The Waterways of Tangail: Failures to Learn from Flood-Control Efforts in the Brahmaputra Basin of Bangladesh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Baseline Survey on the Availability of Black Bengal Breeding Bucks in Different Districts of Bangladesh

J. Bangladesh Agril. Univ. 9(1): 91–96, 2011 ISSN 1810-3030 A baseline survey on the availability of Black Bengal breeding bucks in different districts of Bangladesh M. A. M. Y. Khandoker, A. S. Apu, S. S. Husain and D. R. Notter1 Department of Animal Breeding and Genetics, Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh-2202, Bangladesh 1Department of Animal and Poultry Sciences, Virginia Polytechnic Institute & State University, USA Email: [email protected] Abstract The present study was conducted to assess the availability of Black Bengal breeding bucks in five districts from the Northern part (Lalmonirhat and Rangpur), Central part (Tangail and Mymensingh) and Southern part (Khulna) of Bangladesh and also to explore the relationship between distance of does from these breeding bucks and type of scarcity. The data were collected using a pre-tested questionnaire from 100 goat rearers of 100 villages in five districts. In this study, the selected characteristics of the respondents and other factors on the availability of Black Bengal breeding bucks were considered as independent variable whereas type of scarcity was considered as dependent variable. The buck and doe ratios were 1:164, 1:138, 1:114, 1:127 and 1:96 in Lalmonirhat, Rangpur, Tangail, Khulna and Mymensingh district, respectively. The pooled buck and doe ratio was 1:128. More than 70% farmers faced severe shortage of breeding bucks for serving their does in the above districts which ultimately represent the overall situation of the country. Almost all farmers (100%) had to depend on natural mating to serve their does except the farmers of Mymensingh where 12% farmers depended on artificial insemination in goat. -

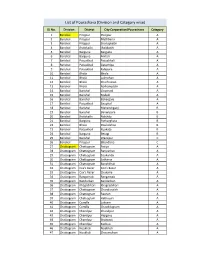

List of Pourashava (Division and Category Wise)

List of Pourashava (Division and Category wise) SL No. Division District City Corporation/Pourashava Category 1 Barishal Pirojpur Pirojpur A 2 Barishal Pirojpur Mathbaria A 3 Barishal Pirojpur Shorupkathi A 4 Barishal Jhalokathi Jhalakathi A 5 Barishal Barguna Barguna A 6 Barishal Barguna Amtali A 7 Barishal Patuakhali Patuakhali A 8 Barishal Patuakhali Galachipa A 9 Barishal Patuakhali Kalapara A 10 Barishal Bhola Bhola A 11 Barishal Bhola Lalmohan A 12 Barishal Bhola Charfession A 13 Barishal Bhola Borhanuddin A 14 Barishal Barishal Gournadi A 15 Barishal Barishal Muladi A 16 Barishal Barishal Bakerganj A 17 Barishal Patuakhali Bauphal A 18 Barishal Barishal Mehendiganj B 19 Barishal Barishal Banaripara B 20 Barishal Jhalokathi Nalchity B 21 Barishal Barguna Patharghata B 22 Barishal Bhola Doulatkhan B 23 Barishal Patuakhali Kuakata B 24 Barishal Barguna Betagi B 25 Barishal Barishal Wazirpur C 26 Barishal Pirojpur Bhandaria C 27 Chattogram Chattogram Patiya A 28 Chattogram Chattogram Bariyarhat A 29 Chattogram Chattogram Sitakunda A 30 Chattogram Chattogram Satkania A 31 Chattogram Chattogram Banshkhali A 32 Chattogram Cox's Bazar Cox’s Bazar A 33 Chattogram Cox's Bazar Chakaria A 34 Chattogram Rangamati Rangamati A 35 Chattogram Bandarban Bandarban A 36 Chattogram Khagrchhari Khagrachhari A 37 Chattogram Chattogram Chandanaish A 38 Chattogram Chattogram Raozan A 39 Chattogram Chattogram Hathazari A 40 Chattogram Cumilla Laksam A 41 Chattogram Cumilla Chauddagram A 42 Chattogram Chandpur Chandpur A 43 Chattogram Chandpur Hajiganj A -

The Waterways of Tangail Failures to Learn from Flood-Control Efforts in the Brahmaputra Basin of Bangladesh Rammelt, C.F.; Masud, Z.M.; Masud, A

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) The Waterways of Tangail Failures to Learn from Flood-Control Efforts in the Brahmaputra Basin of Bangladesh Rammelt, C.F.; Masud, Z.M.; Masud, A. Publication date 2018 Document Version Final published version Published in Water Alternatives License CC BY-NC-SA Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Rammelt, C. F., Masud, Z. M., & Masud, A. (2018). The Waterways of Tangail: Failures to Learn from Flood-Control Efforts in the Brahmaputra Basin of Bangladesh. Water Alternatives, 11(1), 106-124. http://www.water- alternatives.org/index.php/alldoc/articles/vol11/v11issue1/422-a11-1-6 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:25 Sep 2021 www.water-alternatives.org Volume 11 | Issue 1 Rammelt, C.; Md. -

Benefit-Cost Analysis of Deep and Shallow Tubewell Projects in the Tangail District in Bangladesh

Bangladesh J. Agric. Econ., XI, 1 ( June 1988 ) 1-29 BENEFIT-COST ANALYSIS OF DEEP AND SHALLOW TUBEWELL PROJECTS IN THE TANGAIL DISTRICT IN BANGLADESH M. T. H. Miah* and J. B. Hardaker** ABSTRACT This study examines the profitability of deep tubewell (DM and shallow tubewell (STW) projects in the Tangail District in Bangladesh from the viewpoints of participating farmers, managers and society. The appraisal is based on the actual rather than planned levels of utilisation. Only the direct/tangible benefits and costs of these projects are taken into account. Secondary and intangible benefits and costs together with flow- on effects are ignored. The general findings are that the DTW and STW projects are profitable from the viewpoints of participating farmers and managers, but unprofitable from the viewpoint of society. The results of sensitivity analyses reveal that the profitability of these projects is positively related to command areas. 1. INTRODUCTION It has long been realised that the dry season in Bangladesh is the safer for successful crop production, provided irrigation facilities are available. To this end, deep tubewells (DTWs) and shallow tubewells (STWs) h-ive been introduced. A major component of the improved agricultural production technology in Bangladesh is irrigation in the sense that the productivities of other inputs, for example, high yielding variety (HYV) of seeds, fertilisers etc., largely depend on the availability of ensured water supply in the cropfields. *Associate Professor in the Department of Agricultural Economics, Bangladesh Agricultural Uni- versity, Mymensingh, Bangladesh. This paper is based on research completed for his M.Ec. dissertation at the University of New England, Armidale, Australia. -

Bangladesh Cyclone Sidr Was the Second Occasion Habitat for Humanity* Responded to a Natural Disaster in Ban- Gladesh

Habitat for Humanity: The Work Transitional Shelters As480 of December 2008 Latrines As480 of February 2009 A Day in November On 15th November 2007, Cyclone Sidr bore down on southern Bangladesh, unleashing winds that peaked at 250 km. per hour and six-meter high tidal surges that washed away entire villages. Cyclone Sidr killed over 3,000 people, a fraction of the more destructive cyclones that struck in 1970 and 1991 which claimed more than 600,000 lives. But that was still too many. According to reports from the worst hit areas, many of the dead and injured were crushed when trees fell onto poorly constructed houses made of thatch, bam- boo or tin. Others drowned when they, together with their houses, were swept away by the torrents of water. TANGAIL Tangail 15 Nov 18.00 UCT Wind Speed 190 kmph INDIA DHAKA SHARIATPUR BANGLADESH MADARIPUR Madaripur GOPALGANJ Madaripur Gopalganj BARISAL INDIA SATKHIRA Bagrthat JHALAKTHI BAGTHAT Pirojpur PATUAKHALI PIROJPUR KHULNA BHOLA Mirzagani Patuakhali Barguna BARGUNA Bay of Bengal Badly Affected Severely Affected Most Severely Affected Storm Track Worst Affected BURMA 0 50 100 Km TANGAIL Tangail 15 Nov 18.00 UCT Wind Speed 190 kmph INDIA Extent of DHAKA the Damage SHARIATPUR BANGLADESH MADARIPUR More than eight million people in 31 districts were Madaripur reportedly affected by Cyclone Sidr. More than 9,000 GOPALGANJ Madaripur schools were flattened or swept away, with extensive Gopalganj damage reported to roads, bridges and embankments. BARISAL Some two million acres of crops were damaged and INDIA SATKHIRA Bagrthat JHALAKTHI over 1.25 million livestock killed. -

Cropping Pattern, Intensity and Diversity in Dhaka Region

Bangladesh Rice J. 21 (2) : 123-141, 2017 Cropping Pattern, Intensity and Diversity in Dhaka Region N Parvin1*, A Khatun1, M K Quais1 and M Nasim1 ABSTRACT Sustainable crop production in Bangladesh through improvement of cropping intensity and crop diversity in rice based cropping system is regarded as increasingly important in national issues. Planning of agricultural development largely depends on the authentic, reliable and comprehensive statistics of the existing cropping patterns, cropping intensity and crop diversity of a particular area, which will provide guideline to our policy makers, researchers, extensionists and development workers. The study was conducted over all 46 upazilas of Dhaka agricultural region in 2015 using pretested semi-structured questionnaire with a view to document the existing cropping patterns, cropping intensity and crop diversity in the region. From the present study, it was observed that about 48.27% net cropped area (NCA) is covered by exclusive rice cropping systems whereas deep water rice occupied about 16.57% of the regional NCA. The most dominant cropping pattern Boro−Fallow−T. Aman alone occupied about 22.59% of net cropped area (NCA) with its distribution over 32 upazilas out of 46. The second largest area was covered by single Boro cropping pattern, which was spread over 44 upazilas. Total number of cropping patterns was observed 164. The highest number of cropping pattern was identified 35 in Tangail sadar and Dhamrai upazila of Dhaka district and the lowest was seven in Bandar of Narayanganj and Palash of Narsingdi district. The lowest crop diversity index (CDI) was reported as 0.70 in Dhamrai followed by 0.72 in Monohardi of Narsingdi. -

Bangladesh: Human Rights Report 2015

BANGLADESH: HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT 2015 Odhikar Report 1 Contents Odhikar Report .................................................................................................................................. 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................... 4 Detailed Report ............................................................................................................................... 12 A. Political Situation ....................................................................................................................... 13 On average, 16 persons were killed in political violence every month .......................................... 13 Examples of political violence ..................................................................................................... 14 B. Elections ..................................................................................................................................... 17 City Corporation Elections 2015 .................................................................................................. 17 By-election in Dohar Upazila ....................................................................................................... 18 Municipality Elections 2015 ........................................................................................................ 18 Pre-election violence .................................................................................................................. -

Division Zila Upazila Name of Upazila/Thana 10 10 04 10 04

Geo Code list (upto upazila) of Bangladesh As On March, 2013 Division Zila Upazila Name of Upazila/Thana 10 BARISAL DIVISION 10 04 BARGUNA 10 04 09 AMTALI 10 04 19 BAMNA 10 04 28 BARGUNA SADAR 10 04 47 BETAGI 10 04 85 PATHARGHATA 10 04 92 TALTALI 10 06 BARISAL 10 06 02 AGAILJHARA 10 06 03 BABUGANJ 10 06 07 BAKERGANJ 10 06 10 BANARI PARA 10 06 32 GAURNADI 10 06 36 HIZLA 10 06 51 BARISAL SADAR (KOTWALI) 10 06 62 MHENDIGANJ 10 06 69 MULADI 10 06 94 WAZIRPUR 10 09 BHOLA 10 09 18 BHOLA SADAR 10 09 21 BURHANUDDIN 10 09 25 CHAR FASSON 10 09 29 DAULAT KHAN 10 09 54 LALMOHAN 10 09 65 MANPURA 10 09 91 TAZUMUDDIN 10 42 JHALOKATI 10 42 40 JHALOKATI SADAR 10 42 43 KANTHALIA 10 42 73 NALCHITY 10 42 84 RAJAPUR 10 78 PATUAKHALI 10 78 38 BAUPHAL 10 78 52 DASHMINA 10 78 55 DUMKI 10 78 57 GALACHIPA 10 78 66 KALAPARA 10 78 76 MIRZAGANJ 10 78 95 PATUAKHALI SADAR 10 78 97 RANGABALI Geo Code list (upto upazila) of Bangladesh As On March, 2013 Division Zila Upazila Name of Upazila/Thana 10 79 PIROJPUR 10 79 14 BHANDARIA 10 79 47 KAWKHALI 10 79 58 MATHBARIA 10 79 76 NAZIRPUR 10 79 80 PIROJPUR SADAR 10 79 87 NESARABAD (SWARUPKATI) 10 79 90 ZIANAGAR 20 CHITTAGONG DIVISION 20 03 BANDARBAN 20 03 04 ALIKADAM 20 03 14 BANDARBAN SADAR 20 03 51 LAMA 20 03 73 NAIKHONGCHHARI 20 03 89 ROWANGCHHARI 20 03 91 RUMA 20 03 95 THANCHI 20 12 BRAHMANBARIA 20 12 02 AKHAURA 20 12 04 BANCHHARAMPUR 20 12 07 BIJOYNAGAR 20 12 13 BRAHMANBARIA SADAR 20 12 33 ASHUGANJ 20 12 63 KASBA 20 12 85 NABINAGAR 20 12 90 NASIRNAGAR 20 12 94 SARAIL 20 13 CHANDPUR 20 13 22 CHANDPUR SADAR 20 13 45 FARIDGANJ -

Investigation of Soil Properties and Nutrients in Agricultural Practiced Land in Tangail, Bangladesh

ISSN: 2224-0616 Int. J. Agril. Res. Innov. Tech. 10(2): 84-90, December 2020 Available online at https://ijarit.webs.com DOI: https://doi.org/10.3329/ijarit.v10i2.51581 https://www.banglajol.info/index.php/IJARIT Investigation of soil properties and nutrients in agricultural practiced land in Tangail, Bangladesh M.S. Islam*, T. Nusrat, M.R. Jamil, F. Yesmin, M.H. Kabir and R.H. Rimi Received 10 August 2020, Revised 23 November 2020, Accepted 24 December 2020, Published online 31 December 2020 A B S T R A C T The study investigated on soil nutrients in agriculture practiced high, medium high, medium low and low land at Kalihati upazila of Tangail district during October 2017 to June 2018. Thirty soil samples were collected from different land types at the study area and analyzed at Soil Resource Development Institute (SRDI) to determine soil nutrient status. The soil parameters under investigation included pH, organic matter (OM), total nitrogen (N), available phosphorus (P), available zinc (Zn), available iron (Fe), available manganese (Mn), available boron (B), exchangeable potassium (K), exchangeable calcium (Ca) and exchangeable magnesium (Mg). Results indicated that many of the soil nutrient levels decreased such as pH (5.63 to 6.40), P (3.50 to 23.20 µg g-1), Zn (3.27 to 3.60 µg g-1), Mn (21.12 to 57.90 µg g-1), B (0.17 to 0.60 µg g-1), K (0.18 to 0.30 meq 100g-1) and Ca (5.75 to 9.10 meq 100g-1). On the contrary, the average content of OM (2.30 to 1.40%), Fe (248.22 to 161.10 µg g-1) and Mg (2.07 to 1.80 meq 100g-1) were increased. -

Upazila Gopalpur

89°45'0"E 89°50'0"E 89°55'0"E 90°0'0"E N N " " 0 L E G E N D 0 ' ' 0 0 4 4 ° ° 4 UPAZILA DHANBARI 4 2 2 Administrative Boundary ROAD MAP } } } International Boundary 08 Division Boundary z# 52 200 UPAZILA GOPALPUR District Boundary 5 5 51 1 00 5 0 z#{# 1 2 y# 053 Upazila Boundary 0 |y#^% ^%|#1 4 1 0 5 z#2 5062 DISTRICT TANGAIL 5146 0 5 $T 1 Hadira Hat Union Boundary z#5 z#^% z# 4 9 Municipal Boundary 058 02 G 4 5 9 1 z# 0 7 5 0 1 3 3 1 y#z 1 z# 0 5 0 0 2 0 5 y#5 2 0 4 30 $T 2 Administrative Headquarters 1 50 0 7 6 0 z# 50 4 1 5 0 7 8 5 UPAZILA SARISHABARI 3 0 0 z# z# 0 7 3 5 District Bhengula Hat 0 Mahmoodpur Hat 4 [% |^#%y# 20 4 S# 5 0z#2 y# 50 0 4 1 DISTRICT JAMALPUR 7 Hadira 8 0 z# 8 Upazila 6 3 G 4 $ Y# 6 T 1 y# 4 z# G 0 0 1 1 1 5 ^% 1 5 7 0 0 6 ^% 5 5 G 4 0 2 0 5 G T$ Union 4 1 4 |# Nagda Simla 1 ^|%# 5 1 1 5 z# 5 z# $T à 8 0 2 |#|# Sayedpur Hat 7 14 1 300z#2 G |#5 z# 0 5004 21 1 |# UPAZILA MADHUPUR 5 4 4 5 Physical Infrastructures 0 1 2 $TT$ ^% 5 $T5070 5 0 z# 5 z# 0 Niamatpur Hat 1 0 4 2 3 5 1 5 6 1G 7 0 8 9 7 4 0 National Highways 0 0 5 40 507 0 z# z# z# 4 8 5 z# To Sharishabari z# 6 0 Nagda Simla Hat 12 5 z# 50 Jhaoail z# z# Regional Highways 9 4 y# 5167 0 3 1 Chatila Bazar 3 2 5 4 T 1 5 5 0 z#9 z# 2 o 0 5 1 $T 5 0 1 4 |#^%0 0 z# Zila Road z# 50 4 5071 2 2 0 406 0 5 S 50 9 1 5 $T 1 z# 5 2 2 2 2 a 5 5 þ $T 2 |# z# 5 S#T$ z# y# z# 0 Ramnagar Hat z# z# 0 r 0 50 i 14 z# 4 s 0 Upazila Road (Pucca) zy# z# 3 z# $T G h 5 Jhawail Hat y#^% y# a 2013 0 z# 008 4 0 3 ^% b 502 Dhopakandi^% Hat ^% G z# 4 3 |# z# 6 |# z# a 2 5163 5 0 Upazila -

Land Resource Appraisal of Bangladesh for Agricultural

BGD/81/035 Technical Report 3 Volume II LAND RESOURCES APPRAISAL OF BANGLADESH FOR AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENT REPORT 3 LAND RESOURCES DATA BASE VOLUME II SOIL, LANDFORM AND HYDROLOGICAL DATA BASE A /UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME FAo FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION vJ OF THE UNITED NATIONS BGD/81/035 Technical Report 3 Volume II LAND RESOURCES APPRAISAL OF BANGLADESH FOR AGRICULTURALDEVELOPMENT REPORT 3 LAND RESOURCES DATA BASE VOLUME II SOIL, LANDFORM AND HYDROLOGICAL DATA BASE Report prepared for the Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations acting as executing agency for the United Nations Development Programme based on the work of H. Brammer Agricultural Development Adviser J. Antoine Data Base Management Expert and A.H. Kassam and H.T. van Velthuizen Land Resources and Agricultural Consultants UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 1988 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and AgricultureOrganization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored ina retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopyingor otherwise, without the prior perrnission of (he copyright owner. Applications for such permission,with a statement of the purpose and extent of the reproduction, should be addressedto the Director, Publications Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Viadelle Terme di Caracarla, 00100 Home, Italy. -

District Budget Experience in Bangladesh: the Case of Tangail Page 2

District Budget Experience in Bangladesh The Case of Tangail Towfiqul Islam Khan Research Fellow, CPD < [email protected] > Mostafa Amir Sabbih Research Associate, CPD < [email protected] > A report prepared under the programme Independent Review of Bangladesh’s Development (IRBD) of the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD) Presented at the PRE-BUDGET DIALOGUE 2015 TANGAIL DISTRICT BUDGET AND RELEVANT ISSUES Tangail: 14 March 2015 Contents SECTION 1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................................. 3 SECTION 2. SOCIO-ECONOMIC STATE OF TANGAIL DISTRICT.......................................................................................... 5 SECTION 3. REVISITING DISTRICT BUDGET IN TANGAIL: METHOD AND ESTIMATION ................................... 15 SECTION 4. TRACING THE CHANGES: IS THERE ANY? ....................................................................................................... 18 SECTION 5. CONCLUDING REMARKS .......................................................................................................................................... 20 REFERENCES .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 22 ANNEXTURE ..........................................................................................................................................................................................