavement leave (Henning) Verlander looks and feels fine in simulated game (Henning) Armed with new pitch, Farmer ready for '15 debut (Paul) Tigers lineup getting back in order (Henning) MLive.com Analysis: Alfredo Simon's sad circumstance puts Detroit Tigers in tough situation on West Coast trip (Schmehl) Detroit Tigers place Alfredo Simon on bereavement list, bring up Kyle Ryan from Triple-A Toledo (Schmehl) Tigers 1, A's 0: David Price, Detroit's bullpen combine for seven-hit shutout in Oakland (Schmehl) Miguel Cabrera leads AL first basemen in All-Star voting; Jose Iglesias ranks second among shortstops (Schmehl) Detroit Tigers' Justin Verlander sharp in simulated game, on track to begin rehab assignment early next week (Schmehl) Detroit Tigers' Justin Verlander sharp in simulated game, on track to begin rehab assignment early next week (Schmehl) MLB.com Price stopper: Lefty stymies A's, snaps Tigers' skid (Espinoza and Eymer) Price bears down, notches fourth win (Eymer) Double plays becoming Tigers' nemesis -

2021 Panini-Prizm Baseball Checklist

Card Set Number Player Team Seq. Base 1 Randy Arozarena Tampa Bay Rays Base 2 Ivan Rodriguez Texas Rangers Base 3 Kris Bryant Chicago Cubs Base 4 Tanner Houck Boston Red Sox Base 5 Justin Turner Los Angeles Dodgers Base 6 Deivi Garcia New York Yankees Base 7 Ronald Acuna Jr. Atlanta Braves Base 8 Luis Campusano San Diego Padres Base 9 Anderson Tejeda Texas Rangers Base 10 Craig Biggio Houston Astros Base 11 Alex Verdugo Boston Red Sox Base 12 Brailyn Marquez Chicago Cubs Base 13 Frank Thomas Chicago White Sox Base 14 Keegan Akin Baltimore Orioles Base 15 Isiah Kiner-Falefa Texas Rangers Base 16 Jose Ramirez Cleveland Indians Base 17 Victor Gonzalez Los Angeles Dodgers Base 18 Brandon Woodruff Milwaukee Brewers Base 19 Ken Griffey Jr. Seattle Mariners Base 20 Ryan Weathers San Diego Padres Base 21 Albert Pujols Los Angeles Angels Base 22 DJ LeMahieu New York Yankees Base 23 Trevor Story Colorado Rockies Base 24 Trea Turner Washington Nationals Base 25 Triston McKenzie Cleveland Indians Base 26 Jonathan India Cincinnati Reds Base 27 Jorge Guzman Miami Marlins Base 28 Anthony Rizzo Chicago Cubs Base 29 Taylor Trammell Seattle Mariners Base 30 Ryan Jeffers Minnesota Twins Base 31 Ramon Urias Baltimore Orioles Base 32 Max Scherzer Washington Nationals Base 33 Mike Yastrzemski San Francisco Giants Base 34 Jared Oliva Pittsburgh Pirates Base 35 Noah Syndergaard New York Mets Base 36 Justin Verlander Houston Astros Base 37 Blake Snell San Diego Padres Base 38 Austin Meadows Tampa Bay Rays Base 39 Carlos Correa Houston Astros Base 40 Jeff Bagwell Houston Astros Base 41 Ketel Marte Arizona Diamondbacks Base 42 Zach Plesac Cleveland Indians Base 43 Isaac Paredes Detroit Tigers Base 44 Jose Berrios Minnesota Twins Base 45 Garrett Crochet Chicago White Sox Base 46 Trevor Bauer Los Angeles Dodgers Base 47 Paul Goldschmidt St. -

Baseball: a U.S. Sport with a Spanish- American Stamp

ISSN 2373–874X (online) 017-01/2016EN Baseball: a U.S. Sport with a Spanish- American Stamp Orlando Alba 1 Topic: Spanish language and participation of Spanish-American players in Major League Baseball. Summary: The purpose of this paper is to highlight the importance of the Spanish language and the remarkable contribution to Major League Baseball by Spanish- American players. Keywords: baseball, sports, Major League Baseball, Spanish, Latinos Introduction The purpose of this paper is to highlight the remarkable contribution made to Major League Baseball (MLB) by players from Spanish America both in terms of © Clara González Tosat Hispanic Digital Newspapers in the United States Informes del Observatorio / Observatorio Reports. 016-12/2015EN ISSN: 2373-874X (online) doi: 10.15427/OR016-12/2015EN Instituto Cervantes at FAS - Harvard University © Instituto Cervantes at the Faculty of Arts and Sciences of Harvard University quantity and quality.1 The central idea is that the significant and valuable Spanish-American presence in the sports arena has a very positive impact on the collective psyche of the immigrant community to which these athletes belong. Moreover, this impact extends beyond the limited context of sport since, in addition to the obvious economic benefits for many families, it enhances the image of the Spanish-speaking community in the United States. At the level of language, contact allows English to influence Spanish, especially in the area of vocabulary, which Spanish assimilates and adapts according to its own peculiar structures. Baseball, which was invented in the United States during the first half of the nineteenth century, was introduced into Spanish America about thirty or forty years later. -

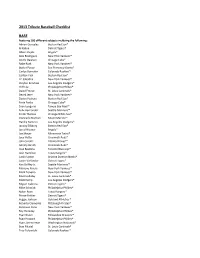

2013 Tribute Baseball Checklist BASE

2013 Tribute Baseball Checklist BASE Featurng 100 different subjects inclduing the following: Adrian Gonzalez Boston Red Sox® Al Kaline Detroit Tigers® Albert Pujols Angels® Alex Rodriguez New York Yankees® Andre Dawson Chicago Cubs® Babe Ruth New York Yankees® Buster Posey San Francisco Giants® Carlos Gonzalez Colorado Rockies™ Carlton Fisk Boston Red Sox® CC Sabathia New York Yankees® Clayton Kershaw Los Angeles Dodgers® Cliff Lee Philadelphia Phillies® David Freese St. Louis Cardinals® Derek Jeter New York Yankees® Dustin Pedroia Boston Red Sox® Ernie Banks Chicago Cubs® Evan Longoria Tampa Bay Rays™ Felix Hernandez Seattle Mariners™ Frank Thomas Chicago White Sox® Giancarlo Stanton Miami Marlins™ Hanley Ramirez Los Angeles Dodgers® Jacoby Ellsbury Boston Red Sox® Jered Weaver Angels® Joe Mauer Minnesota Twins® Joey Votto Cincinnati Reds® John Smoltz Atlanta Braves™ Johnny Bench Cincinnati Reds® Jose Bautista Toronto Blue Jays® Josh Hamilton Texas Rangers® Justin Upton Arizona Diamondbacks® Justin Verlander Detroit Tigers® Ken Griffey Jr. Seattle Mariners™ Mariano Rivera New York Yankees® Mark Teixeira New York Yankees® Matt Holliday St. Louis Cardinals® Matt Kemp Los Angeles Dodgers® Miguel Cabrera Detroit Tigers® Mike Schmidt Philadelphia Phillies® Nolan Ryan Texas Rangers® Prince Fielder Detroit Tigers® Reggie Jackson Oakland Athletics™ Roberto Clemente Pittsburgh Pirates® Robinson Cano New York Yankees® Roy Halladay Philadelphia Phillies® Ryan Braun Milwaukee Brewers™ Ryan Howard Philadelphia Phillies® Ryan Zimmerman Washington Nationals® Stan Musial St. Louis Cardinals® Troy Tulowitzki Colorado Rockies™ Willie Mays San Francisco Giants® AUTOGRAPHS On-Card Autographs At least 150 different cards including the following: Adam Jones Baltimore Orioles® Adrian Gonzalez Boston Red Sox® Albert Pujols Angels® Albert Belle Cleveland Indians® Andre Dawson Chicago Cubs® Andy Pettitte New York Yankees® Bob Gibson St. -

Weekly Notes 051718

MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL WEEKLY NOTES THURSDAY, MAY 17, 2018 CLUB 2,500 On Wednesday night against the Los Angeles Angels, Houston Astros starting pitcher Justin Verlander tossed his fi rst complete-game shutout of the 2018 season with seven strikeouts and fi ve hits allowed. With his ninth inning punchout against rookie sensation Shohei Ohtani, the six-time All-Star became the 33rd pitcher in Major League history to reach the 2,500-strikeout plateau. CC Sabathia of the New York Yankees, who has logged 2,874 strikeouts entering play today, is the only other active pitcher to reach the milestone. Following his excellent outing yesterday, in which he fi red 7.2 innings of shutout ball with three punchouts, Texas Rangers hurler Bartolo Colon is the next-closest pitcher to the 2,500-strikeout club. The 21-year-veteran will go into his next start with 2,486 punchouts for his career. Verlander recorded his historic strikeout in his 395th career outing, becoming just the sixth pitcher in history to reach the milestone in fewer than 400 career games. The 2011 AL MVP and Cy Young Award-winner joined Hall of Famers Nolan Ryan, Randy Johnson, Tom Seaver and Pedro Martínez, as well as Roger Clemens. Below is a table depicting each pitchers' cumulative stats at the time of their 2,500th career strikeout, sorted by fewest games needed: Pitcher Years IP G W-L H BB SO Randy Johnson 1988-99 2,108.0 313 152-83 1,625 991 2,500 Nolan Ryan 1966-78 2,286.1 338 143-134 1,559 1,480 2,500 Pedro Martinez 1992-2004 2,152.2 367 173-71 1,623 594 2,500 Roger Clemens 1984-96 2,695.0 373 186-109 2,297 868 2,500 Tom Seaver 1967-77 2,927.2 381 200-116 2,313 850 2,500 Justin Verlander 2005-18 2,613.2 395 193-116 2,277 812 2,500 Entering play today, three Astros pitchers pace the American League in ERA. -

BASE BASE CARDS 1 Tom Glavine Atlanta Braves™ 2 Randy Johnson

BASE BASE CARDS 1 Tom Glavine Atlanta Braves™ 2 Randy Johnson Arizona Diamondbacks® 3 Paul Goldschmidt St. Louis Cardinals® 4 Larry Doby Cleveland Indians® 5 Walker Buehler Los Angeles Dodgers® 6 John Smoltz Atlanta Braves™ 7 Tim Lincecum San Francisco Giants® 8 Jeff Bagwell Houston Astros® 9 Rhys Hoskins Philadelphia Phillies® 10 Rod Carew California Angels™ 11 Lou Gehrig New York Yankees® 12 George Springer Houston Astros® 13 Aaron Judge New York Yankees® 14 Aaron Nola Philadelphia Phillies® 15 Kris Bryant Chicago Cubs® 16 Bryce Harper Philadelphia Phillies® 17 Ken Griffey Jr. Seattle Mariners™ 18 George Brett Kansas City Royals® 19 Keston Hiura Milwaukee Brewers™ 20 Joe Mauer Minnesota Twins® 21 Ted Williams Boston Red Sox® 22 Eddie Mathews Milwaukee Braves™ 23 Jorge Soler Kansas City Royals® 24 Shohei Ohtani Angels® 25 Carl Yastrzemski Boston Red Sox® 26 Willie McCovey San Francisco Giants® 27 Joe Morgan Cincinnati Reds® 28 Juan Soto Washington Nationals® 29 Willie Mays San Francisco Giants® 30 Eloy Jimenez Chicago White Sox® 31 Babe Ruth New York Yankees® 32 Ichiro Seattle Mariners™ 33 Edgar Martinez Seattle Mariners™ 34 Pete Alonso New York Mets® 35 Rickey Henderson Oakland Athletics™ 36 Alex Bregman Houston Astros® 37 Mike Mussina Baltimore Orioles® 38 Miguel Cabrera Detroit Tigers® 39 Andy Pettitte New York Yankees® 40 Mariano Rivera New York Yankees® 41 David Ortiz Boston Red Sox® 42 Jackie Robinson Brooklyn Dodgers™ 43 Matt Chapman Oakland Athletics™ 44 Rafael Devers Boston Red Sox® 45 Yoan Moncada Chicago White Sox® 46 Pedro Martinez Montréal Expos™ 47 Freddie Freeman Atlanta Braves™ 48 Ketel Marte Arizona Diamondbacks® 49 Roger Clemens New York Yankees® 50 Vladimir Guerrero Jr.