Embodiment. Games and Culture, 3 (3-4), Pp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347 PlayStation 3 Atlus 3D Dot Game Heroes PS3 $16.00 52 722674110402 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Ace Combat: Assault Horizon PS3 $21.00 2 Other 853490002678 PlayStation 3 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars PS3 $14.00 37 Publishers 014633098587 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Alice: Madness Returns PS3 $16.50 60 Aliens Colonial Marines 010086690682 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ (Portuguese) PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines (Spanish) 010086690675 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines Collector's 010086690637 PlayStation 3 Sega $76.00 9 Edition PS3 010086690170 PlayStation 3 Sega Aliens Colonial Marines PS3 $50.00 92 010086690194 PlayStation 3 Sega Alpha Protocol PS3 $14.00 14 047875843479 PlayStation 3 Activision Amazing Spider-Man PS3 $39.00 100+ 010086690545 PlayStation 3 Sega Anarchy Reigns PS3 $24.00 100+ 722674110525 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Armored Core V PS3 $23.00 100+ 014633157147 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Army of Two: The 40th Day PS3 $16.00 61 008888345343 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed II PS3 $15.00 100+ Assassin's Creed III Limited Edition 008888397717 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft $116.00 4 PS3 008888347231 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III PS3 $47.50 100+ 008888343394 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed PS3 $14.00 100+ 008888346258 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood PS3 $16.00 100+ 008888356844 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Revelations PS3 $22.50 100+ 013388340446 PlayStation 3 Capcom Asura's Wrath PS3 $16.00 55 008888345435 -

Xbox 360 Total Size (GB) 0 # of Items 0

Done In this Category Xbox 360 Total Size (GB) 0 # of items 0 "X" Title Date Added 0 Day Attack on Earth July--2012 0-D Beat Drop July--2012 1942 Joint Strike July--2012 3 on 3 NHL Arcade July--2012 3D Ultra Mini Golf July--2012 3D Ultra Mini Golf Adventures 2 July--2012 50 Cent: Blood on the Sand July--2012 A World of Keflings July--2012 Ace Combat 6: Fires of Liberation July--2012 Ace Combat: Assault Horizon July--2012 Aces of Galaxy Aug--2012 Adidas miCoach (2 Discs) Aug--2012 Adrenaline Misfits Aug--2012 Aegis Wings Aug--2012 Afro Samurai July--2012 After Burner: Climax Aug--2012 Age of Booty Aug--2012 Air Conflicts: Pacific Carriers Oct--2012 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars Dec--2012 Akai Katana July--2012 Alan Wake July--2012 Alan Wake's American Nightmare Aug--2012 Alice Madness Returns July--2012 Alien Breed 1: Evolution Aug--2012 Alien Breed 2: Assault Aug--2012 Alien Breed 3: Descent Aug--2012 Alien Hominid Sept--2012 Alien vs. Predator Aug--2012 Aliens: Colonial Marines Feb--2013 All Zombies Must Die Sept--2012 Alone in the Dark Aug--2012 Alpha Protocol July--2012 Altered Beast Sept--2012 Alvin and the Chipmunks: Chipwrecked July--2012 America's Army: True Soldiers Aug--2012 Amped 3 Oct--2012 Amy Sept--2012 Anarchy Reigns July--2012 Ancients of Ooga Sept--2012 Angry Birds Trilogy Sept--2012 Anomaly Warzone Earth Oct--2012 Apache: Air Assault July--2012 Apples to Apples Oct--2012 Aqua Oct--2012 Arcana Heart 3 July--2012 Arcania Gothica July--2012 Are You Smarter that a 5th Grader July--2012 Arkadian Warriors Oct--2012 Arkanoid Live -

Star Wars Video Game Planets

Terrestrial Planets Appearing in Star Wars Video Games In order of release. By LCM Mirei Seppen 1. Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back (1982) Outer Rim Hoth 2. Star Wars (1983) No Terrestrial Planets 3. Star Wars: Jedi Arena (1983) No Terrestrial Planets 4. Star Wars: Return of the Jedi: Death Star Battle (1983) No Terrestrial Planets 5. Star Wars: Return of the Jedi (1984) Outer Rim Forest Moon of Endor 6. Death Star Interceptor (1985) No Terrestrial Planets 7. Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back (1985) Outer Rim Hoth 8. Star Wars (1987) Mid Rim Iskalon Outer Rim Hoth (Called 'Tina') Kessel Tatooine Yavin 4 9. Ewoks and the Dandelion Warriors (1987) Outer Rim Forest Moon of Endor 10. Star Wars Droids (1988) Outer Rim Aaron 11. Star Wars (1991) Outer Rim Tatooine Yavin 4 12. Star Wars: Attack on the Death Star (1991) No Terrestrial Planets 13. Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back (1992) Outer Rim Bespin Dagobah Hoth 14. Super Star Wars 1 (1992) Outer Rim Tatooine Yavin 4 15. Star Wars: X-Wing (1993) No Terrestrial Planets 16. Star Wars Chess (1993) No Terrestrial Planets 17. Star Wars Arcade (1993) No Terrestrial Planets 18. Star Wars: Rebel Assault 1 (1993) Outer Rim Hoth Kolaador Tatooine Yavin 4 19. Super Star Wars 2: The Empire Strikes Back (1993) Outer Rim Bespin Dagobah Hoth 20. Super Star Wars 3: Return of the Jedi (1994) Outer Rim Forest Moon of Endor Tatooine 21. Star Wars: TIE Fighter (1994) No Terrestrial Planets 22. Star Wars: Dark Forces 1 (1995) Core Cal-Seti Coruscant Hutt Space Nar Shaddaa Mid Rim Anteevy Danuta Gromas 16 Talay Outer Rim Anoat Fest Wildspace Orinackra 23. -

Acquiring Literacy: Techne, Video Games and Composition Pedagogy

ACQUIRING LITERACY: TECHNE, VIDEO GAMES AND COMPOSITION PEDAGOGY James Robert Schirmer A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2008 Committee: Kristine L. Blair, Advisor Lynda D. Dixon Graduate Faculty Representative Richard C. Gebhardt Gary Heba © 2008 James R. Schirmer All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Kristine L. Blair, Advisor Recent work within composition studies calls for an expansion of the idea of composition itself, an increasing advocacy of approaches that allow and encourage students to greater exploration and more “play.” Such advocacy comes coupled with an acknowledgement of technology as an increasingly influential factor in the lives of students. But without a more thorough understanding of technology and how it is manifest in society, any technological incorporation is almost certain to fail. As technology advances along with society, it is of great importance that we not only keep up but, in fact, reflect on process and progress, much as we encourage students to do in composition courses. This document represents an exercise in such reflection, recognizing past and present understandings of the relationship between technology and society. I thus survey past perspectives on the relationship between techne, phronesis, praxis and ethos with an eye toward how such associative states might evolve. Placing these ideas within the context of video games, I seek applicable explanation of how techne functions in a current, popular technology. In essence, it is an analysis of video games as a techno-pedagogical manifestation of techne. With techne as historical foundation and video games as current literacy practice, both serve to improve approaches to teaching composition. -

Becoming Human? Ableism and Control in <Em>Detroit: Become

Human-Machine Communication Volume 2, 2021 https://doi.org/10.30658/hmc.2.7 Becoming Human? Ableism and Control in Detroit: Become Human and the Implications for Human- Machine Communication Marco Dehnert1 and Rebecca B. Leach1 1 The Hugh Downs School of Human Communication, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA Abstract In human-machine communication (HMC), machines are communicative subjects in the creation of meaning. The Computers are Social Actors and constructivist approaches to HMC postulate that humans communicate with machines as if they were people. From this perspective, communication is understood as heavily scripted where humans mind- lessly apply human-to-human scripts in HMC. We argue that a critical approach to com- munication scripts reveals how humans may rely on ableism as a means of sense-making in their relationships with machines. Using the choose-your-own-adventure game Detroit: Become Human as a case study, we demonstrate (a) how ableist communication scripts ren- der machines as both less-than-human and superhuman and (b) how such scripts manifest in control and cyborg anxiety. We conclude with theoretical and design implications for rescripting ableist communication scripts. Keywords: human-machine communication, ableism, control, cyborg anxiety, Computers are Social Actors (CASA) Introduction Human-Machine Communication (HMC) refers to both a new area of research and concept within communication, defined as “the creation of meaning among humans and machines” (Guzman, 2018, p. 1; Fortunati & Edwards, 2020). HMC invites a shift in perspective where CONTACT Marco Dehnert • The Hugh Downs School of Human Communication • Arizona State University • P.O. Box 871205 • Tempe, AZ 85287-1205, USA • [email protected] ISSN 2638-602X (print)/ISSN 2638-6038 (online) www.hmcjournal.com Copyright 2021 Authors. -

Subject List - Rbdigital Magazines Subscriptions (March 7, 2017)

Subject List - RBdigital Magazines Subscriptions (March 7, 2017) Architecture Affaires Plus (French) Business Today –Taiwan AD – China Capital France AD - Germany Economist AD - Italia Entrepreneur Magazine Architectural Digest Fast Company Architectural Digest - India Inc. Magazine Architectural Digest - Mexico Kiplinger's Personal Finance Rotman Art & Photography Children Aperture Artist’s Magazine National Geographic Kids ARTnews National Geographic Little Kids Digital Photo Digital Photo Pro Digital SLR Photography Chinese Language Drawing Drawing: The Complete Course AD China Juxtapoz: Art & Culture Magazine Business Today – Taiwan Outdoor Photographer Common Health Magazine – Taiwan Photoshop Creative Cosmopolitan – Hong Kong PleinAir Elegant Beauty - Taiwan Popular Photography Elle - Taiwan Queen’s Quarterly Esquire - Taiwan Shutterbug Evergreen – Taiwan Wallpaper GQ - China Watercolor Artist Global Views Monthly – Taiwan Harper’s Bazaar – Hong Kong Bridal Health 2.0 – Taiwan Marie Claire – Hong Kong Marie Claire - Taiwan Brides Men’s Uno - Taiwan Destination Weddings & Honeymoons Mombaby - Taiwan The Knot Weddings Magazine Next Magazine – Taiwan Martha Stewart Weddings Or - China Rhythms Monthly – Taiwan Business Ryori - Taiwan Scientific American – China Adweek Supertaste – Taiwan 1 Computers Handcrafted Jewelry Handwoven Apple Magazine Interweave Crochet Computer Music Interweave Knits Game informer Jewelry Stringing Gamesmaster Knit & Spin GamesTM Knitscene iPhone Life Knitter MacLife Knitting & Crochet from Woman’s Weekly -

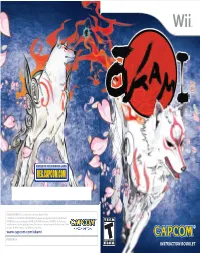

Instruction Booklet

CAPCOM ENTERTAINMENT, INC., 800 Concar Drive, Suite 300, San Mateo, CA 94402 © CAPCOM CO., LTD. 2006, 2008 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Wii development by Ready At Dawn Studios LLC. CAPCOM and the CAPCOM LOGO are registered trademarks of CAPCOM CO., LTD. ŌKAMI is a trademark of CAPCOM CO., LTD. The typefaces included herein are solely developed by DynaComware. The rating icon is a registered trademark of the Entertainment Software Association. All other trademarks are owned by their respective owners. www.capcom.com/okami PRINTED IN USA INSTRUCTION BOOKLET ESRB on Front: 14 x 21 mm OKAMI: Wii Manual Cover - Round 5 Prepared by Eclipse Advertising on: February 28, 2008 PLEASE CAREFULLY READ THE Wii™ OPERATIONS MANUAL COMPLETELY BEFORE USING YOUR Wii HARDWARE SYSTEM, GAME DISC OR ACCESSORY. THIS MANUAL CONTAINS IMPORTANT The Official Seal is your assurance that this product is licensed or manufactured by HEALTH AND SAFETY INFORMATION. Nintendo. Always look for this seal when buying video game systems, accessories, games and related products. IMPORTANT SAFETY INFORMATION: READ THE FOLLOWING WARNINGS BEFORE YOU OR YOUR CHILD PLAY VIDEO GAMES. Dolby, Pro Logic, and the double-D symbol are trademarks of Dolby Laboratories. Manufactured under license from Dolby Laboratories. WARNING – Seizures This game is presented in Dolby Pro Logic II. To play games that carry the Dolby Pro Logic II logo in surround sound, you will need a Dolby Pro Logic II, Dolby Pro Logic or Dolby Pro Logic IIx receiver. These • Some people (about 1 in 4000) may have seizures or blackouts triggered by light flashes or receivers are sold separately. -

4. the Street Fighter Lady

4. The Street Fighter Lady Invisibility and Gender in Game Composition Andy Lemon and Hillegonda C Rietveld Transactions of the Digital Games Research Association December 2019, Vol. 5 No. 1, pp. 107-133. ISSN 2328-9422 © The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution — NonCommercial –NonDerivative 4.0 License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc- nd/ 2.5/). IMAGES: All images appearing in this work are property of the respective copyright owners, and are not released into the Creative Commons. The respective owners reserve all rights ABSTRACT The international success of Japanese game design provides an example of the invisibility of female game composers, as well as of gendered identification in game music production and sound design. Yoko Shimomura, the female composer who produced the iconic soundtrack for the 1991 arcade game, Street Fighter II (Capcom 1991), seems to have been invisible to game developers and music producers, which is partly due to the way in which the game is credited as a team effort. Regardless of their personal gender identity, game composers respond to themed briefs by 107 108 The Street Fighter Lady drawing on transnational musical ideas and gendered stereotypes that resonate with the Global Popular. Game music, as imagined as suitable for hyper-masculine game arcades, seems to draw on a masculinist aesthetic developed in Hollywood compositions. In turn, Street Fighter II’s music and the competitive game culture of arcade fighting games has been interwoven with masculinist music scenes of hip-hop and grime. The discussion of the music of Street Fighter II and the musical versions it inspired, nevertheless highlights that although seemingly simplified gendered stereotypes are reproduced within the game, gender identification itself can be complex within the context of game music composition. -

DETROIT: BECOME HUMAN Author of the Review QUANTIC DREAM: Detroit: Become Human (Playstation 4 Ver- Sion)

BIBLIOGRAPHY The state of Online Gaming – 2018. Market Research. [online]. [2020-03-22]. Available at: <https:// www.limelight.com/resources/white-paper/state-of-online-gaming-2018/>. DETROIT: BECOME HUMAN Author of the review QUANTIC DREAM: Detroit: Become Human (PlayStation 4 ver- sion). [digital game]. Tokyo, San Mateo, CA : Sony Interactive Kateryna Nykytchenko, CSc. Entertainment, 2018. Kyiv National Linguistic University Faculty of Translation Studies Velyka Vasylkivska 73 Łukasz P. Wojciechowski 036 80 Kyiv UKRAINE “I’ve learned a lot since I met you, Connor. Maybe there’s something to this… Maybe [email protected] you really are alive. Maybe you’ll be the ones to make the world a better place… Go ahead, and do what you gotta do.” Hank Anderson, police lieutenant (human) works with his part- ner, Connor (android). Detroit: Become Human by author David Cage is a third-person adventure, similar to the previous games from the studio Quantic Dream1, Heavy Rain2 or Beyond: Two Souls3. And, just like the previous ones, they put a strong emphasis on ramifications of the story, choosing replicas of dialogues or emotional settings, which significantly affect the story and thus create more endings as well. The game follows the implementation of the three rules of robotics by Isaac Asimov that ensure the obedience of androids and their inability to hurt their human owners. The game follows the story of three androids, two of whom are beginning to show signs of faultiness and who strive to cope with their artificial origin, their human needs, wishes and desires. Those androids that ‘wake up’ and evolve beyond their original settings by the CyberLife company are referred to as ‘deviants’. -

Onimusha Soul” for Pcs and Smartphones - Aiming for More Growth in the Online Content Business Through the Multiple Use of Popular Titles

March 9, 2012 Press Release 3-1-3, Uchihiranomachi, Chuo-ku Osaka, 540-0037, Japan Capcom Co., Ltd. Haruhiro Tsujimoto, President and COO (Code No. 9697 Tokyo - Osaka Stock Exchange) Capcom Announces Entry in the Growing Browser Game Market First Title will be “Onimusha Soul” for PCs and Smartphones - Aiming for more growth in the online content business through the multiple use of popular titles - Capcom Co., Ltd. (Capcom) is pleased to announce that the launch date of“Onimusha Soul”, the company’s first browser game, will be June 28, 2012. “Onimusha” is a series of samurai survival action game. Set in the Warring States period of Japan, the games require young swordsmen to advance while slaying enemies and solving mysteries. The first title was “Onimusha”, a game for the “PlayStation®2” that made its debut in 2001 and became the first million seller. Cumulative sales of all “Onimusha” titles were 7.9 million units at the end of December 2011, making this one of Capcom’s most successful series of games. In recent years, the pachislo versions of “Onimusha 3” and “Onimusha: Dawn of Dreams” have also become big hits. “Onimusha Soul” is a Sengoku simulation RPG based on the characters that appear in “Onimusha” series. Each player is a daimyo (feudal lord) of one of the warring states. Players use their powers to achieve the growth of their respective states and train military commanders as they fight with other players. “Onimusha Soul” also allows players to enjoy an original story. The game is easy to play as it offers two unique advantages of browser games. -

Assassins, Gods, and Androids: How Narratives and Game Mechanics Shape Eudaimonic Game Experiences

Media and Communication (ISSN: 2183–2439) 2021, Volume 9, Issue 1, Pages 49–61 DOI: 10.17645/mac.v9i1.3205 Article Assassins, Gods, and Androids: How Narratives and Game Mechanics Shape Eudaimonic Game Experiences Rowan Daneels 1,*, Steven Malliet 1,2, Lieven Geerts 3, Natalie Denayer 1, Michel Walrave 1 and Heidi Vandebosch 1 1 Department of Communication Studies, University of Antwerp, 2000 Antwerp, Belgium; E-Mails: [email protected] (R.D.), [email protected] (S.M.), [email protected] (N.D.), [email protected] (M.W.), [email protected] (H.V.) 2 Inter-Actions Research Unit, LUCA School of Arts, 3600 Genk, Belgium 3 Department of Sociology, University of Antwerp, 2000 Antwerp, Belgium; E-Mail: [email protected] * Corresponding author Submitted: 29 April 2020 | Accepted: 21 June 2020 | Published: 6 January 2021 Abstract Emerging research has suggested that digital games can generate entertainment experiences beyond hedonic enjoyment towards eudaimonic experiences: Being emotionally moved, stimulated to reflect on one’s self or a sense of elevation. Studies in this area have mainly focused on individual game characteristics that elicit singular and static eudaimonic game moments. However, such a focus neglects the interplay of multiple game aspects as well as the dynamic nature of eudai- monic experiences. The current study takes a novel approach to eudaimonic game research by conducting a qualitative game analysis of three games (Assassin’s Creed Odyssey, Detroit: Become Human, and God of War) and taking system- atic notes on game experiences shortly after playing. Results reveal that emotionally moving, reflective, and elevating eudaimonic experiences were elicited when gameplay notes suggested a strong involvement with the game’s narrative and characters (i.e., narrative engagement) and, in some cases, narrative-impacting choices. -

Two Souls and Detroit: Become Human Are Avai- Lable on Steam

PARIS, JUNE 18 2020 HEAVY RAIN, BEYOND: TWO SOULS AND DETROIT: BECOME HUMAN ARE AVAI- LABLE ON STEAM. The Detroit: Community Play Twitch extension and two Stream Packs are also available for free at DetroitCom- munityPlay.com. Quantic Dream’s official eshop launches today preorders for the Detroit: Become Human Collector’s Edition on PC Quantic Dream S.A. announces the availability of its flagship titles on PC, on the online digital distribution service Steam: Heavy RainTM, Beyond: Two SoulsTM and Detroit: Become HumanTM. These three games are available directly on their dedicated Steam pages: • Heavy Rain : https://store.steampowered.com/app/960910/Heavy_Rain • Beyond: Two Souls : https://store.steampowered.com/app/960990/Beyond_Two_Souls • Detroit: Become Human : https://store.steampowered.com/app/1222140/Detroit_Become_Human Heavy RainTM and Beyond: Two SoulsTM are each available for 19,90€. Detroit: Become HumanTM is available for 39,90€. The Detroit: Become Human Collector’s Edition, exclusive to PC, is now available for preorders on the official Quan- tic Dream eshop: https://shop.quanticdream.com/products/detroit-become-human-collectors-edition This limited edition, with only 2500 units available worldwide, contains an exclusive set of 3 pins featuring key icons from the game, as well as a new 27-cm statue of the Android “Kara”, set atop a base illuminated by a halo of LED lights, with integrated movable robot arms. Meanwhile, the Detroit: Community Play experience is also making its debut and is available here: DetroitCommunityPlay.com Announced during the first-ever Quantic Stream on the studio’s official Twitch channel at twitch.com/QuanticDream, this interactive stream extension for the PC version of Detroit: Become HumanTM was designed by the team behind the game and is exclusively available for Twitch.