Samuel S. Murphy: Superintendent of the Mobile Public Schools from 1900-1926

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alabama Heralds 'Last Slave Ship' Discovery; Ponders Future by Kevin Mcgill, Associated Press on 04.15.19 Word Count 647 Level MAX

Alabama heralds 'last slave ship' discovery; ponders future By Kevin McGill, Associated Press on 04.15.19 Word Count 647 Level MAX Archaeological survey teams work to locate the remains of the slave ship Clotilda, in the delta waters north of Mobile Bay, Alabama. Photo by: Daniel Fiore/SEARCH, Inc. via AP MOBILE, Alabama — Dives into murky water, painstaking examinations of relics and technical data and rigorous peer review led historians and archaeologists to confirm last week that wreckage found in the Mobile River in 2018 was indeed the Clotilda, the last known ship to bring enslaved Africans to the United States. An event heralding the discovery on May 30 in the Mobile community of Africatown made clear that much work remains. The Alabama Historical Commission and others working on the project must decide how much can be salvaged, whether it can be brought ashore or if it should be left in place and protected. Perhaps more important: How can the interest and publicity engendered by the discovery of the Clotilda be harnessed to foster economic and racial justice in the community? Anderson Flen, a descendant of one of the Clotilda's enslaved, believes the historic find can spark new discussions on those topics. This article is available at 5 reading levels at https://newsela.com. "Number one is talking and communicating honestly and transparently," Flen said after a news conference on the effort to confirm the discovery. "The other thing is beginning to make some tangible things happen in this community." Another Clotilda survivor's descendant, Darron Patterson, said Africatown residents "have to come together as a group to make sure we're on one page, of one accord, to make sure this community survives." Thursday's gathering at a community center drew roughly 300 people. -

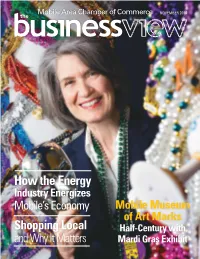

How the Energy

Mobile Area Chamber of Commerce NOVEMBER 2014 the How the Energy Industry Energizes Mobile’s Economy Mobile Museum of Art Marks Shopping Local Half-Century with and Why It Matters Mardi Gras Exhibit ADVANCED TECHNOLOGY IS: Fiber optic data that doesn’t slow you down C SPIRE BUSINESS SOLUTIONS CONNECTS YOUR BUSINESS. • Guaranteed speeds up to 100x faster than your current connection. • Synchronous transfer rates for sending and receiving data. • Reliable connections even during major weather events. CLOUD SERVICES Get Advanced Technology Now. Advanced Technology. Personal Service. 1.855.212.7271 | cspirebusiness.com 2 the business view NOVEMBER 2014 the Mobile Area Chamber of Commerce NOVEMBER 2014 | In this issue From the Publisher - Bill Sisson ON THE COVER Deborah Velders, director of the Mobile Museum Mobile Takes Bridge Message to D.C. of Art, gets in the spirit of Mardi Gras for the museum’s upcoming 50th anniversary celebration. Story on Recently, the Coastal Alabama as the Chamber’s “Build The I-10 page 10. Photo by Jeff Tesney Partnership (CAP) organized a Bridge Coalition,” as well as the regional coalition of elected officials work of CAP and many others. But from the Mobile Bay region to visit we’re still only at the beginning of Sens. Jeff Sessions and Richard the process. Now that the federal 4 News You Can Use Shelby, Cong. Bradley Byrne, and agencies have released the draft several congressmen from Alabama, Environmental Impact Study, 10 Mobile Museum of Art Celebrates Florida, Louisiana and Mississippi in public hearings have been held and 50 Years Washington, D.C. -

Dauphin Island Sea

Coastal Policy Center/ Mobile Bay National Estuary Program The Coastal Policy Center continues to be viable and integral part of the Dauphin Island Sea Lab Sea Lab’s support and service to the resource management agencies, Alabama’s Marine Research and Education Institution governments and the citizens of coastal Alabama. Efforts in the reporting year include: • Development of the Coastal Waterways Task Force to examine “carrying capacity” of waterways and waterfronts. • Hosting meetings among coastal planners from Alabama and Mississippi to discuss issues such as rapid growth affecting both coastal areas. • Smart Growth Initiatives, including participation in the tremendously successful “Smart Growth“Conference” in March. Over 300 attended this entire day conference in Mobile. The Mobile Bay National Estuary Program (MBNEP) directly obtained and brought in almost $1.2 million dollars in federal grant funds and local contributions targeted towards the study and solution of the environmental and natural resource challenges facing coastal Alabama and to implement a Dauphin Island Sea Lab Comprehensive Conservation 101 Bienville Boulevard and Management Plan (CCMP) Dauphin Island, AL for Mobile Bay and the Delta. 36528 Highlights include: Phone: 251-861-2141 Fax: 251-861-4646 • Alabama-Mississippi Rapid Website: www.disl.org Assessment Team to identify non-native aquatic species in Mobile Bay. A similar project is in planning for the Mississippi Coast in 2004. • The Oyster Gardening Program completed a third highly successful year and returned -

1Ba704, a NINETEENTH CENTURY SHIPWRECK SITE in the MOBILE RIVER BALDWIN and MOBILE COUNTIES, ALABAMA

ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS OF 1Ba704, A NINETEENTH CENTURY SHIPWRECK SITE IN THE MOBILE RIVER BALDWIN AND MOBILE COUNTIES, ALABAMA FINAL REPORT PREPARED FOR THE ALABAMA HISTORICAL COMMISSION, THE PEOPLE OF AFRICATOWN, NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC SOCIETY AND THE SLAVE WRECKS PROJECT PREPARED BY SEARCH INC. MAY 2019 ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS OF 1Ba704, A NINETEENTH CENTURY SHIPWRECK SITE IN THE MOBILE RIVER BALDWIN AND MOBILE COUNTIES, ALABAMA FINAL REPORT PREPARED FOR THE ALABAMA HISTORICAL COMMISSION 468 SOUTH PERRY STREET PO BOX 300900 MONTGOMERY, ALABAMA 36130 PREPARED BY ______________________________ JAMES P. DELGADO, PHD, RPA SEARCH PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR WITH CONTRIBUTIONS BY DEBORAH E. MARX, MA, RPA KYLE LENT, MA, RPA JOSEPH GRINNAN, MA, RPA ALEXANDER J. DECARO, MA, RPA SEARCH INC. WWW.SEARCHINC.COM MAY 2019 SEARCH May 2019 Archaeological Investigations of 1Ba704, A Nineteenth-Century Shipwreck Site in the Mobile River Final Report EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Between December 12 and 15, 2018, and on January 28, 2019, a SEARCH Inc. (SEARCH) team of archaeologists composed of Joseph Grinnan, MA, Kyle Lent, MA, Deborah Marx, MA, Alexander DeCaro, MA, and Raymond Tubby, MA, and directed by James P. Delgado, PhD, examined and documented 1Ba704, a submerged cultural resource in a section of the Mobile River, in Baldwin County, Alabama. The team conducted current investigation at the request of and under the supervision of Alabama Historical Commission (AHC); Alabama State Archaeologist, Stacye Hathorn of AHC monitored the project. This work builds upon two earlier field projects. The first, in March 2018, assessed the Twelvemile Wreck Site (1Ba694), and the second, in July 2018, was a comprehensive remote-sensing survey and subsequent diver investigations of the east channel of a portion the Mobile River (Delgado et al. -

Guide to the Clarence L. Hutchisson Jr. Papers

Guide to the Clarence L. Hutchisson Jr. Papers Descriptive Summary: Creator: Clarence L. Hutchisson Jr., 1902-1993 Title: Clarence L. Hutchisson Jr. Papers Dates: 1856-1956 (bulk 1927-1956) Quantity: 81.2 linear feet Abstract: Blueprints, correspondence, drawings, etching plates, news clippings, and a scrapbook related to the business dealings and genealogy of architect Clarence L. Hutchisson Jr. Accession: 10-09-267 ; 267-1993 Biographical Note: Clarence L. Hutchisson Jr., the last of the locally celebrated Hutchisson architects, was born in 1902 in Mobile, Alabama. From 1926 to 1932 Hutchisson worked in the office of his father, Clarence L. Hutchisson Sr. Between 1940 and 1945, Hutchisson trained as an engineer and would serve as chief architect for the Mobile Corps of Engineers. During his career, he designed a variety of structures in the Mobile area. Like his mother, Henrietta Homer Hutchisson, he was interested in the genealogy of the Homer family and he and his mother gathered information about several of his bloodlines. Much of this genealogical correspondence took place with his cousin Annie Homer Wilson and pertains to the Homer family in Nova Scotia, Canada. Hutchisson died in December 1993. Scope and Contents: This collection contains etching plates, news clippings, a scrapbook, and the business stamp of Clarence L. Hutchisson Jr. In addition, the collection is made up of a wide selection of correspondence, both business and private, contracts, building specifications, blueprints, and other related architectural documents. Of particular importance are the 200 architectural drawings of structures designed by the Hutchissons (ca. 1908-1972). These drawings are indexed by address as well as the client's name. -

GUIDE to MOBILE a Great Place to Live, Play Or Grow a Business

GUIDE TO MOBILE A great place to live, play or grow a business 1 Every day thousands of men and women come together to bring you the wonder © 2016 Alabama Power Company that is electricity, affordably and reliably, and with a belief that, in the right hands, this energy can do a whole lot more than make the lights come on. It can make an entire state shine. 2 P2 Alabama_BT Prototype_.indd 1 10/7/16 4:30 PM 2017 guide to mobile Mobile is a great place to live, play, raise a family and grow a business. Founded in 1702, this port city is one of America’s oldest. Known for its Southern hospitality, rich traditions and an enthusiastic spirit of fun and celebration, Mobile offers an unmatched quality of life. Our streets are lined with massive live oaks, colorful azaleas and historic neighborhoods. A vibrant downtown and quality healthcare and education are just some of the things that make our picturesque city great. Located at the mouth of the Mobile River at Mobile Bay, leading to the Gulf of Mexico, Mobile is only 30 minutes from the sandy white beaches of Dauphin Island, yet the mountains of northern Alabama are only a few hours away. Our diverse city offers an endless array of fun and enriching activities – from the Alabama Deep Sea Fishing Rodeo to freshwater fishing, baseball to football, museums to the modern IMAX Dome Theater, tee time on the course to tea time at a historic plantation home, world-renowned Bellingrath Gardens to the Battleship USS ALABAMA, Dauphin Island Sailboat Regatta to greyhound racing, Mardi Gras to the Christmas parade of boats along Dog River. -

Local Hotel Discounts Offered to USA Mitchell Cancer Institute Patients

Local Hotel Discounts Offered To USA Mitchell Cancer Institute Patients Candlewood Suites Downtown $45 – Rates should be made via Candlewood Suites Downtown is Ammenities: All suites include a Mobile e-mail: located in Mobile, close to full kitchen, with microwave, 121 N. Royal St. [email protected] Bienville Square, Gulf Coast dishwasher, two burner stovetop, Mobile, AL 36602 or call 251-690-7818 Exploreum, and Museum of coffeemaker and full size 1-888-287-8265 or Mobile. Nearby points of interest refrigerator. Complimentary 251-690-7818 also include National African parking. Outdoor courtyard and www.candlewood-mobile.com/ American Archives and Museum pool. 37 inch LCD televisions in all and Battleship Memorial Park. rooms. Complimentary high speed wireless internet. Pet-friendly. Courtyard by Marriott $85 – 1 King or Queen Beds Located on the Eastern Shore of All rooms offer a mini-refrigerator 13000 Cypress Way Alabama on Mobile Bay, this is the Spanish Fort, AL 36527 newest hotel in the area. Offering (251) 370-1161 Rates good through December 2013 spacious rooms and free high- (800) 228-9290 speed Internet, an indoor pool, No Shuttle Service whirlpool, fitness center, 10.89 Miles from MCI restaurant and 24 hour market. Fairfield Inn & Suites by Marriott $75 – 1 King or 2 Queen Beds This hotel offers suites with Start your morning off right with a 12000 Cypress Way $85 – King Suite separate living and sleeping areas, complimentary hot continental Spanish Fort, AL 36527 luxurious bedding, microwave, breakfast. Beginning in April 2013, (251) 370-1160 Rates good through December 2013 mini refrigerator, complimentary New breakfast enhancements will (800) 228-9290 internet and free local calls. -

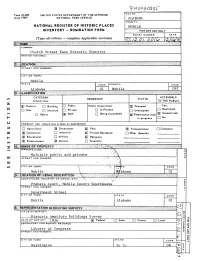

Iiiiii:Iilillll;Lli:|:Ili|:!: 01 COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY of DEEDS, ETC

STATE: Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE ALABAMA COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES MOBILE INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FORNPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER (Type all entries — complete applicable sections) Church Street East Historic District AND/OR HISTORIC: STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: Mobile COUNTY: Alabama 01 Mobile 097 ijiilliiiiiilliii CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSH.P STATUSCTAT..C (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC Z 6J3 District Q Building D Public Public Acquisition: S Occupied Yes: 0 ,, . , [~| Restricted D Site Q Structure D Private Q In Process Unoccupied ' — ' SI Unrestricted Q Object 53 Both Q Being Considered KiR-i PreservationD • worki ' — ' in progress u PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) f~) Agricultural 23 Government 0 Park Transportotion Q Comments (X) Commercial CD Industrial [£] Private Residence Other (Specify) h- (3 Educational CD Military 0 Religious [Xj Entertainment S Museum [~| Scientific OWNER'S NAME: Multiple public and private ULI STREET AND NUMBER: UJ CJTY OR TOWN: I abama Mobileiiiiii:iilillll;lli:|:ili|:!: 01 COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: . Probate Court, Mobile County ^Qurthou-s^e STREET AND NUMBER: Government Street Cl TY OR TOWN: STATE Mobile Alabama 01 TITLE OF SURVEY: Historic American Buildings Survey DATE OF SURVEY: 1936 lx] Federal State County Local 0 DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: Library of Congress C? STREET AND NUMBER: o CITY OR TOWN: Washington D. C, 08 (Check One) Excellent SI Good Q Fair Deteriorated [ I Ruins i~~l Unexposed CONDITION (Check One) (Check One) Altered Q Unaltered Moved [XJ Original Site DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (if known) PHYSICAL. -

The Impact of the 1973 Flooding of the Mobile River System on The

Northeast Gulf Science Volume 1 Article 3 Number 2 Number 2 12-1977 The mpI act of the 1973 Flooding of the Mobile River System on the Hydrography of Mobile Bay and East Mississippi Sound William W. Schroeder University of Alabama DOI: 10.18785/negs.0102.03 Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/goms Recommended Citation Schroeder, W. W. 1977. The mpI act of the 1973 Flooding of the Mobile River System on the Hydrography of Mobile Bay and East Mississippi Sound. Northeast Gulf Science 1 (2). Retrieved from https://aquila.usm.edu/goms/vol1/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Gulf of Mexico Science by an authorized editor of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Schroeder: The Impact of the 1973 Flooding of the Mobile River System on the Northeast Gulf Science Vol. 1, No.2. p. 68-76 December 1977 THE IMPACT OF THE 1973 FLOODING OF THE MOBILE RIVER SYSTEM ON THE HYDROGRAPHY OF MOBILE BAY AND EAST MISSISSIPPI SOUND 1 by William W. Schroeder Associate Professor of Marine Science University of Alabama P. 0. Box386, Dauphin Island, AL36582 ABSTRACT: Hydrographic conditions in lower Mobile Bay and East Mississippi Sound are docu mented during two flooding intervals of the Mobile River System. The flooding river waters so dominated Mobile Bay that a near limnetic system prevailed for over 30 days except in the deeper areas. East Mississippi Sound was also greatly influenced by river waters, but to a lesser extent than Mobile Bay. -

Tourism a LOOK BACK & FORWARD

Tourism A LOOK BACK & FORWARD Visit Mobile is proud to share with you, our stakeholders and friends, a review of the major initiatives the organization undertook in 2020 and the top goals for 2021. You will see our focus utilizing a balanced approach to tourism in order to shorten the COVID recovery to our destination. FOOD SERVICE PRACTICING COVID SAFETY AT SQUID INK 2020 A LOOK BACK The Lodging Room Tax for the 2019/2020 fiscal Since the discovery of the year was off to a record start until the COVID-19 remains of the scuttled pandemic shattered the industry by halting schooner, Clotilda, Mobile consumer travel in March 2020 and devastating has been on the cusp of Mobile’s travel and hospitality community; as well being a leading destination as North America’s. of Cultural / Heritage Tourism in the southeast, U.S., In May of 2020, the Tourism Improvement District and world. As the year unfolded, Visit Mobile lead (TID) became a law for the City of Mobile; the first the collaboration of developing Africatown Tourism city in the state of Alabama alongside local community leaders (turning the to have a TID. The story of the community into an experience), as the governing organization, City of Mobile awarded a performance contract Mobile Area Lodging with the Savannah College of Art & Design (SCAD) Corporation (MALC), to develop an Immersive Experience in Africatown subsequently formed a and Documentary Film of the Clotilda Journey. Board of Directors and began collecting assessments the following July In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, Carnival on room nights within the city limits. -

For More Information

MEMORANDUM FOR Active Duty, Reserve, National Guard JAG Officers, and Civilian Attorneys SUBJECT: 29th Annual Alabama Military Law Symposium – August 10-11, 2018 – at Battle House Renaissance Hotel, Mobile, Alabama The Military Law Committee of the Alabama State Bar invites you and any of your fellow attorneys/paralegals to attend the 29th Annual Alabama Military Law Symposium. This year’s symposium will be held at the Battle House Renaissance Hotel located at 26 North Royal Street, in Mobile, Alabama, Friday, August 10 and Saturday, August 11. Registration will start at 11:00 a.m. on Friday and continue thru to the end of the symposium on Saturday. The uniform for all instructional sessions will be the Army Combat Uniform (ACU) in either the Universal Camouflage Pattern (UCP) or Operational Camouflage Pattern (OCP); Airman Battle Uniform (ABU); or service equivalent. Civilian attire is professional business casual attire. Casual attire may be worn for social events but should be professional in appearance. We have a great list of speakers this year. The training provides an opportunity for an interactive exchange of information and ideas on a wide range of current legal topics unique to the practice of law. This year’s presentations will focus on the areas of Administrative Law, Criminal Law, Ethics/Professional Conduct, Geopolitical Issues, Military Justice, Historical Issues, and Regulatory Updates. The majority of this instruction will qualify for mandatory Continuing Legal Education (CLE) credit with most State Bars. In fact, the State of Alabama’s Bar Association is working to approve this course for up to a total of 8 hours of CLE credit which includes 1 hour of ethics. -

Liiilllllltllt^^ COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY of DEEDS

P/-/QQ /0073 STATE: Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE ALABAMA COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES MOBILE INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FORNPS USE ONLY *r^~~ ——— 1 ——— ~~~--^ ENTRY NUMBER ' DATE (lype all entries — complete app//cafi/^secfigjjsyj^/ TX N SEP 2 '< «Z COMMON: /V ^ '<QjJ; '% BRAGG - MITCHELl. HOUSE fat U/* ^ %ti AND/OR HISTORIC: 1 __ J At ^ /V> JUDGE JOHN BRAGG HOME Q, $£?/n« * 3 ill STREET AND NUMBER: \'Cr» SV /^ **/ 1906 Springhfll Avenue ^Y^TTTt^'^ CITY OR TOWN: ^^L__L_^-^^ Mobile STATE CODE COUNTY: CODE Alabama 01 Mobile 097 STATUS ACCESSIBLE IS* CATEGORY OWNERSH.P (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC Z (~~| District (SXBuilding f~l Public Public Acquisition: D Occupied Y«s: O tra 1 1 . j R/l/ Restricted G Site Q Structure 1^ Private Q '« Process .Ofl Unoccupied !/Wv i — ... n Unrestricted (~] Object 1 I Both R/V Being Considered (_J Preservation work 1- in progress ' —' ^° u PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) z> Q Agricultural ( | Government | | Park Q Transportation 1 1 Comments t* Q Commercial CD Industrial Q Private Residence |"v| Other (Specify) h- Q Educational CD Mi itary Q Religious Q Entertainment l~~) Museum [~1 Scientific None co ................. sssss:;*;*^^ z ;•;::::•;;;:;•;:;•;• !;-^ OWNER'S NAME: Ul A. S. Mttchell Foundation > tr UJ STREET AND NUMBER: UJ First National Bank Building CO CITY OR TOWN: STA TE: CODE Mobile Alabama oi liiilllllltllt^^ COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS. ETC: Mobile County Courthouse COUNTY: STREET AND NUMBER: Government Street CITY OR TOWN: STA TE CODE Mobile Alabama 01 , ^i^^^^SKiilWBBSM^fciiiii^^illllllii /> TITLE OF SURVEY: •n ENTR Tl H.A.B.S.