Schizoaffective Disorder Which Symptoms Should

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Negative Symptoms in Schizophrenia

Reward Processing Mechanisms of Negative Symptoms in Schizophrenia Gregory P. Strauss, Ph.D. Assistant Professor Department of Psychology University of Georgia Disclosures ACKNOWLEDGMENTS & DISCLOSURES ▪ Receive royalties and consultation fees from ProPhase LLC in connection with commercial use of the BNSS and other professional activities; these fees are donated to the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation. ▪ Last 12 Months: Speaking/consultation with Minerva, Lundbeck, Acadia What are negative symptoms and why are they important? Domains of psychopathology in schizophrenia Negative Symptoms ▪ Negative symptoms - reductions in goal-directed activity, social behavior, pleasure, and the outward expression of emotion or speech Cognitive Positive ▪ Long considered a core feature of psychotic disorders1,2 Deficits Symptoms ▪ Distinct from other domains of psychopathology (e.g., psychosis, disorganization) 3 ▪ Associated with a range of poor clinical outcomes (e.g., Disorganized Affective disease liability, quality of life, subjective well-being, Symptoms Symptoms recovery) 4-7 1. Bleuler E. [Dementia praecox or the group of schizophrenias]. Vertex Sep-Oct 2010;21(93):394-400. 2. Kraepelin E. Dementia praecox and paraphrenia (R. M. Barclay, Trans.). New York, NY: Krieger. 1919. 3. Peralta V, Cuesta MJ. How many and which are the psychopathological dimensions in schizophrenia? Issues influencing their ascertainment. Schizophrenia research Apr 30 2001;49(3):269-285. 4. Fervaha G, Remington G. Validation of an abbreviated quality of life scale for schizophrenia. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol Sep 2013;23(9):1072-1077. 5. Piskulic D, Addington J, Cadenhead KS, et al. Negative symptoms in individuals at clinical high risk of psychosis. Psychiatry research Apr 30 2012;196(2-3):220-224. -

Neurophysiological Correlates of Avolition-Apathy in Schizophrenia: a Resting-EEG Microstates Study T ⁎ Giulia M

NeuroImage: Clinical 20 (2018) 627–636 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect NeuroImage: Clinical journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ynicl Neurophysiological correlates of Avolition-apathy in schizophrenia: A resting-EEG microstates study T ⁎ Giulia M. Giordanoa,1, Thomas Koenigb,1, Armida Muccia, , Annarita Vignapianoa, Antonella Amodioa, Giorgio Di Lorenzoc, Alberto Siracusanoc, Antonello Bellomod, Mario Altamurad, Palmiero Monteleonee, Maurizio Pompilif, Silvana Galderisia, Mario Maja, The add-on EEG study of the Italian Network for Research on Psychoses2 a Department of Psychiatry, University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli”, Naples, Italy b Translational Research Center, University Hospital of Psychiatry, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland c Department of Systems Medicine, University of Rome “Tor Vergata”, Rome, Italy d Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, Psychiatry Unit, University of Foggia, Foggia, Italy e Department of Medicine, Surgery and Dentistry “Scuola Medica Salernitana”, Section of Neurosciences, University of Salerno, Salerno, Italy f Department of Neurosciences, Mental Health and Sensory Organs, Suicide Prevention Center, Sant' Andrea Hospital, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Background: The “Avolition-apathy” domain of the negative symptoms was found to include different symptoms Schizophrenia by factor analytic studies on ratings derived by different scales. In particular, the relationship of anhedonia with Avolition-apathy this domain is controversial. Recently introduced negative symptom rating scales provide a better assessment of Anhedonia anhedonia, allowing the distinction of anticipatory and consummatory aspects, which might be related to dif- Resting-EEG ferent psychopathological dimensions. The study of associations with external validators, such as electro- Brain electrical microstates physiological, brain imaging or cognitive indices, might shed further light on the status of anhedonia within the Avolition-apathy domain. -

Sex Differences in Symptom Presentation of Schizotypal

Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine DigitalCommons@PCOM PCOM Psychology Dissertations Student Dissertations, Theses and Papers 2009 Sex Differences in Symptom Presentation of Schizotypal Personality Disorder in First-Degree Family Members of Individuals with Schizophrenia Alexandra Duncan-Ramos Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.pcom.edu/psychology_dissertations Part of the Clinical Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Duncan-Ramos, Alexandra, "Sex Differences in Symptom Presentation of Schizotypal Personality Disorder in First-Degree Family Members of Individuals with Schizophrenia" (2009). PCOM Psychology Dissertations. Paper 40. This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Dissertations, Theses and Papers at DigitalCommons@PCOM. It has been accepted for inclusion in PCOM Psychology Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@PCOM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine Department of Psychology SEX DIFFERENCES IN SYMPTOM PRESENTATION OF SCHIZOTYPAL PERSONALITY DISORDER IN FIRST-DEGREE FAMILY MEMBERS OF INDIVIDUALS WITH SCHIZOPHRENIA By Alexandra Duncan-Ramos, M.S., M.S. Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Psychology July 2009 PHILADELPHIA COLLEGE OF OSTEOPATHIC MEDICINE DEPARTMENT OF PSYCHOLOGY Dissertation Approval This is to certify that the thesis presented to us by Alexandra Duncan-Ramos on the 23rd day of July, 2009 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Psychology, has been examined and is acceptable in both scholarship and literary quality. Committee Members' Signatures: Barbara Golden, Psy.D., ABPP, Chairperson Brad Rosenfield, Psy.D. Monica E. Calkins, Ph.D. -

The Clinical Presentation of Psychotic Disorders Bob Boland MD Slide 1

The Clinical Presentation of Psychotic Disorders Bob Boland MD Slide 1 Psychotic Disorders Slide 2 As with all the disorders, it is preferable to pick Archetype one “archetypal” disorder for the category of • Schizophrenia disorder, understand it well, and then know the others as they compare. For the psychotic disorders, the diagnosis we will concentrate on will be Schizophrenia. Slide 3 A good way to organize discussions of Phenomenology phenomenology is by using the same structure • The mental status exam as the mental status examination. – Appearance –Mood – Thought – Cognition – Judgment and Insight Clinical Presentation of Psychotic Disorders. Slide 4 Motor disturbances include disorders of Appearance mobility, activity and volition. Catatonic – Motor disturbances • Catatonia stupor is a state in which patients are •Stereotypy • Mannerisms immobile, mute, yet conscious. They exhibit – Behavioral problems •Hygiene waxy flexibility, or assumption of bizarre • Social functioning – “Soft signs” postures as most dramatic example. Catatonic excitement is uncontrolled and aimless motor activity. It is important to differentiate from substance-induced movement disorders, such as extrapyramidal symptoms and tardive dyskinesia. Slide 5 Disorders of behavior may involve Appearance deterioration of social functioning-- social • Behavioral Problems • Social functioning withdrawal, self neglect, neglect of • Other – Ex. Neuro soft signs environment (deterioration of housing, etc.), or socially inappropriate behaviors (talking to themselves in -

Living with Serious Mental Illness: the Role of Personal Loss in Recovery and Quality of Life

LIVING WITH SERIOUS MENTAL ILLNESS: THE ROLE OF PERSONAL LOSS IN RECOVERY AND QUALITY OF LIFE Danielle Nicole Potokar A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2008 Committee: Catherine Stein, Ph.D., Advisor Alexander Goberman, Ph.D., Graduate Faculty Representative Dryw Dworsky, Ph.D. Jennifer Gillespie, Ph.D. © 2008 Danielle Nicole Potokar All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Catherine Stein, Ph.D., Advisor As the mental health field is moving towards a recovery based model of serious mental illness for both conceptualization and treatment, further research into the factors which may impact recovery and quality of life are needed. Currently, there are no studies which examine how personal loss due to mental illness or cognitive insight relate to factors such as quality of life and recovery. The purpose of the present study was to investigate the relative contribution of demographic factors, self-reports of psychiatric symptoms, and individual factors of cognitive insight and personal loss in describing variation in reports of quality of life and recovery from mental illness. It was hypothesized that cognitive insight and personal loss would each predict a significant portion of the variance in scores of quality of life and recovery from mental illness. A sample of 65 veterans with serious mental illness from the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Medical Center completed structured interviews regarding psychiatric symptomotology and quality of life and completed questionnaires related to demographics, cognitive insight, personal loss due to mental illness, and recovery. Thirteen significant hierarchical regression models emerged. -

Introduction to Agitation, Delirium, and Psychosis Curriculum for Psychologists/Social Workers

FACILITATOR MANUAL ENGLISH-HAITI Introduction to Agitation, Delirium, and Psychosis Curriculum for Psychologists/Social Workers Introduction to Agitation, Delirium, and Psychosis Curriculum for Psychologists/Social Workers Partners In Health (PIH) is an independent, non-profit organization founded over twenty years ago in Haiti with a mission to provide the very best medical care in places that had none, to accompany patients through their care and treatment, and to address the root causes of their illness. Today, PIH works in fourteen countries with a comprehensive approach to breaking the cycle of poverty and disease — through direct health-care delivery as well as community-based interventions in agriculture and nutrition, housing, clean water, and income generation. PIH’s work begins with caring for and treating patients, but it extends far beyond to the transformation of communities, health systems, and global health policy. PIH has built and sustained this integrated approach in the midst of tragedies like the devastating earthquake in Haiti. Through collaboration with leading medical and academic institutions like Harvard Medical School and the Brigham & Women’s Hospital, PIH works to disseminate this model to others. Through advocacy efforts aimed at global health funders and policymakers, PIH seeks to raise the standard for what is possible in the delivery of health care in the poorest corners of the world. PIH works in Haiti, Russia, Peru, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Liberia Lesotho, Malawi, Kazakhstan, Mexico and the United States. For more information about PIH, please visit www.pih.org. Many PIH and Zanmi Lasante staff members and external partners contributed to the development of this training. -

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) for Schizophrenia: a Meta-Analysis

Running head: COGNITIVE BEHAVIOURAL THERAPY (CBT) FOR SCHIZOPRENIA Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) for Schizophrenia: A Meta-Analysis Gemma Holton BA (Hons) A report submitted in partial requirement for the degree of Master of Psychology (Clinical) at the University of Tasmania October 2015 COGNITIVE BEHAVIOURAL THERAPY (CBT) FOR SCHIZOPHRENIA I declare that this research report is my own work, and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it does not contain material from published sources without acknowledgement, nor does it contain material which has been accepted for the award for any other higher degree or graduate diploma in any university. Gemma Holton ii COGNITIVE BEHAVIOURAL THERAPY (CBT) FOR SCHIZOPHRENIA Acknowledgements I wish to express my thanks to my supervisor Dr Bethany Wootton for her considerate support throughout this project. I am extremely grateful for all the practical advice and continual support and encouragement she gave. Dr Wootton encouraged me to complete my thesis in an area of my interest and never expressed any doubt in my ability. Her methodical and consistent approach, patience and valuable advice are truly appreciated. I thank the staff of RFT who understood my vision when I informed them I was returning to university to complete my Masters in clinical psychology. RFT have been immensely supportive throughout this degree, encouraging me to achieve and share my knowledge, and share my valuable time. To my family and friends, I would like to say a big thank you for encouraging me to return to university and finish what I began. Thank you for supporting me and understanding how much time was dedicated to completing my studies. -

Schizophrenia- What You Need to Know

SCHIZOPHRENIA- WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW BY CATHY CYWINSKI, MSW LCSW SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF SCHIZOPHRENIA • Hallucinations- false perception • Delusions –fixed false belief • Grossly Disorganized Speech and Behavior • Tend to dress and act in odd ways • Flat Affect SYMPTOMS • Hallucinations-can occur with any of the five senses: • Auditory hallucinations • Visual hallucinations • Tactile hallucinations • Olfactory hallucinations • Gustatory hallucinations SYMPTOMS • Bizarre delusion – this simply translated means a delusion regarding something that CANNOT possibly happen. • Nonbizarre delusion – this is a delusion regarding something that CAN possibly happen. COMMON TYPES OF DELUSIONS • Grandiose • Erotomanic • Religious • Delusions of Control • Persecutory • Referential SYMPTOMS • Disorganized Speech • Loose associations- may go from one topic to another with no clear logic • Tangentiality- answers to questions may be obliquely related or completely unrelated • Incoherence or word salad- speech may be so severely disorganized that it is nearly incomprehensible SYMPTOMS • Grossly disorganized behavior • A person may appear disheveled, may dress in an unusual manner (many layers of clothes on a hot day), or may display inappropriate sexual behavior. • Alogia-poverty of speech- brief, empty replies • Avolition- inability to initiate and persist in goal directed activates. The person may sit for long periods of time and show little interest in participating in work or social activities. • Catatonic motor behaviors- a marked decrease in reactivity to the environments. SYMPTOMS • Negative Symptoms • Affect flattening- a person’s face appearing immobile and unresponsive, with poor eye contact and reduced body language IS THERE SOMETHING TO FEAR • Myth: People with a severe mental illness are violent and unpredictable. • Fact: The vast majority of people with mental health problems are no more likely to be violent than anyone else. -

The Differential Diagnosis of Excessive Daytime Sleepiness And

Case Reports The Differential Diagnosis of Excessive Daytime Sleepiness and Cognitive Deficits in a Patient with Delirium, Schizophrenia and Possible Narcolepsy: A Case Report David R. Spiegel 1, Parker W. Babington 1, Ariane M. Abcarian 1, Christian De Filippo 1 Abstract Narcolepsy and schizophrenia are disorders which share common features of negative symptoms, excessive daytime sleepiness and cognitive deficits. Presented here is a case report of a fifty-nine year old man with a past medical history of schizophrenia who was evaluated for suspected symptoms of delirium. After an electroencephalogram was per- formed with surprising results, the patient’s differential diagnosis included schizophrenia with comorbid narcolepsy. We present emerging evidence that excessive daytime sleepiness and attentional deficits in both narcolepsy and schizo- phrenia may share a common pathophysiological pathway through orexin deficiency and its effects on the dopamine system. Finally, we discuss the potential for modafinil as a treatment for excessive daytime sleepiness and attentional problems in schizophrenia and narcolepsy. Key Words: Cognition, Schizophrenia, Sedation, Sleep, Dopamine Introduction The hallmarks of delirium as described by the Diagnostic including the positive symptoms of delusions, hallucina- and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, tions, disorganized speech and grossly disorganized or cata- Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) are a disturbance of conscious- tonic behavior, and negative symptoms such as flattened af- ness with reduced ability to focus, sustain or shift attention. fect, alogia and avolition (1). Patients with schizophrenia Also present is a change in cognition, such as memory defi- also have cognitive deficits, including poor attention span. cit, disorientation or language impairment, or a perceptual Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep onset disorders such disturbance. -

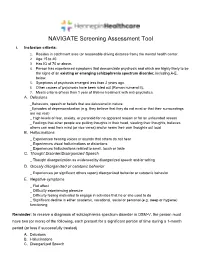

NAVIGATE Screening Assessment Tool

NAVIGATE Screening Assessment Tool I. Inclusion criteria: 1. Resides in catchment area (or reasonable driving distance from) the mental health center. 2. Age 15 to 40. 3. Has IQ of 70 or above. 4. Person has experienced symptoms that demonstrate psychosis and which are highly likely to be the signs of an existing or emerging schizophrenia spectrum disorder, including A-E, below. 5. Symptoms of psychosis emerged less than 2 years ago. 6. Other causes of psychosis have been ruled out (Roman numeral II). 7. Meets criteria of less than 1 year of lifetime treatment with anti-psychotics. A. Delusions _Behaviors, speech or beliefs that are delusional in nature _Episodes of depersonalization (e.g. they believe that they do not exist or that their surroundings are not real) _ High levels of fear, anxiety, or paranoid for no apparent reason or for an unfounded reason _ Feelings that other people are putting thoughts in their head, stealing their thoughts, believes others can read their mind (or vice versa) and/or hears their own thoughts out loud B. Hallucinations _ Experiences hearing voices or sounds that others do not hear _ Experiences visual hallucinations or distortions _ Experiences hallucinations related to smell, touch or taste C. Thought Disorder/Disorganized Speech _ Thought disorganization as evidenced by disorganized speech and/or writing D. Grossly disorganized or catatonic behavior _ Experiences (or significant others report) disorganized behavior or catatonic behavior E. Negative symptoms _ Flat affect _ Difficulty experiencing pleasure _ Difficulty feeling motivated to engage in activities that he or she used to do _ Significant decline in either academic, vocational, social or personal (e.g. -

Negative Symptoms- an Update

Galore International Journal of Health Sciences and Research Vol.4; Issue: 1; Jan.-March 2019 Website: www.gijhsr.com Review Article P-ISSN: 2456-9321 Negative Symptoms- an Update Dr Pavithra P. Rao1, Dr Preethi Rebello2, Dr P. John Mathai3 1Assistant Professor, Department of Psychiatry. Father Muller Medical College, Mangalore, Karnataka, India. 2Senior Resident, Department of Psychiatry, Father Muller Medical College, Mangalore, Karnataka, India. 3Professor. Department of Psychiatry, Jubilee Mission Medical College, East Fort Thrissur. Kerala. India. Corresponding Author: Dr P. John Mathai ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION Negative symptoms (NS) are Negative Symptoms in psychiatry are deficits in abnormal absence of normal behaviour and experience and behavior that are attributed to experience, attributed to the loss of normal loss of functions of brain. Negative symptoms functions of the brain. The NS are defined have been conceptualized as the core aspect of as absence of experience/behaviour that schizophrenia and have been recognized as [1] important ever since the days of Griesinger, should have been present. They are Kraepelin and Bleuler. But over the years the general descriptive terms used for the significance of the negative symptoms was various clinical manifestations of the deleted and emphasis was placed almost diminished capacity for ordinary exclusively on positive symptoms. The return of behavioural functioning (behavioural negative symptoms in schizophrenia was deficits). [2] Though there are differences in inevitable. The five general categories of the language used to refer to NS such as, negative symptoms include avolition, deficits symptoms, defect state symptoms, anhedonia, affective blunting, alogia and type II symptoms, core symptoms, asociality. The subdomains of negative fundamental symptoms, primary symptoms symptoms are experience domain (avolition and and basic symptoms, there are definite anhedonia) and expressivity domain (affective [3-7] blunting and alogia). -

Deficits in Positive Reinforcement Learning and Uncertainty-Driven

Deficits in Positive Reinforcement Learning and Uncertainty-Driven Exploration Are Associated with Distinct Aspects of Negative Symptoms in Schizophrenia Gregory P. Strauss, Michael J. Frank, James A. Waltz, Zuzana Kasanova, Ellen S. Herbener, and James M. Gold Background: Negative symptoms are core features of schizophrenia (SZ); however, the cognitive and neural basis for individual negative symptom domains remains unclear. Converging evidence suggests a role for striatal and prefrontal dopamine in reward learning and the exploration of actions that might produce outcomes that are better than the status quo. The current study examines whether deficits in reinforcement learning and uncertainty-driven exploration predict specific negative symptom domains. Methods: We administered a temporal decision-making task, which required trial-by-trial adjustment of reaction time to maximize reward receipt, to 51 patients with SZ and 39 age-matched healthy control subjects. Task conditions were designed such that expected value (probability ϫ magnitude) increased, decreased, or remained constant with increasing response times. Computational analyses were applied to estimate the degree to which trial-by-trial responses are influenced by reinforcement history. Results: Individuals with SZ showed impaired Go learning but intact NoGo learning relative to control subjects. These effects were most pronounced in patients with higher levels of negative symptoms. Uncertainty-based exploration was substantially reduced in individuals with SZ and selectively correlated with clinical ratings of anhedonia. Conclusions: Schizophrenia patients, particularly those with high negative symptoms, failed to speed reaction times to increase positive outcomes and showed reduced tendency to explore when alternative actions could lead to better outcomes than the status quo.