The Neo-Gramscian Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reaching Beyond the Ivory Tower: a “How To” Manual *

Reaching Beyond the Ivory Tower: A “How To” Manual * Daniel Byman and Matthew Kroenig Security Studies (forthcoming, June 2016) *For helpful comments on earlier versios of this article, the authors would like to thank Michael C. Desch, Rebecca Friedman, Bruce Jentleson, Morgan Kaplan, Marc Lynch, Jeremy Shapiro, and participants in the Program on International Politics, Economics, and Security Speaker Series at the University of Chicago, participants in the Nuclear Studies Research Initiative Launch Conference, Austin, Texas, October 17-19, 2013, and members of a Midwest Political Science Association panel. Particular thanks to two anonymous reviewers and the editors of Security Studies for their helpful comments. 1 Joseph Nye, one of the rare top scholars with experience as a senior policymaker, lamented “the walls surrounding the ivory tower never seemed so high” – a view shared outside the academy and by many academics working on national security.1 Moreover, this problem may only be getting worse: a 2011 survey found that 85 percent of scholars believe the divide between scholars’ and policymakers’ worlds is growing. 2 Explanations range from the busyness of policymakers’ schedules, a disciplinary shift that emphasizes theory and methodology over policy relevance, and generally impenetrable academic prose. These and other explanations have merit, but such recommendations fail to recognize another fundamental issue: even those academic works that avoid these pitfalls rarely shape policy.3 Of course, much academic research is not designed to influence policy in the first place. The primary purpose of academic research is not, nor should it be, to shape policy, but to expand the frontiers of human knowledge. -

Realism in World Politics: the Transatlantic Tradition, Pt. I Professor Matthew Specter Spring 2021 Mondays, 9:30-11:30

Realism in World Politics: The Transatlantic Tradition, Pt. I Professor Matthew Specter Spring 2021 Mondays, 9:30-11:30 Since 1945, three leading traditions have fought for primacy in the theory and practice of US foreign policy: the liberal internationalist, the realist, and the neoconservative. Liberals and realists, so the usual story goes, disagree on the fundamental questions of the relationship of law, morality and power in international politics. Where the liberals are said to be principled multilateralists and earnest supporters of human rights, the realists are said to stick to the austere and amoral calculation of whether actions abroad are in “the national interest.” But the real history is much more complicated. In the postwar era, 1945-1989, US realists and liberal internationalists had much more in common than is usually portrayed. Liberal internationalists were neither consistently liberal nor truly internationalist. They were one face of American primacy in the international system. Realism, sometimes associated with the global balancing of the US, Soviet and Chinese interests by Henry Kissinger, is often thought to have originated in the late 19th century German tradition of Realpolitik, and its master practitioner Bismarck. In this course we explore the myths that have grown up around liberal internationalism, realism, and the relationship between US history and German history that nurtured both sets of ideas. The true story of foreign policy realism is one of a century of transatlantic exchange of ideas, from the US to Germany and back again. The notion that Germany’s modern history followed a deviant path, resulting as it did in the Third Reich, and the US was an exceptional advocate of democracy and fair play in international relations cannot sustain scrutiny. -

John J. Mearsheimer: an Offensive Realist Between Geopolitics and Power

John J. Mearsheimer: an offensive realist between geopolitics and power Peter Toft Department of Political Science, University of Copenhagen, Østerfarimagsgade 5, DK 1019 Copenhagen K, Denmark. E-mail: [email protected] With a number of controversial publications behind him and not least his book, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, John J. Mearsheimer has firmly established himself as one of the leading contributors to the realist tradition in the study of international relations since Kenneth Waltz’s Theory of International Politics. Mearsheimer’s main innovation is his theory of ‘offensive realism’ that seeks to re-formulate Kenneth Waltz’s structural realist theory to explain from a struc- tural point of departure the sheer amount of international aggression, which may be hard to reconcile with Waltz’s more defensive realism. In this article, I focus on whether Mearsheimer succeeds in this endeavour. I argue that, despite certain weaknesses, Mearsheimer’s theoretical and empirical work represents an important addition to Waltz’s theory. Mearsheimer’s workis remarkablyclear and consistent and provides compelling answers to why, tragically, aggressive state strategies are a rational answer to life in the international system. Furthermore, Mearsheimer makes important additions to structural alliance theory and offers new important insights into the role of power and geography in world politics. Journal of International Relations and Development (2005) 8, 381–408. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jird.1800065 Keywords: great power politics; international security; John J. Mearsheimer; offensive realism; realism; security studies Introduction Dangerous security competition will inevitably re-emerge in post-Cold War Europe and Asia.1 International institutions cannot produce peace. -

Dissertation

Critical Realism: An Ethical Approach to Global Politics by Ming-Whey Christine Lee Department of Political Science Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Peter Euben, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Chris Gelpi, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Tim Buthe ___________________________ Rom Coles Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Political Science in the Graduate School of Duke University 2009 i v ABSTRACT Critical Realism: An Ethical Approach to Global Politics by Ming-Whey Christine Lee Department of Political Science Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Peter Euben, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Chris Gelpi, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Tim Buthe ___________________________ Rom Coles An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Political Science in the Graduate School of Duke University 2009 i v Copyright by Ming-Whey Christine Lee 2009 Abstract My dissertation, Critical Realism: An Ethical Approach to Global Politics, investigates two strands of modern political realism and their divergent ethics, politics, and modes of inquiry: the mid- to late 20th century realism of Hans Morgenthau and E.H. Carr and the scientific realism of contemporary International Relations scholarship. Beginning with the latter, I engage in (1) immanent analysis to show how scientific realism fails to meet its own explanatory protocol and (2) genealogy to recover the normative origins of the conceptual and analytical components of scientific realism. Against the backdrop of scientific realism’s empirical and normative shortcomings, I turn to Morgenthau and Carr to appraise what I term their critical realism. -

International Relations in a Changing World: a New Diplomacy? Edward Finn

INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS IN A CHANGING WORLD: A NEW DIPLOMACY? EDWARD FINN Edward Finn is studying Comparative Literature in Latin and French at Princeton University. INTRODUCTION The revolutionary power of technology to change reality forces us to re-examine our understanding of the international political system. On a fundamental level, we must begin with the classic international relations debate between realism and liberalism, well summarised by Stephen Walt.1 The third paradigm of constructivism provides the key for combining aspects of both liberalism and realism into a cohesive prediction for the political future. The erosion of sovereignty goes hand in hand with the burgeoning Information Age’s seemingly unstoppable mechanism for breaking down physical boundaries and the conceptual systems grounded upon them. Classical realism fails because of its fundamental assumption of the traditional sovereignty of the actors in its system. Liberalism cannot adequately quantify the nebulous connection between prosperity and freedom, which it assumes as an inherent truth, in a world with lucrative autocracies like Singapore and China. Instead, we have to accept the transformative power of ideas or, more directly, the technological, social, economic and political changes they bring about. From an American perspective, it is crucial to examine these changes, not only to understand their relevance as they transform the US, but also their effects in our evolving global relationships.Every development in international relations can be linked to some event that happened in the past, but never before has so much changed so quickly at such an expansive global level. In the first section of this article, I will examine the nature of recent technological changes in diplomacy and the larger derivative effects in society, which relate to the future of international politics. -

Grand Theories of European Integration Revisited: Does Identity Politics Shape the Course of European Integration?

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Grand theories of European integration revisited: does identity politics shape the course of European integration? Kuhn, T. DOI 10.1080/13501763.2019.1622588 Publication date 2019 Document Version Final published version Published in Journal of European Public Policy License CC BY-NC-ND Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Kuhn, T. (2019). Grand theories of European integration revisited: does identity politics shape the course of European integration? Journal of European Public Policy, 26(8), 1213-1230. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1622588 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:27 Sep 2021 Journal -

Eu Actorness in the Context of Operation Atalanta

Riikka Hietajärvi MANIFESTATION OF WHAT FOREIGN POLICY – EU ACTORNESS IN THE CONTEXT OF OPERATION ATALANTA Pro gradu -tutkielma Kansainväliset suhteet Kevät 2014 Lapin yliopisto, yhteiskuntatieteiden tiedekunta Työn nimi: Manifestation of what foreign policy – EU actorness in the context of Operation Atalanta Tekijä: Riikka Hietajärvi Koulutusohjelma/oppiaine: Kansainväliset suhteet Työn laji: Pro gradu -työ_x_ Sivulaudaturtyö__ Lisensiaatintyö__ Sivumäärä: 79 Vuosi: 2014 Tiivistelmä: The topic of this master thesis is the European Union foreign and security policy. More detailed, what sort of foreign policy EU is implementing through its military operation EU NAVFOR Atalanta launched to prevent and combat piracy off the coast of Somalia, and which kind of power position it is seeking through it internationally. The theoretical framework creating the structure of the research comes from Hans Morgenthau and his realistic theory, which he introduced more in detail in his book called Politics Among Nations – The Struggle for Power and Peace (1948). In this book, he separates three different policy types based on the state’s foreign policy: policy of imperialism, policy of status quo and policy of prestige. The method of the research is directed content analysis. All the state’s actions, especially the ones that are considered to belong to the area of foreign politics, are somehow after power: they either seek to increase, stabilize or show off it. Consequently, the objective is to recognize w he ther EU is trying to acquire more power, hold on to its present power or mainly just demonstrating its power through Operation Atalanta. Furthermore, embarking upon the identification of the foreign policy type allows us to further see what kind of power distribution EU is seeking in relation to other security actors. -

NEOREALIST and NEO-GRAMSCIAN HEGEMONY in INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS and CONFLICT RESOLUTION DURING the 1990’S

Ekonomik ve Sosyal Ara ştırmalar Dergisi, Güz 2005, 1:88-114 NEOREALIST AND NEO-GRAMSCIAN HEGEMONY IN INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS AND CONFLICT RESOLUTION DURING THE 1990’s Sezai ÖZÇEL İK George Mason University, Institute for Conflict Analysis and Resolution, 3330 N. Washington Blvd. Truland Building, 5th Floor Arlington, VA 22201 [email protected] 1990’LU YILLARDA ULUSLARARASI İLİŞ KİLER VE ÇATI ŞMA ÇÖZÜMÜNDE NEOREAL İZM VE NEO- GRAMS İYAN HEGEMONYA KAVRAMI Abstract The article aims to explain international relations and conflict resolution in combination with the neorealist and neo-Gramscian notions of the hegemony during the 1990s. In the first part, it focuses on neorealist hegemony theories. The Hegemonic Stability Theory (HST) is tested for viability as an explanatory tool of the Cold-War world politics and conflict resolution. Because of the limitations of neorealist hegemony theories, the neo-Gramscian hegemony and related concepts such as historic bloc, passive revolution, civil society and war of position/war of movement are elaborated. Later, the Coxian approach to international relations and world order is explained as a critical theory. Finally, the article attempts to establish a model of structural conflict analysis and resolution. Keywords: Neo-realism, Neo-Gramscian, Hegemony, Conflict Resolution, International Relations Özet Bu makale uluslararası ili şkiler ve çatı şma çözümü kuramlarını neorealist ve neo- Gramsiyan hegemonya kavramlarını çerçevesinde 1990’lı yılları kapsayacak şekilde açıklamayı hedeflemektedir. Birinci -

The 'Great Debates' in International Relations Theory

The ‘Great Debates’ in international relations theory Written by IJ Benneyworth This PDF is auto-generated for reference only. As such, it may contain some conversion errors and/or missing information. For all formal use please refer to the official version on the website, as linked below. The ‘Great Debates’ in international relations theory https://www.e-ir.info/2011/05/20/the-%e2%80%98great-debates%e2%80%99-in-international-relations-theory/ IJ BENNEYWORTH, MAY 20 2011 International relations in the most basic sense have existed since neighbouring tribes started throwing rocks at, or trading with, each other. From the Peloponnesian War, through European poleis to ultimately nation states, Realist trends can be observed before the term existed. Likewise the evolution of Liberalist thinking, from the Enlightenment onwards, expressed itself in calls for a better, more cooperative world before finding practical application – if little success – after The Great War. It was following this conflict that the discipline of International Relations (IR) emerged in 1919. Like any science, theory was IR’s foundation in how it defined itself and viewed the world it attempted to explain, and when contradictory theories emerged clashes inevitably followed. These disputes throughout IR’s short history have come to be known as ‘The Great Debates’, and though disputed it is generally felt there have been four, namely ‘Realism/Liberalism’, ‘Traditionalism/Behaviouralism’, ‘Neorealism/Neoliberalism’ and the most recent ‘Rationalism/Reflectivism’. All have had an effect on IR theory, some greater than others, but each merit analysis of their respective impacts. First we shall briefly explore the historical development of IR theory then critically assess each Debate before concluding. -

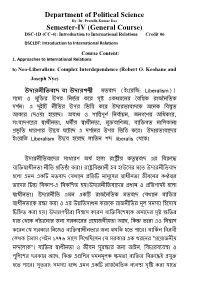

Department of Political Science Semester-IV (General Course)

Department of Political Science By: Dr. Prafulla Kumar Das Semester-IV (General Course) DSC-1D (CC-4): Introduction to International Relations Credit 06 DSC1DT: Introduction to International Relations Course Content: 1. Approaches to International Relations b) Neo-Liberalism: Complex Interdependence (Robert O. Keohane and Joseph Nye) ( : Liberalism)) ও উপ উপ উ ও ও প , , প , , , উ উপ উ Liberalism উ liberalis উ । উ উ - ।উ ও প । উ ও উ । উ প , ও ও প । প ১৭৭৬ " "। ও , ও প , প । প , ও । উ ও উৎ ও প ও প উ উ প , প প ও প প ও উ ও , , ও ও ও , উ , ও , , ও । উ প , ও উ - ৎ , উ প , ও ও । Complex interdependence Complex interdependence in international relations is the idea put forth by Robert Keohane and Joseph Nye. The term "complex interdependence" was claimed by Raymond Leslie Buell in 1925 to describe the new ordering among economies, cultures and races. The very concept was popularized through the work of Richard N. Cooper (1968). With the analytical construct of complex interdependence in their critique of political realism, "Robert Keohane and Joseph Nye go a step further and analyze how international politics is transformed by interdependence" . The theorists recognized that the various and complex transnational connections and interdependencies between states and societies were increasing, while the use of military force and power balancing are decreasing but remain important. In making use of the concept of interdependence, Keohane and Nye also importantly differentiated between interdependence and dependence in analyzing the role of power in politics and the relations between international actors. -

Realism and Peaceful Change Written by Anders Wivel

Realism and Peaceful Change Written by Anders Wivel This PDF is auto-generated for reference only. As such, it may contain some conversion errors and/or missing information. For all formal use please refer to the official version on the website, as linked below. Realism and Peaceful Change https://www.e-ir.info/2018/02/09/realism-and-peaceful-change/ ANDERS WIVEL, FEB 9 2018 This is an excerpt from Realism in Practice: An Appraisal. An E-IR Edited Collection. Available worldwide in paperback on Amazon (UK, USA, Ca, Ger, Fra), in all good book stores, and via a free PDF download. Find out more about E-IR’s range of open access books here. Realism is most often depicted as a tradition or perspective on international relations explaining war and military conflict. This is not without reason as realists have focused on war as a major or even the primary mechanism of change in international relations. Thucydides, in The History of the Peloponnesian War, written in the fifth century BC, and a standard reference in textbook accounts of the realist tradition, found that ‘[t]he growth of the power of Athens, and the alarm which this inspired in Lacedaemon, made war inevitable’ (Thucydides 431 BC, 1.23). This position is echoed in realism up until today. For instance, in his modern classic, aptly entitledWar and Change in World Politics, Robert Gilpin asserts that ‘a precondition for political change lies in a disjuncture between the existing social system and the redistribution of power towards those actors who would benefit most from a change in the system’, and that change in international relations typically equals war (Gilpin 1981, 9). -

The Covid-19 Pandemic, Geopolitics, and International Law

journal of international humanitarian legal studies 11 (2020) 237-248 brill.com/ihls The covid-19 Pandemic, Geopolitics, and International Law David P Fidler Adjunct Senior Fellow, Council on Foreign Relations, USA [email protected] Abstract Balance-of-power politics have shaped how countries, especially the United States and China, have responded to the covid-19 pandemic. The manner in which geopolitics have influenced responses to this outbreak is unprecedented, and the impact has also been felt in the field of international law. This article surveys how geopolitical calcula- tions appeared in global health from the mid-nineteenth century through the end of the Cold War and why such calculations did not, during this period, fundamentally change international health cooperation or the international law used to address health issues. The astonishing changes in global health and international law on health that unfolded during the post-Cold War era happened in a context not characterized by geopolitical machinations. However, the covid-19 pandemic emerged after the bal- ance of power had returned to international relations, and rival great powers have turned this pandemic into a battleground in their competition for power and influence. Keywords balance of power – China – coronavirus – covid-19 – geopolitics – global health – International Health Regulations – international law – pandemic – United States – World Health Organization © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2020 | doi:10.1163/18781527-bja10010 <UN> 238 Fidler 1 Introduction A striking feature of the covid-19 pandemic is how balance-of-power politics have influenced responses to this outbreak.1 The rivalry between the United States and China has intensified because of the pandemic.