What Can Taylor Swift Do for Your Latin Prose Composition Students? Using Popular Music to Teach Latin Poetry Analysis Skills.1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sell-Out West End Hit Show the SIMON and GARFUNKEL STORY Comes to New Brighton As Part of a UK Tour

PRESS RELEASE The sell-out West End hit show THE SIMON AND GARFUNKEL STORY comes to New Brighton as part of a UK Tour Following its WEST END success at London’s Leicester Square Theatre in February 2015, The Simon and Garfunkel Story is currently the No 1 touring theatre show celebrating the lives and career of this folk/rock duo sensation. Starring Dean Elliot (Paul Simon) and David Tudor (Art Garfunkel), and directed by David Beck, The Simon and Garfunkel Story comes to New Brighton’s Floral Pavilion Theatre on Thursday 3 rd September 2015. The Simon and Garfunkel Story tells the fascinating tale of how two young boys from Queens, New York went on to become the world’s most successful music duo of all time. Starting from their humble beginnings as 50’s Rock n Roll duo ‘Tom & Jerry’, the show takes you through all the songs and stories that shaped them, the dramatic split, their individual solo careers and ending with a stunning recreation of the legendary 1981 Central Park reunion concert. LIPA trained actor and musician Dean Elliott rose to fame in the lead role as Buddy Holly in the West End, Olivier Award nominated musical Buddy – The Buddy Holly Story . In this role he had the honour of opening the 2008 West End Revival at the Duchess Theatre, London and in Buddy’s hometown of Lubbock, Texas before taking the role around Europe and Canada. Other notable theatre work includes Over The Rainbow – The Eva Cassidy Story (UK No1 Tour), Release The Beat (Arcola Theatre, London) and the multi award winning Ed – The Musical (Edinburgh Festival). -

National Arts Awards Monday, October 19, 2015

2015 Americans for the Arts National Arts Awards Monday, October 19, 2015 Welcome from Robert L. Lynch Performance by YoungArts Alumni President and CEO of Americans for the Arts Musical Director, Jake Goldbas Philanthropy in the Arts Award Legacy Award Joan and Irwin Jacobs Maria Arena Bell Presented by Christopher Ashley Presented by Jeff Koons Outstanding Contributions to the Arts Award Young Artist Award Herbie Hancock Lady Gaga 1 Presented by Paul Simon Presented by Klaus Biesenbach Arts Education Award Carolyn Clark Powers Alice Walton Lifetime Achievement Award Presented by Agnes Gund Sophia Loren Presented by Rob Marshall Dinner Closing Remarks Remarks by Robert L. Lynch and Abel Lopez, Chair, introduction of Carolyn Clark Powers Americans for the Arts Board of Directors and Robert L. Lynch Remarks by Carolyn Clark Powers Chair, National Arts Awards Greetings from the Board Chair and President Welcome to the 2015 National Arts Awards as Americans for the Arts celebrates its 55th year of advancing the arts and arts education throughout the nation. This year marks another milestone as it is also the 50th anniversary of President Johnson’s signing of the act that created America’s two federal cultural agencies: the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities. Americans for the Arts was there behind the scenes at the beginning and continues as the chief advocate for federal, state, and local support for the arts including the annual NEA budget. Each year with your help we make the case for the funding that fuels creativity and innovation in communities across the United States. -

U2 Go One on One with Fans for In-Depth Q&A Session As Part Of

U2 Go One on One with Fans for In-Depth Q&A Session as Part of SiriusXM's Town Hall Series Bono, The Edge, Adam Clayton and Larry Mullen, Jr. sit down with a live audience at the SiriusXM studios in New York City NEW YORK, Aug. 3, 2015 /PRNewswire/ -- SiriusXM announced today that one of the most significant rock bands of all time, U2, sat down for an intimate Q&A session with a select group of listeners for the SiriusXM "Town Hall" series at the SiriusXM studios in New York City. Bono, The Edge, Adam Clayton and Larry Mullen, Jr. answered questions from SiriusXM listeners about their celebrated career, everything from the very early days of the band when bassist Adam Clayton was their manager and The Edge's mother was the first U2 roadie, to the future of music streaming and distribution to their most recent album Songs of Innocence and their current tour "iNNOCENCE + eXPERIENCE Tour 2015." "On a night off during their 8-night, sold-out residency at Madison Square Garden, one of the world's biggest bands came to SiriusXM and delivered to our listeners and some very lucky subscribers a once-in-a-lifetime chance to be just inches away from their music heroes and ask them questions. And, at the end, as a surprise, the band invited the SiriusXM Town Hall guests to attend their sold-out show at MSG on July 30—it was truly a memorable and special event—sure to make for an outstanding broadcast," said Scott Greenstein, President and Chief Content Officer, SiriusXM. -

VILLAGE of OSSINING MUNICIPAL BUILDING 16 Croton Avenue Ossining, N

VILLAGE OF OSSINING MUNICIPAL BUILDING 16 Croton Avenue Ossining, N. Y. 10562 (914) 941-3554 FAX (914) 941-5940 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Christina Papes 914-941-3554 Rock & Roll Hall of Fame member Richie Furay to headline Words & Music Benefit Concert…The Words & Music concert series’ spring benefit concert “AN EVENING WITH RICHIE FURAY” will take place on Friday, May 2 at 8:00pm in the 200 seat Budarz Theater at the Ossining Public Library. Tickets are on sale now and can be purchased at http://wordsandmusic.brownpapertickets.com/ For this intimate performance at the Budarz theater that will trace his musical journey, Richie will be joined by long time musical collaborator Scott Sellen on guitar, banjo, piano and vocals and daughter Jesse Furay Lynch on vocals. Special guest JOHN BATDORF will open with a solo acoustic set. In 1966 RICHIE FURAY joined forces with Stephen Stills & Neil Young to form Buffalo Springfield. Although they were only together for two years, the band was one of the most influential of its era, earning Rock & Roll Hall of Fame recognition in 1997.After Buffalo Springfield disbanded, Richie and Jimmy Messina formed Poco, a band that was part of the first wave of the West Coast country rock genre and whose unique sound shaped musical styles for years to come. In 1974 Richie left Poco to form the Souther-Hillman-Furay Band and later embarked on a solo career that has spanned four decades. JOHN BATDORF has enjoyed a long and varied career, first rising to national prominence in 1971 as a member of the acoustic folk duo Batdorf & Rodney. -

Teaching Latin Love Poetry with Pop Music1

Teaching Classical Languages Volume 10, Issue 2 Kopestonsky 71 Never Out of Style: Teaching Latin Love Poetry with Pop Music1 Theodora B. Kopestonsky University of Tennessee, Knoxville ABSTRACT Students often struggle to interpret Latin poetry. To combat the confusion, teachers can turn to a modern parallel (pop music) to assist their students in understanding ancient verse. Pop music is very familiar to most students, and they already trans- late its meaning unconsciously. Building upon what students already know, teach- ers can reframe their approach to poetry in a way that is more effective. This essay shows how to present the concept of meter (dactylic hexameter and elegy) and scansion using contemporary pop music, considers the notion of the constructed persona utilizing a modern musician, Taylor Swift, and then addresses the pattern of the love affair in Latin poetry and Taylor Swift’s music. To illustrate this ap- proach to connecting ancient poetry with modern music, the lyrics and music video from one song, Taylor Swift’s Blank Space (2014), are analyzed and compared to poems by Catullus. Finally, this essay offers instructions on how to create an as- signment employing pop music as a tool to teach poetry — a comparative analysis between a modern song and Latin poetry in the original or in translation. KEY WORDS Latin poetry, pedagogy, popular music, music videos, song lyrics, Taylor Swift INTRODUCTION When I assign Roman poetry to my classes at a large research university, I re- ceive a decidedly unenthusiastic response. For many students, their experience with poetry of any sort, let alone ancient Latin verse, has been fraught with frustration, apprehension, and confusion. -

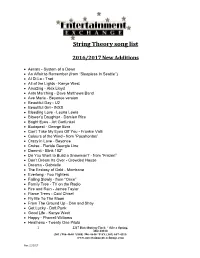

String Theory Song List

String Theory song list 2016/2017 New Additions Aerials - System of a Down An Affair to Remember (from “Sleepless In Seattle”) Al Di La - Trad All of the Lights - Kanye West Amazing - Alex Lloyd Ants Marching - Dave Matthews Band Ave Maria - Beyonce version Beautiful Day - U2 Beautiful Girl - INXS Bleeding Love - Leona Lewis Blower’s Daughter - Damien Rice Bright Eyes - Art Garfunkel Budapest - George Ezra Can’t Take My Eyes Off You - Frankie Valli Colours of the Wind - from “Pocahontas” Crazy in Love - Beyonce Cruise - Florida Georgia Line Dammit - Blink 182* Do You Want to Build a Snowman? - from “Frozen” Don’t Dream Its Over - Crowded House Dreams - Gabrielle The Ecstasy of Gold - Morricone Everlong - Foo Fighters Falling Slowly - from “Once” Family Tree - TV on the Radio Fire and Rain - James Taylor Flame Trees - Cold Chisel Fly Me To The Moon From The Ground Up - Dan and Shay Get Lucky - Daft Punk Good Life - Kanye West Happy - Pharrell Williams Heathens - Twenty One Pilots 1 2217 Distribution Circle * Silver Spring, MD 20910 (301) 986-4640 *(888) 986-4640 *FAX (301) 657-4315 www.entertainmentexchange.com Rev: 11/2017 Here With Me - Dido Hey Soul Sister - Train Hey There Delilah - Plain White T’s High - Lighthouse Family Hoppipola - Sigur Ros Horse To Water - Tall Heights I Choose You - Sara Bareilles I Don’t Wanna Miss a Thing - Aerosmith I Follow Rivers - Lykke Li I Got My Mind Set On You - George Harrison I Was Made For Loving You - Tori Kelly & Ed Sheeran I Will Wait - Mumford & Sons -

Bad Habit Song List

BAD HABIT SONG LIST Artist Song 4 Non Blondes Whats Up Alanis Morissette You Oughta Know Alanis Morissette Crazy Alanis Morissette You Learn Alanis Morissette Uninvited Alanis Morissette Thank You Alanis Morissette Ironic Alanis Morissette Hand In My Pocket Alice Merton No Roots Billie Eilish Bad Guy Bobby Brown My Prerogative Britney Spears Baby One More Time Bruno Mars Uptown Funk Bruno Mars 24K Magic Bruno Mars Treasure Bruno Mars Locked Out of Heaven Chris Stapleton Tennessee Whiskey Christina Aguilera Fighter Corey Hart Sunglasses at Night Cyndi Lauper Time After Time David Guetta Titanium Deee-Lite Groove Is In The Heart Dishwalla Counting Blue Cars DNCE Cake By the Ocean Dua Lipa One Kiss Dua Lipa New Rules Dua Lipa Break My Heart Ed Sheeran Blow BAD HABIT SONG LIST Artist Song Elle King Ex’s & Oh’s En Vogue Free Your Mind Eurythmics Sweet Dreams Fall Out Boy Beat It George Michael Faith Guns N’ Roses Sweet Child O’ Mine Hailee Steinfeld Starving Halsey Graveyard Imagine Dragons Whatever It Takes Janet Jackson Rhythm Nation Jessie J Price Tag Jet Are You Gonna Be My Girl Jewel Who Will Save Your Soul Jo Dee Messina Heads Carolina, Tails California Jonas Brothers Sucker Journey Separate Ways Justin Timberlake Can’t Stop The Feeling Justin Timberlake Say Something Katy Perry Teenage Dream Katy Perry Dark Horse Katy Perry I Kissed a Girl Kings Of Leon Sex On Fire Lady Gaga Born This Way Lady Gaga Bad Romance Lady Gaga Just Dance Lady Gaga Poker Face Lady Gaga Yoü and I Lady Gaga Telephone BAD HABIT SONG LIST Artist Song Lady Gaga Shallow Letters to Cleo Here and Now Lizzo Truth Hurts Lorde Royals Madonna Vogue Madonna Into The Groove Madonna Holiday Madonna Border Line Madonna Lucky Star Madonna Ray of Light Meghan Trainor All About That Bass Michael Jackson Dirty Diana Michael Jackson Billie Jean Michael Jackson Human Nature Michael Jackson Black Or White Michael Jackson Bad Michael Jackson Wanna Be Startin’ Something Michael Jackson P.Y.T. -

PAUL SIMON and ROBERT PLANT Move to NEWCASTLE ENTERTAINMENT CENTRE

PAUL SIMON AND ROBERT PLANT move to NEWCASTLE ENTERTAINMENT CENTRE Saturday 30th March PAUL SIMON Special Guest: Rufus Wainwright Platinum Reserved Seating $199 / Gold Reserved Seating $149 / Silver Reserved Seating $99 (plus handling and payment processing fees) Sunday 31st March ROBERT PLANT & the Sensational Space Shifters Special Guests: Blind Boys Of Alabama Platinum Reserved Seating $199 / Gold Reserved Seating $149 / Silver Reserved Seating $99 (plus handling and payment processing fees) Saturday 9th March 2013 Chugg Entertainment today confirmed the move of this Easter’s two-fold line-up; Paul Simon and Robert Plant, from the Hunter Valley’s Hope Estate to the Newcastle Entertainment Centre. Each concert will play the same dates previously scheduled: Paul Simon (with Rufus Wainwright) on Saturday 30th March and Robert Plant (with Blind Boys of Alabama) on Sunday 31st March, now at the Newcastle Entertainment Centre. Executive Chairman, Michael Chugg said, “We’re moving to the Newcastle Entertainment Centre, which will be a more intimate environment for these two artists.” Chugg added, “I encourage all fans to take the opportunity to see these two iconic artists. These guys are legends and now Newcastle is seeing them in the most intimate venue on the tour.” Both Paul Simon and Robert Plant will be performing career-spanning sets and promise numerous favourites and greatest hits from their rich catalogues, including their solo careers, and Simon & Garfunkel and Led Zeppelin, respectively. New tickets for the Newcastle Entertainment Centre shows go on-sale at midday this Monday March 11 from ticketek.com.au or 132 849. The Newcastle Entertainment Centre Box Office has extended its hours today until 4pm to assist with enquiries (02 4921 2121) but exchanges will not commence until Thursday March 14. -

Favorite Artists in Today's Music Wrld

May 15, 2020 Created by (doja cat & lil uzi vert) (bruno mars & eminem) (taylor swift & rihanna) Dadaism On each of our pages, you will find a “guess the song” section. This was inspired by the Cut-Up technique, an aleatory literary technique where a written text is cut up word-by-word and then completely rearranged, resulting in a new text. This technique can be traced back to the Dadaists in the 1920s, a group of avant-garde artists located primarily in Europe. Since then, the Cut-Up technique has been used in a variety of other contexts. On our pages, we have taken a popular song from each artist, then used the Dadaist cut-up technique to scramble the lyrics and create a new text. We chose to do this to pay homage to and remind us of the avant-garde artists and the history of avant-garde zines. So, if you would like, take a shot at guessing the songs. The answers are found on the final page. We hope you enjoy our little game and, in the process, are reminded of how all zines began. The Next King of POp BrunoBruno MarsMars AMerican Smooth|King|Unique|Icon|Catchy singer/songwriter POPPOP | | SOUL SOUL | | FUNK FUNK | | R&B R&B REGGAEREGGAE | | ROCK ROCK | | HIP-HOP HIP-HOP Album #3 24K 11-time Magic (2016) had huge Grammy successes, Winner including tons of awards and nominations. 24K Magic: 2018 Grammy named one of AWARDS the best songs of the year by many including Won ALL 6 Billboard, won a Major Grammy for Record of the Guess that song Categories Year (2018) The face when and Cause for stares NOMINATED you I; That’s What I would stops the IN Way while The you LIke: topped whole world; Just I a; Billboard 100s, 2nd Album: 7th #1 single in Thing are; 1st Album: Unorthodox US, won three Just not you; Doo-Wops and Jukebox Grammys for Your and way a; Hooligans Best Song, Best Amazing you’re See amazing you’re; R&B when that smile. -

…Just Listen and Get DEAFACT-Ed

…just listen and get DEAFACT-ed DEAFACT GbR Aureliaweg 6 Stand Oktober 2020 93055 Regensburg Track-Liste Kontakt: Tel.: +49 176 – 64676218 1 4 Minutes Madonna feat. Justin Timberlake Mail: [email protected] 2 A little Party Fergie 3 Ain´t no mountain high enough Marvin Gaye 4 Ain´t nobody Chaka Khan 5 Always there Incognito 6 Amadeus Falco 7 Another Star Stevie Wonder 8 Auf uns Andreas Bourani 9 Augenbling Seeed 10 Baby Love Mothers finest 11 Bad boy for life P. Diddy 12 Back to black Amy Winehouse 13 Baila Zucchero 14 Bang Bang Jessie J 15 Beautiful Pharrell Williams feat. Snoop Dogg 16 Bilder im Kopf Sido 17 Billy Jean Michael Jackson 18 Black & Yellow Wiz Khalifa feat. Snoop Dogg, T-Pain 19 Black or White Michael Jackson 20 Blurred Lines Robin Thicke 21 Break my heart Dua Lipa 22 Break your neck Busta Rhymes 23 Bück dich hoch Deichkind 24 California Girls Katy Perry feat. Snoop Dogg 25 California Love Tupac feat Dr. Dre 26 Can´t hold us Macklemore feat. Ryan Lewis 27 Cant´t stop Red Hot Chili Peppers 28 Can´t touch this MC Hammer 29 Car wash Christina Aguilera feat. Missy Elliot 30 Celebration Kool & the Gang 31 Could U be 2 Fatman Scoop 32 Crazy Britney Spears 33 Crazy in love Beyonce Knowles feat. Jay-Z 34 Cry me a river Justin Timberlake 35 Dear Future Husband Meghan Trainor 36 Déjà vu Beyonce Knowles feat. Jay-Z 37 Deliverance Bubba Sparxxx …just listen and get DEAFACT-ed DEAFACT GbR 38 Dickes B Seeed Aureliaweg 6 39 Die da Fanta 4 93055 Regensburg 40 Dirty Christina Aguilera 41 Disturbia Rihanna Kontakt: 42 Don´t start now Dua Lipa Tel.: +49 176 – 64676218 43 Don´t you worry child Swedish House Mafia Mail: [email protected] 44 Drop it like it´s hot Snoop Dogg feat. -

An Analysis of Figurative Language Used by Adele and Taylor Swift's Selected Song

e-ISSN : 2620 3502 International Journal on Integrated Education p-ISSN : 2615 3785 An Analysis of Figurative Language Used By Adele And Taylor Swift’s Selected Song Endi Prasetyo Rusdiyanto, Yuli Astutik English Education Study Program, Universitas Muhammadiyah Sidoarjo, Indonesia Jl. Majapahit, 666 B, Sidoarjo [email protected] ABSTRACT This article focuses to analyze of figurative language in the song albums of Adele and Taylor Swift’s.. The writers propose two statements of problem those are; what are figurative languages in Adele and Taylor Swift’s song, and what is the dominant form of figurative language used by Adele and Taylor Swift. The writer uses qualitative method in this research. Finally, the writer found 23 figurative languages from Adele’s song and 22 figurative languages from Taylor Swift song. They are metaphor, personification, simile, hyperbole, paradox, irony, symbol and synecdoche. The dominant form of figurative language by Adele and Taylor Swift is Personification that belongs to comparative figurative language. Keywords: Figurative Language, song, Adele & Taylor Swift 1. INTRODUCTION Every time you describe something by comparing it to another, you use figurative language. Figurative languagae is the use of words, phrases, symbols and ideas in such a way as to generate mental images and impression impressions [1]. Figurative language is often characterized by figurative uses, complicated expressions, sound devices, and syntactic departures from the usual literal language sequence. Along with the times, as now, language also experiences growth in its use, if we know that the style of language is only used in making poetry, short stories or poetry, even in songs. -

Jacknife Lee

Jacknife Lee It is fair to say that Jacknife Lee has become one of the most sought after and highly influential producers currently at work. Lee’s career has encompassed work with some of the biggest and most influential artists on both sides of the Atlantic in the shape of Taylor Swift, U2, R.E.M., Kasabian, Robbie Williams and Neil Diamond. His work on U2’s “How To Dismantle An Atom Bomb” saw him collect two Grammy Awards in 2006 as well as Producer of the Year at the UK MMF Awards. He was also again Grammy nominated in 2013 for his work on Swift’s multi-million selling album “Red.” Currently working on what looks set to be the biggest album from Scottish alt-rock heroes Twin Atlantic and the debut album from The Gossip’s Beth Ditto, Lee has also produced a handful of tracks on Jake Bugg’s upcoming third album and is just about to commence work with Two Door Cinema Club after their successful collaboration on Beacon two years previously. In 2014, Lee was honoured to be asked to co-produce Neil Diamond’s “Melody Road” album alongside the tremendously talented Don Was. “Melody Road” debuted at #3 in America and #4 in the UK as it received universal critical acclaim. Lee has gained much recognition as a writer producer over the last five years. In 2014 also Lee co write and produced various singles for Kodaline’s second album “Coming Up For Air” which peaked at #2, while he also produced and co-wrote Twin Atlantic’s Radio 1 A-listed singles “Heart and Soul” and “Brothers and Sisters.” In addition, Lee spent some of the year writing and producing track for alternative urban artist Raury.