Journal of the Southampton Local History Forum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ITEM NO: C2a APPENDIX 1

ITEM NO: C2a APPENDIX 1 Background Information Approximately 3600 flats and houses were built in Southampton in the five year period up to March 2006. About 80% of these were flats. Some 25% of these flats and houses were in the city centre, where the on-street parking facilities are available to everyone on a "Pay and Display" basis. Outside the central area, only about 10% of the city falls within residents' parking zones. So, out of the 3600 properties in all, it is estimated that only about 270 (or 7.5%) will have been within residents' parking zones and affected by the policy outlined in the report. Only in a few (probably less than 20) of these cases have difficulties come to light. In general, there is no question of anyone losing the right to a permit, although officers are currently seeking to resolve a situation at one particular development where permits have been issued in error. There are currently 13 schemes funded by the City Council and these cover the following areas:- Polygon Area Woolston North Woolston South Newtown/Nicholstown Bevois Town Freemantle Coxford (General Hospital) Shirley University Area (5 zones) These schemes operate from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. on weekdays and, in some cases, at other times as well. In addition, there are three further schemes at Bitterne Manor, Itchen and Northam that only operate during football matches or other major events at St Mary’s Stadium. These are funded by Southampton Football Club. Within all these schemes, parking bays are marked on the road for permit holders, often allowing short-stay parking by other users as well. -

Bitterne Park School Admissions Policy 2020-21

Southampton City Council Admission Policy for Bitterne Park School 2020/21 Southampton City Council is the admission authority for Bitterne Park School. As required in the School Admissions Code, the authority will consider all preferences at the same time for September 2020 admissions. Parents may express up to three (3) preferences, listing them in the order in which they would accept them. All preferences will be considered and where more than one school could be offered, the parents will be offered a place for their child at the higher ranked of the schools that could be offered. Children with Education, Health and Care Plans (EHCPs) that name a school Children with Education, Health and Care Plans (EHCPs) that name a school must be admitted to that school under the Education Act 1996 and with regard to the SEND Code of Practice. These children will be admitted to the named school, even if it is full, and are therefore outside the normal admission arrangements. As required by the Code these children will count as part of the Published Admission Number (PAN) for the school. Oversubscription criteria Applications submitted by 31 October 2019 will be dealt with first. If the number of applications submitted by 31 October 2019 for a school is greater than the PAN for the school, admissions will be decided according to the following priorities: 1. Children in public care (looked after children) and previously looked after children as defined in paragraph 1.7 of the School Admissions Code 2014. 2. Children subject to a child protection plan or deemed to be vulnerable by the Senior Officer with responsibility for safeguarding in Southampton City Council. -

BITTERNE AFTER the ROMANS. DOMESDAY Book Is Usually

148 : HAMPSHIRE FIELD CLUB BITTERNE AFTER THE ROMANS. By O. G. S". CRAWFORD, B.A., F.S.A. OMESDAY Book is usually regarded as a measure of antiquity, conferring the hall-mark of authentic age upon such places D as are there mentioned. Bitterne is not mentioned by this name in Domesday, but the history of the manor can be traced back to before Domesday. In the year 1045 King "Edward the Confessor gave land at Stanham to the monastery of St. Peter and Paul at Winchester, that is to say, to the Cathedral. The bounds of this land are given ; their identification is not at all easy, but one thing is quite certain, namely, that they include a portion- of South Stoneham ; for an earlier grant of land (in 932).to-the new Minster at Winchester can be identified by the bounds with part of North Stoneham. We must therefore exclude all the land included in that earlier grant from the present one (of 1045). We may also exclude all manors known to exist at the time of Domesday, for it is highly improbable that any such would be included in the grant of a manor made only 41 years previously. That cuts out the manors of Allington, Woolston, Shirley and Chilworth. Unfor- tunately the exact extent of these manors is unknown, but the possible extent of the Stoneham grant is to some extent defined. The bounds begin at Swaythlihg well, which must have been somewhere near Swaythling. The " old Itchen " and the " new river " (niwan ea) are then mentioned, and then, after a number of unidentifiable bound-marks (loam-pits, Wadda's stoc, white stone) we come to " wic hythe." This last must mean the hithe or quay of the old Saxon town of Southampton, whose alternative names were Homwic and Horn- or Ham-tun. -

Vicar Ascension Church, Bitterne Park Benefice in the Deanery of Southampton

Vicar Ascension Church, Bitterne Park Benefice In the deanery of Southampton Page 1 Index Title Page Welcome 3 Introduction 4 Our Vision 5 Our Church Life 6 Our Team 10 Our Organisation 12 The House 14 Role Description 15 Appendix 17 Page 2 Welcome Welcome to this parish profile and welcome to the Diocese of Winchester. At the heart of our life here is a desire to be always Living the Mission of Jesus. We are engaged in a strategic process to deliver a mission-shaped Diocese, in which parochial, pastoral, and new forms of pioneering and radical ministry all flourish. Infused with God’s missionary Spirit we want three-character traits to be clearly visible in how we live: ➢ Passionate personal spirituality ➢ Pioneering faith communities ➢ Prophetic global citizens The Diocese of Winchester is an exciting place to be now. We wait with eager anticipation to see how this process will unfold. We pray that, if God is calling you to join us in his mission in this part of the world, he will make his will abundantly clear to you. ‘As the Father sent me so I send you … Receive the Spirit.’ John 20:21 Tim Dakin Debbie Sellin Read more about Winchester Mission Action Planning. Bishop of Winchester Bishop of Southampton Page 3 Introduction Ascension is a growing church in Bitterne Park Parish and forms part of the Deanery of Southampton, with a lively Chapter of Clergy and Deanery Synod, and is in the Diocese of Winchester. Our parish is on the eastern side of Southampton, and covers four main areas, Bitterne Manor, Midanbury, Bitterne Park and part of Townhill Park. -

Southampton City Council

PUSH Strategic Flood Risk Assessment – 2016 Update Guidance Document: Southampton City Council Flood Risk Overview Sources of Flood Risk The city and unitary authority of Southampton is located in the west of the PUSH sub-region. It covers a total area of approximately 50 km². The city has 35 km of tidal frontage including the Itchen estuary, the tidal influence of which extends almost up to the administrative boundary of the city. Additionally there is 15 km of main river in Southampton. The Monks Brook stream joins the River Itchen at Swaythling and the Tanner’s Brook and Holly Brook streams flow through and combine in Shirley in the west of the city, passing under Southampton Docks before discharging into Southampton Water. At present, approximately 13% of Southampton’s land area is designated as within Flood Zones 2 and 3 (see SFRA Map: Flood Mapping Dataset). The SFRA has shown that the primary source of flood risk to Southampton is from the sea. The key parts of the city which are currently at risk of flooding from the sea are the Docks, the Itchen frontage on both sides of the Itchen Bridge, the Northam and Millbank areas, Bevois Valley, St Denys and the Bitterne Manor Frontage. The secondary source of flood risk to the city is from rivers and streams. The Monks Brook flood outline affects parts to the north of Swaythling and the Tanners Brook and Holly Brook flood outline affects parts of Lordswood, Lord’s Hill, Shirley and Millbrook. Southampton has also been susceptible to flooding from other sources including surface water flooding and infrastructure failure, previous incidents of which although have been isolated and localised, have occurred across the City and are often due to blockage of drains or gulleys. -

We're Keeping You Connected This Christmas

We’re keeping you connected this Christmas We will be operating a Special Timetable on Boxing Day on City Red services 1, 2, 3, 7 and 11: Thursday 26 December 2019 only. Southampton | Totton | Calmore via: West Quay, Central Station, Millbrook & Testwood Southampton, City Centre - - 0846 0918 0946 1015 1035 1055 then 15 Southampton Central Station - - 0852 0924 0952 1023 1043 1103 every 23 Totton, St Teresa’s Church - - 0903 0935 1003 1035 1055 1115 20 35 Calmore, Testwood Crescent 0807 0837 0907 0939 1008 1040 1100 1120 mins 40 Calmore, Bearslane Close 0809 0839 0909 0941 1011 1043 1103 1123 at: 43 Southampton, City Centre 35 55 1615 1635 1655 1725 Southampton Central Station 43 03 1623 1643 1703 1733 Totton, St Teresa’s Church 55 15 until 1635 1655 1715 1745 Calmore, Testwood Crescent 00 20 1640 1700 1720 1750 Calmore, Bearslane Close 03 23 1643 1703 1723 1753 Calmore, Bearslane Close 0810 0840 0910 0942 1012 1044 1104 1124 1144 then Calmore, Richmond Close 0813 0843 0913 0945 1016 1048 1108 1128 1148 every Calmore, Testwood Crescent 0817 0847 0917 0949 1020 1052 1112 1132 1152 Totton Shopping Centre 0823 0853 0923 0955 1027 1059 1119 1139 1159 20 mins Southampton Central Station 0835 0905 0935 1007 1040 1112 1132 1152 1212 at: Southampton, City Centre 0841 0911 0941 1014 1047 1119 1139 1159 1219 Calmore, Bearslane Close 04 24 44 1704 1724 1754white Calmore, Richmond Close 08 28 48 1708 1728 17580 / 100 / 100 / 0 (CMYK), 193 / 0 / 31 (RGB), #C1001F (HEX) Calmore, Testwood Crescent 12 32 52 1712 1732 1802 until Totton Shopping Centre 19 39 59 1719 1739 1808 Southampton Central Station 32 52 12 1732 1752 1820 Southampton, City Centre 39 59 19 1739 1759 1826 0 / 100 / 90 / 70 (CMYK), 87 / 20 / 24 (RGB), #571418 (HEX) 0 / 100 / 100 / 0 (CMYK), 193 / 0 / 31 (RGB), #C1001F (HEX) We’re keeping you connected this Christmas We will be operating a Special Timetable on Boxing Day on City Red services 1, 2, 3, 7 and 11: Thursday 26 December 2019 only. -

81, Bitterne Road West, Bitterne Manor, Southampton, Hampshire, SO18 1AN Guide Price £260,000

EPC D 81, Bitterne Road West, Bitterne Manor, Southampton, Hampshire, SO18 1AN Guide Price £260,000 Three Bedroom Detached Family Home Located in the popular of Bitterne Manor with easy access to both Southampton City Centre & Bitterne Village with it's wide range of amenities including supermarket, leisure centre, health centre & library. Bitterne train station is just a short walk away and there is a bus route for direct access to the city centre. The local primary school is rated Outstanding by Ofsted & is just a short walk away. THREE BEDROOM DETACHED FAMILY HOME WITH NO CHAIN!! This fantastic family home boasts a generous 13ft Lounge, 19ft open plan Kitchen/Dining Room with double doors leading to the rear garden, 13ft Master Bedroom, modern Kitchen & Bathroom. The property is double glazed & gas central heated. The rear garden is a great size with a lawned area, shingled area and hard standing area for additional parking. There is also a detached Garage. The front garden provides off road parking with double gates leading to the detached Garage. This property is being offered to the market with no forward chain. Viewing arrangement by appointment 023 8044 5800 [email protected] Morris Dibben, 377-379 Bitterne Road, Bitterne, SO18 5RR morrisdibben.co.uk Interested parties should satisfy themselves, by inspection or otherwise as to the accuracy of the description given and any floor plans shown in these property details. All measurements, distances and areas listed are approximate. Fixtures, fittings and other items are NOT included unless specified in these details. Please note that any services, heating systems, or appliances have not been tested and no warranty can be given or implied as to their working order. -

Southampton Forest Hills Driving Test Centre Routes

Southampton Forest Hills Driving Test Centre Routes To make driving tests more representative of real-life driving, the DVSA no longer publishes official test routes. However, you can find a number of recent routes used at the Southampton Forest Hills driving test centre in this document. While test routes from this centre are likely to be very similar to those below, you should treat this document as a rough guide only. Exact test routes are at the examiners’ discretion and are subject to change. Route Number 1 Road Direction Driving Test Centre Left Forest Hills Drive Mini roundabout right Woodmill Lane Mini roundabout ahead Woodmill Lane Traffic light left Portswood Rd Right Harefield Rd End of road left Woodcote Rd Left Harrison Rd End of road right Woodcote Rd End of road left Burgess Rd Right Tulip Rd End of road left Honeysuckle Rd Right Daisy Rd/Lobelia Rd End of road left Bassett Green Rd Roundabout left Bassett Avenue Roundabout ahead, 2nd traffic light left Highfield Avenue/Highfield Lane Mini roundabout ahead Highfield Lane Traffic light crossroads right Portswood Rd Traffic light ahead, traffic light left Slip Rd Left Thomas Lewis Way Traffic light ahead, traffic light right St Denys Rd/Cobden Bridge Traffic light left Manor Farm Rd Mini roundabout right Woodmill Lane Mini roundabout left Forest Hills Drive Right Driving Test Centre Route Number 2 Road Direction Driving Test Centre Right Forest Hills Drive/Meggeson Avenue End of road right Townhill Way Roundabout left West End Rd Right Hatley Rd/Taunton Drive Left Somerton -

Swan Quay, 25 Vespasian Road, Bitterne Manor

023 8023 3288 www.pearsons.com Swan Quay, 25 Vespasian Road, Bitterne Manor, Southampton, SO18 1DU 1 Bedroom - £139,950 Leasehold Pearsons Southern Ltd DESCRIPTION believe these An opportunity to purchase a top floor purpose built Riverside apartment with its own mooring and offering excellent water views over the River particulars to Itchen. The property is located on the east side of the city and was constructed in the mid 1990's. The property offers well planned be correct but accommodation and is presented in good decorative order throughout. As well as the property having its own mooring it also has direct access to the River Itchen from an attractive communal garden. In brief the accommodation comprises; entrance hall leading to lounge/diner which their accuracy cannot be measures 17' 4 x 14' 6 and also has access to a balcony which overlooks the River Itchen. Separate kitchen which measures 9' 2 x 6' 10, separate guaranteed bathroom and bedroom measuring 13' 1 x 12' 5. The property also benefits from a secure car park with double length allocated parking space. The and they do property is double glazed throughout and has gas central heating throughout and is being offered with no forward chain. Due to the rare not form part availability of this property and the direct River views we would highly recommend a viewing. of any contract. LOCATION Vespasian Road is located within the Bitterne Manor district to the east of Southampton. The city centre is a short distance away accessed via Northam Bridge and the A3024. Bitterne Manor has a rail station located on MacNaghten Road a short distance away. -

X10 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

X10 bus time schedule & line map X10 Bishop's Waltham View In Website Mode The X10 bus line (Bishop's Waltham) has 3 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Bishop's Waltham: 3:08 PM (2) Bishop's Waltham: 7:10 AM - 6:25 PM (3) Southampton City Centre: 6:25 AM - 5:38 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest X10 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next X10 bus arriving. Direction: Bishop's Waltham X10 bus Time Schedule 15 stops Bishop's Waltham Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 3:08 PM Technology College, Swanmore Tuesday 3:08 PM Recreation Ground, Swanmore Wednesday 3:08 PM St Barnabas Church, Swanmore Thursday 3:08 PM Church Road, Swanmore Civil Parish Friday 3:08 PM Hampton Hill, Swanmore Saturday Not Operational Moorlands Road, Swanmore Paradise Lane, Bishop's Waltham Rareridge Lane, Bishop's Waltham X10 bus Info Direction: Bishop's Waltham Gunners Park, Bishop's Waltham Stops: 15 Trip Duration: 14 min Hoe Road, Bishops Waltham Civil Parish Line Summary: Technology College, Swanmore, Hoe Road, Bishop's Waltham Recreation Ground, Swanmore, St Barnabas Church, Swanmore, Hampton Hill, Swanmore, Moorlands Road, Swanmore, Paradise Lane, Bishop's Waltham, Godfrey Pink Way, Bishop's Waltham Rareridge Lane, Bishop's Waltham, Gunners Park, Bishop's Waltham, Hoe Road, Bishop's Waltham, The Square, Bishop's Waltham Godfrey Pink Way, Bishop's Waltham, The Square, Saint George's Square, Bishops Waltham Civil Parish Bishop's Waltham, Priory Court, Bishop's Waltham, The Avenue, Bishop's -

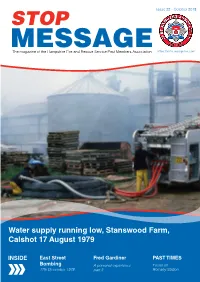

Stop Message Magazine Issue 22

Issue 22 - October 2018 STOP MESSAGE https://xhfrs.wordpress.com The magazine of the Hampshire Fire and Rescue Service Past Members Association Water supply running low, Stanswood Farm, Calshot 17 August 1979 INSIDE East Street Fred Gardiner PAST TIMES Bombing A personal experience Focus on 17th December 1978 part 3 Romsey Station World War 2 UK Propaganda Posters 1939 Keep Calm and Carry On 1939-45 What I Know - I Keep To Myself 1941 Lester Beall Careless Talk Costs Lives British propaganda during World War 2: Britain recreated the World War I Ministry of Information for the duration of World War II to generate propaganda to influence the population towards support for the war effort. A wide range of media was employed aimed at local and overseas audiences. Traditional forms of media such as newspapers and posters were joined by new media, including cinema (film), newsreels, and radio. A wide range of themes were addressed, fostering hostility to towards the enemy, support for the allies, and specific pro-war projects such as conserving metal, waste, and growing vegetables. Propaganda was deployed to encourage people to volunteer for onerous or dangerous war work, such as factories of in the Home Guard. Male conscription ensured that general recruitment posters were not needed, but specialist services posters did exist, and many posters aimed at women, such as the Land Army or the ATS. Posters were also targeted at increasing production. Pictures of the Armed Forces often called for support from civilians, and posters juxtaposed civilian workers and soldiers to urge that the forces were relying on them, and to instruct hem in the importance of their role. -

Bitterneparkschoolnews

BitterneParkSchoolNEWS www.bitterneparkschool.org.uk For available admission spaces at Bitterne Park School please contact us on 023 8029 4161 Summer 2019 NEWS EVENTS FUND RAISING COUNCIL SIXTH FORM Dear Parents/Guardians From the support staff: Mr Grove (Science); Ms Tate (Science) and Mr Rahman (ICT) It is that time of the year again, where we break for the summer holidays, another I would like to take this opportunity to year has passed by and I don’t know whether formally thank all the above members of it is a symptom of my age but it seems to staff for their contribution to the students of have gone even more quickly than the the school and wish them well in the future, previous year. wherever that may take them. Alternatively it could be explained by the Looking forward to next year – the school busy day to day activity within the school? will be admitting 394 new Year 7 students, Reading through this terms newsletter I am the Autistic Resource Base will be once more taken aback by the range and expanding and hopefully our numbers in volume of experiences/opportunities open to our very successful Sixth Form will continue students at the school. to rise. Our Teaching School will be training the largest group of new teachers Once more thousands of students have ever at 36 and the school site will begin the benefitted from our extra-curricular activities year complete. and trips which, form a central part of the Bitterne Park experience, additional to the On top of this the Riverside Federation traditional taught curriculum.