Introduction to Cocoon 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Log4j-Users-Guide.Pdf

...................................................................................................................................... Apache Log4j 2 v. 2.2 User's Guide ...................................................................................................................................... The Apache Software Foundation 2015-02-22 T a b l e o f C o n t e n t s i Table of Contents ....................................................................................................................................... 1. Table of Contents . i 2. Introduction . 1 3. Architecture . 3 4. Log4j 1.x Migration . 10 5. API . 16 6. Configuration . 18 7. Web Applications and JSPs . 48 8. Plugins . 56 9. Lookups . 60 10. Appenders . 66 11. Layouts . 120 12. Filters . 140 13. Async Loggers . 153 14. JMX . 167 15. Logging Separation . 174 16. Extending Log4j . 176 17. Extending Log4j Configuration . 184 18. Custom Log Levels . 187 © 2 0 1 5 , T h e A p a c h e S o f t w a r e F o u n d a t i o n • A L L R I G H T S R E S E R V E D . T a b l e o f C o n t e n t s ii © 2 0 1 5 , T h e A p a c h e S o f t w a r e F o u n d a t i o n • A L L R I G H T S R E S E R V E D . 1 I n t r o d u c t i o n 1 1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 1.1 Welcome to Log4j 2! 1.1.1 Introduction Almost every large application includes its own logging or tracing API. In conformance with this rule, the E.U. -

Web Application Firewall Security Advisory

Web Application Firewall Web Application Firewall Security Advisory Product Documentation ©2013-2019 Tencent Cloud. All rights reserved. Page 1 of 20 Web Application Firewall Copyright Notice ©2013-2019 Tencent Cloud. All rights reserved. Copyright in this document is exclusively owned by Tencent Cloud. You must not reproduce, modify, copy or distribute in any way, in whole or in part, the contents of this document without Tencent Cloud's the prior written consent. Trademark Notice All trademarks associated with Tencent Cloud and its services are owned by Tencent Cloud Computing (Beijing) Company Limited and its affiliated companies. Trademarks of third parties referred to in this document are owned by their respective proprietors. Service Statement This document is intended to provide users with general information about Tencent Cloud's products and services only and does not form part of Tencent Cloud's terms and conditions. Tencent Cloud's products or services are subject to change. Specific products and services and the standards applicable to them are exclusively provided for in Tencent Cloud's applicable terms and conditions. ©2013-2019 Tencent Cloud. All rights reserved. Page 2 of 20 Web Application Firewall Contents Security Advisory Command Execution Vulnerability in Exchange Server SQL Injection Vulnerability in Yonyou GRP-U8 XXE Vulnerability in Apache Cocoon (CVE-2020-11991) Arbitrary Code Execution Vulnerability in WordPress File Manager Jenkins Security Advisory for September Remote Code Execution Vulnerabilities in Apache Struts 2 (CVE-2019-0230 and CVE-2019- 0233) SQL Injection Vulnerability in Apache SkyWalking (CVE-2020-13921) ©2013-2019 Tencent Cloud. All rights reserved. Page 3 of 20 Web Application Firewall Security Advisory Command Execution Vulnerability in Exchange Server Last updated:2020-12-15 15:20:26 On September 17, 2020, Tencent Security detected that Microsoft issued a security advisory for a command execution vulnerability in Exchange Server (CVE-2020-16875). -

Návrhy Internetových Aplikací

Bankovní institut vysoká škola Praha Katedra informačních technologií a elektronického obchodování Návrhy internetových aplikací Bakalářská práce Autor: Jiří Nachtigall Informační technologie, MPIS Vedoucí práce: Ing. Jiří Rotschedl Praha Srpen, 2010 Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou práci zpracoval samostatně a s použitím uvedené literatury. V Praze, dne 24. srpna 2010 Jiří Nachtigall Poděkování Na tomto místě bych rád poděkoval vedoucímu práce Ing. Jiřímu Rotschedlovi za vedení a cenné rady při přípravě této práce. Dále bych chtěl poděkovat Ing. Josefu Holému ze společnosti Sun Microsystems za odbornou konzultaci. Anotace Tato práce se zaměřuje na oblast návrhu internetových aplikací. Podrobně popisuje celý proces návrhu počínaje analýzou za použití k tomu určených nástrojů jako je use case a user story. Další částí procesu je návrh technologického řešení, které se skládá z výběru serverového řešení, programovacích technik a databází. Jako poslední je zmíněn návrh uživatelského rozhraní pomocí drátěných modelů a návrh samotného designu internetové aplikace. Annotation This work focuses on web application design. It describes whole process of design in detail. It starts with analysis using some tools especially created for this purpose like use case and user story. Next part of the process is technical design which consists from selection of server solution, programming language and database. And finally user interface prepared using wireframes is mentioned here alongside with graphical design of the web application. Obsah Úvod -

Open Source Used in Cisco Unity Connection 11.5 SU 1

Open Source Used In Cisco Unity Connection 11.5 SU 1 Cisco Systems, Inc. www.cisco.com Cisco has more than 200 offices worldwide. Addresses, phone numbers, and fax numbers are listed on the Cisco website at www.cisco.com/go/offices. Text Part Number: 78EE117C99-132949842 Open Source Used In Cisco Unity Connection 11.5 SU 1 1 This document contains licenses and notices for open source software used in this product. With respect to the free/open source software listed in this document, if you have any questions or wish to receive a copy of any source code to which you may be entitled under the applicable free/open source license(s) (such as the GNU Lesser/General Public License), please contact us at [email protected]. In your requests please include the following reference number 78EE117C99-132949842 Contents 1.1 ace 5.3.5 1.1.1 Available under license 1.2 Apache Commons Beanutils 1.6 1.2.1 Notifications 1.2.2 Available under license 1.3 Apache Derby 10.8.1.2 1.3.1 Available under license 1.4 Apache Mina 2.0.0-RC1 1.4.1 Available under license 1.5 Apache Standards Taglibs 1.1.2 1.5.1 Available under license 1.6 Apache STRUTS 1.2.4. 1.6.1 Available under license 1.7 Apache Struts 1.2.9 1.7.1 Available under license 1.8 Apache Xerces 2.6.2. 1.8.1 Notifications 1.8.2 Available under license 1.9 axis2 1.3 1.9.1 Available under license 1.10 axis2/cddl 1.3 1.10.1 Available under license 1.11 axis2/cpl 1.3 1.11.1 Available under license 1.12 BeanUtils(duplicate) 1.6.1 1.12.1 Notifications Open Source Used In Cisco Unity Connection -

Web Development with Java

Web Development with Java Tim Downey Web Development with Java Using Hibernate, JSPs and Servlets Tim Downey, BS, MS Florida International University Miami, FL 33199, USA British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Control Number: 2007925710 ISBN: 978-1-84628-862-3 e-ISBN: 978-1-84628-863-0 Printed on acid-free paper © Springer-Verlag London Limited 2007 Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the pub- lishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers. The use of registered names, trademarks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifi c statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher makes no representation, express or implied, with regard to the accuracy of the informa- tion contained in this book and cannot accept any legal responsibility or liability for any errors or omissions that may be made. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Springer Science+Business Media springer.com To Bobbi, my sweetheart, with all my love. Preface I have been teaching web development for ten years. -

Opensource Webframeworks(Cocoon,Struts

Webframeworks - Teil 2 Cocoon, Jetspeed, Struts und Co. AUTOR Thomas Bayer ) Schulung ) Orientation in Objects GmbH Veröffentlicht am: 1.4.2003 ABSTRACT Nachdem die Frage geklärt wurde, wann ein Framework eingesetzt werden soll, hilft ) Beratung ) Ihnen der zweite Teil bei der Auswahl eines passenden Frameworks. Bei den im Folgenden beschriebenen Frameworks handelt es sich ausschließlich um Open Source Frameworks. Eine kommerzielle Verwendung ist in den meisten Fällen durch die Apache oder LGPL Lizenz möglich. Diese Frameworks sind nicht nur aus Kostengründen immer häufiger in kommerziellen Projekten zu finden. Ein Framework muss leben, es genügt nicht, dass ein Hersteller von Zeit zu Zeit Updates anbietet. Wichtig für die Entscheidung für ein Framework ist die Gemeinschaft der ) Entwicklung ) Entwickler, die das Framework entwickeln und verwenden. Offene Frameworks besitzen meist eine größere Entwicklergemeinde als hochpreisige Produkte. Für diesen Artikel wurden die Frameworks kategorisiert und Überschriften zugeordnet. Die einzelnen Kategorien wie MVC oder Templating Framework gehen teilweise ) ineinander über und sind schwer zu trennen. Besonders das "Schlagwort" MVC beansprucht fast jedes Framework für sich. Artikel ) Trivadis Germany GmbH Weinheimer Str. 68 D-68309 Mannheim Tel. +49 (0) 6 21 - 7 18 39 - 0 Fax +49 (0) 6 21 - 7 18 39 - 50 [email protected] Java, XML, UML, XSLT, Open Source, JBoss, SOAP, CVS, Spring, JSF, Eclipse 5 MVC FRAMEWORKS Die folgenden Jakarta Projekte stehen in enger Beziehung zu Turbine: • Service Framework Fulcrum Fast alle der hier aufgeführten Frameworks behaupten, die Model • Das verteilte Java Caching System JCS View Controller Architektur zu unterstützen. Ein typischer Vertreter, der sich stark auf MVC fürs Web konzentriert, ist Struts. -

Enterprise Development with Flex

Enterprise Development with Flex Enterprise Development with Flex Yakov Fain, Victor Rasputnis, and Anatole Tartakovsky Beijing • Cambridge • Farnham • Köln • Sebastopol • Taipei • Tokyo Enterprise Development with Flex by Yakov Fain, Victor Rasputnis, and Anatole Tartakovsky Copyright © 2010 Yakov Fain, Victor Rasputnis, and Anatole Tartakovsky.. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472. O’Reilly books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. Online editions are also available for most titles (http://my.safaribooksonline.com). For more information, contact our corporate/institutional sales department: (800) 998-9938 or [email protected]. Editor: Mary E. Treseler Indexer: Ellen Troutman Development Editor: Linda Laflamme Cover Designer: Karen Montgomery Production Editor: Adam Zaremba Interior Designer: David Futato Copyeditor: Nancy Kotary Illustrator: Robert Romano Proofreader: Sada Preisch Printing History: March 2010: First Edition. Nutshell Handbook, the Nutshell Handbook logo, and the O’Reilly logo are registered trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc. Enterprise Development with Flex, the image of red-crested wood-quails, and related trade dress are trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and O’Reilly Media, Inc. was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in caps or initial caps. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this book, the publisher and authors assume no responsibility for errors or omissions, or for damages resulting from the use of the information con- tained herein. -

Roller: an Open Source Javatm Ee Blogging Platform

ROLLER: AN OPEN SOURCE JAVATM EE BLOGGING PLATFORM • Dave Johnson – Staff Engineer S/W – Sun Microsystems, Inc. Agenda • Roller history • Roller features • Roller community • Roller internals: backend • Roller internals: frontend • Customizing Roller • Roller futures Roller started as an EJB example... • Homeport – a home page / portal (2001) ... became an O'Reilly article • Ditched EJBs and HAHTsite IDE (2002) • Used all open source tools instead and thus... ... and escaped into the wild I am allowing others to use my installation of Roller for their weblogging. Hopefully this will provide a means for enhancing the Roller user base as well as provide a nice environment for communication and expression. Anthony Eden August 8, 2002 ... to find a new home at Apache • Apache Roller (incubating) – Incubation period: June 2005 - ??? Agenda • Roller history • Roller features • Roller community • Roller internals: backend • Roller internals: frontend • Customizing Roller • Roller futures Roller features: standard blog stuff • Individual and group blogs • Hierarchical categories • Comments, trackbacks and referrers • File-upload and Podcasting support • User editable page templates • RSS and Atom feeds • Blog client support (Blogger/MetaWeblog API) • Built-in search engine Multiple blogs per user Multiple users per blog Blog client support • XML-RPC based Blogger and MetaWeblog API • Lots of blog clients work with Roller, for example: ecto http://ecto.kung-foo.tv For Mac OSX and Windows Roller 3.0: What's new • Big new release, 3 months in dev -

The Jakarta Struts Cookbook Is an Amazing Collection of Code

Jakarta Struts Cookbook By Bill Siggelkow Publisher: O'Reilly Pub Date: February 2005 ISBN: 0-596-00771-X Pages: 526 Table of • Contents • Index • Reviews • Examples The Jakarta Struts Cookbook is an amazing collection of code solutions to Reader common--and uncommon--problems encountered when building web • Reviews applications with the Struts Framework. With solutions to real-world • Errata problems just a few page flips away, this quick, look-up reference is • Academic perfect for independent developers, large development teams, and everyone in between who wishes to use the Struts Framework to its fullest potential. Jakarta Struts Cookbook By Bill Siggelkow Publisher: O'Reilly Pub Date: February 2005 ISBN: 0-596-00771-X Pages: 526 Table of • Contents • Index • Reviews • Examples Reader • Reviews • Errata • Academic Copyright Preface Audience Scope and Organization Assumptions This Book Makes Conventions Used in This Book Using Code Examples Comments and Questions Safari Enabled Acknowledgments Chapter 1. Getting Started: Enabling Struts Development Introduction Recipe 1.1. Downloading Struts Recipe 1.2. Deploying the Struts Example Application Recipe 1.3. Migrating from Struts 1.0 to Struts 1.1 Recipe 1.4. Upgrading from Struts 1.1 to Struts 1.2 Recipe 1.5. Converting JSP Applications to Struts Recipe 1.6. Managing Struts Configuration Files Recipe 1.7. Using Ant to Build and Deploy Recipe 1.8. Generating Struts Configuration Files Using XDoclet Chapter 2. Configuring Struts Applications Introduction Recipe 2.1. Using Plug-ins for Application Initialization Recipe 2.2. Eliminating Tag Library Declarations Recipe 2.3. Using Constants on JSPs Recipe 2.4. Using Multiple Struts Configuration Files Recipe 2.5. -

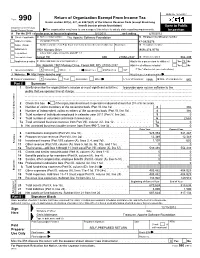

Return of Organization Exempt from Income

OMB No. 1545-0047 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax Form 990 Under section 501(c), 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except black lung benefit trust or private foundation) Open to Public Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service The organization may have to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements. Inspection A For the 2011 calendar year, or tax year beginning 5/1/2011 , and ending 4/30/2012 B Check if applicable: C Name of organization The Apache Software Foundation D Employer identification number Address change Doing Business As 47-0825376 Name change Number and street (or P.O. box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite E Telephone number Initial return 1901 Munsey Drive (909) 374-9776 Terminated City or town, state or country, and ZIP + 4 Amended return Forest Hill MD 21050-2747 G Gross receipts $ 554,439 Application pending F Name and address of principal officer: H(a) Is this a group return for affiliates? Yes X No Jim Jagielski 1901 Munsey Drive, Forest Hill, MD 21050-2747 H(b) Are all affiliates included? Yes No I Tax-exempt status: X 501(c)(3) 501(c) ( ) (insert no.) 4947(a)(1) or 527 If "No," attach a list. (see instructions) J Website: http://www.apache.org/ H(c) Group exemption number K Form of organization: X Corporation Trust Association Other L Year of formation: 1999 M State of legal domicile: MD Part I Summary 1 Briefly describe the organization's mission or most significant activities: to provide open source software to the public that we sponsor free of charge 2 Check this box if the organization discontinued its operations or disposed of more than 25% of its net assets. -

Kony Mobilefabric Integration Service - Manual Upgrade Version 1.3

Kony MobileFabricTM Integration Service - Manual Upgrade Release 7.2 Document Relevance and Accuracy This document is considered relevant to the Release stated on this title page and the document version stated on the Revision History page. Remember to always view and download the latest document version relevant to the software release you are using. © 2016 by Kony, Inc. All rights reserved 1 of 130 Kony MobileFabric Integration Service - Manual Upgrade Version 1.3 Copyright © 2013 by Kony, Inc. All rights reserved. October, 2016 This document contains information proprietary to Kony, Inc., is bound by the Kony license agreements and may not be used except in the context of understanding the use and methods of Kony Inc, software without prior, express, written permission. Kony, Empowering Everywhere, Kony MobileFabric, Kony Nitro, and Kony Visualizer are trademarks of Kony, Inc. Microsoft, the Microsoft logo, Internet Explorer, Windows, and Windows Vista are registered trademarks of Microsoft Corporation. Apple, the Apple logo, iTunes, iPhone, iPad, OS X, Objective-C, Safari, Apple Pay, Apple Watch and Xcode are trademarks or registered trademarks of Apple, Inc. Google, the Google logo, Android, and the Android logo are registered trademarks of Google, Inc. Chrome is a trademark of Google, Inc. BlackBerry, PlayBook, Research in Motion, and RIM are registered trademarks of BlackBerry. All other terms, trademarks, or service marks mentioned in this document have been capitalized and are to be considered the property of their respective owners. © 2016 by Kony, Inc. All rights reserved 2 of 130 Kony MobileFabric Integration Service - Manual Upgrade Version 1.3 Revision History Date Document Description of Modifications/Release Version 10/24/2016 1.3 Document updated for release 7.2 07/20/2016 1.2 Document updated for release 7.1 06/10/2016 1.1 Appended new section Upgrading Tomcat from 5.0.x to 7.0.x. -

Apache Cocoon 2

Apache Cocoon 2 Motivación, Introducción y Explicación Saúl Zárrate Cárdenas Apache Cocoon 2: Motivación, Introducción y Explicación por Saúl Zárrate Cárdenas Este documento se cede al dominio público. Historial de revisiones Revisión 0.0 6 de Mayo de 2002 Revisado por: szc Creación Historial de revisiones Revisión 0.1 5 de Junio de 2002 Revisado por: jidl Correcciones de ortografía y marcado Historial de revisiones Revisión 0.2 17 de Julio de 2002 Revisado por: szc Adición de formato de reunión semanal como apéndice y organización de directorios para las imagenes y los fuentes Historial de revisiones Revisión 0.3 31 de agosto de 2002 Revisado por: fjfs Cambio de formato de imágenes a png y correcciones ortográficas Revisión 1.0 18 de Octubre de 2002 Revisado por: jid Conversión a xml, correccion de errores menores de marcado Tabla de contenidos 1. ¿Por qué Cocoon? ..................................................................................................................................1 1.1. Motivación ..................................................................................................................................1 1.2. Entornos de publicación web (Web Publishing Framework) ......................................................2 2. Cocoon ....................................................................................................................................................3 2.1. ¿Qué es Cocoon?.........................................................................................................................3